Technical & Scientific Research - Juniper Publishers

Abstract

Informal Cross Border Trade (ICBT) is the most fluid sector of trade in Sub-Saharan Africa, and it compares very favorably in efficiency with formal trade in the continent. Reminiscent the rest of the World, women accounts for the highest number of those involved in ICBT in Sub-Saharan region. In East African Community, women accounts for over 60% of informal cross border traders in spite of the efforts to formalize trade. This calls for the study on examination of the drivers of women involvement in informal cross border trade. This paper is based on documented literature to reach a logical conclusion. The scope of the study covers the traditional East African countries; Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania on the borders; Namanga, Isebania and Busia. This paper found out that. Women are driven into informal cross border trade due to two major factors; cultural factors and restrictive measures. The paper concluded that women are involved into cross border trade due to Cultural, social and economic factors. It recommends an empirical study on these areas to understand Women involvement into informal cross border trade in East African Community. Additionally, policy makers should look into possible ways of addressing the barriers to women involvement formal cross border.

Keywords: Women, Drivers, Informal, Border, Trade, Gender, Restrictive, Cultural, Social and Economic

Abbreviations: ICBT: Informal Cross Border Trade, EAC: East African Community; TTC: Trade Transactional Cost

Introduction

African leaders at independence recognized that economic cooperation and integration among African countries was indispensable in the achievement of accelerated transformation and sustained development. In 1980, the Organization of African Union (currently AU) Extraordinary Summit agreed on need to strength intra-African trade through for regional economic blocks. Later in 1991 they would form African Economic Organization under the Lagos Plan of Action which was meant to spearhead formalization of cross border trade within the regional economic blocks [1]. The idea was that a more formal cross border trade among various sub-regional economic communities was to act as a catalyst to improved Gross domestic product and human development Africa [2].

A reality check in Africa since 1980’s however reveals that cross border trade among various sub-regional economic blocks is primarily informal accounting for 60% of intra-trade and 40% GDP (FAO, 2017). Informal cross border trade directly or indirectly escapes from the regulatory framework and often goes unrecorded or incorrectly recorded onto official national statistics of the trading countries [3]. Analysis of several studies reveals that ICBT is quite active even in developed economies and advanced regional economic communities. In Eastern Europe which borders European Union at the Finnish-Russian border in Eastern Karelia, mainly in the towns of Niirala, Tohmaja¨rvi and Sortavala; at the Polish-Belarusian border in Białystok, Kuznica and Brest; at the Polish-Ukrainian border in Przemys´l and Zˇovkva; and at the Ukrainian-Romanian border in Sighetu Marmatiei and Solotvina informal cross border trade has been going on for many years despite the existing regulation and economic data shows that informal trade still accounts for 19% of the GDP [4].

Moreover, in America, there is a strong evidence of informal cross border trade going on between the border of Mexico on the Northern part and United States in South Texas border notably between Ciudad Juarez and El Paso border case. Though no empirical calculation has been made for informality in South Texas, the best estimates suggest that at least 20% of the production end of economic activity (by value) in the region is undertaken via informal means [5]. Scholars have also noted that Informal cross border trade (ICBT) between Entikong (Indonesia) and Tebedu (Malaysia) has existed for hundreds of years before the formation of the concept of state-nations in both countries and corresponding to this, neglecting the inflation rate, the size of informal trading is approximately at 33% from formal trading. It reveals a significant proportion of informal trading in border area, particularly in Entikong in Malaysia with good traded primarily agricultural [6].

Middle East and North Africa States have not been spared either with problems of cross border trade informalities. Although traditionally caricatured as a region with thick economic borders, where the official flow of goods is severely restricted through an array of arbitrary trade barriers, the Middle East and North African border’s regions remain active zones of informal economic exchange. Although there is no region-wide estimate for the size of informal border trade, country-level studies indicate that such trade is both sizeable and significant across the region. A 2013 study on Tunisia found that informal cross-border trade was equivalent to more than half of its official trade with Libya, and more than its entire official trade with Algeria [7].

Similarly in Iran, the size of smuggling in 2007 was estimated to lie in the broad range of 6-25% of total trade [8]. Meanwhile a study for the Algeria-Mali corridor suggests that formal trade pales in comparison to the thriving informal trade across the border [9]. An interesting observation made by United Nations is that for all ICBT activities, women are the dominant players particularly in Africa, Latin America and Asia [10]. Surveys have shown that women constitute between 70 to 80% of people that are engaged in informal cross - border trade [11] dealing in all sorts of merchandize while others offer services. This confirms Hoyman (1987) study which noted that the involvement of women in informal work was nearly doubled compared with men since 9175.

In Sub-Saharan African many women are involved in informal intra-trade cross border trade [10]. Within the Southern Africa Development Cooperation, women comprise about 70 % of those involved in ICBT while in Western and Central Africa nearly 60% of informal traders are women [12]. In Zimbabwe, women constitute 85 percent of the traders [13]. In the Great Lakes region, Titeca and Kimanuka [14] estimate that 85 percent of small-scale traders involved in ICBT in Goma-Gisenyi (DRC-Rwanda) Bukavu-Cyangugu (DRC-Rwanda) Uvira-Gatumba (DRC-Burundi) and Aru/Ariwara-Arua (DRC-Uganda) borders are Women. Among ECOWAS member states ,women have been reported to be the major players in ICBT at 80 % between Sierra-Leone northern border and Guinea at Gbalamuya and with southern border with Liberia at Gendema (Bo-waterside) facilitated by Chata men (Middlemen) who are powerful than the border officials(Vanessa et.al). In Ghana, cross-border trade has a gender dimension in that women are more actively involved in trading across borders than men and are present at all levels of operation with Togo ,Nigeria and Bukina-Faso [15]. Ousmanou [16] study of ICBT among Central African Economic and Monetary Community members concluded that women were the largest participants in this trade various borders such as Ambam, Abang-Minko’o (Camerron-Gabon), at Limbe and Kousseri (Cameroon-Nigeria) and ,Kye’-Ossi (Equitorial Guinea).

In East Africa Community informal cross border trade has a gender dimension and women are slightly more than Men [17]. The EAC (2019), survey noted that a proportion of informal cross border traders among traditional founders of the block (Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania) are women in spite of the efforts to promote formalization of trade in the region [17].

Informal trade is an integral part and unrecognized component of Africa’s economy which has persisted despite the effort to graft it into formal economy globally [18]. The World Bank recommends that all intra-trade should be formalized for states to realize the existing benefits. However, this is not the case in EAC where informal cross border trade accounts for 40% of intra-trade share with women being the majority participants at more than 80% [19]. The dangers of ICBT to states includes the fact that at times the informal imports present unfair competition to domestic industries, products traded informally are often counterfeit goods sold at lower prices, not subject to import taxes, and simply cheaper than locally manufactured equivalents and also represents a significant revenue loss for governments [12]. Many studies focus on impacts of cross border trade in RECs, others on nature and trends [20] limited analysis have focused on drivers of women into informal cross border trade. This paper therefore intends to examine drivers of women into informal cross border trade between Kenya and her neighboring partner states of Uganda and Tanzania).

Conceptualization of Informal Cross Border Trade

The term informal trade first appeared in a report of the International Labour Organization (1972) and then in an article by Hart [21], an anthropologist who had worked in Ghana and Kenya [22]. Attempts at defining ICBT have not been universally conclusive. However, much thinking has gone into this and not only in the context of Africa but a definition that could be universally applied. Lesser and Moisé-Leeman study [23], construe’s ICBT “as trade in legitimately produced goods and services, which circumvents the regulatory framework set by the government and as such avoiding certain tax and regulatory burdens” [23]. Comparably, Afrika and Ajumbo [12] could not agree less with Lesser and Moisé’s understanding of ICBT by referring to it as “trade in processed or non-processed merchandise which may be legal imports or exports on one side of the border and illicit on the other side and vice-versa, on the account of not having been subjected to statutory border formalities such as customs clearance” [12].

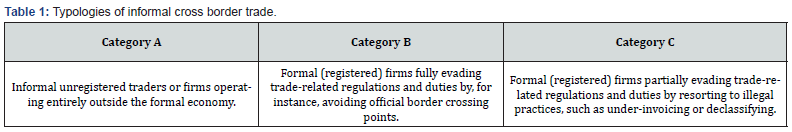

Schneider [24] categorized informal cross border trade in three broader areas that can be practiced by formal or informal traders and companies with varied practices as highlighted in Table 1 This Categorization is helpful in measurability of informal cross border trade. Majority of women informal cross border traders operates under category A, which primarily evades payments of charges, duties, other related transactional costs and regulations prescribed by the government and on account of measurability it is the easiest. Informal cross border trades are.

Informal Cross Border Trade Trends Between Kenya and Her Neibouring Countries of Uganda and Tanzania.

The East African Community (EAC) was founded in 1967, dissolved in 1977, and revived with the Treaty for the Establishment of the East African Community signed in 1999 by Kenya, Uganda and United Republic of Tanzania. Burundi and Rwanda became members in 2007 while South Sudan gained accession in April 2016. Known to be the best performing REC in Africa with 22% intra-trade share, EAC is home to more than 177 million citizens, of which over 22% is urban population, with a land area of 2.5 million square kilometers and a combined Gross Domestic Product of US$ 193 billion (EAC Statistics for 2019). Kenya’s GDP (US$70.5) accounts for almost half of the EAC GDP in 2019, followed by Tanzania (US$47.4) and Uganda (US$25.5). Additionally, the share for intra-trade between these Countries accounts for more than half the total trade shares in the sub-region. In 2018, East African Community trade and investment report showed that the total share of export from Kenya to Uganda accounted 39.5%, while Tanzania was at 19.3%.Similary exports from Uganda to Kenya accounted to 46% while from Tanzania stood at 48% of the total share of export (EAC 2018).

Despite impressive data on the share of export between Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania respectively, a significant proportion of cross border trade is conducted informally at about 40% of the total intra-trade share with women being the major players at around 80% (EAC, 2019). Survey from Uganda in 2018 survey showed that Kenya was Uganda’s main source of informal imports representing 41.6% with goods worth US$ 25.0 million. Similarly, this survey showed some gender dimensions with women being the majority. Meanwhile Busia border was the leading entry point for informal imports with an import bill of US$15.7 million (26.2 percent) with Industrial products/goods like building materials, petroleum products, utensils, beer, and soft drinks constituting the largest informal import from Kenya to Uganda [25]. Correspondingly, Uganda’s Informal export to Kenya represented 27.4 percent of the total informal exports amounting to US$ 150 million in 2018 which seen a marginal reduction from 36.3% in the previous year. Main exported commodities on an informal basis included; Shoes, Clothes (New & used),Fish, Beans ,Maize flour, Sandals, Hair synthetic, Eggs, Bread, Bags, Sorghum grains, Cattle, Polythene bags, Bed sheets, Mattresses, Tomatoes, Goats, Fruits and Suitcases (EAC,2018).

According to Kenya National Bureau of Statistics of 2011(The most recent report on informal cross border trade by Kenya Government), compared to other neighboring countries, Kenya’s total unrecorded informal export trade with Tanzania was highest, valued at Ksh 1,447.4 million, during the second quarter of 2011. The informal exports and informal imports were Ksh 909.8 million and 537.5 million, respectively, in the same period. The industrial products worth Ksh 825.9 million dominated Kenya’s informal exports to Tanzania. The agricultural and industrial import products from Tanzania were valued at Ksh 262.6 million and Ksh 250.3 million, respectively, during the second quarter of 2011. The leading agricultural informal exports to Tanzania were Irish potatoes and coconuts. Under industrial products category, the main exported commodities to Tanzania comprised building materials (paints, iron sheets, cement, steel bars, ceiling boards and nails), utensils, beer, soft drinks, margarine, wire wares, plastic buckets and basins and bread. Dry maize, onions, rice, fruits (oranges) and fish were the main imported agricultural products from Tanzania, under unrecorded informal trade during the second quarter of 2011. The leading imported industrial products from Tanzania were artificial flowers, gas, maize flour and articles of apparel and clothing accessories.

Kenya National Bureau of Statistics pointed out that ICBT propelled by women was highest in Isebania, Namanga and Taveta with informal export amounting to 778 million, 17.3million and 88.4 million accounting to 52%, 1.6% and 6% share of export from Kenya to Tanzania. Similarly, value of imports from Tanzania to Kenya was at 283.2 million - Namanga border, 116.3 million-Taveta Border and 44.4 million-Isebania accounting for 22%, 9% and 3.5% total share of imports [26]. Gor [27], also noted that Kenya’s informal imports from Tanzania are mainly agricultural food commodities and Fish. Maize is the leading item followed by beans, fish and rice. Others include yams, carrots, tomatoes, cassava, cabbages, cow peas, sugar, rice, bananas, millet, maize meal and groundnuts. Kenya’s agricultural food exports to Tanzania include wheat flour, bread, root crops, sugar, rice, bananas, maize meal, milk and coffee. Most agricultural commodities traded are largely influenced by the food items grown around the border and in the neighboring areas.

Most participants in informal cross border trade between Kenya/Uganda and Kenya/Tanzania are individual traders, a large proportion of which are women and micro, small and medium sized enterprises [23]. Women involvement in ICBT consequently has a great contribution in deepening regional trade and integration. Perhaps it will be important to find out what drives these women into informal cross border trade despite adoption of customs union and common market by members of EAC which were meant to ease formalization of trade.

Scope of the Study

This study primarily focused on examining women in informal cross border trade of the traditional East African Community. The borders under the study are; Isebania and Namanga on kenya-Tanzania borders and Busia on Kenya-Uganda border.

Methodology

This is purely desk research which used the already documented literature analytically to arrive at the logical conclusion on the subject under the study.

and Tanzania

Drivers of women involvement into ICBT can be classified into two broad categories: Cultural and Socio-Economic factors as explained below

Cultural Factors

There has been a long tradition of movement of people back and forth in the open border area for purchasing daily consumer goods and for business purposes which is a common phenomenon globally [28]. These have been facilitated by common and understandable language, cultural similarities, family relations and trust across the borders. Cultural relations build strong links and cooperation between neighboring nations. Informal trans-border trade often reflects longstanding relationships and indigenous patterns, which often pre-date colonial and postcolonial state boundaries. Cross-border trade is often conducted among people of the same clan or ethnicity group (e.g., Trans-border trade between Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania). The communities spread along the territorial boundaries share a lot in common both culturally and socially. They speak the same or similar languages, they inter-marry and own land on either side of the borders. This alone provides an incentive to these communities to engage in trade to exploit available opportunities on either side of the border [29].

In addition, East African region, trade has thrived due to Kinship ties among the Luos and Kuria in Mara region of Tanzania and the Southern Western Kenya [30,31]. Similalry, Ayot [32] notes that trade along the Kenya -Uganda borders have always thrived due to the surrounding Teso communities. Women have always used these kingship ties to enhance informal cross border trade in EAC [32]. Communities have always resisted any attempt to stifle their cultures. Parallel trade or ICBT can be seen as a form of indigenous resistance to the imposition of colonial borders and metropolitan economic regulations on traditional African economic and social formations [33].

Socio-Economic

Social economic factors are many and divers as discussed below

ICBT and Household Income

Informal cross-border trade supports livelihoods, particularly in remote rural locations. It creates jobs, especially for vulnerable groups such as poor women and unemployed youth, and it contributes to food security in that it largely features raw agricultural products and processed food items (World Bank, 2014). Moreover, the income they earn from these activities is critical to their households, often making the difference, for example, in whether children go to school or not or seek medication. Women’s income from trading activities is of particular importance to households where the spouse in not employed and helps explain the high tolerance for the difficulties that they face in crossing the border [1].

A few studies have shown the ability of ICBT to reduce poverty or empower women. According to Schneider [24], ICBT is a poverty reduction venture because an increase in women’s incomes tends to collate with greater expenditure on children and family welfare, unlike similar increases in the incomes of men. Furthermore, Gerald and Rauch [34] observed that ICBT provides specific opportunities for the empowerment of women through the development of informal and formal sector retail markets, the creation of employment opportunities and provide access to some capital thereby creating an opportunity to alleviate poverty. These traders play a key role in food security, bringing basic food products from areas where they are relatively cheap to areas where they are in short supply.

Regulatory Barriers

African cross border traders, especially women, are constrained by such issues as high duty and tax levels, poor border facilities, cumbersome bureaucracies, lengthy clearance processes, weak governance at the border, lack of understanding of the rules, and corruption. Moreover, cross-border traders face other difficulties before even reaching the borders, such as problems with registering their businesses, securing capital and assets, or increasing the quality and quantity of the products they trade. According to Limao and Venables (2001), Trade Transaction Costs (TTCs) in intra-Sub-Saharan Africa trade are substantially higher and more obstructive than those for other African countries due to the relatively low efficiency of customs procedures and institutions in the region. In fact, perishable agricultural and food products are often subject to additional trade-related procedures which are meant to ensure compliance with sanitary and phyto-sanitary requirements.

Lesser C and Moisé-Leeman E [23] observed that on average, Africa has the longest customs delays in the world. Consignments commonly experience substantial and unpredictable delays of 30 to 40 days before release from customs control. Not only are the delays long, but they are also costly. Recent OECD in 2003 work also emphasizes that the barriers to formal South-South trade, including intra-regional trade in Sub-Saharan Africa, are often more important than barriers to North- South or North-North (formal) trade (Kowalski and Shepherd, 2006). These lengthy and cumbersome processes lead to a considerable increase in border process fees and clearance times per consignment, hence leading to informal cross border trade.

Additionally, another factor that can further facilitate informal cross-border trade is the weak enforcement of laws and regulations, the arbitrary application of trade-related regulations and the pervasiveness of corruption at borders [35]. On the other hand, the arbitrary application of regulations and the quasi-automatic requirement of facilitation payments bribes (Kitu Kidogo) at some border points might incite some traders to engage in illegal practices such as under- invoicing and/or pass through other, sometimes unofficial routes and crossings, to avoid having to disburse such payments. It has been observed that corruption is still one of the most important obstacles to doing (formal) business on the continent and East Africa in particular [36].

Beyond the costs they bear, regulatory requirements are sometimes also unknown or unclear to traders. In recent surveys and workshops conducted in the East African Community (EAC) and for example, traders have consistently cited lack of information on regulatory requirements (e.g., quality standards, customs documents and procedures and certificates of origin and conformity) as a key constraint towards formal cross-border trade in the region. A recent EAC report for example notes that the lack of information on regulation compels many traders to engage in unrecorded trade across the border (EAC, 2019).

Gender Inequalities

The female predominance in informal cross-border trade is often attributed to women’s time and mobility constraints, as well as to their limited access to productive resources and support systems, making such trade one of the few options available to them to earn a living [37]. Women who are informal traders typically have no or limited primary education and rarely have had previous formal jobs. If married, they seldom receive contributions from their husbands to start business operations. Similarly, gender norms restricting women’s mobility, access, and control over resources and decision-making within the household impact how women participate in ICBT.

In spite of the significant role women play in the economy, they grapple with many disadvantages including limited access to land, financial services, information, technology, and training services, all as a result of gender disparities in rights, the gender-differentiated impacts of neo-liberal restructuring, and the erosion of kin-based support networks through migration [38]. Insufficient attention to gender analysis has meant that women’s contributions and concerns remain too often ignored in financial markets and institutions, trade systems, labour markets, economics as an academic discipline, economic and social infrastructure, taxation and social security systems, as well as in families and households. These factors are enables for women involvement into ICBT [39-45].

Summary of Findings

The paper founded that women are the major players involved into informal cross border trade. Women are driven into informal cross border trade due to cultural reasons like historically shared border areas, common language and kinship ties which have deepen trade links. It is noted also that the desire to reduce poverty and improve household income to support livelihood e.g., food, education and medication have pushed women into informal cross border trade. Moreover, restrictive measures such issues as high duty and tax levels, poor border facilities, cumbersome bureaucracies, lengthy clearance processes, weak governance at the border, lack of understanding of the rules, and corruption facilitate women participation into ICBT. Finally, gender inequality notably lacks proper education, denial of property rights which can be used to credit, housekeeping roles, inadequate information and restrictive gender norms have limited women’s involvement into formal cross border trade [46-50].

Conclusion and Recommendations

Women have become so synonymous with informal cross border trade. This paper concluded that the drivers of women into informal cross border trade are but not limited to:

• Common and understandable language, cultural ties, family relations and trust across the borders which have built strong trade links;

• Ability of ICBT to help in improving household income aimed at supporting livelihood and alleviating poverty;

• Gender inequality which has denied women socio-economic opportunities thereby pushing them to ICBT and,

• Restrictive measures increase Trade Transactional Cost (TTC).

In conclusion women are involved in cross border trade due to Cultural, social, and economic factors. The paper recommends that an empirical study involving field visit should be done to widely understand Women involvement into informal cross border trade in East African Community. Additionally, policy makers should look into possible ways of addressing the barriers to women involvement formal cross border [51,52].

To Know more about Trends in Technical & Scientific Research

Click here: https://juniperpublishers.com/ttsr/index.php

To Know more about our Juniper Publishers

Click here: https://juniperpublishers.com/index.php

No comments:

Post a Comment