Open Access Journal of Neurology & Neurosurgery

Purpose of the study: The aim of this study was to analyze whether the risk of intracranial hemorrhage, focal neurological deficits and seizure from a cerebral Cavernous Malformations (CCM) changes significantly during pregnancy, delivery and post-partum, and based on the data from this study a recommendation or to give advice for clinical practice regarding maternal and fetal outcomes from the risk of haemorrhagic CCM during pregnancy. Yet there is a paucity of information relating to this in the medical literature. Basic procedures: We searched for publications on cavernous malformation in pregnancy in the MEDLINE database through PubMed. All publications till January 2019 were included in the search, and 16 related articles and 32 case reports were found. Main findings the studies reported that most patients (40%) presented with clinical symptoms of focal neurological deficits such as changes in the motor or sensory function, visual field deficits, ataxia, and hemiparesis. In most patients, the onset of symptoms was during the antepartum period, whereas some patients showed delayed symptoms at 2 weeks to 10 years postpartum. During pregnancy and the peripartum period, conservative management (no surgical intervention) may be used in cases with asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic lesions; however, in cases of severe symptoms occurring early in the course of pregnancy and endangering maternal and fetal life, neurosurgical intervention may be warranted before delivery. Principal conclusion: Most studies have suggested that pregnant women with CCMs can be managed safely even when symptomatic without a significant risk of adverse perinatal outcomes.

Keywords: Cerebral cavernous malformations; Epileptic seizures; Maternal and fetal outcomes

Abbrevations: ICH: Intracranial Hemorrhage; FNDs: Focal Neurological Deficits; MRI: Magnetic Resonance Imaging; GA: gestational age; H: Hemorrhage; S: Seizures; D: Diplopia; FNS: Focal Neurological Deficit; HE: Hemiparesis; CS: Cesarean Section; VD: Vaginal Delivery; TOP: Termination of Pregnancy; CCMs: Cavernous Malformation; N/R: Not Reporting; Term: Term gestation more than 37 weeks

Introduction

Cerebral Cavernous Malformations (CCMs) are focal proliferative hemorrhagic lesions comprising dilated sinusoidal vessels enclosed in a single endothelial layer and embedded in variably thin fibrous adventitia with little or no intervening functional neural parenchyma. These vessels account for 8% to 15% of all cerebrovascular malformations and exhibit distinct features of angioarchitecture and biological mechanisms of genesis and progression; however, they do not exhibit high pressure-flow profile that is characteristic of other intracranial vascular malformations, such as arteriovenous malformations [1]. These lesions can occur throughout the central venous system in the following approximate proportions to the tissue volume 80% supratentorial, 15% posterior fossa, and 5% spinal cord. Further, the lesions can occur in either of the following two forms: the sporadic form characterized by a single lesion and the familial form involving inheritance of multiple lesions in an autosomal dominant pattern with variable penetrance [2]. CMs, with a prevalence of 0.4%-0.5%, have a highly variable presentation ranging from incidentally discovered lesions during evaluation for nonspecific symptoms, such as headache, to symptomatic Intracranial Hemorrhage (ICH) presenting with acute new Focal Neurological Deficits (FNDs) and epileptic seizures [3]. Because of the increasing availability of brain Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI), the rate of CCM diagnosis is increasing without the need of pathological confirmation. This, in turn, has revealed that CCMs were historically more benign than previously thought, particularly compared with their arteriovenous counterparts [4].

In cases of CCM diagnosis in women of childbearing age or in pregnant women, the risk of ICH during pregnancy is substantial and consideration of the delivery mode is crucial because of a high risk of morbidity and/or mortality due to severe hemorrhagic events and progressive neurological deterioration [5]. As the magnitude of the risk of ICH and its rupture rate and outcome events during pregnancy were long uncertain, a few studies attempted to calculate the overall risk of ICH or ICH with intractable seizures in a diverse female population with CCM during pregnancy and delivery or during the 6-week postpartum period; however, the conclusions were not very definitive. The knowledge of these risks is useful for decision making regarding the treatment course to be selected for pregnant women, i.e., conservative management or neurosurgical excision; however, neither of these treatment options has been assessed in a randomized trial, and the use of neurosurgical excision remains controversial and challenging [6]. Therefore, we sought to address these uncertainties by conducting a systematic review of the literature on CCM patients with risks of first ICH or FND during pregnancy. In particular, we aimed to examine the efficacy and safety of management approaches for these lesions during gestation and the implications of the timing of labor and mode of delivery on the maternal and fetal outcomes.

Methods

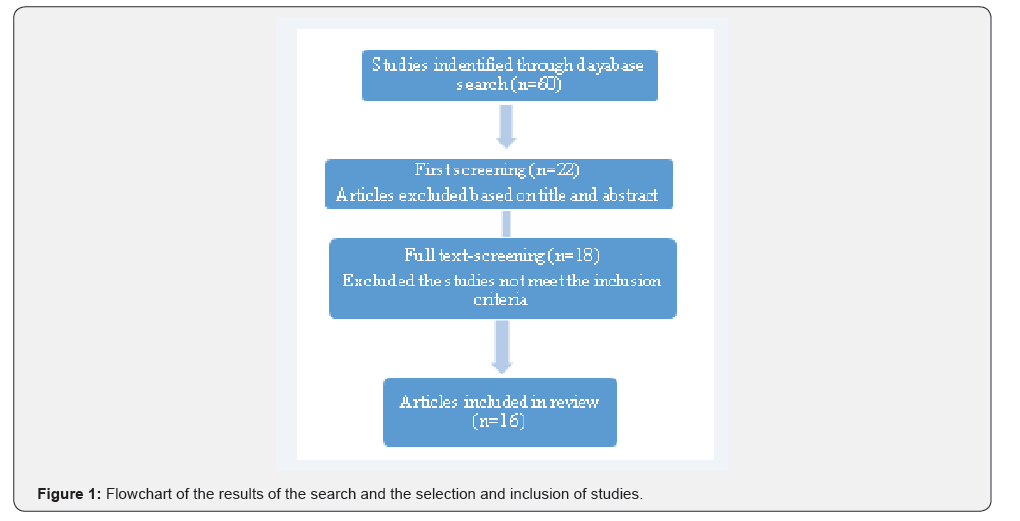

In this systematic review, we searched of the electronic databases Medline (1946 onwards), Central, Embase (1980 onwards) for all articles on this topic published in English. Articles published till January 2019 were considered, using search strategy outlined in Supplement 1, and the following keywords were used for the search pregnancy with cerebral cavernous malformation or cerebral cavernomas in pregnancy or cavernous malformation during pregnancy or puerperium. Inclusion criteria were articles published in English with the primary topic being CCMs complicated with pregnancy and clear descriptions of the clinical presentation, management, and outcomes. Reference lists of the eligible articles were examined to identify other relevant articles. Articles that did not clearly describe the clinical presentation, management, and outcomes were excluded. Initial decisions to include or exclude studies were made based on the study title. Subsequent decisions were made based on the abstract and full-body text.

Results and Discussion

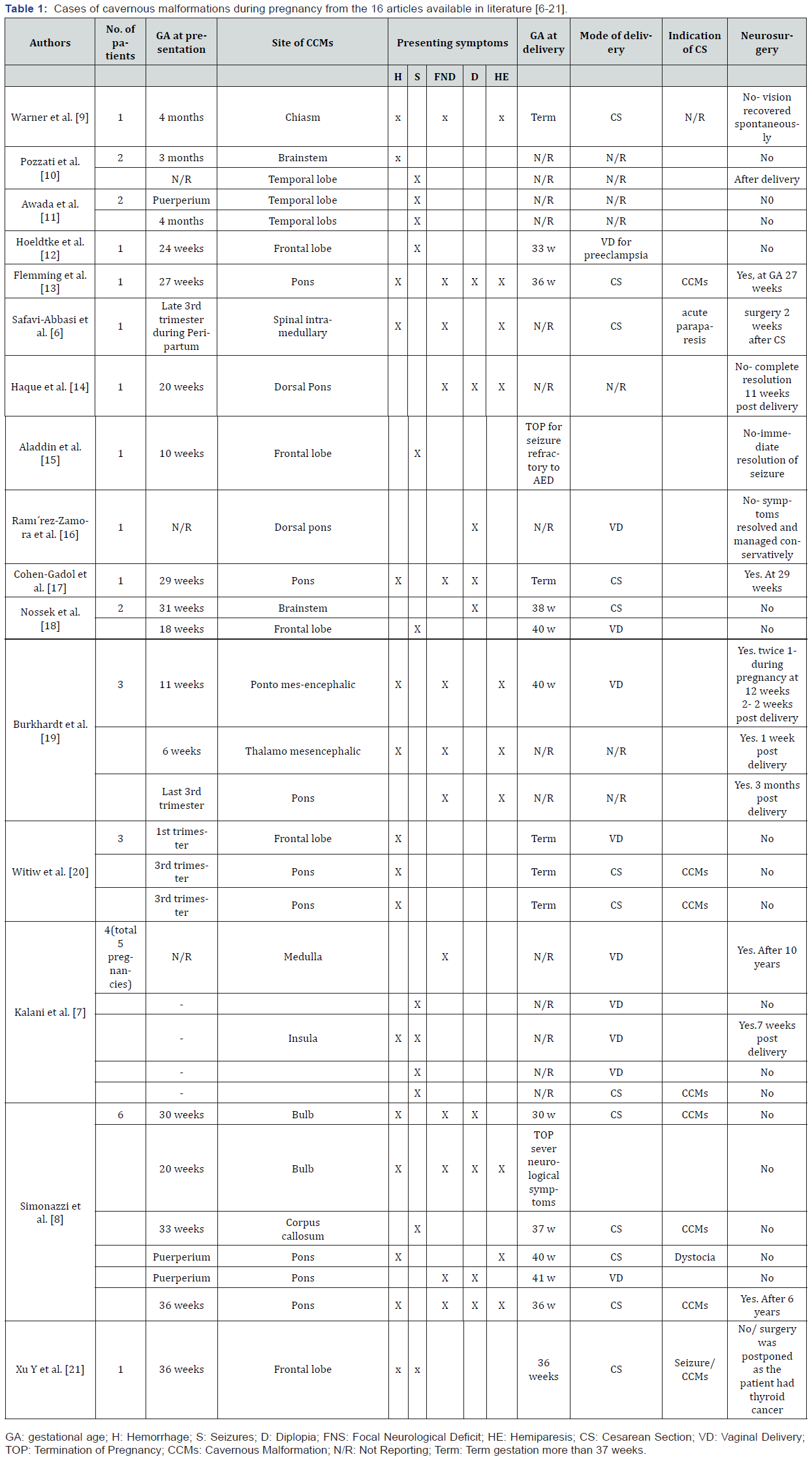

The systemic search revealed 60 related publications. After primary screening based on the inclusion criteria, 22 articles based on title/abstract assessment and 18based on full-text assessment were found eligible. Of these articles, 18 were selected, resulting in the inclusion of 16 articles and 32 single case reports published until January 2019. Of the 16 articles, 14 included only one to three cases, one article included five cases, and another included six cases [7,8]. The gestational age at presentations, clinical presentations, and site of CCMs and obstetric outcomes of all the patients reported in the literature are listed in Table 1. The results and discussion may be presented separately, or in one combined section, and may optionally be divided into headed subsections.

clinical presentations of CCMs

According to symptomatic CCMs, during pregnancy or puerperium, assuming an average of 40 weeks of pregnancy and the 6-week postpartum period (puerperium). Out of the 32 patients reported in single case reports, the gestational age at the time of presentation of symptomatic CCMs has been documented for 22 (79%) patients. Of these 22 patients, 16 presented with symptomatic CCM antepartum (second or third trimesters). However, four patients (18%) showed early onset of CCM symptoms in the first trimester (6 weeks of gestation), and two showed delayed onset in the postpartum period.

The 32 patients showed clinical presentations of symptomatic CCMs ranging from acute ICH and onset or worsening of neurological symptoms, including seizures, FNDs, diplopia, and hemiparesis. Notably, 19 of these 32 patients (59%) had ICH. New onset or exacerbation of seizures occurred in 10 patients (31%), and other 10 patients (31%) showed progressive symptoms of hemiparesis. Further, 13 of the 32 patients (40%) exhibited symptoms of FNDs, and other nine patients (28%) had a history of worsening symptomatic hemiparesis with diplopia.

Anatomically, CMs can occur throughout the central nervous system. Of these 32 patients, 15 (47%) had a high propensity of having symptomatic CCMs in the infratentorial area (2 patients had in the brainstem, 10 had in the pons, 1had in the medulla oblongata, and 2 had in the mesencephalic nucleus). Further, the anatomical site of the CCMs in 13 patients (40%) with symptomatic events was the supratentorial area; 7 of these 13 patients had CCMs in the predominant frontal lobe, 3 had in the temporal lobe, 2 had in the supratentorial deep area, and 1had in the insular cortex. One patient (3%) had an intramedullary symptomatic lesion.

Obstetric outcomes of CMMs during pregnancy or puerperium

Information on the obstetrical mode of delivery and/or gestational age at delivery was available only for 24 of the 32 patients (75%). Two of these 24 patients underwent abortion on each 20 weeks of gestation who showed worsening of neurological symptoms due to bulbar CCMs and required therapeutic termination, and the other at 10 weeks of pregnancy for obstetric indication due to severe preeclampsia. Of the 24 patients, nine pregnant women (31%) with symptomatic CCMs had uncomplicated vaginal delivery. The gestational age at the time of delivery was not reported for five of these nine patients, whereas three patients delivered successfully at term gestation and one patient required preterm delivery at 33 weeks because of severe preeclampsia symptoms. Of these nine patients, two underwent neurosurgical intervention after uncomplicated pregnancy and delivery one at 7 weeks postpartum and another at 10 years after her last pregnancy [7]. The first patient had focal seizure episodes involving the right face and arm and underwent successful resection of left insular CCMs after pregnancy at 7 weeks. The second patient underwent surgery for CCMs in the cervical medullary junction because of progressive right-sided weakness 10 years after her last pregnancy [9,10].

Thirteen of the 24 patients (45%) underwent cesarean delivery: six at term gestation, four at preterm gestation, and the gestational age at delivery was unreported for the remaining three cases. Of these 13 patients, eight underwent cesarean delivery because of concerns over CCMs and to reduce the risks of bleeding, one underwent cesarean delivery because of dystocia at 40 weeks, and the indication for cesarean delivery was unreported in the remaining three cases. Of the former eight patients, three underwent cesarean delivery at 36 weeks of gestation because of symptomatic hemorrhages, and one underwent cesarean delivery at 30 weeks of gestation because of severe neurological deficits, with the most common symptom being acute hemorrhage with diplopia.

Neurosurgical resection of CCMs was performed in 4 of the 13 patients who underwent cesarean delivery. Two of these patients had symptomatic CMMs in the pons, one of whom underwent surgery at 27 weeks of gestation and another at 29 weeks of gestation [11-22]. Of the other two patients, one patient with intramedullary CCMs underwent laminectomy 2 weeks after her uneventful cesarean delivery [6], and the other patient with a CCM in the pons underwent neurosurgical resection 6 years postpartum during the fourth haemorrhage [8]. One of these 13 patients had a symptomatic lesion with refractory seizure and was recommended to undergo neurosurgical resection after cesarean delivery at 36 weeks of gestation, but the surgery was not performed as the patient was diagnosed with thyroid cancer. Burkhardt et al. [19]. reported three patients who underwent neurosurgical interventional during and after pregnancy One patient underwent Ponto-mesencephalic CCM resection during 12 weeks of gestation, but 2 weeks after the uncomplicated delivery of her second child, this patient underwent complete resection of this lesion with favorable outcomes [19]. The other two patients underwent CCM resection postpartum: one patient at 1week postpartum and the other at 3 months postpartum. Note that one more patient was reported to have undergone neurosurgical resection postpartum, but her obstetrical data were missing [10].

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first systemic review to highlight whether pregnancy, delivery, and puerperium are associated with an increased risk of symptomatic CCMs and to provide useful information for clinical practice. The incidence of CCMs is extremely rare and only 16 articles and 32 case reports on CCMs are present in the literature. Despite the increasing diagnosis of the de novo formation of CCMs in both sporadic and familial cases, to date, little information is available about their pathogenesis, clinical presentation, imaging characteristics, and related complications, and their pathogenesis and management during pregnancy remain uncertain. Notably, previous studies have emphasized that the increased production of steroid hormones and vascular proliferation during pregnancy are associated with an increased risk of hemorrhage from CCMs Kaya A et al. [23]. demonstrated that progesterone and estrogen receptors are absent in the cerebral vasculature. Therefore, several researchers have speculated that a different pathway mediates the vascular activity of cerebral cavernomas during pregnancy. The development of advanced neuroimaging modalities and techniques for evaluating the expression of immunobiological markers has allowed researchers to implicate the expression of cerebral angiogenic growth factors, such as vascular endothelial growth factor, basic fibroblast growth factor, and transforming growth factor, which are normally dormant in the adult brain tissue, in promoting angiogenesis and proliferation of vascular lesions in CCMs; these same physiological mechanisms are involved in the preparation for and promotion of pregnancy-related vasculogenesis [23] (Figure1).

In clinical practice, the definitive diagnosis for cavernous angiomas involves histopathological confirmation. However, the advancements in neuroimaging modalities has allowed the visualization of the entire cranio-spinal axis using MRI and the consequent diagnosis of CCMs with accuracy, without the need of pathological examination; this technique is especially useful when neurosurgical intervention during pregnancy or puerperium may not be recommended.4 This recommendation was supported by Safavi-Abbasi et al. [6] who reported a 21-year-old woman in whom an intramedullary hemorrhage from a spinal CCM occurred during the peripartum period and therefore spinal cord decompression was performed. The histopathology report of this patient confirmed the diagnostic features of CCMs on T2-weighted images obtained using MRI. Most patients showed clinically symptomatic presentations due to hemorrhagic CCMs during pregnancy, with the onset of symptoms during the antepartum or intrapartum period. Some patients developed delayed symptoms at 2 weeks to 10 years postpartum. Witiw et al. [20] reviewed the pregnancy history data of 186 patients: Of the 49 hemorrhagic events that occurred during childbearing years in pregnant or nonpregnant women, only three hemorrhages occurred during a total of 349 pregnancies (one in the first trimester and two in the third trimester). No hemorrhage occurred during labor or 6 weeks postpartum. Safavi-Abbasi et al. [6] reported a case of hemorrhage that occurred during the peripartum period in a patient with symptomatic spinal intramedullary CCMs; the event occurred 2 weeks postpartum, and she subsequently underwent T9-12 laminectomy for completely resection of the lesion.

Although seizure has been widely reported as the most common neurological manifestation of symptomatic CCMs during pregnancy, Kalani et al. [7] retrospectively reviewed 168 pregnancies among 64 patients and reported only five symptomatic hemorrhages in four patients. The most common symptom was found to be the new onset or exacerbation of seizures, which accounted for 31% of all the symptoms, whereas FNDs accounted for 40% of the symptoms. As expected, the risk of hemorrhage was somewhat higher in patients with brain stem lesions (47%) than in those with supratentorial lesions (40%). Simonazzi et al. [8] reported a case series of six patients, three of whom had a hemorrhagic CCM in the pons and only one of these three underwent neurosurgical resection 6 years postpartum during the fourth hemorrhage. No clear evidence is present in the literature to support or refute prophylactic neurosurgical resection of CCMs for women planning pregnancy or the avoidance of pregnancy on the grounds that it will increase the risk of hemorrhage from CCMs; Kalani et al.[7] reported one patient with a family history of CCMs who had undergone resection of a CCM in the right temporal lobe to control seizure at 8 years of age. At 19 years of age, she had uncomplicated pregnancy and delivered her second child. Although all cases of CCMs should be assessed on individual bases, the occurrence of symptoms in the first trimester does not justify the need for a therapeutic abortion as there is no reported evidence to support such recommendations to reduce the risk of hemorrhage.

Our review revealed that only one patient who had severe symptomatic lesions underwent abortion because of the worsening of neurological symptoms at 20 weeks of gestation. However, the practice of choosing an elective cesarean delivery, with the knowledge that vaginal delivery increases the risk of ICH, to reduce the risks of hemorrhage has been revised. Although limited number of cases of CCMs occurring during pregnancy have been reported, it appears that the risk of hemorrhage from CCMs remains similar antepartum, during delivery or postpartum. In addition, no strong evidence is available showing that the mode of delivery influences the risk of hemorrhage from CCMs; hence, we believe that the decisions regarding the management of labor and mode of delivery should be based on obstetric indications. Witiw et al. [20] reported three cases of symptomatic hemorrhages that occurred during pregnancy. All three women delivered healthy newborns; one via vaginal delivery and the other two via cesarean delivery because of neurological indication (hemifacial weakness, mild hemisensory symptoms, and diplopia) and the risks from vaginal delivery perceived by their obstetricians. Notably, all of these patients recovered well from their hemorrhagic events.

As with any rare condition for which guidelines are lacking, surgical management of pregnant women with asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic lesions will likely increase the risk of developing new symptoms or of aggravating the existing ones, which even if transient, may have devastating consequences (worsening of symptoms). Nevertheless, most reported patients eventually improved with retention of only little disability. Regardless, management must be tailored on a case-by-case basis, based on the neurological or obstetric indications. Neurosurgical resection can be performed postpartum. Burkhardt et al. described three patients with symptomatic lesion of CCMs in the supratentorial deep area during pregnancy [19]. Two of these patients were treated neurosurgically postpartum and one during 6 weeks of gestation. Initially, one of former two patients showed minor clinical symptoms and a stable lesion (left-thalamo-mesencephalic CCM) on MRI, and she underwent surgical resection 1 week after term delivery. The other of the two patients who became symptomatic in her last trimester was treated surgically 3 month after uncomplicated delivery and showed favorable surgical outcomes. In some cases, however, if the symptoms are severe and occur early in the course of pregnancy, an emergency neurosurgical intervention may be required before term for completely removing the symptomatic lesions and avoiding recurrence and rebleeding. Burkhardt et al. reported a similar case of a brainstem (rightponto- mesencephalic) CCM in a patient at 11 weeks of gestation who underwent resection at 12 weeks of gestation, followed by a compete surgical removal of this lesion at 2 weeks postpartum.

There are several limitations to our systematic review should be acknowledged. Only studies that were published in English were included in our study, and thus it may not be representative of all the relevant literature published to date. Second, there are also limitations pertaining to a retrospective study included in our review as some data may not have been validated as well as in planned prospective study. However, it may be hard to define a prospective study considering of the pathological condition is rare and available literature is poor. These are important limitations that must be considered to draw conclusion in this particular subject.

Conclusion

Certainly, it may be difficult to validate or recommend the management of pregnancy in women with symptomatic CCMs mainly because of the lack of obstetrical evidence in the literature due to the rarity of this disease. Regardless, decision making regarding conservative management or neurosurgical intervention of CCMs during pregnancy or postpartum should be based on the time of symptom onset during the course of pregnancy and the lesion location. Most neurosurgeons consider that the risk of hemorrhage remains similar during pregnancy or postpartum and that the need for emergency neurosurgical intervention during pregnancy is rare. No quantitative data are available to support cesarean delivery as the delivery mode of choice in patients with CCMs, and taken together, the results of the previous studies suggest that the mode of delivery should be decided based on obstetric indications. Studies have suggested that the risk of ICH does not particularly increase during pregnancy or postpartum. We generally suggested, based on retrieved data and shared decision between the clinician and patient, that women with CCMs can be managed safely during trial of labor without a significant risk of adverse perinatal outcomes, and consideration needs to be given to planned cesarean section in patients with symptomatic CCMs or when prolonged labor anticipated.

To

Know More About Journal of Open Access Journal Of Neurology & Neurosurgery Please click

on: https://juniperpublishers.com/oajnn/index.php

To Know More About Open Access Journals Please click on: ttps://juniperpublishers.com/index.php

To Know More About Open Access Journals Please click on: ttps://juniperpublishers.com/index.php