Pediatrics & Neonatology - Juniper Publishers

Abstract

Introduction: The number of children presenting with symptoms of mental illness (MI) to emergency departments (ED) increased during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Objective: The objective of this study was to identify changes in ED visits for new onset MI in children compared to children with a pre-existing MI during the COVID-19 pandemic in a paediatric ED.

Methods: A retrospective chart review of children treated for MI in the ED was conducted from March 1,2019 to September 29,2022.

Results: There were 6431visits for mental illness by 5092 patients during the study period. Of them 4084(63.5%) were biological females. During the first two years of the pandemic the percentage of all children presenting with mental illnesses increased significantly compared to the pre pandemic year from 2.04% to 3.34% and 3.5% of all total ED visits and reduced slightly to 2.92% in the third year. New onset MI visits increased from 1.08% in the pre pandemic year to 1.63%, 1.65 % and1.65% in the first second and third year of the pandemic whereas visits for children with known MI increased from 0.96% in the pre-pandemic year to 1.71% and 1.85% and 1.27 the first and second and third year of the pandemic. Overall, eating disorder presentations increased significantly through all three years of the pandemic compared to the pre pandemic year and admission rates were similar during the pandemic years.

Conclusion: The percentage of MI related visits to the paediatric ED increased significantly during the pandemic, for both new onset and known mental illnesses.

Keywords: Mental Illness; Mental Health; Children, Pandemic; Emergency Department; Covid 19

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic had a profound impact on the world and has resulted in widespread suffering and loss of life [1]. Of note, the paediatric population has been less severely affected by medical complications of COVID-19 compared to adults [2,3], and containment methods implemented to battle the covid pandemic have led to an overall decrease in emergency department (ED) visits during the initial stages of the pandemic [4-6]. Nonetheless, the pandemic has had deleterious effects on children’s mental health, with several studies showing an increase in anxiety, depression, and other mental illness (MI) related complaints [7,8]. While the absolute number of MI related ED visits was variable at the onset of the pandemic in 2020, with some reporting a decrease in MI related visits [9-11], almost all studies have shown an increase in the proportion of MI related ED presentations , especially in the second half of the 1st year of pandemic [5,6,12-17]. Although it seems that the pandemic has led to an increase in many MI related symptoms in the community, some have suggested that ED visits for MI related complaints are mainly reserved for the more severe cases of MI, such as those involving risk of self-harm [6,12,13], similar to presentations prior to onset of the pandemic [18]. In addition, literature shows that children with some MI seem to be more vulnerable to the effects of the pandemic [16].

The pandemic and measures employed to manage it have brought rapid changes to the lives of all, with loss of structure and daily routines, decreased opportunities of socialization and social isolation, loss of support mechanisms including those provided by schools [10,11]. These changes had a toll on everyone, and especially on adolescents and young children who usually lack the emotional and mental resilience to deal with emotional hardship compared to adults [8,9,19]. These effects are theorized to be even more pronounced in children already dealing with mental health disorders [10,11].

While several studies have focused on the effect of the pandemic on paediatric mental health, studies examining the differential effect it had on those previously dealing with mental health disorders have been scarce, with at least one showing an increase in MI visits by those with prior MI diagnosis [13]. Studies had contradicting findings regarding the admission rate of MI during the covid pandemic, from an increase [3, 13], to no change or a decrease in rate of admission [13,16]. This study aims to examine the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on ED visits for mental illness in the paediatric population, focusing specifically on the differential impact of the pandemic on children with new onset and known MI.

Objectives

The objective of this study was to identify changes in presentations of children with new onset mental illness and those with a pre-existing mental illness diagnosis during the Covid-19 pandemic in a paediatric emergency department.

Materials and Methods

A retrospective chart review of patients under 18 years of age who were treated for mental illness at the paediatric emergency department from March 1, 2019, to September 29, 2022, at a tertiary care children’s hospital in Canada was conducted after obtaining institutional ethics approval. The study collected data on patients’ demographic information, pre-existing conditions, presentation, and disposition information between those who sought treatment during the pre-pandemic year and those who presented during the first, second, and third years of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Additionally, the patients’ previous MI were classified into comparable groups, resulting in the identification of the following patient groups:

i. New onset MI visits.

ii. Those with a history of known mental illness presenting with.

a. Exacerbation of known MI.

b. New presentation leading to another MI diagnosis in those with known MI.

The patients’ ED visit discharge diagnoses were classified into several mental health diagnosis groups based on ICD 10 codes. Of note ICD 10 identifies suicides and intentional selfharm by poisoning or overdose of substances as a primary diagnostic category and they were grouped as such [20]. Data regarding previous mental health disorders, chronic conditions and previous diagnoses were extracted automatically from the electronic medical records (Epic) and 10% of them were manually checked for accuracy. The primary diagnosis of a prior visit was for mental illness in the institution only was used to identify prior mental illness. The institution is a tertiary care paediatric hospital with a psychiatry ward and provides psychiatry assessments both in the emergency department and outpatient urgent care clinics.

Although co-existence of more than one mental illness diagnosis is possible and different symptoms can present at different times we subdivided the children with known mental illness, if a mental illness diagnosis was made at the ED visit that was different from previously diagnosed mental illness or illnesses. In instances where the discharge diagnosis did not necessarily suggest a mental health condition (e.g., decreased intake, irritability, altered mental status), the nursing triage notes were reviewed to ensure that the discharge diagnosis was indeed secondary to a mental health-related condition. In cases where uncertainty arose, a full chart review was conducted. SPSS 16.0 statistical software was used for the analysis and chi-square tests, or Fischer exact tests were used to compare subgroups as appropriate.

Results

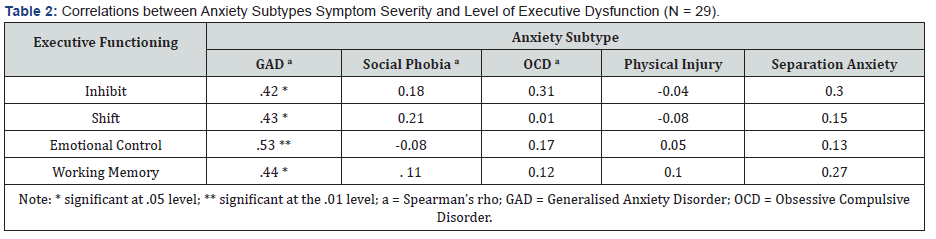

A total of 6431 ED visits related to mental health disorders were identified, which involved 5092 individuals. Most patients were biologic females (4084; 63.5%) with 97 (2.4%) identifying as non-binary or transgender. Among the 2347 (36.5%) children who were biologically males, 28 (1.2%) identified as non-binary or transgender. Mean age was 12.7 (SD ± 3.57) years. A total of 3173 (49.3%) had a known MI and 2333 (36.3%) were taking psychotropic medications. Compared to the pre pandemic year (2.04%), here was a significant increase in the proportion of MI related visits in the first (3.34%) second (3.5%) and third (2.92%) and third years of the pandemic (p < 0.001). Some of the common mental illness diagnosis in the pre-pandemic period and the first three years of the pandemic are listed in Table 1.

Period

New Onset MI

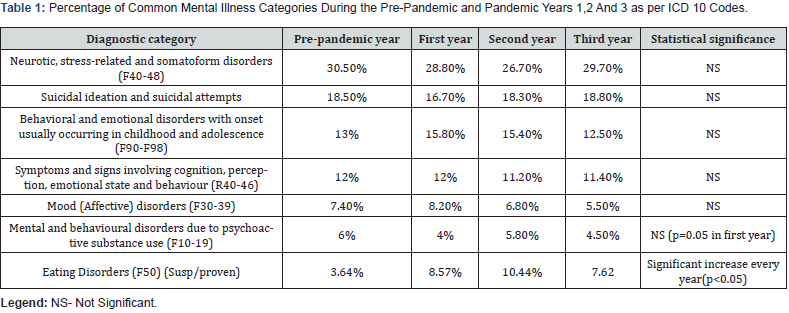

The proportion of new onset MI visits increased from 1.08% (852/78378) in the pre pandemic year to 1.63% (735/45158), 1.65 % (1054/63858) and 1.65% (617/37363) in the first second and third year of the pandemic respectively. Of all mental illness presenting to ED, new onset MI presentations were 53.3% in the pre pandemic year, which reduced to 49% and 47% in the two subsequent years of the pandemic and returned to 57% in the third year Table 2. New MI diagnosis increase was seen in the eating disorder category where it was 3.64% of all new MI diagnosis which went to 8.57%, 10.44%, 7.62% respectively in the first, second and third years of the pandemic (P< 0.001).

Patients With Known MI

The proportion of visits for known MI increased significantly from 0.96%(746/78378) in the pre-pandemic year to 1.71% (772/45158)and 1.85%(1180/63858) and 1.27%(475/37363) the first and second and third year of the pandemic. The percentage of patients with known MI presenting with exacerbations or new symptoms which was at 43.5% of all mental illness presentations increased significantly in the first (51.2%) and second (52.8%) years of the pandemic (p=0.01 and < o. ooo1 respectively). However, there was no statistically significant change compared to the pre-pandemic year in the third year of the pandemic (46.7%).

The common previous MI identified in children presenting with MI exacerbations and new symptoms were suicidal ideation and attempts (SI) (20.95%), neurotic, stress-related, and somatoform disorders (F40-48) (20.93%), mood disorders (F30-39) (13.28%) and eating disorders (F50) (11.48%). The percentage of patients with a history of SI/SA who presented with MI-related complaints significantly increased from 15.4% to 22.7% in the first year (p<0.0001,) and remained significantly increased at 23.4% in the second year (p<0.0001), and at 21.7% in the third (p<0.0001) of the pandemic. The percentage of patients with previously diagnosed history of mood disorders did not change significantly during the study period. The percentage of patients with neurotic, stress-related, and somatoform disorders (F40-48) also did not change significantly from pre-pandemic compared to the first 2 years of the pandemic. However, it was significantly reduced in the third year of pandemic from 21.2% to 16.7% (p=0.004)

The percentage of patients with a history of eating disorders significantly increased from 8.4% in the pre pandemic year to 15.9% in the first year of the pandemic (p<0.0001) and remained significantly increased at 11.9% in the second year (p=0.001). However, there was no significant change compared to prepandemic levels in the third year (9.1% vs 8.4%). There were no significant changes in other categories except for patients previously diagnosed with substance abuse where emergency visits significantly increased from 4.6% in the pre pandemic year to 7.1% in the first pandemic year (p=0.003) and remained significantly increased at 6.4% in the second year (p=0.013). In the third pandemic year, the difference was not statistically different (6.0% vs 4.6%; p=0.11).

Length of Stay (LOS) in the Emergency Department

Children with new onset mental illness had significant decrease in LOS (p<0.001) from pre-pandemic (292 ± 160) to first year (249 ± 149), followed by an increase in LOS in the next two years (326 ± 185) and (388 ± 187). A trend of decreased LOS in the first year of the pandemic, followed by an increase over the next two years, was observed in the patients with known mental illness but it was not statistically significant.

Hospital Admissions

Admission rates for all children with mental illness was at 21% in the pre pandemic year and increased significantly to 29% (p 0.001) in the first year and reduced to 25% and 22 % in the second and third years of the pandemic. In the pre pandemic year 30.6% of patients presenting with suicidal ideations or attempts were admitted which increased significantly to 41.3% in the first year(p=0.05) but was not statistically significant in the second (29.7%) and third years (32.3%) of the pandemic. Children with eating disorders had the highest admission rates in the pre pandemic year (63.6%) which was similar in the first (63.8%), second (57.8%) and third (62.2% years of the pandemic.

New MI presentations had no statistically significant change in admission rates compared to the pre pandemic rate of 2.1% during the first year (3.4%), but admission rates increased significantly to 5.5% in the second year (p<0.0001) and remained significantly increased at 5.2% in the third year of the pandemic (p=0.001). Patients diagnosed with MI presenting with exacerbation, had significant increase in the admission rate from the 49.3% in the pre pandemic year to 60.8% in the first year of the pandemic (p=0.0002). During the second and third pandemic year the rates were not significantly different from pre-pandemic year (50.7% and 54.1% respectively). For patients with MI presenting with new symptoms the pre pandemic admission rate of 30.41% did not change significantly in the three years of the pandemic (34.52%, 24.53% and 21.9% vs 30.41% respectively. Admission rates for patients with known MI on psychiatric medications were not statistically different from those who were not on psychiatric medications.

Discussion

Our findings support previous studies that have reported an increase in MI during the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as an increase in the proportion of MI-related visits to ED [6,7,13]. However, the distinction of new onset mental illness and exacerbation in children during pandemics has not been previously described well in the literature. Interestingly, during the first 2 years of the pandemic, a greater proportion of ED visits for MI were for exacerbation of symptoms rather than new onset mental illness compared to the pre-pandemic period. This suggests that the pandemic tends to exacerbate existing MI symptoms to a greater degree compared to causing new symptoms. However, this increase was not statistically significant in the third year of the pandemic, suggesting a shift back to the baseline of the prepandemic period.

It is worth noting that whilst some previous studies have also discussed the more severe effect of the pandemic on patients already suffering from MI disorders [10,11,13,20], others have indicated that children with high levels of mental health problems before and during the pandemic were less likely [20], or at least as likely [21] as their healthy peers to display an increase in mental health problems in response to the onset of the pandemic.

In our study we observed an increase in the proportion of patients presenting for MI complaints who had a history of suicidal ideations or attempts and those with eating disorders. This increase was more pronounced during the first two years of the pandemic, again suggesting a gradual return to baseline levels in the third year of pandemic. These findings are consistent with previous studies that have shown that individuals with these disorders are at higher risk of being affected by the COVID-19 pandemic [22].

Our study also found no significant increase in the proportion of patients presenting with mood disorders, which is consistent with previous reports suggesting that ED visits are increasingly reserved for more severe cases involving a risk of self-harm [7,16]. Therefore, the true rate of mood disorders in the community may not be accurately reflected by ED visits alone.

In our study, we observed that the highest admission rates were for those presenting with an exacerbation of a known MI. This finding was not surprising, as children who present to the ED with an already known condition may represent a situation where they have failed outpatient management or are unable to receive the help they need in the community setting, while those who present with new onset symptoms may simply require reassurance, education, and referral for appropriate services. While some previous studies have reported an increase in admission rates during the pandemic [6,12,13], not all studies have found this to be the case [16].

During the first year of the pandemic, the rate of admission increased in our institution and the reasons for this are challenging to discern. One possible explanation is that there were fewer community resources available, another explanation might be related to more severe presentations during the pandemic. The fact that children with a first-time presentation of MI symptoms were more likely to be admitted during the second and third years, but not during the first, is not well understood.

When children experience mental distress without access to evidenced-based interventions, their risk of relapse is seven times higher than those who receive treatment services [23], and as psychiatric hospitalization is a major contributor to high health care costs among children suffering from MI, providing a suitable work frame to address acute presentation of MI in a timely fashion and limiting hospitalization can help reduce costs [24].

Limitations

The study is a retrospective chart review in a single institution that relies heavily on the completeness of documentation in the charts and is limited by what is available on the charts. Data regarding previous mental health disorders, chronic medications, and previous diagnoses were extracted from the electronic medical records available at our site, and missing entries or visits to other hospitals may have affected our study results. However, we have no reason to suspect that the completeness of data has significantly changed between groups or over the study period. Therefore, we have assumed that any omission in the data entry would be random and equal over the various groups. As such, we do not anticipate any major errors in data collection.

Furthermore, our study is based on data from a single tertiary care paediatric hospital, and the findings may not be generalizable to other locations with different patient populations or healthcare systems. In addition, our study period was limited to the first three years of the pandemic, and future studies are needed to examine the long-term impact of COVID-19 on paediatric mental health. It should be noted that it was not possible to distinguish between the effects of the pandemic itself and the effects of the public health measures taken in response to the pandemic, such as school closures and social distancing. These measures may have had an impact on children’s mental health, but we were unable to quantify their effects.

Finally, our study was not designed to establish causal relationships between COVID-19 and mental health outcomes. While we observed associations between the pandemic and certain mental health conditions, further research is needed to determine the underlying mechanisms of these associations.

Conclusion

MI related visits to the Paediatric ED increased significantly during the pandemic, for both new onset MI presentations and exacerbation of previously diagnosed MI with increases being more pronounced in children presenting with exacerbations. The study results will hopefully aid in identifying populations that are at-risk for worsening MI and help us better target preventative strategies and guide resource utilization for the management and treatment of vulnerable individuals.

To Know more about Academic Journal of Pediatrics & Neonatology

To Know more about our Juniper Publishers