Gerontology & Geriatric Medicine - Juniper Publishers

Introduction

As clinicians it is not only important to know which clinical interventions work, but also why they work. When we understand the building blocks and processes underpinning an intervention, we can improve it based on the theory. This article examines the behaviors of people with dementia using Kahneman’s (2011) notion of ‘fast and slow’ thinking. Kahneman’s ideas help explain why people with dementia can continue to perform complex activities into late stage dementia (knitting, ironing, playing a musical instrument, riding a bike, driving a car). The ‘fast and slow’ model can guide us on how to support skilled activities and to interrupt processes that might lead to illbeing (e.g. repetitive questions or acts).

Understanding the processes underpinning a typical behavior in dementia

Maria, a woman with dementia, has the intention to go to the shops to buy a crusty loaf. She leaves her home with this firm intention, but an hour later we find her knocking at the door of a house where she had lived 10 years earlier. She is shouting and demanding to see her child. This type of memory failure is common in people with dementia. It is important to try to understand the mechanisms underlying memory failure because they provide information about how to deal with distress and maintain wellbeing in people with dementia.

If we had observed her during this trip, we would have noticed Maria making a number of choices as she went on her journey. Her first choice point came when she arrived at the junction of her street, she should have turned left to go to the shops but instead turned right. Having turned right, she eventually came to the entrance to the park. She opted to go into the park. After a short walk she exited the gates on the far side, and then she decided to take the no. 5 bus. This took her near her son’s ‘old’ school. She alighted from the bus but found the school closed and so progressed to the house where she had previously lived.

Ignoring the fact that Maria has dementia for a moment, her behavior reveals something important about the way humans process information. This is most eloquently described in the work of Kahneman [1] in his notion of ‘fast and slow’ processing. Kahneman suggests that slow thinking is conscious deliberate thought, whereas fast thinking is quick and often unconscious processing. The two features operate together whereby the slowed thinking creates the conscious goals, and ‘checks in’ every so often to ensure our plans are on track. In contrast, the fast-automatic processing enables us to carry out routine activities without using too much effort or thinking power. In other words, it allows us to ‘run in autopilot’ – see box 1.

Box 1

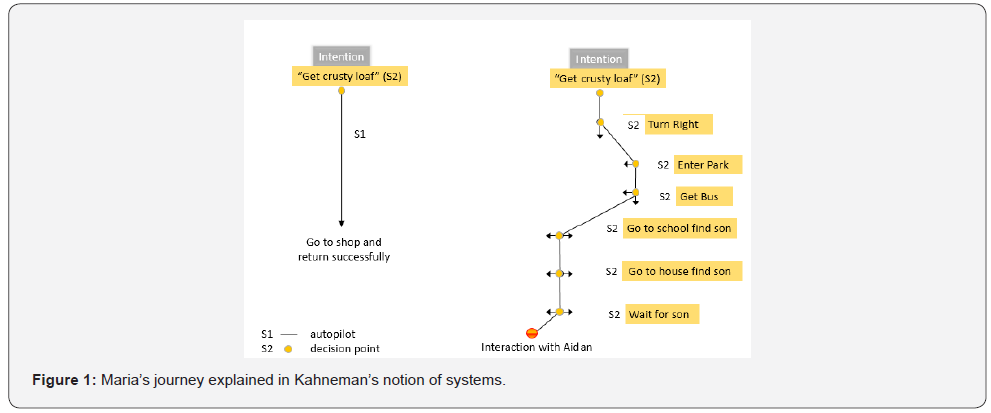

In terms of Maria, we see her engaging in fast and slow thinking, but her poor short-term memory means she has an inability to remember and focus on her original goal (getting the crusty loaf). Therefore, instead of basing her decisions on this goal, they are based on cues that she is encountering on her journey (e.g. the no.5 bus, school, vicinity of house). She is ‘running on auto-pilot’, relying on system 1 to do a lot of fast, automatic decision-making based on her environment. During this time, her slow system 2 keeps ‘checking-in’ to see if she is ‘on track’ but cannot remember what the goal is. She is moving around like a pin-ball in a pin-ball machine, making new goals and decisions based on whatever information is available to her. A representation of Maria’s information processing is shown in (Figure 1).

The final part of Maria’s journey is particularly important because here we see evidence of her remembering a goal over a sustained period of time (i.e. the desire to see her son). This goal was cued by passing his old school. In her time-shifted state, she thinks her son is a schoolboy and wants to collect him. However, because the building is closed, she panics and decides to go home (‘old’ home) to find him. This is relevant because she seems able to retain this goal for a longer period of time than she was able to remember that she wanted to get a crusty loaf. This is almost certainly because of the high level of emotion attached to seeing her son, as emotional memories are retained more easily for people with dementia.

Clinical Relevance

The above scenario, and its theoretical underpinnings, are relevant to clinical practice. Indeed, in addition to having explanatory power in relation to Maria’s journey, it offers guidance in two other important areas (i) the de-escalation of challenging behaviors (CB), and (ii) the selection of treatments in dementia.

(i) De-escalation of CBs – In a typical de-escalation situation people with dementia have got a particular goal and their attempt to fulfil this may put themselves, or someone else, at risk. However, the caregiver’s attempt to intervene may be perceived by someone with dementia as interfering or over-controlling which can further inflame the situation and lead to aggression.

Such a situation is about to happen in Maria’s scenario because she is now trying to find her son, and bangs on a stranger’s door; the goal and drive to see her son is strong. The poor unsuspecting occupant of the house, Aidan, is about to encounter a difficult situation. If he responds to Maria in a way that further upsets her, the situation could become problematic and he may get assaulted. Fortunately, however, Aidan works at the local care home and is skilled in dealing with such situations. He recognizes Maria has a dementia and guesses correctly that she is time-shifted. Hence, he knows that a direct confrontation of her current view would be unhelpful. He is aware that he needs to ‘go along’ with her current view of reality for a while and look for an opportunity to grab her attention with a powerful topic of distraction. By doing this he knows that he will have a chance to re-orientate her to the present and the current reality.

Aidan invites Maria into the house and says she can wait to see if her son comes home. Despite being agitated she sits and accepts a cup of tea. Aidan’s friendly chat calms her and reduces her ‘emotional thinking and her drive’ somewhat. He notices that she is taking a lot of interest in his Labrador and asks does she like dogs. Maria is a big dog lover and she is soon talking enthusiastically about the many dogs she’s owned. Aidan is hugely attentive, asking lots of questions about her dogs. Five minutes later Maria has been distracted from her son. Aiden doesn’t want Maria to be reminded of her son again, so he asks his own children to stay out of the room until her taxi arrives.

Aidan did something really simple here, something that many caregivers do without recognizing the processes underpinning it. Aidan’s choice of topic, and the enthusiastic manner he used to engage Maria, resulted in a shift from ‘children’ to ‘dogs’. We can see how fast and slow thinking underpins this interaction because we can understand how the CB stems from cues in the environment altering her goals (slow thinking) and short-term decisions (fast thinking). In this situation, Aiden is able to use this to his advantage by encouraging Maria to focus on different, more helpful cues like his dogs. This redirected her slow thinking to forget about the goal of seeing her son so that her fast processes were anchored in the current situation rather than focused on this outdated goal. He also removed cues which could retrigger her distressing thoughts of her son.

In clinical practice we can use this idea to:

a) Identify what elements of the environment are triggering the goals and thoughts behind CBs

b) Remove these cues to prevent CBs.

c) Introduce topics and cues that can redirect attention to more situation-appropriate thoughts and goals which are anchored in the present (or away from the distressing thoughts).

(ii) Selection of treatments in dementia – The term treatment can be confusing because it could refer to interventions to either reduce the rate of the dementing process or to tackle agitation or aggression. However, in the current discussion the interventions are designed to maintain wellbeing.

Unfortunately, the evidence base for effective wellbeing treatments is rather inconsistent, except in case of Cognitive Stimulation Therapy (CST) and some person-centered programs [2]. In part, this is due to the fact that dementia includes a wide range of diseases which may be at many different stages, and also that the experience of dementia is different for every person. This means that studies which might show positive effects of interventions in some cases are watered down by the fact they may not be appropriate for every individual at every stage.

To deal with such variability, occupational therapist (OTs) have produced a number of programs that attempt to match interventions to the stage of the condition [3]. We suggest that the effectiveness of the OT frameworks can be further enhanced by factoring-in Kahneman’s notion of ‘fast and slow’ processing. Let’s look at the implication of Kahneman’s ideas with respect to people with moderate to advanced dementia.

a) People with dementia have difficulties sustaining activities that require the retention of long-term goals or strategies (slow thinking). Therefore, the use of prompts at key points would be helpful.

b) Activities that include overlearned activities (procedural memories and fast thinking) can be exploited and are able to provide a sense of accomplishment. However, to maintain the person’s active participation he/she may require assistance at transition points between actions which require slow thinking (e.g. when baking a cake the person may struggle with regulating the oven; selection of ingredients; timings).

c) If the tasks fulfil some basic emotional needs (fun, touch, being active, sense of belonging, feeling safe) they are more likely to be engaged initially and their interest and understanding of the activity is more likely to be sustained [4].

Kahneman’s ideas lead us to promote activities that provide positive experiences ‘in the moment’ that do not require goals or strategies (e.g. listening to music, speaking with an attentive listener, looking at photographs, engaging with table-top interactive touch games). It is also helpful to choose actions that provide immediate feedback because this facilitates the use of ‘autopilot’ activities. It is worth noting that the above recommendations are not new and many of them are being done intuitively by experienced cares. However, what is different is that the theory informs us why the approaches are effective. Further, if we start to understand the building blocks of such interventions, we can produce more effective treatments. Therefore, what we are offering here is the theory underpinning the choice of intervention.

An example of this idea can be seen in a study we undertook in 2014 in which we spoke to Christian clerics about their experiences of providing religious services to people with dementia [5]. The most exciting part of this project was to see people with advanced dementia, who appeared to struggle to speak in a residential setting, suddenly become engaged and lively during the religious service. One person attending a Catholic mass fully participated in the prayers, hymns and symbolic aspects of the service. She smiled throughout, seeming to have a sense of belonging in a community from which she had previously appeared detached. Such projects need to be replicated across other religious groups and across other such communal topics. However, the key point being made is that the woman attending the service was able to participate in the service through a mixture of fast and slow processes. She knew the prayers and hymns once they had begun (fast thinking) and was being guided through the transitions by both the structural elements provided by the mass and the behaviors of the other members of the congregation so she was not reliant on slow thinking and retaining information about the service.

‘It is’ and ‘it isn’t’ child’s play – activity in the moment

Before concluding the article, it is worth reflecting on the skills required to devise activities for people with dementia. A good activity for someone with an advanced dementia is something that does not require a goal or strategy – this is where dominoes is better than draughts, which is superior to chess. Further, the actions associated with the task need to be basic and intuitive, another reason dominoes is good (involving a simple matching task), and why the card game ‘snap’ would be more appropriate than either ‘whist’ or ‘poker’.

Also, it is better to use activities that can be undertaken and enjoyed ‘in the moment’, and ones that rely on reflexes: playing simple instruments, ‘copy-cat’ yoga, simple ball games, etc. It is worth noting that games that are traditionally used with small children contain features that make them ideal in late stage dementia. Childhood brain development and brain deterioration have overlapping phases and therefore the types of activities that are suitable for children may be relevant for people with dementia.

It is important to remember however, that unlike children, people with dementia have an array of skills that have been developed in the past that can be utilized if the correct cues are employed. This is well illustrated in the church service example. In this case, a vast range of skills were unlocked once we had provided the person with an environment that supported and triggered the expression of their skills.

To Know more about Gerontology & Geriatric Medicine

Click here: https://juniperpublishers.com/oajggm/index.php

No comments:

Post a Comment