Diabetes & Obesity - Juniper Publishers

Abstract

Background: Compounded errors during insulin

administration may impact the efficacy of diabetes control. Our major

objective was to quantify the various errors committed by patients

during insulin therapy.

Methods:This was a multicentric,

observational study in which participants were asked to respond to a

specific questionnaire under the supervision of a trained nurse,

addressing problems and risks of insulin self-administration. The study

included 140 individuals aged 6-75 years, with type 1 or type 2 diabetes

on insulin for more than 6 months, allocated to adults or youth groups.

Results:Comparing performance of adults vs

youth groups for withdrawal of 7 IU the rates of correct doses were

66.7%vs100% with 30U syringes (p=0.002); 70.8%vs95.0% with 50U syringes

(p=0.022); and 50.8%vs40.0% with 100U syringes (p=0.370), reflecting

poor performance in both groups. With the target dose of 22U, the rates

of correct doses were 67.5%vs100% with 30U syringes (p=0.003);

66.7%vs95.0% with 50U syringes (p=0.010); and 52.5%vs50.0% with 100U

syringes (p=0.836), again reflecting poor performance in both groups

with a higher dose. Other major errors included: improper rotation

technique in 62.5% of patients; failure to lift a skinfold in 29.2%;

premature withdrawal of the needle from injection sites in 45.8%;

totally correct injection technique was documented in 10%.

Conclusion:The results of the study point to

the urgent need for implementation of effective educational strategies

to provide patients with basic knowledge needed to minimize the

potential risks of insulin self-administration, including use of

appropriate insulin syringes according to size of injection dosage.

Keywords: Insulin therapy; insulin injection errors; insulin administration safety; diabetes treatment

Introduction

An overall assessment of glycemic control around the

world shows that only a small fraction of patients with type 2 diabetes

(DM2) achieve adequate glycemic control even after several years of

treatment [1-4]. In Brazil, 73% of patients with DM2 and no less than

90% of patients with type 1 diabetes (DM1) have poor glycemic control

(A1C > 7%), as shown by a recent Brazilian multicenter study in 6,671

patients across several diabetes care centers throughout the country

[1]. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the

percentage of adults with diabetes in the United States with A1C>7%

reached 43% during the period of 2003-2006 [5].

The growing population of people with diabetes has

assumed epidemic proportions worldwide, with a consequent significant

increase in the number of insulin users. At the same time, wrong

information about correct techniques of insulin self-administration is

widespread and the consequences are highly worrying, since

incorrect delivery results in substantial modification of the

pharmacological action of insulin. This problem motivated a group of

leading medical experts and diabetes educators to develop New Injection

Recommendations for Patients with Diabetes, published in 2010 [6].

In patients with DM1 insulin therapy is an absolutely

requirement. On the other hand, increasing number of patients with DM2

need insulin treatment when oral therapeutic options do not lead to

desired glycemic control. However, resistance to initiating insulin

treatment is frequent among physicians and patients with DM2, which

slows or prevents the implementation of more intensive treatment

regimens, with obvious negative consequences in terms of chronic

complications of the disease. This refusal is mainly due to misbeliefs

on the part of patients, which includes fear of insulin injections. When

insulin is begun, this rejection is compounded by poor insulin

administration techniques that need to be urgently addressed and

overcome [7]. The condition known as “clinical inertia” applies when the

patient’s clinical conditions clearly indicate the need for

intensification or adjustment of the therapeutic approach, but

it is delayed-often for years in the case of insulin for DM2 [8]. A

publication by the American Diabetes Association lists the most

important myths and facts related to insulin administration [9].

The proper appreciation of the concept of “compounded

error” is essential to understanding the increased risk represented

by the combination of individual errors during insulin selfadministration.

According to the Merriam-Webster dictionary the

term “compound” refers to an error, condition or problem that

makes any outcome even worse [10]. Inadequate guidance and

patient compliance in relation to insulin self-administration are

two of the major problem areas among the education initiatives in

diabetes. In general, patients frequently receive a prescription for

insulin with little, if any basic orientation on the correct techniques

that will lead to successful treatment. The various technical errors

committed by patients in insulin self-administration are already

well-known to health care professionals but, to our knowledge,

have never been properly quantified. The Diabetes Education and

Control Group of the Kidney Hospital, Federal University of Sao

Paulo-UNIFESP promoted and coordinated a multi-center study in

order to identify and quantify the occurrence of technique errors

during insulin self-administration [11].

Material and Methods

This was an observational, non-interventional study in which

participants were asked to respond to a specific questionnaire

addressing the main problems and potential risk factors related

to insulin self-administration. In addition they were asked to

perform a practical demonstration of how they withdraw various

insulin doses from the vial into different syringes. The patients did

not have to inject the selected insulin dose.

Patients of both sexes, on insulin for more than six months,

aged 6-75 years receiving care at the Unified Health System

(SUS) in the six participating centers were chosen at random. The

study enrolled 140 individuals with type 1 or type 2 diabetes:

the coordinating center included 40 individuals and each of the

other five participating centers included 20 individuals. Patients

were allocated to two groups: adults (120 individuals) and youth

(20 children, adolescents and young adults with DM1). Nurses

responsible for implementing the study questionnaire in the

various centers received special training and were supervised

by a medical professional in each participating center. The

questionnaire contained 23 questions and practical observations

on insulin injection technique outlining errors commonly made

by patients (available at the appendix). The Study Protocol was

approved by the Research Ethics Committees (ECs) of each

participating center. The individuals included in the study or

parents or legal guardians signed consent forms in the case of

children and minors signed an informed consent to participate

in the study, which was conducted consistent with Good Clinical

Practice guidelines and the Declaration of Helsinki.

Primary objectives of the study included: to obtain information

enabling a proper mapping of insulin self-administration

practices in the public health service; to evaluate the adequacy

of self-administration techniques used by patients; to evaluate

the main problems and potential risk factors involved in insulin

self-administration which may influence clinical outcomes and

the safety of insulin treatment. Secondary objectives of the study

included: to evaluate the demographics of a sample of 140 patients

under insulin treatment; to obtain information on prescribed

doses of intermediate, long- and short-acting insulins used by

these patients.

The following parameters were evaluated by the

attending

nurse after patients’ demonstration: rotation technique was

assessed as correct or not; presence or absence of lipohypertrophy

was evaluated by clinical examination; and grading of injection

technique as correct, partially correct, or incorrect. Dose accuracy

testing (acceptable variation = prescribed insulin dose ± 1 IU) was

conducted by assessing the patient›s ability to draw the correct

doses of the prescribed insulin as directly observed by the nurse in

charge. Initially, the patient was asked to draw up a dose of 7

IU of insulin, using 30 IU (1-unit scale markings), 50 IU (1-unit

scale markings), and 100 IU syringes (2-units scale markings),

manufactured by BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA. Then, the same

procedure was performed by the patient with a dose of 22 IU,

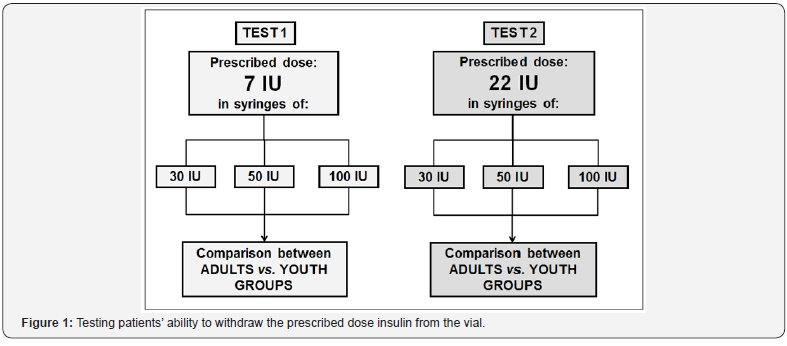

using the same syringes, as shown in (Figure 1). The 7 IU testing

dose was chosen for being a low and odd number and the 22 IU

testing dose was chosen for being a higher, even dose so that

accuracy was tested in two different situations.

Statistical Analyses

Categorical data were summarized by absolute and relative frequency of cases in relation to the total number of patients from

the adults and youth groups. Data with a normal distribution of

numeric and continuous parameters (e.g. ages) were summarized

as mean and standard deviation in each group together with

minimum, median and maximum values. Other parameters were

evaluated by median and quartile values. Adults and youth groups

were compared with respect to the percentage of patients who

had correctly withdrawn the requested insulin doses from the vial,

via the chi-square test. The statistical comparison of the number

of patients who made mistakes in the withdrawn dose with 100 IU

syringes compared to the 30 IU and 50 IU syringes was performed

using the McNemar test.

To check the characteristics of patients related to correct

and incorrect doses, the chi-square test was used on categorical

variables, and the Student’s t test in the variables with numerical

and continuous distribution. Statistical significance thresholds

were set at p <0.05. The data were obtained using the Minitab

statistical software, version 16.1.

Study Results

Patient Characteristics

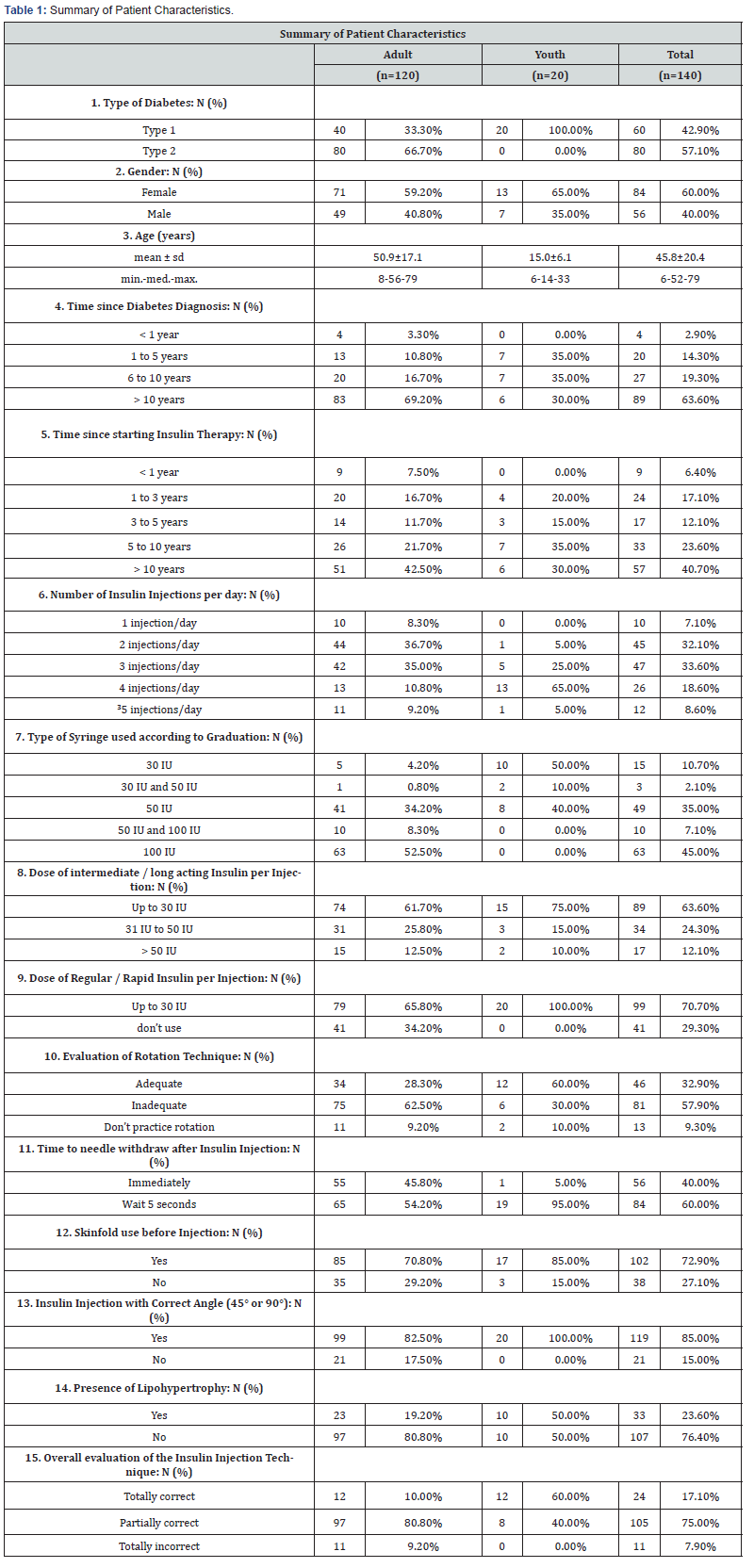

(Table 1) shows the characteristics of patients with respect

to demographics, diabetes-related data and insulin delivery

practices in adults, youths, and in total group. An overview of the

study population showed that two-thirds of the adults were DM2,

with a slight preponderance of females. Adults were nearly 51

years of age on average, and youths, 15 years. Mean years since

diagnosis for more than 10 years were 2.3 times more frequent

in adults compared to youth. Considering the period of time

of >10 years adults were 1.4 times more experienced with insulin

therapy than the youth. Frequency of daily injections was higher

in youth compared to adults.

In the total group of our study population, the 100 IU syringes

were being used by 45.0% of patients, the 50 IU syringes by 35.0%

and the 30 IU by just 10.7% of patients, respectively. Either 30 IU

or 50 IU were used by 2.1% and either 50 IU or 100 IU were used

by 7.1%. Average doses up to 30 IU of intermediate/long acting

insulin and regular/rapid insulin were more frequent in both

adults and youth. Inadequate rotation technique was twice more

frequent in adults. Only 1/10 of adults and 1/10 of youth did not

practice rotation. A high percentage of adults and youth performed

skinfold before injections. Insulin injection with correct angle

(45º or 90º) was a frequent practice both by adults and youth.

Lipodystrophy was 2.6 times more frequent in youth, compared

to adults. In the overall evaluation of insulin injection technique

by the supervising nurse the percentage of youth practicing the

correct technique was 6 times higher in youth than in adults.

Correct and incorrect Insulin Doses withdrawn from the Vial

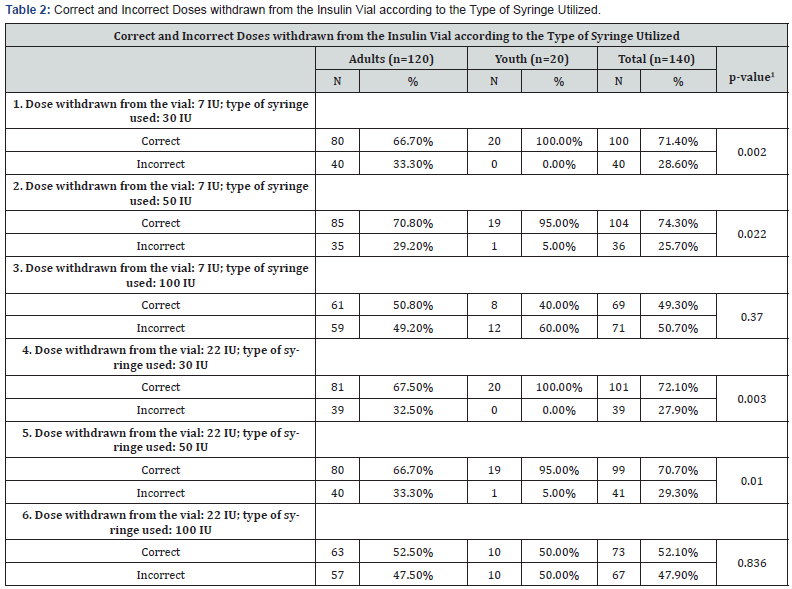

In relation to the precision in withdrawing the correct dose

from the vial, the statistical comparison between adult and youth

groups showed that young patients make less errors than adults

when using 30 IU or 50 IU syringes, whether in drawing 7 IU dose

(p = 0.002 for 30 IU syringe; p = 0.022 for 50 syringe IU) or in

drawing 22 IU dose (p = 0.003 and p = 0.010 for 30 IU syringe and

50 IU syringe), but there is no significant difference when used

syringes of 100 IU (p=0.370 for the 7 IU dose and p=0.836 for the

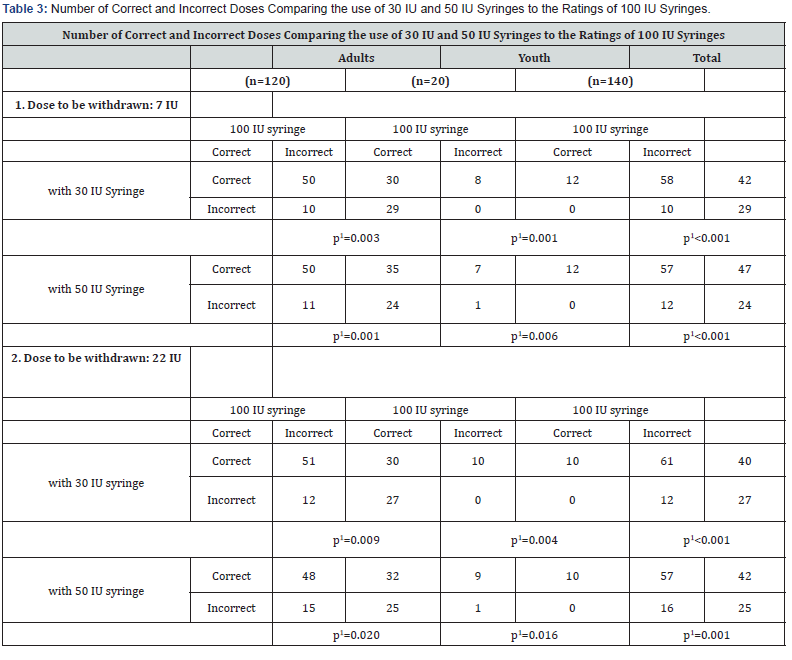

22 IU dose) (Table 2). The superiority of 30 IU and 50 IU syringe in

comparison to 100 IU syringe in terms of accuracy in withdrawing

the correct insulin dose is well stablished as seen in (Table 3).

In relation to the precision in withdrawing the correct dose

from the vial, the statistical comparison between adult and youth

groups showed that young patients make less errors than adults

when using 30 IU or 50 IU syringes, whether in drawing 7 IU dose

(p = 0.002 for 30 IU syringe; p = 0.022 for 50 syringe IU) or in

drawing 22 IU dose (p = 0.003 and p = 0.010 for 30 IU syringe and

50 IU syringe), but there is no significant difference when used

syringes of 100 IU (p=0.370 for the 7 IU dose and p=0.836 for the

22 IU dose) (Table 2). The superiority of 30 IU and 50 IU syringe in

comparison to 100 IU syringe in terms of accuracy in withdrawing

the correct insulin dose is well stablished as seen in (Table 3).

It is also observed that for the 7 IU dose the number of wrong

doses increases significantly when using 100 IU syringes both

among adults (p = 0.003 and p = 0.001, using the 30 IU and 50 IU

syringe, respectively) and among youth (p = 0.001 and p = 0.006

using 30 IU and 50 IU syringes, respectively). Similar results were

observed when the test dose of 22 IU was used (Table 3).

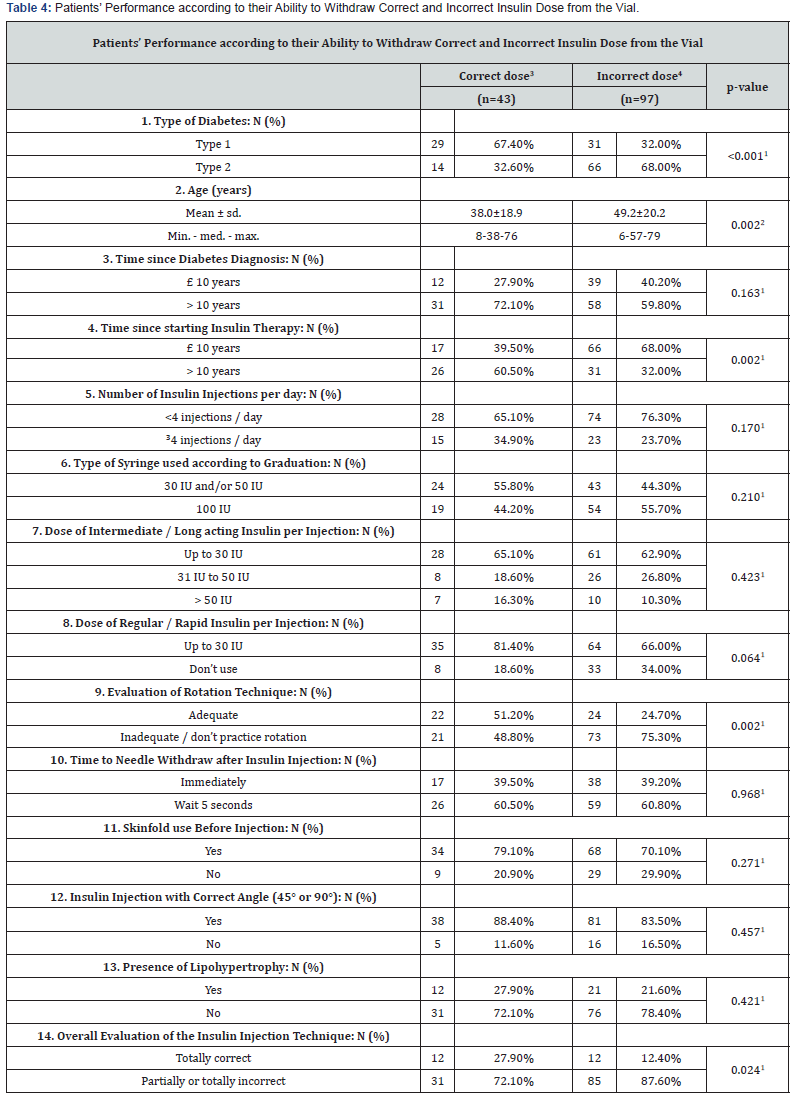

Characteristics of patients who scored or missed the dose to be withdrawn

Patients were classified according to their accuracy in

drawing up the correct or incorrect insulin dose from the

vial. A correct dose was defined as drawing up 7 IU ± 1 IU and

22 IU ± 1 IU, regardless of the type of syringe used (30 IU, 50 IU

and 100 IU). If any dose was drawn incorrectly, it was considered

«error» (Table 4).

1Chi-square test ; 2Student’s t test;

3Correct dose in drawing the insulin dose from the vial (7 IU and 22

IU), with any of the syringes utilized (30 IU,

50 IU, 100 IU); 4any error in terms of dose withdrawn from the vial (7

IU and/or 22 IU), with one or more syringes (30 IU, 50 IU, 100 IU).

Discussion

Insulin self-administration is often done incorrectly, and

this can lead to risks, especially when different types of errors

occur simultaneously (compounded errors) [12,13]. These

issues, summarized in (Table 1), can substantially modify the

pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of injected insulin,

greatly increasing the risk of hypo-or hyperglycemia. Among the

many errors occurring during self-administration of insulin, the

most serious and unforeseen is the incorrect drawing up of doses

from vials.

Despite rapid technological advances in insulin formulations

over recent years, injection technique has not been given much

attention in the management of injectable therapies [14]. Our

study reveals a number of critical problems related to basics of

insulin injection technique that may interfere with its expected

pharmacological profile. Many problems can be avoided by

adopting proper technique [6]. Theoretically, it should be expected

that errors in insulin administration could be more frequent in

patients who are less experienced with the disease and, more

specifically, with the practice of insulin therapy.

(Table 4) shows the characteristics of patients according to

correct or incorrect withdrawn dose. It can be observed that the

type of diabetes (DM1 or DM2), age, time since start of therapy

with insulin, the insulin administration rotation technique (proper / improper) are factors that correlate to correct or

incorrect doses in withdrawing insulin dose. Patients who

make more mistakes in withdrawing the insulin dose are older

(p = 0.002), with DM2 (p <0.001), who started insulin therapy

less than 10 years ago (p = 0.002), and that do not use proper

rotation technique or that do not rotate the insulin injection at

all (p = 0.002). Patients that were considered by the supervising

nurse as having poor insulin administration technique also made

more errors than those with a totally correct approach to insulin

injections (p = 0.024) (Table 4).

The results of the study also showed the higher performance?

of 30 IU and 50 IU syringes for the prevention of a major problem

in insulin self-administration. There is a substantial risk of

withdrawing incorrect doses when using 100 IU syringes, which

are graded by 2 IU, making it difficult the reading of syringe scale.

The replacement of the 100 IU by 30 IU or 50 IU syringes, according

to the needs of each patient, is an important preventive strategy to

avoid technical errors in insulin self-administration, particularly

for patients in the public health service who generally do not have

access to educational programs which provide adequate guidance

on the correct techniques for this procedure. To our knowledge,

no other study approached this problem with the 100 IU syringes

as a serious risk factor for in proper selection of insulin dose.

In the total group of our study population, the use of 100 IU

syringes was far more frequent than 50 IU syringes and 30 IU. If

the 100 IU syringes are the least safe option for insulin injections,

why not give preference to 30 IU or 50 IU syringes? The basic

question is the average insulin injection individual doses to make

sure that the volume of insulin utilized with the 100 IU syringes

would fit the available volumes of 30 IU or 50 IU syringes. Our

data show that a minority of our patients was using individual

doses greater than 50 IU of NPH or long acting analogs and all

of them were injecting less than 30 IU of regular or short acting

analogs or were not using short acting analogs at all. These data

indicate that the vast majority of patients could be using 30 IU or

50 IU syringes instead of 100 IU syringes. It should be noted that

patients who take both NPH and regular insulins in our service do

so with two separated injections instead of mixing in one single

injection.

The other critical finding of the study was that 67.2% of

patients utilized improper rotation technique or did not rotate

at all. The consequence of improper site rotation technique is

the increased risk of lipohypertrophy, which is also related to

increased frequency of reuse of insulin needles [15]. In our study,

lipohypertrophy affected 23.6% of the study participants, but

this may be an underestimation due to diagnostic difficulty in

identifying small lipohypertrophy nodes (Table 1). Another recent

study on the prevalence of lipohypertrophy showed that 64.4% of

patient had this complication [16].

Another potentially problematic issue was the finding that a

fair proportion of patients removed the needle immediately after

the injection, without waiting the recommended 5-10 seconds.

The purpose of this dwell-time is to avoid reflux of insulin from

the injection site. Use of skinfold and injection with a correct

angle of 45º or 90º (according the clinical situation) for insulin

administration was reported by the majority of patients.

Study Limitations

This study addressed several aspects relevant to the good

practice of insulin self-administration. However, other key issues

have not been properly surveyed, including the following:

1. The unequal distribution of participants between the

adult group (n = 120) and the youth group (n = 20) may have

an impact on the interpretation of statistical significance of

differences found between the two groups. As shown in (Table 2)

2. Frequency and clinical impact of inadequate mixing of

NPH insulin for complete resuspension. In a study of 109 patients

using NPH insulin it was recommended that they should roll and

tip the pen cartridge at least 20 times in order to get adequate

insulin resuspension but, in fact, only 9% of these patients

actually tipped and rolled the cartridges more than 10 times. As

a consequence, NPH insulin concentration ranged from 5% to

214% and varied by more than 20% in 65% of the 109 patients

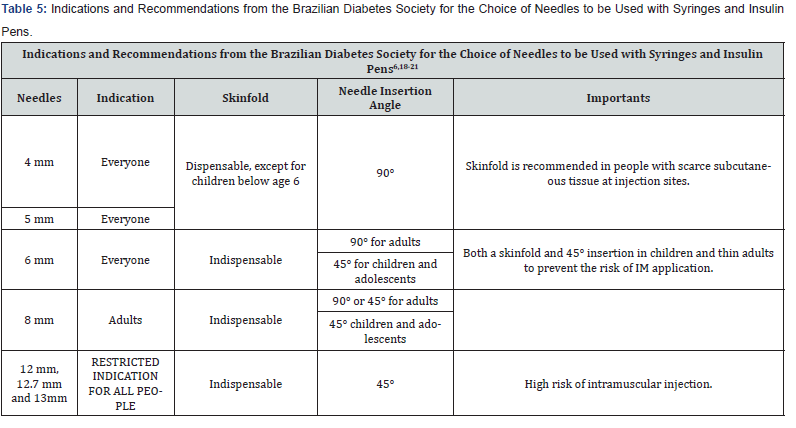

[17]. Directions and recommendations for the use of needles for

insulin syringes or pens are summarized in (Table 5), adapted

from the Brazilian Diabetes Society - 2014-2015 guidelines [18]

and other related papers [6,19-21].

Summary and Conclusion

There are several obstacles and technical errors commonly

observed in patients who practice self-administration of insulin,

significantly increasing the likelihood of unsuccessful treatments

[22-27]. The main topics that deserve full attention of the health

team responsible for guiding the diabetic patient are summarized

below:

1. Errors in insulin administration occur in clusters and in

line with the concept of “compounded errors”. Consequently,

the final negative impact is greater than the sum of

consequences of individual errors.

2. The myths that impair or impede the acceptance of

insulin by diabetic patient should receive proper attention

from health care team [28-30]. If this problem is not overcome,

it will be almost impossible to implement safe and effective

insulin therapy.

3. Although most of the study population already had

experience with diabetes and insulin therapy for more than

10 years, the frequency of important technique errors during

the study was a matter of deep concern.

4. Among all the observed problems, errors in the

withdrawing of the prescribed dose from the insulin vial

reached highly alarming proportions, since 50% of adults and

60% of younger patients drew up incorrect doses of insulin

when using a 100 IU syringes [31-33].

5. Although not included in the study objectives, it is

important to note that the 12.7 mm long needles represent

a high risk of intramuscular insulin injection and therefore

should be quickly replaced by 8 mm needles (or preferably,

6 mm) for syringe users and 4 mm or 5 mm for pen users [21].

6. Final message: the implementation of interdisciplinary

groups of diabetes education is a key strategy to overcome the

misinformation that is the biggest problem responsible for

the high rate of uncontrolled diabetes [34,35].

No comments:

Post a Comment