Juniper Online Journal of Case Studies - Juniper Publishers

Abstract

We describe the case of a previously healthy Norwegian 3-year-old girl who presented with recurrent episodes of high fever, poor appetite, vomiting and weight loss. For two months she had experienced episodes of high fever of unknown cause, especially at night. At admission the girl was pale with reduced general condition, and the liver was enlarged as well as the spleen. She complained of abdominal pain and was tender on palpation. Prior to her admission the family doctor had started oral antibiotics on suspicion of bacterial pharyngitis, but the symptoms and fever persisted. The girl had only been abroad once, last summer in the Mediterranean, two months prior to appearance of her symptoms. Fever in children can have many causes and this case highlights the diagnostic challenge of fever with unknown cause. The sum of thorough anamnesis, clinical suspicion, systematic and broad approach and specific examinations was decisive. PCR analysis of her bone marrow was positive for the parasite Leishmania, as well as findings of single-cell parasites by microscopy of blood and bone marrow aspirate. She was immediately provided liposomal Amphotericin B and recovered quickly. At 2 months follow-up she was well-functioning and healthy without fever episodes, organomegaly or anemia.

Keywords: Children; Leishmaniasis; Anemia; Hepatosplenomegaly; Fever

Abbreviations: AST: Anti Streptolysin Test; CRP: C Reactive Protein; IGRA: Interferon-Gamma Release Assay; HLH: Haemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis; NTD: Neglected Tropical Disease; VL: Visceral Leishmaniasis

Introduction

Fever and abdominal pain are common symptoms in children, even high fever with completely harmless viral infections. In general, the condition of the child is a more important indicator of how ill the child is than the temperature itself, but prolonged and recurrent fever, and lethargy, indicate underlying disease, especially if there is concomitant anemia and hepatosplenomegaly. Thorough medical records, systemic thinking and clinical examination are essential, and led to suspicion and specific investigation that revealed infection with the Leishmania parasite which has not previously been described in children in Norway. Immediate treatment probably saved her life.

Visceral leishmaniasis (VL) is a condition that can appear as a difficult differential diagnosis and a triggering cause of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) [1], which presents with fever, pancytopenia and organomegaly in endemic areas. The diagnosis of visceral leishmaniasis requires detection of the leishmania parasite in bone marrow or spleen aspirate, and possibly antibody detection.

VL is not endemic in Norway. The parasite is widespread in the southern Europe (4) including popular tourist destinations such as the Mediterranean basin [2,3]. Visceral leishmaniasis is a life-threatening infection with the protozoan Leishmania, transmitted by the bite of infected sandfly Phlebotomus argentipes [4]. The parasite affects internal organs such as lymph nodes, bone marrow, spleen, liver and the nervous system. Visceral leishmaniasis is classified as a neglected tropical disease (NTD) and 90% of the annual 1 million cases of the disease in the world occur in poor countries [3,5-7]. Only a small proportion of those infected develop VL and one may be infected without symptoms or signs of infection. VL is almost 100% fatal without treatment [3,7], and is considered the most serious of the so-called neglected diseases. Visceral leishmaniasis is relatively unknown to most medical practitioners in non-endemic areas such northern Europe and clinical vigilance is required to identify those who are infected. This aim of this case report is to highlight the importance of a detailed anamnesis, including travelling to endemic areas and popular tourist destinations as well as systematic thinking and follow-up.

Case Presentation

A 3-year-old girl, previously healthy, was referred to our hospital´s pediatric ward due to poor appetite, weight loss (from 12.4kg to 11.7kg) and vomiting over several days. Her anamnesis revealed recurrent episodes of high fever with temperatures above 40oC, especially at night.

Antibiotic treatment with penicillin provided by the family doctor who suspected airways infection, was discontinued at admission as bacterial infection was not suspected based on negative clinical effect and test results. At admission she was afebrile, pale and in poor condition. Physical examination revealed an enlarged spleen and liver, 3cm below the costal arch. C-reactive protein (CRP) was elevated (52 mg/L) with neutropenia (1.1 109/L) and borderline low platelet counts (158 109/L). She was respiratory and hemodynamically stable, and chest X ray was negative. The hemoglobin (Hb) concentration was 8.5 g/100ml (reference for age 11-13).

A week after admission her Hb had dropped to 7.7. Further investigations revealed elevated levels of ferritin (684mg/L (10-140)), transferrin receptor (13.1mg/L (1.5-3.3)), and haptoglobin MCV (70fL (75-87)), and microcytic anemia (MCH 20pg (22-30), MCHC 28g/dl (32-37), reticulocytes 206g/dL (20-95), immature reticulocytes of 0.30% (0.02-0.18)) and reticuloculocyte-Hb equivalent values 23pg (28-36), erythrocytes 3.9 1012/L (4.1-5.3).

Examination with blood smears and differential count performed 4 days after admission, showed no signs of malignancy.

She was discharged home after 12 days, when she had recovered well and been afebrile over the last 3 days. At discharge she agreed to take extra supplements of iron and come for an early outpatient check-up.

The girl was readmitted 4 weeks after discharge, due to febrile seizures. She was again strikingly pale and her Hb had dropped to 7.0g/dL, CRP was persistently elevated (58) and her pancytopenia had worsened; (leukocytes 1.0 109/L (4.4-12.5), neutrophils 0.2 109/L (1.0-8.5), lymphocytes 0.7 109/L (1.0-4.6), monocytes 0.1 109 / L (0.9-1.8) and platelets 62 109/L (145-390), all reference values per age). This was compatible with respiratory infection believed to be the cause of febrile seizures. She was in relatively good general condition and afebrile during the rest of her 2 days hospital stay, asked to recontact immediately if her condition worsened.

After another month the girl was readmitted. All family members were healthy except for the girl. Her mother was originally from Africa and pregnant in the last trimester when she came to Norway when she was tested negative for multi-resistant staphylococci (MRSA), HIV, toxoplasma and Triponema pallidum, and she was Rubella IgG positive. The girl was born in Norway. A delayed update of her anamnesis at this third admission revealed that she had been abroad once which was last summer in a country house up in the Spanish mountains.

At this last admission she had high fever with constant temperature of 40oC. She denied eating, was confused, exhausted and circulatory affected with tachycardia (160 beats /min). Liver and spleen were further enlarged by palpation, 6 and 9 cm below the costal arch, respectively. Organomegaly was also confirmed by ultrasound, which showed no other pathological findings. CRP was elevated to 78 and the pancytopenia was persistent.

Microbiological examinations showed undergone Cytomegalovirus and Epstein Barr virus infections (positive IgG), while Parvovirus B19, Hepatitis B and C, and HIV were all negative. The analyzes were also negative for anti-streptolysin (AST), Treponema pallidum and interferon-gamma release assay (IGRA, an ELISA Quantiferon analysis) showed sensitization to M. tuberculosis but is unaffected by BCG vaccine or common atypical mycobacteria. This indicated that there was no streptococcal infection, syphilis or tuberculosis. There was no growth in blood cultures, and no findings of intestinal pathogenic bacteria or parasites in faeces. Hypergammaglobulinemia (IgG 28.2 g/L (1.3-6.6) could indicate a chronic inflammatory condition, while IgA and IgM were normal (1.2 g/L (0.1-1.3) and (0.8 g/L (0-1.8), respectively). On suspicion of spherocytosis due to anemia and organomegaly, blood samples were taken showing positive eosin 5-maleimide (EMA) test, and the condition could therefore be compatible with spherocytosis.

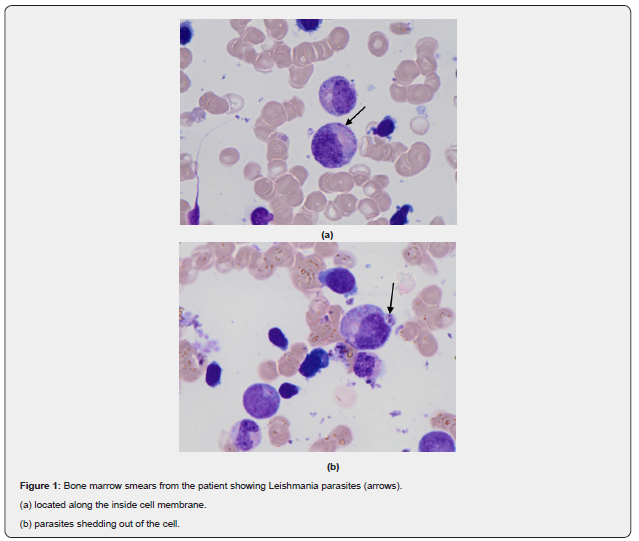

Since she and her family had visited Spain last summer, we assessed whether import fever and possible transmission during this stay could have caused the patient's condition. We checked for possible malaria disease due to the unclear disease picture and the periodic episodes of fever, but the girl had only stayed in Europe and the test was negative. We analyzed her bone marrow aspirate (Figure 1). Blood smears and now bone marrow showed no signs of malignancy. Blood and bone marrow specimens were also analyzed at the department of microbiology at Oslo University Hospital (OUS), with a request to analyze for import fever and neglectable infection diseases. This revealed a positive PCR in bone marrow for the parasite Leishmania, as well as findings of single-cell parasites by microscopy of blood and bone marrow aspirates. She was immediately put on liposomal Amphotericin B (3mg/kg) for 5 days. After 3 days, she was afebrile with improved general condition. After a week she was discharged home, and she received a final dose of Amphotericin 10 days after the 5-day treatment, at the out-patient clinic. At a follow-up check 2 months after discharge, the girl was well-functioning and healthy, and no longer anemic (Hb 11.9). There was a complete regression of her spleen and liver enlargement and she had not experienced episodes of fever after discharge.

Discussion

The 3-year old girl described in this report developed a severe form of visceral leishmaniasis (VL) with fever, anemia, hepatosplenomegaly, weight loss, and mild neurological symptoms. VL is a systemic disease that activates the blood-forming organs and the immune system and results in anemia and pancytopenia, hepatomegaly, splenomegaly and lymphadenopathy, and symptoms such as fever, weight loss, diarrhea, chills, anorexia and anemia [8]. Increasing anemia occurs due to progressive bone marrow failure, hemolysis and hypersplenism. Our patient had all of these symptoms, except for lymphadenopathy.

The case describes a protracted and atypical febrile illness. When her condition worsened, we suspected malignant disease or haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) secondary to an underlying infectious disease, autoimmune or rheumatic disease [1]. Infection associated HLH disease may be elicited by virus, bacteria, protozoa or fungi, and infection with Leishmania may be a relatively frequent triggering cause [9,10]. HLH secondary to visceral leishmaniasis has been reported very rarely and there are only few cases with imported visceral leishmaniasis in Norway and none described in children [11]. The diagnosis is made by the patient meeting a set of clinical and biochemical criteria, and for primary HLH by detecting a mutation consistent with the diagnosis [12,13]. HLH is characterized by fever, pancytopenia and hepatosplenomegaly, as well as neurological symptoms that are seen in up to a third of patients, but the clinical picture and severity varies [12,14]. This girl had fever, cytopenia, hepatosplenomegaly, and elevated ferritin blood levels and she gradually developed diffuse neurological symptoms with dizziness, lethargy and fatigue. We suspected infectious HLH in this patient with a clinically sepsis-like disease who did not respond as expected to presumed adequate antibiotics treatment. An important marker of HLH disease is a highly elevated serum ferritin value, often far higher than what is otherwise seen in acute phase reactions [15]. This corresponds to this case where the girl had 5-fold elevated ferritin levels. In the event of a deviating clinical course or lack of treatment response, ferritin is a useful and available variable that can be quickly answered. The girl gradually developed severe anemia (Hb 7.0) and the investigation revealed possible hereditary spherocytosis. This is one of the most common hemolytic anemia forms in Norway and is autosomal hereditary in most people. The girl did not have a family history of hereditary spherocytosis, nor was there any information about jaundice, which may be an early sign of spherocytosis. However, spherocytosis can have a varying clinical course, from almost asymptomatic to severe anemia.

A delayed anamnestic work-up revealed that the girl had visited southern Europe three months prior to being admitted to our hospital. The girl was born in Norway, and her mother is ethnically African. Last summer, 2 months before onset of symptoms, she and her family visited the highlands of Spain, but except for this, none of her contacts or she had visited countries in subtropical or tropical regions. The girl often played in the sandbox outside the summer house, and with animals, as there were many stray dogs as an in the area [16]. This information led to extended investigations for import fever and neglected diseases, which revealed leishmania parasites in her bone marrow and blood smears.

Visceral leishmaniasis is a so-called neglected tropical disease (NTD) that, if left untreated, can be fatal. It is gradually spreading to larger areas, partly due to increased travel activity and global warming [7]. In endemic areas sandflies are found primarily in the countryside, in sandbanks in river beds, in dry and semi-arid areas in mountain villages, underground rodent passages, scrub forests and rock piles, also in tropical forests [17]. The transmission of the parasite is either zoonotically, with an animal as an intermediate host, or anthroponotically via an insect vector to human. The route of transmission of leishmania in this case is likely through sandflies or dogs as an intermediate host. The parasite is spread by the bite of female sandflies and the incubation period can range from 10 days to 24 months and may last for several years, but is usually 2-6 months, which fits well with this case as she visited Spain about 3 months prior to appearance of symptoms [8,18]. Dogs are the main host in Europe, but other animals, including rodents, are also intermediate hosts [16,17,19]. After transfer from the insect vector, the parasite is taken up by macrophages where it is transformed from promastigot to amastigot, multiplies and spreads to the entire reticuloendothelial system. The infection can be asymptomatic, and with a weakened immune system the probability of a serious course increases [8,20,21], but an underlying immune deficiency was not seen as there were no signs of malignancy and she was HIV unexposed and negative. The gradually more severe anemia, persistently elevated CRP and pancytopenia, as well as hypergammaglobulinemia fits with a chronic hyperinflammatory condition seen in this case.

Visceral leishmaniasis is caused by either Leishmania donovani eller L infantum, the last is prevalent in Europe and Spain. The infection is characterized by a wide clinical spectrum, which may range from mild to moderate and severe clinical manifestations [22]. The disease usually has an insidious course, with gradual onset of lethargy, fever, weight loss and hepatosplenomegaly, [23] as in this girl. Later in the course, liver failure may develop with icterus and ascites This girl showed no hyperbilirubinemia or ascites. Liver failure and gradually worsening thrombocytopenia may also cause bleeding, but no bleeding tendency was observed in this girl. Kala-azar (black fever) is another name used for Leishmaniasis and refers to a darkening of the skin, but this was not seen here. Of notice, her mother was ethnically African which may have complicated skin color judgement, but we did not prove darkening of the girl´s skin during the disease process.

Leishmaniasis is distributed worldwide and 13 million people are estimated to be infected by this parasite, with about 1.8 million new cases each year. When it comes to VL, the World Health Organization calculates approx. 500,000 new cases and 50,000 deaths, annually, and the disease is on the rise in southern Europe [6,17,19]. The increase is associated with expanded travel activity, more people with weakened immune systems and an increasing impact area for host animals and vectors such as the plenty of sandflies in forests of northern Spain and central France, probably without any connection to climate change [2-4]. VL should be suspected in children who present with specific manifestations and the diagnosis should be established, mainly by the demonstration of leishmania in tissue specimens [7,20]. In the Norwegian context, the disease is most relevant for those who have symptoms and findings compatible with VL and have been to the Mediterranean or in more remote areas during the past year.

Conclusion

This case study emphasizes the importance of a thorough medical history, which must be seen in connection with the disease picture and the clinical findings. A complete travel history is required in case of obscure febrile illness after a stay in subtropical or tropical regions. Leishmaniasis is endemic in southern Europe, including popular tourist destinations such as the Mediterranean basin. It is relatively unknown to most medical practitioners in non-endemic areas, including Norway, and clinical vigilance is required to identify those who are infected.

Click here: https://juniperpublishers.com/index.php

No comments:

Post a Comment