Forensic Sciences & Criminal Investigation - Juniper Publishers

Abstract

Despite ongoing efforts to curb corporate fraud in both the public and private sectors, the prevalence of such fraudulent activity persists. Notably, digital forensics remains a primary focus of research, given its potential for facilitating fraud detection. In light of this, the study investigates the role of instant messaging forensics, specifically conversation data analytics, contact data analytics and unencrypted data analytics, in detecting corporate fraud within the Kenyan banking industry, guided by Locard’s Exchange Principal Theory. The research adopted a descriptive study design, which incorporated responses from a target population of 380 individuals, primarily from 43 banks and the banking fraud investigation department of the central bank. Our sample size encompassed 114 participants, out of which 100 provided responses through questionnaires and semi-structured instruments. The results indicate that that conversation data analytics (β= 0.308, p =0.001) and unencrypted data analytics (β= 0.226, p =0.003) have a significant positive impact on fraud detection in banks while contact data analytics (β= 0.016, p= 0.862) was found to have a non-significant effect on fraud detection. We recommend the that banks prioritize the adoption of conversation data analytics and unencrypted data analytics as a way to increase fraud detection in their systems.

Keywords: Digital forensics; Conversation data analytics; Contact Data analytics; Unencrypted data analytics; Fraud detection.

Introduction

The accelerating pace of technological and commercial advancements has coincided with a troubling surge in corporate fraud, posing significant challenges to the global financial sector and, specifically, the banking industry. High-profile surveys by leading consultancies and institutions such as the Association of Certified Fraud Examiners (ACFE), PricewaterhouseCoopers, Deloitte, KPMG, and Ernst & Young have underlined this escalating trend, capturing the attention and concern of businesses worldwide. The adverse implications of these fraudulent activities extend beyond destabilizing the banking sector; they also erode profitability, a concern that is especially pronounced in developing economies.

Across both developed and emerging markets, banks grapple with a spectrum of fraudulent activities that range from asset misappropriation to cybercrime, corruption, procurement fraud, and accounting inconsistencies [1]. These activities have been estimated to siphon off between 2% and 7% of banks’ annual revenue, translating to losses in the trillions of dollars on a global scale. This alarming trend necessitates deeper exploration, especially in the context of developing countries where existing research remains scant, Kassem (2014).

In an effort to fortify their defenses against this scourge of corporate fraud, banks globally have escalated their investments in strengthening internal controls and enhancing digital forensics investigation capabilities. The domain of Digital Forensic Investigation (DFI) has emerged as a linchpin in tackling digital crimes, encompassing a gamut of activities from the identification and preservation to the analysis, documentation, and presentation of digital evidence. As digital media increasingly becomes the de facto medium for storing and transmitting information, the significance of specialized forensic techniques in the fight against fraud amplifies, especially in developing countries where fraudulent activities are burgeoning [2]. This study pivots around the Kenyan banking sector, seeking to appraise the impact of instant messaging forensics investigations in detecting fraud. By scrutinizing various branches of instant messaging digital forensics, ranging from conversation data forensics, contact data analytics and unencrypted data forensics, this research aspires to elucidate the role these techniques play in mitigating corporate fraud within banks. The insights gleaned from this study will contribute to the formulation of more efficacious fraud detection and prevention strategies, thereby enhancing financial stability and preserving the profitability of banks.

Literature Review

Theoretical framework

The Locard Exchange Principle (LEP), established by Edmond Locard (1877–1966), the founder of the Lyons Police Technical Laboratory in France, serves as the foundational theory for this study. LEP asserts that every interaction or contact between two entities results in an exchange of trace evidence [3]. This principle has been extended to digital crime investigations, where digital evidence, such as logs or malware, may be present even in the absence of physical contact between the perpetrator and the crime scene [4]. LEP provides a robust theoretical basis for the study’s objectives, as it suggests that traces of digital evidence can be found and analyzed in various forms of digital forensic investigations. LEP posits that digital evidence, such as messages exchanged between fraudsters, can be uncovered through instant messaging forensic investigations, leading to the identification of perpetrators and their criminal activities [5]. The theory also implies that traces of digital evidence may be present on social media platforms used by fraudsters, allowing for the identification and analysis of criminal activities through social media forensic investigations [6]. LEP supports the idea that computer systems and networks can contain digital evidence, such as malware or logs, which can be analyzed through computer forensic investigations to detect and deter corporate fraud [4]. In addition, the theory suggests that mobile devices, which have become indispensable tools for fraudsters, may contain retrievable digital evidence that can be analyzed through mobile forensic investigations to identify and counter corporate fraud [5]. Locard Exchange Principle serves as a valuable theoretical underpinning for this study, emphasizing the significance of digital evidence in combating corporate fraud. By applying LEP to the context of digital forensic investigations in the Kenyan banking industry, this study aimed to contribute to a deeper understanding of the roles played by various forensic methods in detecting and preventing corporate fraud.

Literature review

Instant messaging forensics and fraud detection in banks: Instant messaging, a form of real-time communication enabling private conversations via the internet, has gained significant popularity since its inception in 1996 with the launch of the ‘I Seek You’ service. The evolution of instant messaging has extended beyond text-based conversations to include the exchange of various media formats, location sharing, and voice and video calls. This widespread adoption has led to the incorporation of instant messaging in businesses, organizations, and government agencies worldwide, exemplified by services such as WhatsApp Business Chat and Twitter accounts of government officials. Given the ubiquity of instant messaging, it is crucial for forensic investigators to analyze conversation artifacts during device examinations. Décary-Hétu and Aldridge [4] highlighted the importance of instant messaging forensics in digital crime investigations, but their study did not specifically address its role in various industries such as banking. Previous research on instant messaging forensics has primarily focused on popular applications for Android and iOS mobile operating systems. Studies by Gao and Zhang (2013) and Ovens and Morison (2016) have explored artifacts left by applications such as WeChat and Kik on iOS devices. However, these studies largely centered on the first generation of instant messaging apps, neglecting the latest generation of platforms like WhatsApp and Telegram. While Sgaras et al. (2015) conducted a forensic acquisition and analysis of WhatsApp, Viber, Skype, and Tango on both Android and iOS, their focus was on evidence acquisition in digital forensic investigations rather than evidence assessment and examination processes. Stirparo (2016) examined general iOS forensics information and investigated the security features of Telegram, Signal, and WhatsApp, corroborating Sgaras et al.’s (2015) findings on WhatsApp’s unencrypted Chat Storage SQLite database on iOS. Rathi et al. (2018) analyzed forensic artifacts left by WeChat, Telegram, Viber, and WhatsApp on Android smartphones, revealing methods for retrieving encrypted databases and decrypting them. However, these studies do not explicitly explore the role of instant messaging forensics in detecting corporate fraud [7-10]. One of the most promising areas in instant messaging forensics is conversation data analytics, which involves the algorithmic analysis of textual and non-textual elements within chat conversations. Kim and Lee (2016) were among the pioneers to integrate natural language processing (NLP) tools into fraud detection, highlighting the potential of keyword frequency as a predictor of fraudulent intent. Johnson and Gupta (2018) took this a step further by employing machine learning algorithms to categorize patterns of conversation that correlate with fraudulent activities. Their study, however, raised questions about the use of conversation data analytics in various sectors outside policing sector, a concern later echoed by Davis and Williams (2019).

But while these studies showed promising outcomes, they also revealed significant gaps in the field. For instance, Smith et al. (2017) pointed out the absence of standardized protocols for analyzing conversation data. They noted that the forensic community has yet to agree on the metrics and tools to be used, creating inconsistencies in the quality and reliability of the findings. Moreover, the issue of false positives and negatives was raised by Thompson and Smith (2020), who found that current algorithms could erroneously flag innocuous conversations as suspicious. Another critical aspect of instant messaging forensics is the analysis of unencrypted data. Because they are not protected by cryptographic algorithms, unencrypted messages and files are easier to intercept and scrutinize. Williams (2016) provided empirical evidence suggesting that unencrypted data often yield quicker results in fraud investigations due to the reduced need for decryption. Davis et al. (2017) supported this view by empirically showing that the absence of encryption not only facilitates faster analysis but also increases the accuracy of the results. However, the ethical implications of this approach have been a significant concern. Brown and George (2018) delved into the ethical dimensions of scrutinizing unencrypted data, especially where third parties are involved. They argued that the ease of access to such data raises questions about privacy and consent, issues that the forensic community has yet to fully resolve. Furthermore, Yang and Zhang (2019) noted that with the growing adoption of end-to-end encryption in corporate communications, the future relevance of unencrypted data analytics is becoming increasingly uncertain [11-16].

The final component under review is contact data analytics, which focuses on analyzing an individual’s network of contacts within the instant messaging environment. Zhang et al. (2015) were among the first to illustrate the effectiveness of this approach in identifying fraudulent networks within organizations. Their empirical study used basic statistical methods to map out contact frequencies and durations, thereby identifying potential key players in fraudulent activities. This methodology was later refined by Thompson and Smith (2020), who integrated machine learning algorithms to reduce false positives and negatives. However, despite these advancements, the field of contact data analytics still has significant gaps. For example, Yang et al. (2021) pointed out that existing methodologies are prone to generating false positives, which can have severe legal consequences. Additionally, the ethical aspects of contact data analytics remain underexplored. Questions about data ownership, consent, and the potential for misuse are yet to be adequately addressed, as noted by Wilson and Davis (2020). The empirical literature on the role of instant messaging forensic investigations in the detection of corporate fraud reveals several critical gaps that warrant further study, particularly within the context of commercial banks in Kenya. First, there is a pressing need for testing the applicability of instant messaging forensics in various contexts using the developed standardized protocols and methodologies. Existing research highlights the inconsistency in the tools and metrics employed, leading to variable quality and reliability in outcomes. Second, ethical concerns, especially concerning unencrypted and contact data analytics, remain largely unaddressed. These ethical dilemmas become more pressing in a banking environment where confidentiality and privacy are paramount. Third, the legal admissibility of evidence generated from instant messaging forensics is still a grey area, a critical concern in the prosecution of fraud cases. Fourth, the rapid adoption of encryption technologies raises questions about the future utility of certain types of data analytics, particularly unencrypted data analytics. Lastly, there is a notable lack of comprehensive methodologies capable of minimizing false positives and negatives, an issue that could result in wrongful accusations or overlooked fraudulent activities. Given that commercial banks are integral to Kenya’s economy and are susceptible to sophisticated fraudulent schemes, addressing these gaps becomes vital for enhancing the effectiveness and reliability of fraud detection mechanisms within this sector [17-25].

Materials and Methods

Study design

This research employed a descriptive design to investigate the role of instant messaging forensics in detecting corporate fraud within the Kenyan banking sector. The study encompassed 43 Kenyan banks and also included the Banking Fraud Investigation Department (BFID) at the Central Bank of Kenya (CBK). The target population consisted of 390 individuals, specifically digital forensics managers and officers working within these banks and the BFID, all of whom are directly involved in handling cases of corporate fraud requiring digital forensic investigation.

Sampling methodology

A total sample size of 114 digital forensic officers, representing both the banks and the Central Bank of Kenya, was selected for this study. Stratified proportionate sampling techniques were used to divide respondents into two categories: officers and managers from both the banks and BFID. In addition, purposive sampling was used to select participants with specific expertise in digital forensics within these institutions. To address the study’s sensitive nature and encourage participation, a snowballing technique was employed, leveraging existing relationships and referrals to gain the trust and cooperation of prospective respondents [26-34].

Data collection instruments and procedure

Data collection relied exclusively on a Likert-type questionnaire, composed of 5-point scale questions, aimed at gathering insights on various facets of instant messaging forensics, including conversation data analytics, contact data analytics, unencrypted analytics, as well as fraud detection in banks. Questionnaires were distributed and administered through a combination of drop-and-pick methods and face-to-face interviews. The latter were also employed for conducting semistructured interviews. To ensure the instrument’s reliability and validity, a pilot study was conducted involving 11 respondents from the Criminal Investigation Department’s fraud investigation unit. Content validity was ascertained by incorporating questions directly related to the constructs being measured, while face validity was enhanced through consultations with subject matter experts and academic supervisors. The internal consistency of the questionnaire was evaluated using Cronbach’s alpha test.

Data analysis

Completed questionnaires were coded and entered into SPSS software (version 24) for analysis. Given the use of close-ended questions, data entry was streamlined and efficient. Data was first cleaned and coded, followed by descriptive statistical analysis using frequencies and percentages to summarize respondent profiles. Multiple regression techniques were employed to assess the relationship between digital forensics methods and fraud detection, thereby testing the study’s objectives [35-40].

Results

Respondent profiles in terms of work experience

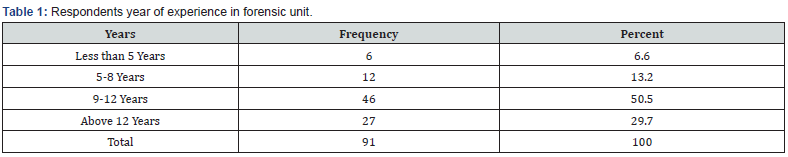

Table 1 results shows that about half of the respondents (50.5%) have between 9 to 12 years forensic investigation experience followed by those who had more than 12 years of experience (29.7%). 13.2% of the respondents had between 5- 8 years of experience while 6.6% had less than 5 experience. These results imply that significant portion of the respondents had experience on forensic investigation.

Regression results

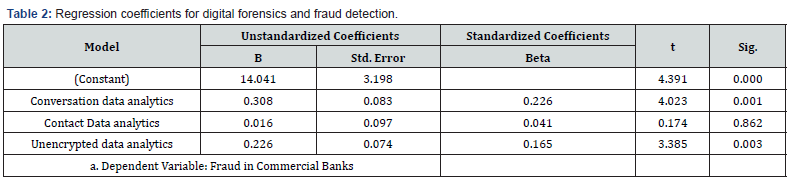

The results in table 2 shows the relationship between digital forensics technologies and fraud detection in banks. The dependent variable is fraud detection in banks, while the independent variables are conversation data analytics, contact data analytics and unencrypted data analytics. The results indicate that conversation data analytics (p =0.001) and unencrypted data analytics (p =0.003) have a significant positive impact on fraud detection in banks. On the same note, conversation data analytics has the highest contribution (β= 0.308) to fraud detection followed by unencrypted data analytics (β= 0.226) and contact data analytics (β= 0.016) [41-45].

Discussion of Findings

The study found that conversation data analytics has a significantly positive impact on fraud detection in banks, as indicated by a p-value of 0.001 and a beta coefficient of 0.308. This result aligns with previous scholarly work, such as the study by Johnson and Gupta (2018), which found that machine learning algorithms could effectively categorize patterns of fraudulent conversations. The strong beta coefficient of 0.308 suggests that among the variables studied, conversation data analytics is the most potent predictor of successful fraud detection. The study also revealed that unencrypted data analytics has a significant positive impact on fraud detection, with a p-value of 0.003 and β=0.226. This supports Davis et al. (2017), who noted that unencrypted data often yield quicker and more accurate results in fraud investigations. The result also underscores the importance of unencrypted data analytics in the banking sector, suggesting that it is a valuable but slightly less influential tool compared to conversation data analytics for combating fraud. Contrary to expectations, contact data analytics showed a very minimal impact on fraud detection in banks, with a β value of 0.016. This is surprising given prior research, such as the study by Zhang et al. (2015), which found contact data analytics useful in identifying fraudulent networks within organizations. The unexpected result in our study raises the question of whether the role of contact data analytics in fraud detection is context-dependent or influenced by other variables not considered in this study.

Conclusion

The current study provides an understanding of the role of instant messaging forensics investigation on fraud detection within commercial banks, particularly focusing on the Kenyan context. Our empirical findings indicate a significant positive relationship between conversation data analytics and fraud detection. Similarly, unencrypted data analytics also emerged as a significant predictor of successful fraud detection, albeit to a lesser extent. Surprisingly, contact data analytics demonstrated a minimal impact. These findings offer both academic and practical implications. From an academic standpoint, the study validates the significance of conversation and unencrypted data analytics in fraud detection, while raising questions about the role of contact data analytics that warrant further investigation. Practically, the results suggest that commercial banks in Kenya would benefit from investing more heavily in conversation and unencrypted data analytics technologies for more effective fraud detection. Given the increasing sophistication of fraud schemes, adopting such advanced forensic methods appears to be not just beneficial but essential for ensuring the financial integrity of banks.

To Know more about Journal of Forensic Sciences & Criminal Investigation

Click here: https://juniperpublishers.com/jfsci/index.php

To Know more about our Juniper Publishers

Click here: https://juniperpublishers.com/index.php

No comments:

Post a Comment