Online Journal of Public Health - Juniper Publishers

Abstract

Background

Frailty is a geriatric syndrome of increased vulnerability due to diminished physiologic reserves. It is still unclear how the psychosocial factors and physical frailty are related to health outcomes. This study presents prevalence, related physical and psychosocial factors of frailty in older adults in Singapore and the mediation effect of frailty among psychosocial factors.

Methods

Using a cross-sectional analysis of 491 individuals over 65 years of age from 17 community centers, frailty conditions were grouped as Robust, Prefrail and Frail. Psychosocial profiles were collected through established Depression, Social Support, Quality of Life and Loneliness scales.

Results

Approximately 60.4% of the participants were between 65 and 74 years of age and 70.3% were women with 3.3% and 37.1% of participants rated as frail and pre-frail, respectively. Results indicated that depression, loneliness, and fall efficacy were significantly lower while social support and quality of life higher in the robust participants compared to prefrail and frail participants. Pathway analyses examined the mediation effect of frailty from psychosocial factors (depression, loneliness, social support) to quality of life. Depression had direct significant association with both frailty (B = 0.034, p <.001) and quality of life (B = -0.497, p <.001).

Conclusions

Frailty has been validated as a mediator on the pathway from psychosocial conditions to health. Psychosocial interventions should be considered further to reduce frailty and improve quality of life. Longitudinal research combining both physical and psychosocial factors are promising to explore the pathways to frailty and its adverse health outcomes.

Keywords: Frailty; Psychosocial Factors; Depression; Social Support; Loneliness; Pathway Analysis

Introduction

Worldwide and in Singapore, the population is ageing. Until now, Singapore’s older adults (aged 65 years and above) constitute 15.2% of the total population [1]. This is expected to be 53.4% in 2050 [2]. Frailty is a condition in which the individual is in a vulnerable state at increased risk of adverse health outcomes and/or dying when exposed to a stressor [3]. It is usually recognized in older adults and leads to adverse health effects [4,5]. Frail people have a significantly higher risk of falls, disability, long-term care and even leading to death [6,7]. In a report which reviewed 21 community-based cohort studies of 61,500 elderly people, the prevalence rate of frailty among older adults aged 65 or more is 9.9% [8]. Global data from more than 120,000 senior citizens of 28 countries suggests a 43.4% frailty incidence rate [9]. While it is generally believed that frailty increases with age, no consensus has been reached on the prevalence of frailty [8]. Singapore is a global business hub with 4.04 million residents, and the median age of the resident population rise to reach 41.5 years [1]. It is also one of the fastest ageing nations in the world. The old-age support ratio of residents computed as the ratio of residents aged 20-64 years for each resident aged 65 years and over, declined further to 4.3% until 2020 [1]. One of the most urgent ageing issues to address is frailty [10]. That is, high prevalence among older adults and increased risk of adverse health outcomes such as falls, disability, depression, hospitalization, medical costs, and mortality [4,11-14]. Singapore’s government has responded to the ongoing frailty movement [15]. In the past decade, many studies have examined the association between frailty and socio-demographic factors. However, few studies focus on the psychosocial factors and their impact on frailty prevalence in Singapore [13,15-17]. highlighted the need to investigate the psychosocial factors impacting frailty in older adults, vital to addressing the health and well-being of the rapidly ageing population in Singapore.

Many studies have tried to explain the mediators and moderators within the pathway of frailty and health outcome [18-20, 21] developed a working framework to elaborate the pathway from frailty to its adverse outcomes. In the meantime, [22]. and [18] also elaborated those psychosocial factors in a general matter for health and wellbeing. There are numerous research studies that investigated factors such as: (i) depression being associated with a higher risk of frailty [23-25]. and (ii) living alone lacking in social support and socially isolated had a higher risk of developing frailty [26-28]. Recent findings suggest being older, female, living alone, lacking regular exercise and poor health status are significantly associated with frailty prevalence [29-31] suggested the presence of adverse health outcomes, poor cognition, polypharmacy, sarcopenia, fall rate, living in a private institution or hospital and mortality are related to frailty. Similar findings are supported by [32]. where physiological issues such as poor weight management, disease, and poor psychological health contribute to frailty. Hence, according to Berkman’s model [18] and the frailty pathway framework [21]. we examined the existing pathway model on the effects of psychosocial factors on frailty and health outcomes among community-dwelling older adults. In a summary, using Singapore as a case example, the study aimed to investigate the prevalence and related psychosocial factors of frailty in older adults in Singapore and the main research question is: RQ: What are association between psychosocial factors and frailty and mediate role of frailty between psychosocial factors and Quality of Life (QoL)?

Methodology

Study design

This was a cross-sectional study using convenience sampling. Participants underwent a screening phase and a psychosocial profiling phase to gather pre-study data. In the screening phase, upon providing informed consent to take part in the study, participants were issued a questionnaire to gather their basic demographic information and proceeded with the screening session, in which participants were assessed using the frailty scale (Five-item Frail Scale) from [33]. In which the ratings were used to identify the state of frailty in the participants: non-frail (0); pre-frail (1-2); and frail (3-5). Frail participants did not proceed with physical performance assessments. Other self-reported questionnaires include the Katz Activities for Daily Living (ADLs) [34]. and Lawton’s Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADLs) [35]. as well as a Fall Efficacy Scale [36], were used. Other biomechanical/physical performance data were collected using the Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB) [37]. Gait Speed [38]. One-Leg Stand and Grip Strength [33]. In the psychosocial profiling phase, an interviewer-administered questionnaire consisting of validated scales were used to gather data pertaining to participants’ psychosocial conditions to measure Depression, Social Support, Quality of Life, and Loneliness (Table 1). Trained personnel (who had undergone training by research staff/occupational therapist/physiotherapists) conducted the various physical performance assessment components. The study was a single research visit per participant. The entire process took approximately 1 hour per participant.

Measurements

5-Item frail scale

The FRAIL scale included 5 components: Fatigue; Resistance; Ambulation; Illness; and Loss of Weight. Frail scale score ranged from 0-5 (i.e., 1 point for each component; 0=best to 5=worst) and represented frail (3-5), pre-frail (1-2), and robust (0) health status.

Katz activities of daily living (ADLs)

Basic ADLs included seven items (bathing, dressing, eating, transferring bed or chair, walking across a room, getting outside, and using the toilet).

Lawton instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs)

IADLs included eight items (preparing meals, shopping for groceries, managing money, making phone calls, doing light housework, doing heavy housework, getting to places outside walking distance, and managing medications).

Short physical performance battery (SPPB)

The SPPB is a summary measure of lower body performance based on three-component tasks: standing balance; chairs stand; and usual walking speed. Each component task was scored as 0-4 (range 0=worst to 4 best), and a composite score was computed as the sum of scores on component tasks as 0-12 (range 0=worst to 12=best).

Gait speed

Gait speed was assessed in respondents’ homes using a standardized 4-meter course with participants instructed to walk at their usual pace. The average walking speed (meters/second) was computed for two trials.

One-leg stand

For the one-leg stand test, individuals chose their preferred leg to balance on and were required to raise the other foot at least 2 inches above the ground and hold the position for as long as possible up to 30 seconds.

Grip strength

Isometric grip strength was assessed using a digital handgrip dynamometer. The mean of the last two maximal effort trials were used in the analysis. The test was performed seated in a chair (without armrests), with feet flat on the floor and the other arm held flat against the side with the elbow at 90°.

Falls efficacy scale

The Falls Efficacy Scale (FES) measures confidence in performing 10 everyday activities without falling. The response for each FES item ranges from 0 (no confidence) to 10 (complete confidence) and the FES total score ranges from 0-100.

Depression

The Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) included 20 items comprising 6 scales reflecting major dimensions of depression [39]. depressed mood; feelings of guilt and worthlessness; feelings of helplessness and hopelessness; psychomotor retardation; loss of appetite; and sleep disturbance. It measured self-reported symptoms associated with depression experienced in the past week. Higher scores represent more depressive symptoms. A cut-off score of 16 indicates high depressive symptoms.

4 Social support

The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) measured how much support a person feels he or she gets from family, friends, and significant others [40]. The items tended to divide into factor groups relating to the family (FAM), friends (FRI) or significant others (SO). (1=very strongly disagree, 2=strongly disagree; 3=mildly disagree; 4=neutral; 5=mildly agree; 6=strongly agree; 7=very strongly agree).

4 Quality of life

The EQ-5D-5L is a standardized instrument to measure generic health status [41]. It is made up of two components: health state description and evaluation. The health state description contained 5 dimensions with 5 response levels (no, slight, moderate, severe, or extreme). The evaluation part measured respondents’ overall health status on a visual analog scale (VAS).

4 Loneliness

This scale evaluated feelings of loneliness in individuals. An 8-item short form using a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 1, never, to 4, always. Minimum and maximum possible scores are 8 and 32, respectively. Higher scores from USL-8 corresponded to severe loneliness. A cut-off score of 24 was used to classify lonely and not lonely participants based on a previous study [42].

Data Collection

We conducted a survey study on the target population to identify frailty conditions and psychosocial profiles among older adults in Singapore. A total of 491 community-dwelling older adults were recruited from 17 Senior Activity Centers (SACs) / Voluntary Welfare Organizations (VWOs) in Singapore from March to September 2018. The inclusion criteria were: (i) Age >= 65 years (WHO, 2013); (ii) No significant cognitive deficits and can understand and follow instructions; (iii) No significant physical impairments and community ambulant; and (iv) Living in the community and not in a nursing home.

Results & Analyses

Calculations were made using the SPSS IBM 25.0 software. A chi-square (2) analysis was performed for intergroup sociodemographic and categorical data. Independent t-tests and analysis of variances were used on continuous data. Kruskal-Wallis H test was used when assumptions of normality and/or homogeneity was/were violated. Multiple regression was carried out with frailty score and quality of life as dependent variables. In all hypotheses, a significance level of α=0.05 was used, and a confidence interval of 95 % was accepted for statistical significance (p<0.05) at a 2-tailed level.

Demographics

A total of 491 eligible older adults took part in the study. The average age of the participants was (M=74.23, SD=6.25) and 127 were males. Socio-demographic findings showed that majority of the study participants were in the age group of 65-74 years (54.6%) in three major ethnic groups of Chinese (87.58%), Malay (8.96%) and Indian ethnic group (3.46%). Of the 491 participants, 6.52% were ascribed to tertiary education, unemployed (never worked and not working) (89.82%), married (56.1%) and living with family members (70.06%). The variables measuring health status showed that 39.31% of the study participants had at least two chronic conditions (the combination of hypertension, cardiovascular disease, arthritis, respiratory disease etc.) and 10.79% had depressive symptoms. About 3.46% reported feelings of loneliness.

Here are three findings:

Prevalence of frailty among community-dwelling older adults (65 years and above)

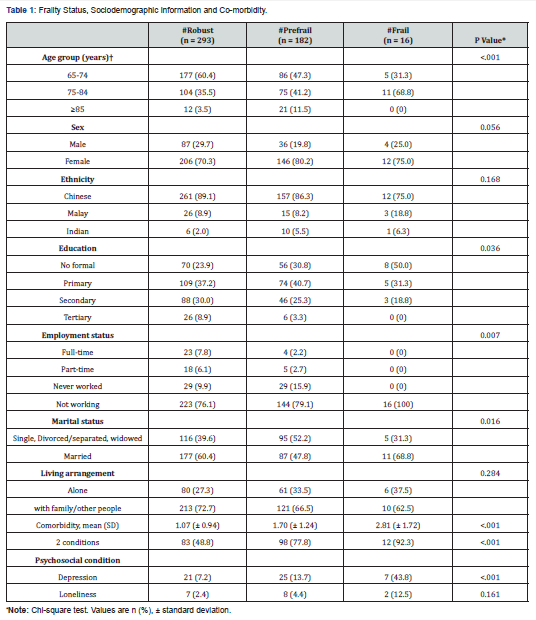

The prevalence of frailty among community-dwelling older adults aged 65 years old and above in Singapore was at 3.3%. Approximately 37.1% and 59.7% were identified as pre-frail and robust respectively. The socio-demographic information associated with frailty is shown in (Table 1). The prevalence of frailty increased significantly with age, p <.001 among those aged 60-74 years and 75 years and above, from 31.3% to 68.8% respectively. There was a higher prevalence of frailty among females, with marginal significance, p=.056. Among ethnic groups, a larger proportion of Chinese was robust as compared to the Malay and Indian ethnic groups. While ethnicity was not significantly associated with frailty status, it is interesting to note that the Indians had a higher proportion of pre-frails at 58.82% compared to those in robust, 35.29%. Education was significantly different across frailty status, p=.036. Half of the frail participants had no formal education followed by 31.3% and 18.1% in primary education and secondary education respectively. Employment status was significantly associated with frailty status, p=.007, where 100% of frail participants were not working. There was a higher proportion of married people who were robust (60.4%) compared to those who were single, divorced/separated, widowed (39.4%). Interestingly, more people were frail in the “Married” (68.8%) than “those otherwise/not married” categories (31.3%). A higher proportion of those who lived alone was frail (37.5%) than prefrail (33.5%) and robust (27.3%) (Table 2).

Association among frailty, functional status, fall efficacy, physical performance, psychosocial well-being, and health-related quality of life

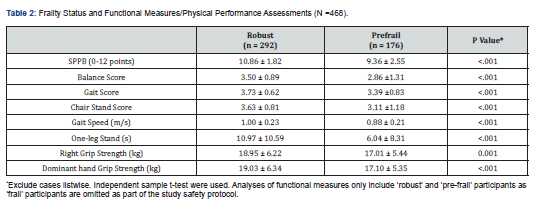

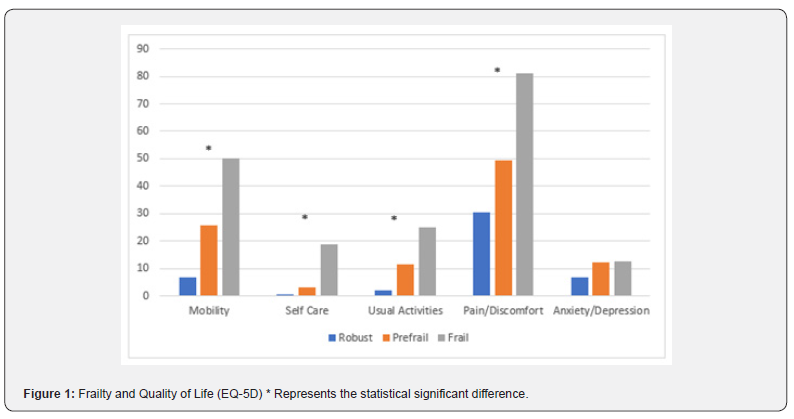

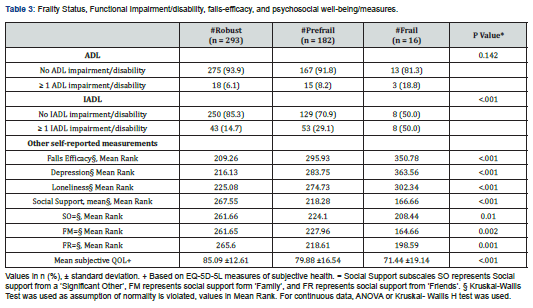

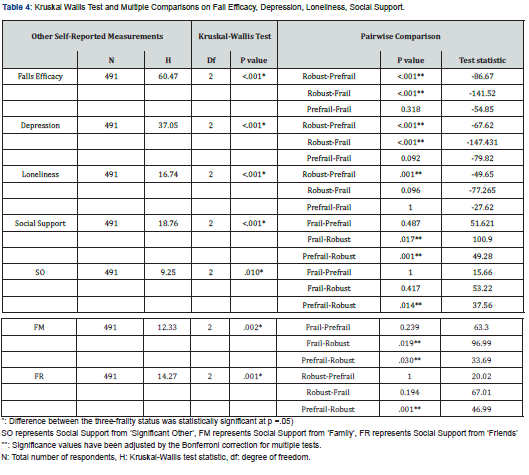

There was a significant difference in IADL functional status, where p < .001 but not ADL functional status. As frailty status progresses from robust to frail, the proportion of older adults with ADL/IAD impairment increases as shown in (Table 3). Significant differences were also seen in Fall efficacy where frail participants had higher mean rank scores compared to prefrail and robust participants (Table 3). Pairwise comparison comparing the three-frailty status be found in (Table 4). Physical performance measures were compared between robust and prefrail participants. Significant differences in physical performance measures between the two groups, p <.001 (Table 2). Robust participants had significantly higher SPPB scores, higher gait speed, better performance in one-leg stand time, and stronger dominant handgrip strength than those in prefrail, p <.001. Hence, for the second research question, we conclude that IADL functional status, fall efficacy and Physical performance are significantly associating with frailty. A significantly higher proportion of frail (43.8%) participants depressed/have high depressive symptoms than prefrail (13.7%) and robust (7.2%) participants, where p <.001. However, there was no significant difference in the proportion of participants who were lonely across frailty status. Significant differences were observed in loneliness and depression scores across frailty status, p < .001 (Table 2). Loneliness score was significantly higher in both prefrail and frail participants than robust participants, where p =.001. Robust participants had a significantly lower score depression score than prefrail and frail participants respectively, p <.001. Kruskal-Wallis H tests showed that there was a significant difference in overall social support between the different frailty status, χ2(2) = 18.76, p < .001. Multiple Pairwise comparisons showed that robust participants were significantly higher than frail participants (Mean Rank = 166.66), p =.017, and robust participants (Mean Rank =267.55) were significantly higher than pre-frail participants (Mean Rank = 218.28), p =.001. Social support from the subscales from friends (FR), family (FM), and a significant other (SO) was also found to be significant. Multiple pairwise comparisons results can be found in (Table 4). We measured frailty with health-related quality of life. Self-reported health status was significantly lower in frail, followed by prefrail, and robust participants (Table 3). Frailty was significantly associated with having problems in all domains of health dimensions where robust participants had the least problems except in anxiety/depression. (Figure 1) shows the percentage/proportion of frail, prefrail, and robust participants who had problems with all five health domains (EQ-5D). The top two domains frail participants had problems with were pain/discomfort (81.3%) and mobility (50%). Self-evaluated overall health status was significantly lower in frail participants followed by prefrail and robust (Table 3). Findings showed that factors affecting psychosocial well-being and health-related quality of life are significantly associated with frailty.

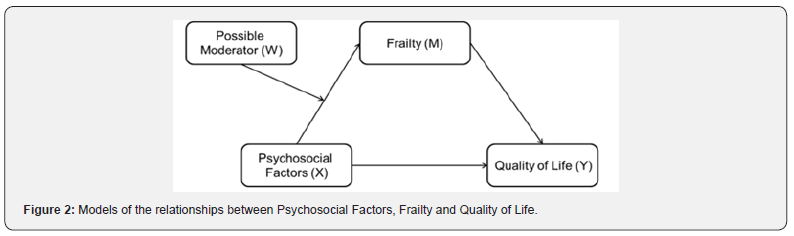

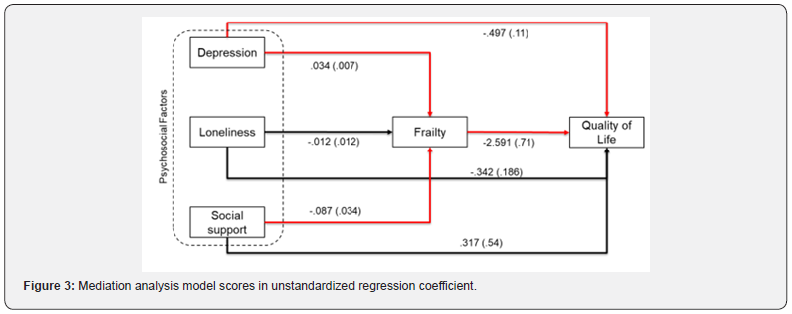

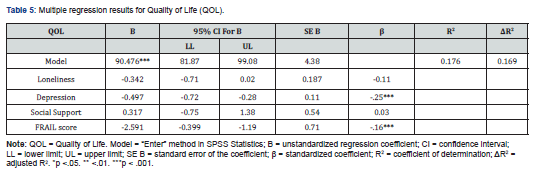

Validation of the mediation effect of frailty through pathway analyses

Based on the existing pathway models [19-21]. We selected the existing model linking psychosocial factors (X) to quality of life (Y), which is conditional if the indirect effect of X on Y through M (a mediator variable) depends on W (a moderator variable) (Figure 2). To validate the mediation effect of frailty among psychosocial factors and quality of life, two regression models to obtain the path coefficients to determine whether independent variables like depression, loneliness, social support, and frailty scores would significantly predict the quality of life, the outcome dependent variable. Multiple regression was run to predict the quality of life from loneliness, depression, social support, and frail scores. The multiple regression model statistically significantly predicted quality of life, F (4,485) = 25.891, p < .001, adj. R2 = .176. All variables added statistically significantly to the prediction, p < .05 except for social support, p = .558 and loneliness, p = .066. Regression coefficients and standard errors can be found in (Table 5). (Figure 3) shows the frailty mediational hypothesis model from psychosocial factors to quality of life. The red and black lines represent the significant and non-significant relationships. A cumulative odds ordinal logistic regression with proportional odds was run to determine whether depression, loneliness and social support affect the frail scores. A decrease in social support was associated with an increase in the odds of higher frail scores, with an odds ratio of .832 (95% CI, .711 to .972), Wald χ2(1) = 5.369, p = .020. An increase in depression scores was associated with an increase in the odds of higher frail scores, with an odds ratio of 1.071 (95% CI, 1.037 to 1.105), Wald χ2(1) = 17.814, p < .0005. A decrease in loneliness was not associated with an increase in the odds of higher frail scores, with an odds ratio of .982 (95% CI, .930 to 1.036), Wald χ2(1) = .444, p = .505. These results supported the existing mediational hypothesis model, which revealed that the indirect effect of depression, loneliness, and social support on quality of life was mediated by frailty. Depression had both direct and indirect impacts on quality of life.

Discussion

This study investigated the prevalence of frailty among community older adults (65 years and above) in Singapore. Based on our findings, the prevalence of frailty (3.3%) is similar to earlier study conducted from 2010 to 2013 in Singapore [16,17]. Compared to other countries where the prevalence of frailty ranged from 4% to 44% [8]. The prevalence of frailty among the older adults in Singapore is at the lower end of the spectrum at 3.3%, and early interventions at personal, community and societal levels are needed before the problem becomes serious. Results also revealed that the prevalence of frail and pre-frail states increased with age, which is in line with the general literature [8]. The study also showed that approximately 31.3% of those aged 60-75 years were frail, showing the importance of assessing frailty even among those aged <60 years. We observed ethnic differences in pre-frailty and frailty, concurring with findings from a study by [16]. Singapore primarily has three main ethnic groups, namely, Chinese (74.3%); Malays (13.5%); Indians (9.0%) [1]. Chinese older adults were found to have a lower prevalence of both frailty (2.79%) and pre-frailty (36.5%) at the bivariate level, compared to Indian older adults who were found to have almost twice the odds for frailty (5.88%) and pre-frailty (58.82%) (Table 1). However, Malay older adults have a prevalence of frailty (6.82%) and pre-frailty (34.09%). [43] and [44] pointed out that frailty is more prevalent in ethnic minorities, as cultural factors, and lifestyle choices in turn lead to variations in health habits and access to resources. Older adults may benefit from the multicultural society and environment in Singapore, hence the prevalent difference between the ethnic group is not significant. More longitudinal studies to understand relationships between frailty and social support are pertinent in formulating customized intervention programs for the different ethnic groups in Singapore.

While many studies have already done on predictors of physical frailty in older people, less is known on psychosocial factors for whom and how they exert their effects. Based on the Bergman conceptual framework and possible model identified recently [19,21]. The adopted conditional process model is the indirect effect of depression, loneliness, and social support on Quality of Life through frailty that is moderated (Figure 2). Observing associations between quality of life and conditions measured concurrently does not necessarily permit understanding of the direction of effect. Rather, these associations describe how Quality of Life levels vary with a broad set of psychological conditions in older people. Based on our findings, frailty is one mediator among the psychosocial factors to Quality of Life, while age, gender, ethnicity, education, employment, and marital status are possible moderators on pathways from psychological conditions to Quality of Life.

Conclusion

As a summary, establishing frailty prevalence and its related psychosocial factors is undoubtedly important for both clinical practice and the national healthcare system. According to our study results, the prevalence of frailty and pre-frailty are 3.3% and 37.1%; the results also investigated the association between psychosocial factors and frailty and mediate role of frailty between psychosocial factors and Quality of Life. The study has several clinical, research, and policy implications. Though sampling participants and periods are limited, the psychosocial factors impacting frailty may be underestimated. Preliminary findings have shown the factors (social support, depression, loneliness and fall efficacy) associated with frailty and pre-frailty which require a need for greater collaboration between health professionals, social services and researchers concerned with the health and well-being of older adults in the community. This study’s findings confirmed that depression, loneliness, and social support have direct and indirect impacts on quality of life. Hence, a good social functioning with the meaningful networked community is important as it nudges healthy ageing and reduced vulnerability [45]. And loneliness.

To Know more about Juniper Online Journal of Public Health

Click here: https://juniperpublishers.com/jojph/index.php

To Know more about our Juniper Publishers

Click here: https://juniperpublishers.com/index.php

No comments:

Post a Comment