Psychology and Behavioral Science- Juniper Publishers

Abstract

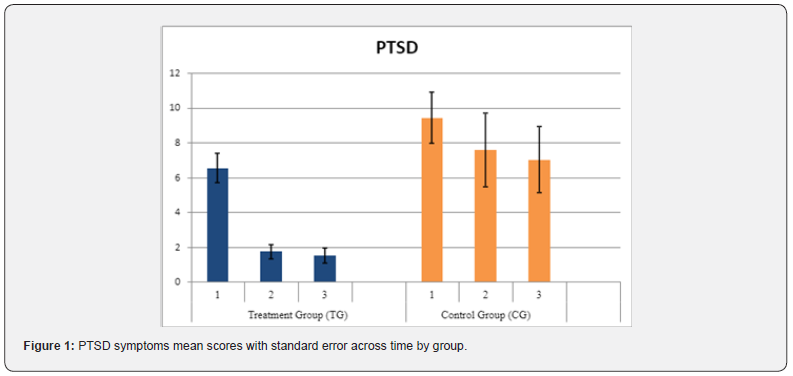

This clinical controlled trial had two objectives: 1) to evaluate the effectiveness, efficacy, and safety of the Healing Drawing Procedure (HDP) group trauma treatment intervention in reducing posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms among vulnerable children living in Taraz, Kazakhstan and 2) to explore the effectiveness and safety of non-specialist mental health providers (MHPs) being trained in and delivering the HDP group trauma treatment intervention as part of the task-sharing focused Trauma Healing Training Program (THTP), which is being developed to safely bring effective mental health treatment interventions to high-need, low-resource contexts, specifically in low-and-middle-income countries (LMICs). A total of 22 children between the ages of 7-14 (M = 10.09 years old) met the inclusion criteria and participated in the study. To evaluate the effectiveness, efficacy, and safety of the HDP treatment intervention in reducing PTSD symptoms in vulnerable children, repeated-measures ANOVA was applied, comparing the Treatment Group (TG) and the Control Group (CG). Results showed that the HDP treatment intervention had a significant effect for time, with a medium effect size (F (2,40) = 17.72 p <.000, η² = 470), and a significant effect for group with a lower effect size (F (1, 20 = 76.66, p<.001, η² = .404). Intragroup comparisons of means showed significant differences for the Treatment Group (TG) between Time 1. Pre-test assessment and Time 2. Post-treatment assessment with a large effect, t (14) = 5.42, p=.00, d = .955. These data confirm the effectiveness, efficacy, and safety of the HDP group trauma treatment intervention in reducing posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms in children. Results also show the Trauma Healing Training Program’s success in safely bringing an effective mental health treatment intervention provided by specially trained non-specialist mental health providers in a low-resource country.

Keywords: Healing Drawing Procedure, HDP; Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD); Non-Specialist Mental Health Providers; Low-And-Middle-Income Countries (LMIC); Adaptive Information Processing

Abbreviations: HDP: Healing Drawing Procedure; PTSD: Posttraumatic Stress Disorder; MHPs: Mental Health Providers; THTP: Trauma Healing Training Program; LMICs: Low-and-Middle-Income Countries; TG: Treatment Group; CG: Control Group; WHO: World Health Organization; ISTSS: International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies; PTs: Psychological Treatments; AIP: Adaptive Information Processing; EMDR-IGTP-OTS: Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing Integrative Group Treatment Protocol for Ongoing Traumatic Stress; CCT: Clinical Controlled Trial; EPT: Emotional Protection Team; ANOVA: Analyses of variance

Introduction

It is well established that Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs), (e.g., child maltreatment, abuse, neglect, witnessing domestic violence between parents) can lead to the development of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and can have a profound impact on an individual’s physical health [1-4]. Evidence also shows a dose-response relationship between ACE scores and adult physical health, as well as mental health problems. For example, Merrick et al. found that higher ACE scores increased the odds of experiencing drug and alcohol use, suicide attempts, and depressed affect in adulthood [5]. It is also known that PTSD is common and devastating disorder, that half of global cases of PTSD are considered persistent, and only a very small minority of those with severe PTSD symptoms in low-and-middle income countries (LMICs) receive specialty health care to treat the symptoms of PTSD [6]. While the long-term impacts of the effective treatment of ACEs during childhood are unknown at this time, a parallel issue to be considered is the lack of availability of mental health services in Kazakhstan, as well as globally, to provide such treatment during childhood, and even into adulthood. According to an official 2019 estimate by the United Nations, the population of Kazakhstan is 18,551,428 [7]. The Mental Health Atlas 2020, published by the World Health Organization (WHO), finds that there are an estimated 4,476 specialist mental health providers (MHPs), or mental health professionals, in Kazakhstan. Only 778 of those professionals specialize in the treatment of children and adolescents. That means that there are an estimated 24.13 specialist MHPs per 100,000 citizens resulting in only 12.10 specialist MHPs per 100,000 citizens that specialize in the care of children and adolescents [8]. The need for more available mental health services in Kazakhstan is great, to say the least.

As declared by the WHO, mental health is a basic human right [9]. Yet, like the situation in Kazakhstan, the worldwide shortage of specialist MHPs and the ever-growing gap between the availability of providers and the need for their services is widely understood. Most recently, the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies (ISTSS) published a briefing paper advocating for increased access to psychological treatments (PTs) in the global context and called for task-sharing and the training of non-specialist MHPs to be seen as a primary source to begin narrowing the gap between the need for mental health services and the availability of such services [10]. While there continues to be much work to be done, there is a small body of evidence that task-sharing PTs can be safely and effectively administered by non-specialist mental health providers [11-15]. This study hopes to contribute to that ever-growing body of evidence.

The Trauma Healing Training Program

This study was conducted as part of the development of the Trauma Healing Training Program (THTP), which is a specialized training being developed in the vein of task-sharing as part of the solution to the global mental health care crisis, particularly in LMICs. This training is being designed to equip non-specialist MHPs with safe and effective AIP-Informed trauma processing interventions to begin narrowing the great divide between mental health services needed and mental health services available in their communities. The THTP is a two-week training that includes learning two different group interventions as well as two individual interventions. Fieldwork is conducted on all four interventions with the in-person supervision and support of the THTP trainer. Specifically, for the HDP portion of the THTP, trainees receive a two-day in-person training on the HDP which includes demonstration of the HDP, lecture including defining trauma and recognizing its impact, learning self-soothing skills, provided understanding of the window of tolerance, as well working memory theory. Besides fieldwork, the training also includes practicum within the training team, so trainees can practice the administration of the HDP on each other before providing it to participants of this research project. In-person supervision and feedback from the trainer was provided throughout the training as well as during all fieldwork. Discussions of how to make the administration of the HDP culturally successful within the Kazakh culture and the specific context of the Caring Heart Public Fund were included. Six months of virtual follow up consultation from the trainer will be provided to the training team along with continued communication with the executive director of Caring Heart as the training team continues to utilize all the intervention tools of the THTP as they work to provide much needed mental health serices to the children of Caring Heart.

AIP Theoretical Model

In her 2018 text, Shapiro describes the Adaptive Information Processing (AIP) model and posits that memory networks of stored experiences are the basis of both mental health as well as pathology across the clinical spectrum [16]. When memories are adequately processed and adaptively stored, they form the foundation for learning and future perceptions, behaviors, and responses. When memories are inadequately processed and maladaptively stored due to high autonomic nervous system arousal states produced by adverse life experiences, pathogenic memory networks are formed, resulting in present-day suffering, difficulty, and symptoms (e.g., PTSD, anxiety, depression) [16]. Shapiro’s AIP theoretical model is the basis for the development of all treatment interventions incorporated in the THTP.

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a pervasive mental health disorder with devastating individual and societal effects, such as deterioration of basic functioning, hindrance of personal and professional relationships, and extreme psychological and physiological distress. PTSD leads to maladaptive responses that manifest in different forms, which include, but are not limited to hyperarousal, hypervigilance, flashbacks, nightmares, fear, horror, and impaired affective prosody and inability to adequately interpret emotional cues [17].

Healing Drawing Procedure Group Treatment Intervention

There are three levels to the THTP, and this study was conducted on Level 1, The Healing Drawings Procedure (HDP) Group Treatment Intervention. The HDP is modeled exclusively after the empirically based Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing Integrative Group Treatment Protocol for Ongoing Traumatic Stress (EMDR-IGTP-OTS) developed and extensively field-tested by Jarero et al. [18-22]. Like the EMDR-IGTP-OTS, the HDP is a scripted intervention incorporating elements of art therapy and utilizes the butterfly hug method as a selfadministered bilateral stimulation [19] to process traumatic material.

Previous Treatment Intervention Studies

The EMDR-IGTP-OTS, after which the HDP is modeled, was initially developed by members of the Mexican Association for Mental Health Support in Crisis (AMAMECRISIS) when they were overwhelmed by the extensive need for mental health services after Hurricane Pauline ravaged the coasts of Oaxaca and Guerrero in 1997 [18]. While this study is the initial research project to study the effectiveness of the HDP being provided by non-specialist MHPs, there have been numerous studies showing the efficacy of the EMDR-IGTP-OTS, including with children [23- 27], and provided by frontline workers, or non-specialist MHPs [11].

Objective

This clinical controlled trial had two objectives:

i) To evaluate the effectiveness, efficacy, and safety of the Healing Drawing Procedure (HDP) group trauma treatment intervention in reducing posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms among vulnerable children living in Taraz, Kazakhstan.

ii) To explore the effectiveness and safety of non-specialist mental health providers (MHPs), being trained in and delivering the HDP group treatment intervention as part of the task-sharing focused, Trauma Healing Training Program (THTP).

Method

Study design

To measure the effectiveness of the HDP on the dependent variable PTSD symptoms, this study used a two-arm clinical controlled trial (CCT) with a waitlist no-treatment control group design. PTSD symptoms were measured at three-time points for all participants in the study: Time 1. Pre-treatment assessment; Time 2. Post-treatment assessment; and Time 3. Follow-up assessment. For ethical reasons, all participants in the control group received intervention treatment after the follow-up assessment was completed.

Ethics and Research Quality

Due to the lack of an Institutional Review Board in the country of the study, the research protocol was reviewed and approved by the EMDR Mexico International Research Ethics Review Board (also known in the United States of America as an Institutional Review Board) in compliance with the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors recommendations, the Guidelines for Good Clinical Practice of the European Medicines Agency (version 1 December 2016), and the Helsinki Declaration as revised in 2013.

Participants

This study was conducted between September and November 2023 in the city of Taraz, Republic of Kazakhstan, in Central Asia. A total of 22 children (12 female, 10 male) ages 7-14 (M=10.09 years old) living in Taraz, Kazakhstan, met inclusion criteria and were able to complete participation in the study. Children were recruited for this study through their involvement with Caring Heart Public Fund, a legally registered non-profit organization in Taraz, Kazakhstan, focused on meeting the needs of vulnerable children and single mothers. All the children who participated in the study came there each weekday as part of the day program in conjunction with attending local schools. Participation was voluntary, and the participants verbally consented to the treatment while a parent or legal guardian signed a written consent in accordance with the Mental Capacity Act 2005. Inclusion criteria for the participants receiving the intervention were:

a) Being a child less than 18 years old.

b) Being a participant of the programs and services offered by Caring Heart.

c) Voluntarily participating in the study.

d) Not receiving specialized trauma therapy.

e) Not receiving drug therapy for PTSD

symptoms.Exclusion criteria were:

a) ongoing self-harm/suicidal or homicidal ideation,

b) diagnosis of schizophrenia, psychotic, or bipolar disorder,

c) diagnosis of a dissociative disorder,

d) organic mental disorder,

e) a current, active chemical dependency problem,

f) significant cognitive impairment (e.g., severe intellectual disability, dementia),

g) presence of uncontrolled symptoms due to a medical illness.

Instrument for Psychometric Evaluation

To measure PTSD symptom severity and treatment response, the optimal short-form of the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5) was used. This screening scale was not used to render clinical diagnoses. Rather, it was used to measure and track the severity of symptoms of PTSD in a context where the administration of the full PCL-5 was not feasible. The optimal short-form PCL-5 has been shown to detect virtually all cases meeting DSM-5 criteria of PTSD that would be detected by the full PCL-5, making it ideal for measuring and tracking symptoms of PTSD [28]. The instrument was translated and backtranslated to Russian, and the time interval for symptoms was the past week. The screening tool contains four items including:

i. Suddenly feeling or acting as if the stressful experience were happening again.

ii. Avoiding external reminders of stressful experiences.

iii. Feeling distant or cut off from other people.

iv. Irritable behavior, angry outbursts, or acting aggressively.

Respondents indicated how much they have been bothered by each PTSD symptom over the past week (rather than the past month), using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0=not at all, 1=a little bit, 2=moderately, 3=quite a bit, and 4=extremely. A total-symptoms score of 0 to 16 can be obtained by summing the items. The sum of the scores yields a continuous measure of PTSD symptom severity and can serve as a screen for detecting PTSD. Psychometrics for the optimal short-form PCL-5, validated against the full PCL-5, suggests that a score of 6 is the minimum to determine probable PTSD status based on DSM-5 diagnostic rules [28].

Procedure

Enrollment, Assessments, Data Collection, and Confidentiality of Data

Children were divided into a treatment group (TG) and a control group (CG) dictated by their school schedules. The children who went to school in the afternoon were available to participate in this study in the morning and vice versa. To provide the initial treatment to as many children as possible, the 15 children available in the morning (the morning group) were chosen as the treatment group as there were more children in the morning group. There were seven children available in the afternoon (the afternoon group), and so they were chosen as the control group. Which children went to school in the morning vs. the afternoon was dictated by the schedules of the school they attended. Age or educational level did not determine which school schedule each child had or their placement in the treatment or control groups. After the conclusion of all data collection for this study, for ethical reasons, the children in the control group were also provided with the same HDP intervention. For data collection Time 1, Trainees of the THTP were all trained in completing the optimal short-form PCL-5 with the children. The optimal short-form PCL- 5 was translated and back-translated into Russian as the entire training was conducted in English, with Russian translation. All trainees spoke Russian, and some trainees were also fluent in Kazakh. As each child was paired with a trainee to complete the assessments, care was taken to match Kazakh-speaking children with a Kazakh-speaking trainee and Russian-speaking children with Russian-speaking trainees. Trainees instructed the child to play a mental movie of all their difficult life experiences to identify the memory that bothered them the most. That memory was noted on the short form PCL-5 assessment paper and was used for all subsequent assessments as well as the HDP treatment intervention. Demographic information and consent forms, which also incorporated the exclusion criteria, were completed by a parent or legal guardian for each child as well.

]For data collection, Time 2. Post-treatment, the short-form PCL-5 was completed in person with each child one week after the completion of the HDP treatment intervention. The THTP trainees reminded each child of the memory that bothered them the most before answering the instrument to ensure participants were focusing on the same adverse experience each time, they completed the assessment tool. For data collection Time 3, three-week follow-up, the optimal short-form PCL-5 assessment was conducted three weeks after treatment was completed. The assessments were completed with each child in person by the same THTP trainee that had previously conducted the assessments with each child for data collection Times 1 and 2. All data was collected, stored, and handled in full compliance with the EMDR Mexico International Research Ethics Review Board requirements to ensure confidentiality. Each study participant gave their consent to collect their data, which was strictly required for study quality control. All procedures for handling, storing, destroying, and processing data were following the Data Protection Act 2018. All people involved in this research project were subject to professional confidentiality.

Withdrawal from the Study and Missing Data

All research participants had the right to withdraw from the study without justification at any time and with assurances of no prejudicial result. If participants decided to withdraw from the study, they were no longer followed up in the research protocol. There were no withdrawals during this study.

Treatment

Participants received six administrations of the Healing Drawings Procedure (HDP) treatment intervention as a group to reprocess pathogenic memories that were an average of 51.4 months old (4.28 years old). Two administrations of the intervention were provided each day for three consecutive days, totaling six hours of treatment. All administrations of the intervention were done in Russian with Kazakh translation. A different team member from the THTP training team volunteered to administer each set of the HDP while three other team members served as the Emotional Protection Team (EPT) per the 1:5 adultto- child ratio required for the HDP intervention. The remaining team members who were not either the leader or part of the EPT observed from the back of the room. Throughout the three days, all team members served either as the leader or as an EPT member; many served in both roles.

Clinicians and Treatment Fidelity

Nine of the non-specialist MHPs participated in the THTP and were members of the training teamwork for Caring Heart. Two trainees work for a similar organization in Shymkent, Kazakhstan. Consequently, the trainees all had different roles within their organizations, including teacher, program coordinator, administrative assistant, speech therapist, house mom, and social worker. While there are professional mental health services available in Taraz, they are quite limited in general and are not specialized in treating trauma to the best of the author’s knowledge. These non-specialist MHPs successfully administered the HDP intervention to the participants as part of the fieldwork portion of the THTP. The THTP trainer, a licensed mental health professional in the United States, also an EMDRIA Approved Consultant and EMDR Basic trainer, provided the two-day HDP portion of the training in person and supervised the fieldwork as part of the overall THTP. This team of non-specialist MHPs were chosen to participate in this training and research project primarily because of their demonstrated competence as leaders and teachers and because they already have working relationships and rapport developed with the children.

Treatment Safety

Treatment safety was defined as the absence of worsening adverse effects, events, or symptoms. No adverse reactions were reported or identified during subsequent post-treatment data collections or the remainder of the THTP.

Examples of the Pathogenic Memories Treated with the HDP

Examples of pathogenic memories treated during the HDP sessions were: Being physically abused and / or neglected, witnessing domestic violence between parents or other adults, being taken to a state-run orphanage, and subsequent fear of being returned there.

Clinicians’ Experience with the HDP Treatment Intervention

While trainees initially were concerned about asking the children to focus on their disturbing memories, they were quite pleased to see the results as the children processed through the traumatic experiences as witnessed through the reduction in the identified SUD (Subjective Unit of Disturbance) as is utilized in the HDP. Trainees were particularly impressed that they could provide relief to 15 children over the course of 6 hours rather than working with them individually on simple behavior modification.

Statistical Analyses

Analyses of variance (ANOVA) for repeated measurements comparing two groups, Treatment Group (TG) vs Control Group (TG) was applied to analyze the effects of the Healing Drawings Procedure (HDP) treatment intervention across the time at threetime measurements: Time 1. Pre-treatment assessment; Time 2. Post-treatment assessment; and Time 3. Follow-up assessment. Eta squared (η²) is reported to show the effect size. Comparison of means analyses was carried out using the t-test for both independent samples and within groups. Cohen´s d is included to report the effect size for t-test results.

PTSD

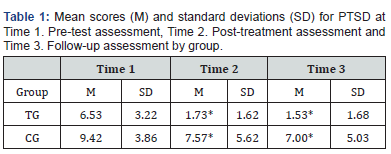

Results showed that the intervention had a significant effect for time on PTSD with a medium effect size (F (2,40) = 17.72 p <.000, η² = 470), a significant effect for group with a lower effect size was observed (F (1, 20 = 76.66, p<.001, η² = .404), no significant interaction was found.). Comparison of means between groups did not show significant differences for Time 1. Pre-test assessment (M = 6.53, SD = 3.22 vs M = 9.42, SD = 3.86). For Time 2. Post-treatment assessment, significant differences between the Treatment Group (TG) and Control Group (CG) were found, with a large effect size, t (20) = - 3.78, p=.001, d = -1.72, (M = 1.73, SD = 1.62 vs M = 7.57, SD = 5.62). For Time 3 Follow-up assessment, significant differences between the Treatment Group (TG) and Control Group (CG) group were also found, with a large effect, t (20) = - 3.85, p=.001, d = - 1.37, (M = 1.53 SD = 1.68 vs M = 7.00, SD = 5.03). Intragroup comparisons of means showed significant differences for the Treatment group (TG) between Time 1. Pretest assessment and Time 2. Post-treatment assessment with a large effect, t (14) = 5.42, p=.00, d = .955. See Table 1 and Figure 1.

*Statistically significant differences between groups

Discussion

This clinical controlled trial has two objectives: 1) to evaluate the effectiveness, efficacy, and safety of the Healing Drawings Procedure (HDP) group trauma treatment intervention in reducing posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms in a population of vulnerable children and 2) to explore the efficacy and safety of non-specialist MHPs being trained in and conducting the HDP intervention as part of the task-sharing focused Trauma Healing Training Program (THTP) being developed. A total of 22 child participants met the inclusion criteria and participated in the study. Participants’ ages ranged from 7 to 14 years old (M = 10.09 years). The data supports the effectiveness, efficacy, and safety of the HDP group trauma treatment intervention in reducing posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms in children. The results of the statistical analyses showed that the HDP group treatment intervention had a significant effect for time, with a medium effect size, and a significant effect for group with a lower effect size. A comparison of means between the treatment and control groups did not find significant differences for Time 1.

Pre-test assessment and for Time 2. Post-treatment assessment showing a similar baseline. Significant differences between groups were found for Time 2. Post-treatment and for Time 3. Follow-up with a large effect size in both assessments. Intragroup analyses of means showed significant differences for the Treatment Group (TG) compared Time 1. Pre-test assessment and Time 2. Post-treatment assessment with a large effect. Scores were maintained for Time 3. Follow-up assessment in this group confirming the effect of the treatment. In reference to objective number 2, exploring the effectiveness and safety of non-specialist mental health providers (MHPs), being trained in and delivering the HDP group treatment intervention as part of the task-sharing focused Trauma Healing Training Program (THTP), the study results also show the THTP success in safely bringing an effective mental health treatment intervention provided by specially trained non-specialist mental health providers in a low-resource country.

Conclusion, Limitations, and Future Directions

PTSD is a pervasive mental health disorder that has devastating effects on individuals and society. Therefore, there is a need for evidence-based, time-limited, cost-effective, and safe interventions to enhance the treatment of posttraumatic psychopathology. This study’s results showed that the HDP group treatment intervention can effectively, efficiently, and safely be provided in person to a child population with pathogenic memories to reduce PTSD symptoms. The participants reported no adverse effects or events during the treatment intervention administration or at the three-week follow-up. None of the participants showed clinically significant worsening/exacerbation of intrusion symptoms on the short-form PCL-5. Clinicians’ reports based on their experiences also suggest that the HDP is a provider friendly treatment intervention that can be successfully applied by novice and seasoned providers alike, yielding similar treatment results, facilitating clinician confidence. Limitations of this study are the lack of randomization, the different sizes of the groups with a small sample, and the three-week follow-up. Therefore, we recommend a randomized controlled trial with a child population with pathogenic memories (e.g., adverse childhood experiences) or on PTSD Criteria-A experiences, with larger samples, and with follow-up at three or six months to evaluate the long-term treatment effects.

To Know more about Psychology and Behavioral Science International Journal

To Know more about our Juniper Publishers