Journal of Surgery - Juniper Publishers

Abstract

Introduction: Meckel’s diverticulum (MD) is the most common developmental anomaly of the gastrointestinal tract [1]. MD is typically asymptomatic, however it can cause complications such as bleeding in children and small bowel obstruction in adults [2].

Cases: Two adult patients presented to Tullamore Hospital with features of small bowel obstruction (ileus). Both patients underwent CT scan, subsequent diagnostic laparoscopy and diverticulectomy of inflamed MD. The third case is a 12yr old boy who was presented to Khartoum Teaching Hospital with PR bleeding, then after two days developed abdominal distension and tenderness, with significant drop on hemoglobin. The patient underwent exploratory laparotomy which demonstrated MD with two perforated peptic ulcers at the ileum. Wedge resection was performed for the MD and primary repair of the ulcers after biopsy and edge refashioning. The post-operative period passed uneventfully for all three patients, with outpatient clinic follow up.

Discussion: The appropriate operation for symptomatic MD can be aided using a recommended HDR as cutoff 2.0 [3]. Basal ligation and frozen biopsy offer a novel and effective operative technique, as it can significantly shorten operative time [4]. For hemorrhagic ulcers and perforation, segmental and wedge resection for MD is recommended [5].

Conclusion:The laparoscopic approach was found to be effective as a diagnostic and therapeutic modality in patients with symptomatic MD. The foremost therapeutic objective is to achieve complete resection of MD along with ectopic mucosa. The HDR aids in determining whether diverticulectomy or wedge resection is the most appropriate MD resection technique

Keywords: Meckel’s diverticulum; CT-Abdomen & Pelvis; Height-Diameter Ratio; Heterotopic Gastric Mucosa; Per-rectum; Chest X-Ray

Abbreviations: MD: Meckel’s diverticulum; CT-AP: CT-Abdomen & Pelvis; HDR; Height-Diameter Ratio; HGM: Heterotopic Gastric Mucosa; PR: Per-rectum; CXR: Chest X-Ray.

Introduction

Meckel’s diverticulum is the most common developmental anomaly of the gastrointestinal tract with a prevalence of 2.0%. MD is reported to be up to four times more frequent in men [6]. This anomaly is understood to result from incomplete obliteration of the omphalomesenteric duct [1]. MD is a true diverticulum found at the antimesenteric border of the ileum, two feet proximal from ileocecal valve, two heterotopic mucosae found on MD, and two inch in length (The role of two) [5]. Usually MD is an asymptomatic, incidental finding however it can often cause complications such as small bowel obstruction due to inflamed Meckel’s or forming a loops of small bowel may become entangled around a fibrous cord. Meckel’s diverticulum can also lead to intussusception, volvulus, adhesions, stricture, and ileus or may become incarcerated within a hernia sac as in the litter hernia [2]. The aim of surgical management is to respect the diverticulum and all associated ectopic mucosa [7].

Case Presentation (1)

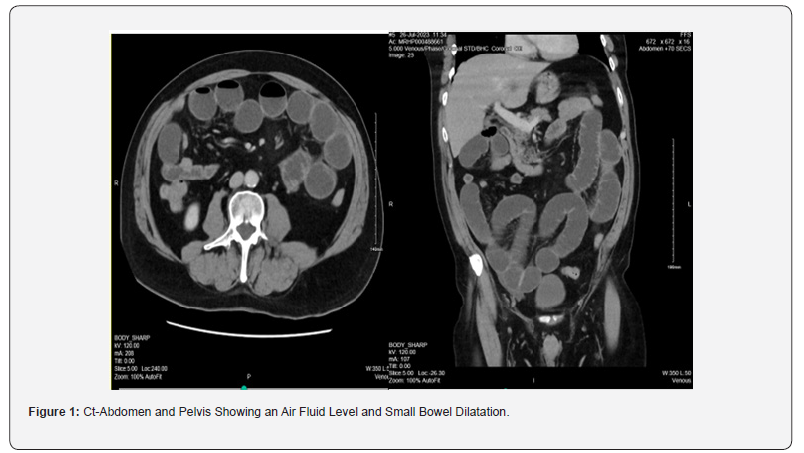

A 65-year-old male presenting to Tullamore Regional Hospital, complaining of abdominal pain, vomiting and absolute constipation for 3 days prior to admission. The patient’s abdomen was distended with generalised tenderness, however no surgical scars were observed. The patient’s admitted and laboratory results were as follows: Hb 13.0 units/dL, WCC 12.13 units/dL, CRP 15.5 units/dL, K+ 3.9 units/dL. A working diagnosis of small bowel obstruction was made, and the patient received I.V. fluids with nil per mouth. A CT-AP Figure 1 was ordered which confirmed a small bowel obstruction and the patient was consented for an emergency diagnostic laparoscopy.

Radiological Findings (Case 1) (Figure 1)

Procedure (Case 1)

Intra-operative laparoscopic exploration revealed an inflamed MD, and the entire small bowel was dilated sparing only last 60cm of distal ileum. Complete diverticulectomy was performed for inflamed MD with a linear stapler Figure 2. Subsequent histopathological analysis reported only an inflamed MD with no ectopic mucosa or neoplasia. The post-operative period passed uneventfully. The patient was discharged home in good condition on day four post-op. He was reviewed in the Outpatient’s Clinic six weeks later. The patient reported no post-operative complaints and the wounds well-healed.

Intra operative images (Case 1): (Figure 2).

Case Presentation (2)

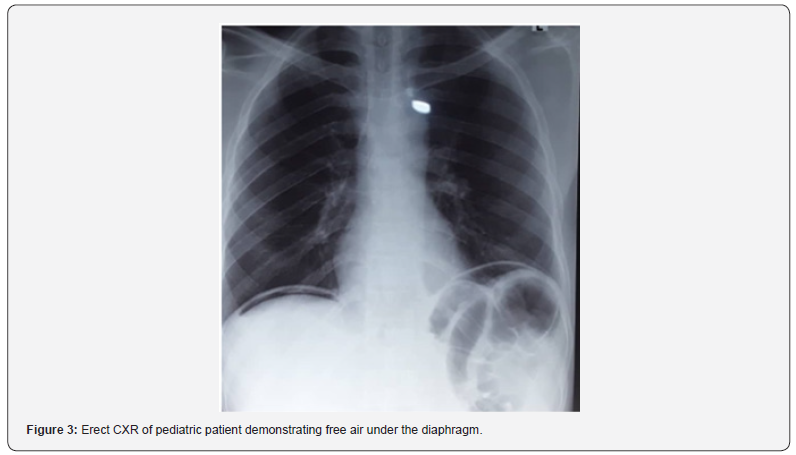

A 12-year-old boy was admitted to the Paediatric Surgical Unit in Khartoum Teaching Hospital with abdominal pain and bleeding per rectum. On examination the patient’s abdomen was soft, with right sided tenderness. Digital rectal exam was normal with no haemorrhoids or anal fissure noted. Two days postadmission the patient developed generalized abdominal pain, vomiting and there was abdominal distension and peritonitis. Routine haematological investigations revealed the patient’s serum haemoglobin had dropped from 14grams to 11grams. The patient therefore received a 50ml/kg transfusion of packed red blood cells, as well as IV antibiotics and I.V. fluids. An erect chest x-ray Figure 3 showed air under diaphragm. In discussion with the patient’s family, the consent was made for a laparotomy.

Radiological Imaging (Case 2): (Figure 3)

Procedure (Case 2): A right lower transverse laparotomy incision was made to explore the bowel. Surgical exploration revealed a short Meckle’s Diverticulum with a wide base at the distal ileum with two perforated peptic ulcers. The MD was removed via wedge resection. The perforated ulcer edges were then biopsied and refashioned before closure via primary repair. Postoperatively, intravenous antibiotics and PPI infusion were given, and postoperative period passed uneventfully, the patient tolerated oral intake. The patient was discharged on day seven post-op with follow up in the outpatient clinic in three months. Histology afterwards confirmed a completely resected MD with ectopic gastric mucosa.

Case Presentation (3)

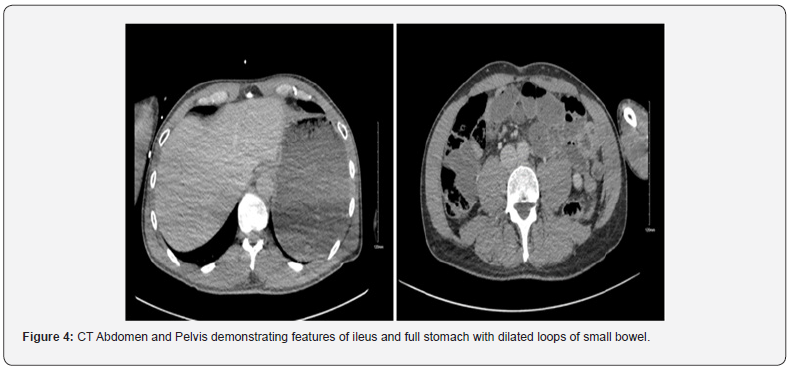

A 60-year-old male presented to the emergency department of Tullamore Regional Hospital with signs and symptoms of small bowel obstruction beginning 2 days prior to admission. Examination revealed a distended abdomen with generalised tenderness. Routine investigations: WCC 8.23 units/dL, CRP 31.9 units/dL, K+ 4.2 units/dL. The patient was admitted for nasogastric tube suction, I.V. fluids and analgesia. A CT-AP showed partial small bowel ileus with dilated loops of small bowel Figure 4. The patient was consented for an emergency diagnostic laparoscopy.

Radiological Imaging (Case 3): (Figure 4)

Procedure (Case 3)

Laparoscopic exploration detected an inflamed MD at the distal ileum with cord adhesion to the umbilicus Figure 5. Dilated small bowel was observed proximal to the adhesions. The inflamed MD was resected at the base with a linear stapler (diverticulectomy). The histopathology report showed an inflamed MD with ectopic gastric mucosa. The post-operative period passed unremarkably. The patient was discharged day three post-op and reviewed at OPD at 4 weeks with well healed wounds and no post-operative complaints.

Intra operative images (Case 3)

(Figure 5)

Discussion

Symptomatic Meckel’s diverticulum typically occurs in the first two decades of life and almost exclusively before the fifth decade [6]. The adult cases outlined above both contradict this pattern given both patients were above 60 years of age. In adults, MD is usually an asymptomatic condition with only about 4% of those affected developing complications [8]. The reported mechanism of intestinal obstruction in MD includes intussusception, adhesion, and volvulus. Furthermore, inflammation of the MD can cause small bowel ileus as seen in our two adult cases [1]. While obstruction is the most common complication in adult patients, gastrointestinal bleeding is the most common presenting symptom of MD in children [2]. This aligns well with the presenting complaints of the three cases in this report. Moreover, another study reported haemorrhage as the most common presentation in children and is reported in over 50% of their symptomatic cases [7]. Other complications of MD include perforation, umbilical fistula, cyst, fibrous cord with umbilicus, while double Meckel’s and carcinoid tumour are also reported in the literature [8]. 90% of bleeding diverticula contain heterotrophic mucosa, most often gastric mucosa (71%), contains acid-secreting parietal cells which can lead to ulceration and haemorrhage as observed in our paediatric case. Histopathological analysis demonstrates ectopic pancreatic tissue in 12.0% of resected MD [6].

The diagnosis of MD may be challenging as the condition often remains asymptomatic or may mimic various diseases which obscures the clinical picture. For example, MD often mimics the presentation of acute appendicitis in children, as 11% of complicated MD were initially misdiagnosed as acute appendicitis [8]. The probability of onset of complications decreases with age, therefore the diagnosis of MD in adults is often incidental [9]. Exploratory laparoscopy is an important diagnostic tool, especially when perforation has occurred [9]. In the case of hemorrhage, as often seen in pediatric MD, mesenteric angiography and embolization are reported as diagnostic and therapeutic tools [5, 10]. The advent of technetium (Tc) 99m radionuclide scanning has greatly facilitated the diagnosis of MD especially when the anomaly contains heterotopic mucosa [5]. Since Meckel’s diverticulum (MD) is rarely diagnosed in adults, there is no consensus on the optimum operative technique for asymptomatic MD. Indeed, there is disagreement as to whether an incidentally discovered MD should indeed be respected at all [11]. However, research suggests up to 57% of resected MD were found incidentally which contradicts the view that routine resection is not indicated in incidentally discovered cases [3].

Resection of incidental MD is explicitly not recommended in patients with peritonitis, major abdominal trauma, ascites, or in the context of older age, malignancy, or immunosuppression. However, research does suggest resection of incidental MD may be appropriate in the context of risk factors which may predict future complications. Risk factors for MD complications include male gender, age younger than 40 years, diverticulum longer than two centimeters, narrow neck of the diverticulum and the presence of macroscopically mucosal abnormalities noted at surgery [11]. On the other hand, some researchers disagree with the view that the external appearance of the MD can reliably predict the presence of HGM, and therefore argue macroscopic appearance cannot reliably aid resection decisions in the context of an incidentally discovered MD [3]. Nevertheless, the definitive treatment of symptomatic MD is laparoscopic or open diverticulectomy via wedge or segmental resection. The type of procedure depends on; (a) the integrity of diverticulum base; (b) the presence and location of ectopic tissue within MD [8]. Location of ectopic mucosa can be predicted based on height-to-diameter ratio. Long diverticula (height-todiameter ratio >2) have ectopic tissue located at the body and tip, whereas short diverticula have wide distribution of ectopic tissue surrounding the diverticulum base. A greater HDR has also been found to be an independent risk factor for perforation [11].

When indication of surgery is simple diverticulitis, diverticulectomy should be performed for long and wedge resection for short MD [11]. Simple transverse resection is not recommended for short MD, as resection followed by anastomosis seems preferable to wedge resection or tangential mechanical stapling, in order reduce the risk of leaving behind abnormal heterotopic mucosa [4]. New operative methods for MD include basal ligation combined with intraoperative frozen section. Using intraoperative histological feedback on the existence of residual ectopic mucosa, surgery is either terminated or further wedge intestinal resection or bowel resection was performed as required. Basal ligation is a safe and effective operation method as it can significantly shorten operation times and postoperative fasting time. For hemorrhagic ulcer and perforation, segmental and wedge resection are indicated as performed in our pediatric case [5,12-15].

Conclusion

The laparoscopic approach was found to be effective as a diagnostic and therapeutic modality in patients with symptomatic MD. Once MD has been diagnosed, the fundamental therapeutic aim is to achieve complete resection of the diverticulum along with ectopic epithelium. The HDR can assist in determining the most appropriate resection technique. Longer MD should be resected with diverticulectomy whereas wedge resection is the optimum technique for short MD.

To Know more about Open Access Journal of Surgery

Click here: https://juniperpublishers.com/oajs/index.php

To Know more about our Juniper Publishers

Click here: https://juniperpublishers.com/index.php

No comments:

Post a Comment