Juniper Online Journal of Public Health - Juniper Publishers

Abstract

Background: The Balanced Score Card (BSC) is a possible method to tackle the challenges related to the strategic planning of public hospitals in Hungary.

Aim: To assess the implementation of the Hungarian version of the BSC method in the hospital sector.

Methods: The adapted BSC method was implemented in 22 publicly financed Hungarian hospitals and assessed through questionnaires, in-depth interviews, and hospital and territorial level workshops.

Results: The inner communication channels have been partly distorted, and a bottom-up planning is crucial in the planning process. Wide range of involvement of hospital staff proved successful during the strategic planning and can guarantee a systematic approach to the implementation of strategic plans.

Conclusions: The scaling up of the BSC method should be enforced by the necessary regulatory amendments.

Keywords: Strategic planning; Balanced scored card; Qualitative analysis; Hospital sector

Introduction

Strategic thinking and planning have gained increasing importance in the public sector of both developed and developing countries. Hospitals require vigilant leadership and strategic vision from managers who consider different alternatives to tackle the uncertainty service providers are faced with. Uncertainty in the health care sector is reduced through the clarification of the goals of hospitals whilst taking environmental aspects into consideration. Strong hospital management leads to better-quality health service provision, and strategic planning is crucial to sustainable growth and success within the field. The strategic planning of health care institutions is similar to industrial, commercial and service organizations, especially in terms of their assets. Strategic theories and analytical methods applied by companies and business organizations can also be applied by the publicly funded hospital sector.

The biggest differences can be found in their content: the goals, the certain environmental factors, the expectations of stakeholders, the definition of strategic dimensions, the nature of the strategic objectives and the specific range of tools [1]. A strategic objective must be measurable, precise and distinct in time since it has a great impact on hospitals [2]. It is not a solution but rather a tool within this competitive market that helps to tackle the challenges of the health care sector through enabling hospitals to operate in a more flexible way and adapting more easily to the possible changes in the environment [3].

The so-called Balanced Scorecard (BSC) can further improve strategic management and lead to better evaluation and implementation [4]. The Balanced Scorecard was first suggested by Robert Kaplan & David Norton [5] in their 1992 article [5]. Lee [6] stated that the Balanced Scorecard works efficiently as a legitimised framework for performance improvement because it is simple to understand and use, it has a clear purpose, is derived from strategy and prompts continuous improvement [6].

Balanced Score Card – as a key method of strategic planning and implementation

The Balanced Score Card (BSC) had been developed by Kaplan and Norton in the mid ‘90s [5]. The basic methodology has become very popular since then and formed part of several strategy implementations. This tool has been recognised mainly due to its ability to measure and monitor results in a novel perspective. Today, it is considered to be the most universally applied performance measurement system among the new generation of strategic management tools. Generally, this method is aimed to build indicators and objectives from 4 aspects: financial, clients/users, internal processes and finally learning and resource development. Also, the BSC method offers a structured combination of financial and non-financial indicators that generate a new managerial tool for higher and expectedly more efficient strategy of the health care organization.

Contradicting visions should also be taken into account when choosing the right indicator for the analysis and elicit whether clinicians and managers share their views on the most relevant parameters [4]. Thus, the main purpose of BSC is the support of strategy implementation, however, using the Balanced Scorecard in healthcare delivery comes with many challenges due to its complexity. This field is characterised by a very diverse and wide range of stakeholders including medical officers, regulatory bodies, the state and other key actors. Moreover, it is an area where costs are rapidly growing, hence, it is crucial to find the right balance between resource allocation, long term benefits that are generated through the investment in health, disease prevention, health promotion and urgent health needs in the short term [7].

Related methodologies, including the strategic map and a conceptual framework and representation mode also proved to be very useful as a part of a strategic plan. The strategic map – a visual representation of the strategy – as a graph composes the BSC dimensions, and in each dimension the main strategic objectives, the links between them and other information about target population and vision. It is important to note that every strategic map is different and follows a unique design, and they can consequently adjust to each strategic situation.

The strategic management of hospitals and international health systems are affected by the following tendencies: increasing number of chronic illnesses, rise of previously unknown diseases, aging population, rapid development of health technologies, expansion of health tourism, lack of human resources in health care, increase in consumer needs and awareness, and finally, the influence of the all-time political state. These factors induce advancement in the level of both health policy and the individual institutions, considering environmental circumstances [8].

The regulatory and health policy framework of the Hungarian hospital sector

In Hungary, the vast majority of the hospital sector – the formerly municipal property local, county, regional and capital hospitals – was centralized to the State according to the Decision of the Parliament in two waves: January and May 2012. Only churches and smaller hospitals owned by civil organizations remained independent from state ownership and direct supervision. As a result, the hospital sector became a part of the central administration, all of these hospital had to adapt the legal form of public institutions following the rules of general government legislation, lead their bank account at the State Treasury, and employ their employees as public servants. From a strategic planning point of view, these laws and government decrees create a highly rigid regulatory framework since 2012.

The main income of the publicly financed hospitals comes through prospective payment system (PPS), the Hungarian version of DRGs which was introduced in 1993, while chronic care, nursing wards and rehabilitation are paid by weighted daily fees. Also, hospitals provide the vast majority (approximately 75%) of out-patient care, specialist consultation and diagnostics (e.g. CT, MRI) paid by activity through the so-called German scores, and more than half of the publicly paid one-day surgery cases. As a whole, this sector represents the 62% of the inkind benefit. The individual resources of hospitals from private sources is rather limited: 3-5% of the hospitals on average, only a small proportion of them can implement more VIP rooms, extra diagnostic or procedure capacities.

The size of the hospital sector administers approximately 1.8% of the Hungarian GDP and about 1/3 of the public expenditure of the health care sector [1]. Hence, the importance and economic power of hospitals in rural cities is rather only a proposal.

Strategic planning pilot program for hospitals in 2014-2015

The aims of the Hungarian pilot program called TÁMOP- 6.2.5-B-13/1-2014-0001 “Maintaining Organizational Efficiency in the Health Care System - Establishing Territorial Cooperation” included the development of the health service function methodology and the development of the function through methodological support at national, regional and community level which supports the effective implementation of care and pathway organizational processes. The main objective of this project was to develop a standardized methodology primarily for the 105 state owned hospitals. Moreover, it was also important to create a well-established, transparent planning framework for providing institutions based on needs and performance, as well as establishing a consistent sectorial system and maintaining strategic planning.

A prominent goal of the program was to strengthen the National Healthcare Services Centre of Hungary (ÁEEK) in the role of an institution which maintains the systematic development of strategic institutional governance with the help of the BSC method. The development of strategic management aims to support the path which improves the awareness, consistency and cost-effectiveness of the sector so that county providers can stand public scrutiny. This strengthens the cooperation between different stakeholders of the institutional system. The above-mentioned functions were not operating according to the standards of the National Healthcare Services Centre of Hungary (ÁEEK), hence, the purpose of the enhancement of strategic management consisted of the following:

a. Developing a results-oriented institutional performance management system;

b. Adjusting the coordination of the sectoral professional and infrastructure planning to national, regional and institutional goals, including a methodological basis;

c. Creating a link between strategic planning and reporting and becoming part of the benchmarking system for institutional management and regional directorates;

d. Developing strategic planning processes embedded in the management system at sectorial level;

e. Clarifying managerial competences and tasks, strengthening the management approach, unifying HR functions and procedures in institutions with state provision.

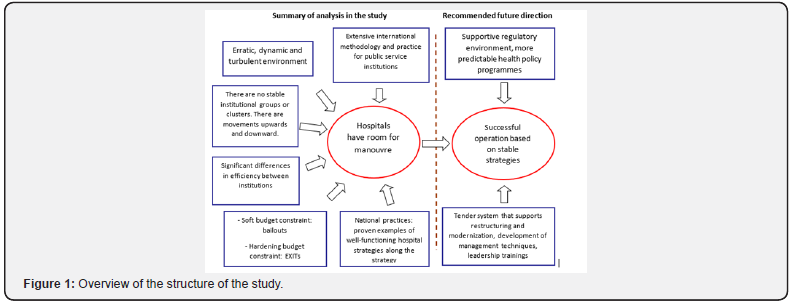

A formalized study about the use and effect of BCS strategic management method in the hospital sector has not been conducted prior to this project. A hypothesis of this study is that the BSC has an advantage compared to the former professional organizational development plan because it incorporates a wide range of financial and non-financial issues and offers a measurable set of indicators. This project assumes an ideal situation as proposed within the key findings of a doctoral thesis (Dózsa 2011b) which was based on an EU funded project that opened new perspectives whilst building on previous experience, and moving towards a higher level of general environmental analysis, ensuring more stable operational environment and a profound, specified strategic planning methods for hospitals (Figure 1)

Source [1] During the implementation phase of the project, a professional consultancy Kockázat Kutató Intézet [8] was involved, led by one of the key strategic planning experts of Hungary [8]. The members of this company with the collaboration of the project team had the responsibility to develop the adapted BSC method for Hungarian hospitals and to plan and implement a 1,5 years long strategic planning methodological development process involving 22 pilot public hospitals. Careful consideration was given to the selection of the two targeted regions from the possible six convergent regions, and finally, two regions were selected to this Strategic Planning pilot program which were not University Clinics.

The execution of the program generated certain organizational and human resources demands, including the development of strategic management skills within the organization of the National Healthcare Services of Hungary (ÁEEK), especially for the creation of a knowledge centre for the Balanced Scorecard methodology, as well as developing, documenting and communicating the management practices of strategic management and identifying the leaders. In each participating hospital, strategic management/BSC officials were appointed, who oversaw all BSC related operations.

Aims and objectives

The aim of this study was to assess the implementation of use of adapted version of Balanced Scorecard strategic management methodology in the hospital sector and to compare it with some international examples. This aim is achieved through the following objectives:

a. To develop an adapted version of the BSC method (schemes, tables, planning templates);

b. To share knowledge among the hospital staff about the BSC-based strategic planning method;

c. To test workshops as a general tool for planning hospital and territorial strategies;

d. To compare the international practice of applying BSC in the hospital sector of other countries with this recent Hungarian experience.

Methods

General methods

The methods composed of a systematic literature review on the application of BSC in hospitals, quantitative data analysis based on a questionnaires about the attitude of the staff of selected hospitals, in depth interviews with director generals about strategic thinking, and strategic development training and workshops with top-, intermediate managers and invited experts of hospitals facilitated by strategic planning experts.

Overall, 212 persons from 22 publicly financed Hungarian hospitals were involved in the program to adapt BSC in the chosen Hungarian hospitals in two regions. The concept of methodological development was reviewed along with the individual performance management system, the implementation proposals, and individual leadership objectives were also tested for all 22 institutions. The same factors were examined based on the questions of the interviews in each provider institutions. Inquiries performed included SWOT analysis, situation analysis and examination of strategic aims for the future.

Data sources

General data about the hospital sector as a whole and about the analysed hospitals were obtained from public data sources of the National Health Insurance Fund Administration (former OEP, currently NEAK) and the Central Statistical Office (KSH). Strategic planning documents were made available through the documentation of the EU funded pilot program.

Statistical methods

The starting point of this project was the adaptation of the Balanced Scorecard method which was tested in two regions of Hungary. This pilot programme can be considered as a methodological challenge since the researches had to develop the methodological framework itself as a first step. The strength of this project is that it has a heterogeneous sample. Interviews were used to collect information regarding the adaptation of the Balanced Scorecard. Interviews were conducted with the directors of 22 public hospitals in two regions (Northern Hungary and Western Transdanubia) of the country and the process of strategic planning was followed through in these locations.

It is of particular importance to this analysis that the included hospitals are publicly financed because they rely on external stakeholders. Interviews were supplemented with the systematic analysis of strategic outlines of these institutions. In each institution, all the executives involved in the program filled out a questionnaire with the same content. The questions covered the entire workflow of the project, from preparation to completion. In addition to the keeping deadlines, commented were gathered on the methodology itself, the involvement and role of external experts, so that feedback could be provided on the entire spectrum of the project. The questionnaire consisted of 19 questions, and in most cases, a four-item scale was used. Depending on the questions, respondents were provided with different textual interpretations. Besides gathering feedback, the main aim of the questionnaire was to interpret the lessons learned from the implementation of this pilot project.

Limitations

The approach used in this research is a participative method which has some limitations. First, only basic descriptive statistics rather than complex quantitative methods can be used during the evaluation of the results. Second, challenges to the practical integration of the programme is also a deficiency because the program was only tested in 22 public hospitals, and the possibility of scaling it up to a national level in Hungary is based on several assumptions, but it would certainly generate demand for additional human resources. Further research on the evaluation of this pilot programme could provide a better understanding regarding the use and experience of the Balanced Scorecard in the hospital sector. Up to this point, only the strategic process and the applied methods could be analysed, and there is no outcome or performance data to measure the effect of the elaborated strategic planning documents.

Results

Findings of the management interviews and staff questionnaire

Interviews with hospital directors found that each hospital completed their strategic plans differently. Adequate financial and human resources were available to develop plans in the larger institutions, but this caused a problem for smaller ones in rural areas. Neither their financial resources were involved with experts, nor were internal human resources available. The scope of the planning also varied between institutions. In some cases, the entire hospital management was involved in the planning process, but there was also a case where only the Main Director and the Financial Executive were included. Overall, these strategic plans could be considered as professionally prepared investment documents with high data content which can be used in the strategic planning process, but they cannot be treated as a strategic plan due to some deficiencies such as the absence of Stakeholder analysis.

Beside these issues, most of the examined institutions are in a situation in which they are faced with limited space in strategic decisions due to insufficient opportunities in generating funding and scarce financial resources. The hospitals could carry out the analytical tasks on a satisfactory level, especially in those institutions which are bigger and have sufficient human resources. This needs to be considered when scaling up the process strategy to less resource-intensive institutions, and when planning the provision of adequate support from the region or the central organization that is responsible for the provision of the institutions. Due to adequate groundwork, the institutions can carry out the analyses without further action, and in case of deficiencies, the appropriate methodologies can be applied correctly.

The recognition and acceptance of the Balanced Scorecard was clearly positive among the participants and fitted to the management’s view considerably well (>95%). Most respondents stated that they assume 5-6 months, or more would be the optimal duration for creating an appropriate strategy. The hospital leaders considered the building phase and the creation of the Balanced Scorecard structure more difficult than the status analysis phase and required more help in those activities. In both cases, the proportion of those requiring continuous help from a professional was significantly high (>40%). There was only a small number of directors who did not expect any support.

There were several issues that caused difficulties for most of the institutions involved, including the determination of a clear aim which is key in the process of strategic planning, having clear visions about the future operation, as well as the creation of the strategic map. Moreover, 70% of participants needed help with classification in the various dimensions. There were also problems with the correct labelling of categories and with some differences from the moderators’ point of view. Only 10% of hospitals could create a professionally decent strategic map due to the lack of time.

Key characteristics of the environmental analyses

Main findings of the SWOT analyses

The purpose of the SWOT analysis is to summarize the external and internal factors influencing an organization. It is a summarizing evaluation which includes prior conclusions and is also suitable for interpreting results on a valuebased manner through the dimensions of SWOT. Due to this analysis, the management can have a comprehensive view about the organizational strengths and weaknesses, as well as opportunities and threats of the present that affect the future success of the institution with varying weight and cannot be separated from the institution. Based on the review of the analysis, it can be stated that the length of the analyses was the appropriate period in two-thirds of the cases. Perhaps the SWOT analysis meant the least challenging task for each hospital.

Characteristics of the stakeholder analyses

Pilot experiences related to stakeholder analysis proved that the institutions were mostly able to identify their stakeholders using the strategic planning method. However, they had difficulties when determining their partners and competitors. In addition, evaluation of stakeholders caused some dilemmas because they misunderstood the concepts of being critical and having the option to suggest things. The definition of key stakeholders and actions only happened in case of one institution. In most of the prepared strategies, the analyses were delivered by the organization, but no conclusions have been drawn.

The depth and quality of the hospitals’ analyses on selfevaluation showed quite wide variations. Only 60% of the institutions went through the analysis to show the extreme values per dimension, while the extreme values show the points in question by analysing the answers to each question by scales of values, which can be used to identify the areas to be strengthened. Textual evaluation of the results was not thoroughly carried out either in most of the hospitals.

Overview and systematic comparison of the 22-hospital strategic plan

There were three different kinds of hospitals involved in the pilot programme; specialized hospitals, city hospitals and county hospitals. Overall, it can be concluded that there is no correlation between the strategies of hospitals that are similar in size. Each hospital reported an average of 15 strategic goals and elaborated an average of 27 indicators in four separate dimensions. One general pattern that could be observed across the strategies is that there are similar goals drafted out in those dimensions that are related to finance or management, however, those related to professional growth are more specific and diverse across the various institutions.

BSC dimensions and strategic objectives

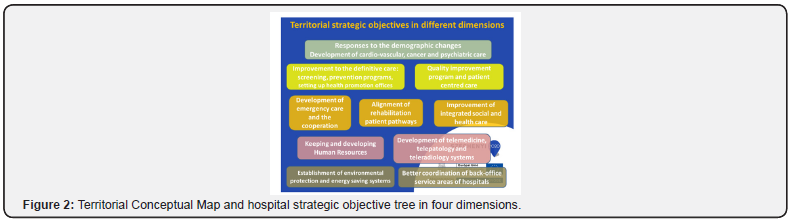

The strategic goals generated during the study were categorized into four different dimensions:

a. Service recipient and service standards,

b. Service provision and operation processes,

c. Competence and organization development,

d. Finance/Management (Figure 2).

The analysis suggests that there were 8-9 indicators connected to Service recipient and service standards, 8 to Supply and operation processes, 5-6 to Competence and organization development and finally 4-5 indicators to Management on average chosen by the hospitals. There are some common strategic goals that are mentioned by all three types of hospitals. Principally, each hospital includes the introduction or further advancement of one-day care or outpatient care in their list of strategic goals within the dimension of Service provision and operating processes. Most of them emphasizes the importance of ambulatory surgical care. This improvement is mainly associated with more efficient time management which was another typical goal to be achieved. One of the city hospitals state that: “In case the intervention can be performed in the form of one-day surgery/cure-type care, we aim to perform them accordingly in an even higher proportion.” Hence, providers note the importance of reduced nursing time, – in case it is medically justified – and significantly shorter patient record time.

Another common ground that most provider institutions agree on is growth related to IT systems which basically appears within the goals all four dimensions but in different forms and with different wording. As one of the specialized hospitals states: “It is necessary to simplify and develop IT tools to help patients and their relatives, as well as internal information management.” This statement is encouraged by city hospitals as well: “Providing IT tools and software that meet the technical standards of the age.” To sum up, according to the providers, exploiting sectorial IT development, complex management of health data and the creation of controlled transparency ensure efficiency gains.

The ability to keep professionals that are already employed by the institutions is mentioned by nearly all hospitals: “ensure a sufficient number of qualified human resources matching the needs of the hospital” and “keeping residents within the institution on the long run”. This emphasises the importance of developing existential security for workers.

Some of the common strategic aims related to Finance/ Management included: revenue increase, liquidity balance, economic balance and cost rationalization. While there were some typical aims regarding Service provision and operation processes as well, (extension of e-health activities, IT development, development of medical and nursing care) this dimension proves to be more diverse with goals such as: aiming for protocol-based care and improvement of internal and external communication.

Strategic indicators for measuring the strategic implementation

Indicators were subsequently categorized into the abovementioned dimensions. Providers participating in the pilot programme seem to be the most concerned about patient satisfaction. Without one exception, all hospitals mention it as one of their indicators within the dimension of Service recipient and service standards: “The basic tasks of our hospital include the improvement of the conditions of patients and increasing their satisfaction. Patient satisfaction is a complex matter defined by the length of the waiting list, the conditions of patient reception, the quality of the accommodation, the empathy of the staff, the correctness and clarity of the information provided, and the technical equipment used for treatment.” – as it is stated by one of the city hospitals.

Another factor that affects all three types of hospitals is the initiative to decrease the number of permanently vacant positions which is planned to be achieved by increasing the proportion of specialized medical practitioners and resident professionals. Media appearance and the operation of control and management information system also appear among each type of indicators of the institutions. On the other hand, there is an indicator in the dimension of Competence and organization development which is exclusively mentioned by city hospitals. This indicator is to avoid fluctuation of professionals and to increase their loyalty to the institutions. However, some of the indicators are only relevant in certain types of institutions, for example increased attendance of conferences and the improvement of healthconscious nutrition – “to achieve the appropriate amount of salt intake prescribed by law and to further reduce it” – was only indicated by specialized hospitals.

Typical strategic actions of Hungarian public hospitals

Similarly, to the strategic goals and indicators, the same dimensions are used for the examination of strategic actions. In case of actions, 9.3 indicators turned out to be connected to Service recipient and service standards, 8.9 to Service provision and operation processes, 6 to Competence and organization development and 4.3 indicators to Finance/Management on average. There is no significant difference between the numbers of strategic actions and between the types of hospitals either. Specialized hospitals collected 35, city hospitals collected 27.4 and county hospitals collected 28.7 strategic actions on average. A strategic action that is emphasized by all hospitals regardless of which type they belong to is to act as a professional practice institution for medical students, including nursing students. As one of the county hospitals states: “Well-organized, systematic graduate and postgraduate training, retraining and research and development - in cooperation with universities and hospitals of the region. Developing the personal and material conditions of a practical teaching background.” Relating to this strategic action, recruitment of entry level professionals is also a popular indicator among the participating hospitals.

Another common strategic action is infrastructural restoration or expansion and rearrangement of already existing departments. In addition, patient comfort, patient satisfaction and the extension of screening tests are also in the centre of planned advancements: “Increase the number of screening days, operate and develop self-sustained imaging diagnostics, promotion of screening tests.”

Discussion

The aim of this paper was to describe the experiences gathered during a Hungarian pilot study of introducing the Balanced Scorecard method to the hospital sector. As a commonly used tool, the BSC needs to be adapted to the institution in question considering its unique specialties. An advantage of this tool is that it is adequately flexible which allows it to fit for a variety of different situations [4]. Moreover, in this particular case, the public sector requires public managers to adopt comprehensive performance measurement tools to assist them in choosing from a diverse set of measures in public sector organisations. Another challenge the organisations need to deal with is that they must be able to provide a complete measure of performance that is comprehensive, readily coherent and is applicable to public actors [5,10].

One of the most common and internationally used tools in strategic management is SWOT analysis. For example, in the Netherlands more than 80% of health managers from hospitals, home care organizations and nursing homes reported the use of SWOT analysis in their strategic management processes (van Wijngaarden – Scholten GRM – van Wijk, 2012).

A research conducted in Serbia [11], which focused on healthcare institutions in urban areas and used a survey to assess the current state of strategic management in Serbia, aimed to propose a model to facilitate and improve this mechanism. Moreover, it also aimed to analyse the existing systems in some other countries such as the USA, Afghanistan, Sweden, Canada, Denmark and Germany. The research method was based on a survey, including 20 questions which were selected after conducting interviews with focus groups and performing an analysis of present trends in implementation of strategic management in healthcare institutions worldwide. A total of 43 institutions were surveyed within the course of the study. Researchers evaluated the following strategic management techniques (for the analysis of both internal and external environment), in order of frequency of use: SWOT analysis was used at the rate of 50%; PEST analysis at 23,5%; objectives tree at 14,7%, gap analysis at 17,6%; and finally, stakeholder analysis at 20,6%. It is also worth mentioning that the most frequently used forecasting methods were the scenario method (23.5%) and the simulation method (23.5%) (Mihic – Obradović – Todorovic – Petrović 2012: 3448-3452).

Further researchers [11] in a neighbouring country also studied the possible implementation of strategic management tools for hospitals in order to achieve better performance and operational efficiency. Milic and his colleagues assessed the current practice of strategic management in healthcare organizations in Serbia using surveys that were analysed by statistical methods. They revealed that in many of the HC organizations a strategic plan has been developed (strategic goals were clearly defined), but they failed to successfully and systematically implement it. They also highlighted the importance of standardized methodology, such as the Balanced Scorecard which was rarely used among the HC institutions.

Evaluation of the hospital strategic environment

Following the remarkable centralization, the regulatory framework has become rather rigid (constricted) from the perspective of strategic planning, with a rather narrow space for unrestricted managerial decisions. The managers are faced with rigid regulation of HR management, performance management, options to change, significant modification of capacities of hospitals (e.g. N. of ICU beds, STC beds, N of operational rooms), increase in the contracted volumes of paid services.

However, as it was confirmed in a former analysis, the generic and specific environments of hospitals still remained turbulent (many factors are in dynamic changes) [12]. Furthermore, enough space remained for strategic options, including alternatives in the following three dimensions: selection of professions, new service lines, educating or attracting new specialists, purchasing and implementing new equipment (e.g. diagnostics and endoscopic machines), and to increase the private sources of the institution. Finally, convincing supervisors and representatives of state owners to integrate and to lunch fusion with smaller health centres, to expand to a wider area if coverage (more habitants) in order to increase potential demand for hospital services. Regardless of the above described strategic options, it could be concluded that a strategically thinking hospital manager, who can behave as a real leader, has sufficient strategic choices despite the rigid regulatory framework.

International comparison of strategic planning process and hospital plans

However, the Ministry of Health in Chile (Minsal) has developed comprehensive recommendations for hospitals and other healthcare institutions to establish and implement them in their strategic documentation. Evidently, they do not include the Balanced Scorecard, but their approach is considered to be nearly identical. The Chilean strategic plans are also based on the breakdown of objectives, indicators and actions. Typical strategic objectives include customer satisfaction improvement, rationalizing the physical infrastructure of hospitals and better management of human resources [13].

The general management of Central Regional University Hospital in Lille, France introduced the Balanced Scorecard methodology in 2005. The methodology was used to test and evaluate actions that were designed to meet the needs of patients, staff and institutional partners. Within the BSC approach, the concept of classical performance was balanced by adding 3 additional perspectives to the financial one: patients, missions, internal processes, and change management. Performance was measured by indicators assigned to viewpoints. A separate organization was established for the implementation of the projects. To achieve their strategy, a separate Balanced Scorecard office was established which focus on 14 strategic actions, for instance, development of outpatient care, patient flow, rehabilitation care and sustainable growth [13].

A further example is a first-class emergency hospital located in Munich, Germany, named Kreisklinik Ebersberg. Their Balanced Scorecard identifies four perspectives: customer and market perspectives, prospects for employment and learning, clinical management and financial perspectives, and prospects of improvement and processes. The distribution of perspectives follows the standard Balanced Scorecard principles with the interesting fact that the staff and learning perspectives are more detailed than average. The strategic goal of the customer and market perspectives is customer satisfaction, including excellent nursing quality, information delivery to patients and service quality.

Nursing quality appears to be an operational goal, paired with different measures: individual nursing documentation and planning; and transposition of expert standards by nursing experts. Similarly, to the practice of Anglo-Saxon hospitals, nursing quality is a high-performance indicator where the community of patients and the building of this community are key focus areas. Additional operational objectives include the development of information transfer to the patients and to eliminate positions that are not filled up. Clinical management and financial perspectives propose a better economic performance through collaboration with customers, partners, staff and the general public [13-17].

Conclusions and Proposed Further Steps

Lessons learnt from the BSC adaptation into Hungarian hospitals

This paper has shown that the adaptation of the BSC planning method into the Hungarian regulatory and institutional framework could easily be applied and can be a basis for further dissemination. A proposed structure and content of the hospital strategic documentation can be seen in (Appendix 1).

This standardized method is likely to be appropriate as an overall strategic planning and implantation tool for rural and small specialized hospitals rather than big regional health centres. The elements of this method are composed of standardized environmental analysis, including stakeholder analysis, SWOT analysis, and satisfaction, setting strategic objectives based on the formerly defined mission statement and described vision of the hospital, creating so-called strategic map, developing performance and quality indicators which are strongly connected to the strategic objectives, and detailed action plan with sources, responsible persons (unit) and deadline of the implementation.

A further lesson learned from this study is the need for wide and careful involvement of the hospital staff already during the planning process. In this way, the person who will later be responsible for the implementation can become active actors in the development of strategic objectives, indicators and actions. This can hopefully contribute to the achievement of strategic objectives and to the successful implementation of the organizational strategy.

Proposed future steps about the dissemination of BSC based strategic planning and implementation

The extension of the BSC program to a national level would require approximately 2,5-3 years of work. This period would include the development of a strategic management organization by the National Healthcare Services of Hungary (ÁEEK) and preparing the project itself. BSC as a generic tool must be adapted to the nature of the given sector, in this case to the hospital sector. An advantage of the BSC is that it is flexible to suit any strategic setting [4]. Strategy creation can be designed in a structure similar to a pilot programme with the indicated 5-6 months’ lead time. Particular attention should be given to the implementation of the “top-down” principle during this project, in other words, the creation of territorial (regional or county) strategies must precede the preparation of institutional strategies.

A resource extension should be proportionally carried out based on the experiences of the pilot project. The extent of the involvement of external experts should be increased parallel to the number of hospitals which is especially important during the phase of strategic management development. On the other hand, the preparation phase of the project can be carried out with a smaller number of professionals. Permanent organizational units that are created during the national extension should take over the support team’s work to move forward to the BSC-based strategic management system automatically in the future.

(Figure 1) Pharmaceutical organizations put resources into the improvement and testing of their drugs including by financing clinical preliminaries. Moreover, pharmaceutical organizations additionally spend a lot of cash on publicizing. For example, in 2016 US $6.7 billion was spent on direct-to-buyer pharmaceutical publicizing alone in the USA [1]. Worldwide spending on medicines came to $1.2 trillion of every 2018 and will surpass $1.5 trillion by 2023, as per “The Global Use of Medicine in 2019 and Outlook to 2023” [2,3]. In spite of the fact that, entrance to essential medicines is hazardous for 33% of all people worldwide [4]. Restricted access to essential medicines (EMs) for treating chronic diseases is a noteworthy test in lowand middle-income countries (LMICs) [4,5]. Normal public part accessibility of even low-cost conventional medicines ranges from 30% to 55% crosswise over 36 LMICs [6]. Cost of drugs, antibodies, and diagnostics is a noteworthy weight in 105 middle income countries round the globe, containing 70% of the world populace, 75% of the poor [7]. While public hospitals offer free or subsidized treatment including essential medicines, the high patient caseloads, underfunding and wasteful medicine dispersion frameworks are boundaries to predictable administration arrangement [8].

Additionally, 90% of the populace in creating countries buy medicines all through of-pocket (OOP) payments [7]. Poor accessibility of medicines in the public part has pushed up household OOP use, making them the biggest household consumption thing after nourishment [9]. Non-communicable diseases (NCDs) which, as per WHO are currently the world’s greatest executioners. More than 36 million individuals kick the bucket every year (63% of global passings) from NCDs, essentially CVDs, cancer, chronic respiratory diseases and diabetes. Of these, 80% happen in LMICs [10]. Along these lines, The WHO has set at least 80% as objective accessibility of medicines for both communicable and non-communicable diseases in all countries [11]. Yet, Pharmaceutical organizations have a substantial want in creating drugs for chronic diseases and cancer treatments, because of high commonness, yet additionally because these drugs are regularly used in long haul [12].

Pharmaceutical licenses keep up medication costs well over the cost of creation and can limit access to required medicines [13]. Biotech drugs have totally changed the administration of a few diseases, including cancer and immune system diseases, for example, psoriasis, rheumatoid joint pain, multiple sclerosis, and inflammatory bowel disease [14]. The mind-boggling expense of biotech prescriptions (focus on a quality or protein and regularly are infused or infused, related with treating a chronic condition) frequently requires noteworthy OOP uses [15,16]. A few examinations state that pharmaceutical organizations value drugs monopolistically, secured by patent rights, while others accept that the high costs for vagrant drugs basically allow sedate R&D and creation costs. In any case, the global vagrant medication market is evaluated to contact US $209 billion by 2022 representing 21.4% of complete branded physician endorsed sedate deals [17]. As per the Tufts Center for Drug Development, it costs, by and large, $100 million out of 1975, around $900 million preceding 2004 and 1.3 billion after 2005 to build up another medication and put up it for sale to the public [18,19]. While, Scavone et al. [14] detailed that whole time that goes from the R&D stage until the medication’s advertising endorsement can last as long as 15 years, and it is portrayed by amazingly mind-boggling expenses, normally surpassing $1.2 billion [20]. Gouglas et al. [21] assessed at least $2·8–3·7 billion ($1·2 billion–$8·4 billion territory) for one immunization all the way to the finish of stage 2a among 11 pandemic infectious diseases [21]. Aside from the customary plan of RCT, lately further examination structures, including umbrella, container and stage preliminaries, were created and connected to new treatments, particularly in the zone of oncology look into [22].

Tay-Teo et al. [23] expressed the most normally acknowledged assessments of R&D costs, including cancer drugs, are between $200 million and $2.9 billion, after modifications for the likelihood of disappointment and opportunity costs [23]. Genomic studies directed in the previous two decades recognized the sub-atomic drivers of specific cancers and prompted the approach of focused treatments as a significant extra mainstay of the cancer treatment armamentarium [24]. As per the Global Oncology Trend Report, global spending on cancer drugs ascended from $75 billion of every 2010 to $100 billion out of 2014, 10.3% ascent in spending. Asia represents 60% of the world populace and half of the global weight of cancer [25]. There are more than 100 sorts of cancers, situated in various organs and sub-tissues and beginning from various cell types. Some cancer types (e.g., colon, bosom, and non- Hodgkin’s lymphoma) contain significantly increasingly explicit groupings dependent on their sub-atomic subtypes. In spite of this multifaceted nature and inconstancy, most sorts of cancer are treated with similar non-exclusive treatments [26].

Faultfinders guarantee that costs of creative drugs are over the top and contend that lowering costs won’t hurt the flourishing advancement. On the furthest edge, the pharmaceutical business demands that prohibitive valuing arrangements will detrimentally affect their capacity to produce advancement [27]. During 2017, PIVI worked with its nation accomplices and the WHO territorial and nearby workplaces to survey NITAGs fortifying needs and to give specialized help with 7 LMICs (Laos Peoples Democratic Republic, Mongolia, Vietnam, Armenia, Côte d’Ivoire; Moldova and the Republic of Georgia) [28]. In Europe, complete cancer tranquilizes deals dramatically increased somewhere in the range of 2005 and 2014, expanding from €8.0 billion to €19.8 billion [29]. Biologics were assessed to represent US$289 billion pharmaceutical deals in 2014 and are anticipated to reach US $445 billion of every 2019. It is additionally foreseen that a lot of global solution and OTC pharmaceutical deals will ascend to 26% by 2019 [30]. It is anticipated that new instances of cancer will increment from about 14 million of every 2012 to 22 million out of 2030, with most cases in LMICs situated in Africa, Asia and Latin America [31]. The anticipated increment in cancer frequency is anticipated to be most noteworthy in LMICs in Asia. In these countries, over 60% of the complete healthcare consumption originates from private assets, of which over 80% is immediate OOP payments, with disastrous outcomes for most families in these countries [25].

In India alone, upwards of 63 million individuals are constrained into poverty consistently, inferable from calamitous health costs, most of which are OOP payments for medicines [32]. Hereditary inclination, expanding future, urbanization, automation, insufficient health administrations and quick financial improvement powering stationary quality and changing dietary examples are adding to rising chronic disease trouble in the South Asian area [33]. Rijal et al. [34] detailed that Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, Maldives, Nepal, India, Pakistan and Sri Lanka, which are for the most part LMICs with provincial GDP per capita 1640 USD and home to a fourth of world populace [34]. As indicated by Giri et al. [35] bosom cancer was the most common cancer and fourth driving cause of cancer-related mortality among ladies in Asia [35]. Siegel et.al, 2019 states death rates in the least fortunate regions were 2-overlay higher than most prosperous provinces for cervical cancer and 40% higher for male lung and liver cancers during 2012-2016 [36]. 33% of the world cervical cancer weight is suffered in India, Bangladesh, Nepal and Sri Lanka. High-hazard HPV types were found in 97% of cervical cancers, and HPV-16 and 18 were found in 80% of cancers in India [37]. Stomach cancer (9·0%), bosom cancer (8·2%), lung cancer (7·5%), lip and oral pit cancer (7·2%), pharynx cancer other than nasopharynx (6·8%), colon and rectum cancer (5·8%), leukemia (5·2%), and cervical cancer (5·2%) are the main sorts of cancer in India in 2016 [38]. India has been outstanding in the global oncology network as the nation where cancer medication costs are less expensive contrasted with different countries. For example, the 4-week by week cost of trastuzumab was $2761 in India versus $6849 in the US [39]. It was to be sure encouraging to see that India paid $19000 for a 4-week course of bevacizumab (in view of acquiring power equality) while Australia paid just $543 [40]. In the US, people determined to have cancer are 2.7 occasions bound to bow out of all financial obligations, then people without cancer [41]. Saqib et al. [42] 2018 expressed that patients in LMICs think that it’s hard to manage the cost of non-biologics and their treatment with new restorative operators like biologic is practically outlandish. In this manner, the administration of cancer is genuinely influenced by the accessibility and affordability of anticancer operators [42]. Because of absence of data on relative medication costs and quality, it is hard for doctors to recommend the most efficient treatment. Absence of data on quality, non-accessibility and irreconcilable situations are additionally in charge of doctors not recommending the most affordable drug. The distinction in cost between the different brands of a similar medication shifts from 2-crease to more than 100-overlay in India [43]. Bhutan (13%), Maldives (5%) and Timor-Leste (5%) – are little countries with testing topographies that come up short on the limit with regards to nearby pharmaceutical generation. They may likewise use elective systems, for example, sending patients with cancer for treatment abroad [26]. Numerous instances of high medication costs exist and are often examined in the media. One regularly referenced model is imatinib (brand name Gleevec®), a medication for chronic myeloid leukemia, which significantly increased in cost after the US FDA allowed for another sign. Novartis raised its cost from $31,930 in 2005 to $118,000 every year in 2015 in spite of a gigantic increment in the volumes sold [44]. The nineteenth modification of the WHO EML in 2015 included 16 essential cancer drugs, including three staggering expense medicines, imatinib, rituximab and trastuzumab, and in this manner improving fair access to imaginative treatments for cancer that are generally inaccessible in low-asset settings [45].

India is one of the top global funders of R&D into disregarded diseases, as indicated by Thomas et al. [46] About 12% of medication, indicative, and immunization candidates for ignored diseases in the R&D pipeline are from India [46]. Most South Asian countries have very much spread out administrative pathways for biosimilar endorsement. While no biosimilar insulin is affirmed in USA as of date August 2015, the European Medicines Agency and Japanese medication administrative experts have offered endorsement to just a single insulin-a biosimilar insulin glargine delivered by Eli Lilly [47]. One of the most noteworthy wellbeing worries with biosimilars is the potential danger of safe based unfavorable responses. Because of their atomic size, biologics can legitimately actuate against medication antibodies which may have critical ramifications for both wellbeing and viability [48]. As makers of biosimilar items don’t approach the phone line and strategy of reference item, the assembling procedure may change marginally, yet this may have huge effect on the natural capacity of the item, including immunogenicity, possibly influencing the security and viability profile [49]. Likewise, the costs of medication dispersion in India are 2 to multiple times more prominent than in the United States or the European Union, in spite of immeasurably lower work costs.

Their staff are not required to indicate aptitudes in pharmaceutical warehousing and the executives, regularly with tragic results [50]. The month to month medication costs were the most astounding in the U.S and lowest in India. Be that as it may, regardless of having the lowest medication costs, drugs were the least reasonable (affordability evaluated as medication costs separated by GDP per capita or normal compensation) in India [39,40]. Those drugs that guarantee fix ought to be given the main need. The administrations and strategy producers in LMICs ought to organize access to profoundly successful biotech drugs used in therapeutic setting and cutoff spending on costly yet insufficient or insignificantly viable drugs used in palliative setting. Bury joint efforts between the BRICS countries like Brazil, China and India need to establish the tone and make more motivating forces to build nearby generation of drugs with LMICs [51]. There are different mediations or changes in approaches exhorted that can help in lowering the cost of biotech drugs like breaking the syndication in medication makers, changing the administrative rules by government offices for those organizations which production less expensive drugs and making the new medication endorsements quicker, expanding the cost adequacy proportion of drugs, accomplishing a harmony between doctor self-governance in recommending biotech drugs and costs caused by patients, empowering non benefit nonexclusive organizations which assembling biotech drugs by giving them charge motivating forces and different measures, esteem based repayment by restorative insurance agencies.

To Know more about Juniper Online Journal of Public Health

Click here: https://juniperpublishers.com/index.php

No comments:

Post a Comment