Annals of Social Sciences & Management Studies - Juniper Publishers

Abstract

Haitian officials, in line with most country leaders around the world, announced a series of health, hygiene and safety precautions following the COVID-19 global pandemic early in 2020. The tiny nation (10,714 square miles) situated on the island of Hispaniola, still recovering from the devastating 2010 earthquake, which claimed the lives of close to two hundred thousand people, seemed prepared to take on the challenges of COVID-19. Businesses and schools immediately closed, face masks and hand sanitizers were distributed by the thousands. But the effects of emergency injunctions that were not geared towards capacity-building, but rather prevention of rapid infectious disease transmission, could prove debilitating for the impoverished nation over the long-term. Primary and secondary school enrollment rates in Haiti are at an all-time low, and projections for the Haitian economy are dismal (-3.5% GDP growth 2020f) (World Bank 2020: 27). As a retrospective study, this paper conducts a critical quantitative and qualitative analysis of humanitarian aid, gender-based violence, and urbanism in Haiti, revealing that gender-responsive planning has a greater role to play in state-led disaster management plans and procedures for achieving long-term equity and sustainable economic growth.

Keywords: Urban informality; Gender-Based Violence (GBV); Gender-Responsive Planning; Humanitarian aid; Earthquake; Haiti

Research Article

Le Nouvelliste reported that emergency units at l’Hôpital de l’Université d’État d’Haïti (HUEH) (State University of Haiti Hospital) were overwhelmed by the COVID-19 pandemic in early spring 2020. With no quarantine units at HUEH and only 37 of 124 ICU beds nationwide meeting international ICU standards for a country of more than 10 million people [1], critical care units could not meet testing and treatment requirements of COVID-19 patients. How was it possible that nearly a decade after receiving more than 300 million USD from intergovernmental agencies for capacity-building projects, the Haitian healthcare system was operating with only 37 ICU beds? Following the January 12, 2010 earthquake, the Interim Haiti Recovery Commission (IHRC) was established to manage the implementation of aid programs in Haiti. Operating with over 300 million USD in funding from the U.S. government, the IHRC, co-chaired by the Government of Haiti (former Haitian Prime Minister Jean-Max Bellerive) and the UN Special Envoy to Haiti (former U.S. President William J. Clinton), had as its mandate: 1) Creation of new jobs in textile and manufacturing; 2) Support for people with disabilities; 3) Development of microfinance opportunities for small businesses; 4) Expansion of the Haitian public education system with support from the Inter-American Development Bank (IADB) and USAID; 5) Resettlement of displaced persons; and 6) Major debris removal [2,3]. When the IHRC’s mandate expired on October 21, 2011, little progress was made on the aforementioned. During the tenure of the IHRC, limited attention was given to soft infrastructure—the political and social systems in Haiti, weakened by decades of political instability and violence—and the important role that Haitian women have played in Haiti’s critical care and rebuilding processes.

Gender-responsive planning calls for a defined gender-focused plan or system that includes the linkages between public policies, resources, social capital, and gender [4]. Gender-responsive planning, policies, and approaches can include measures that take into account the special needs of women and girls in health care delivery and access; enhanced provisions for women in negotiating land use agreements; and guidelines for protecting women and girls under the judiciary and police force [5]. This article is a study on gender-responsive planning in a post-disaster context through an analysis of intergovernmental and non-governmental agencies and their partial successes and failures in Haiti. Ultimately, this work offers a framework for understanding the multiple impacts of urban informality and gender-based violence (GBV); and theoretical approaches for managing weak state failure and aid effectiveness through gender-responsive planning.

Urban Informality in International Development

Urban informality and informal economy are the byproducts of prescriptive and reactionary state and inter-organizationled economic and social reforms. Structural adjustment reforms forwarded by the World Bank and IMF as solutions to poverty and debt promoted liberalization and privatization schemes throughout the 1980s and 1990s in Latin America and the Caribbean, Asia, and Africa. Structural adjustment reforms enticed new investments in manufacturing and cheap labor to meet the demands of international trade and quick output. However, economic deregulation also meant lowered wages and limited social protections, forcing many households into poverty and the rapid urbanization of cities unprepared to meet the basic needs (water, sanitation, housing) of poor, rural, migrants in search of jobs in cities. Urban informality soon translated to people adapting to life in impoverished conditions outside of formal laws or sanctions. Some development economists like Hernando De Soto [6] might celebrate urban informality as a reflection of human agency and innovation amidst poverty, political oppression, and instability. While other international development theorists might point out that urban informality raises issues related to exclusion from formal markets and distributive justice—who gets to own property and who does not? [7]. Examples of urban informality include informal housing subdivisions in the Global South, like tent cities in Haiti, squatter settlements in India, or favelas in Brazil—that although formed through cooperative land agreements between individuals and families over decades, remain in violation of land use laws. Extralegal transactions in urban informal economies are frequently conducted under the auspices of formal state officials, who sometimes participate in informal markets for their own benefit. In Pakistan, “Karachi middlemen” serve as informal intermediaries between poor migrants, squatters, shopkeepers, and local authorities [8]. In the late 1940s, Karachi experienced a swell in rural-urban migrants, partly because of rapid growth in Pakistan’s textile and manufacturing industry promoted under the Colombo Plan in 1951 for the Asia-Pacific region and Pakistan’s Five-Year Plans, installed under the first Prime Minister of Pakistan Liaquat Ali Khan in 1948 (ending around 1998-1999). Where city and state officials were not financially or politically equipped to deal with major shifts in population demographics, housing and employment demands, middlemen came into play [8]. Middlemen would meet the needs of low-income migrants in Karachi, by collecting subsistence payments. These payments were then exchanged through bribes or pay-offs for “rights” to create and manage informal settlements and activities around the city [8]. While the activities of modern-day middlemen have shifted to meeting the consumerist aspirations of Karachi’s growing middle-class, the continued influence of middlemen as community stakeholders reinforces the idea that urban informality produces both positive and negative externalities within middle and lowincome state development.

The amalgamation of poor migrants and limited formal employment opportunities, peri-urbanization, privatization during the 1980s under El Gran Viraje (The Great Turnaround), work stoppages, and public strikes created Venezuela’s presentday barrios, or urban informal settlements that are now permanent fixtures across the principal city of Caracas. With President Chavez’s election in 1999 and social policy reforms implemented under his administration, rates of poverty, extreme poverty, and households in poverty saw an overall decline in Venezuela: “the percentage of households in poverty declined by more than half, from 54 percent in the first half of 2003, to an estimated 26 percent at the end of 2008” [9]. Yet, the aftershocks felt from repeated coup attempts (1992; 2019) have left the oilrich nation still struggling to manage a deep debt crisis and social unrest in the barrios.

Urban Informality in Haiti

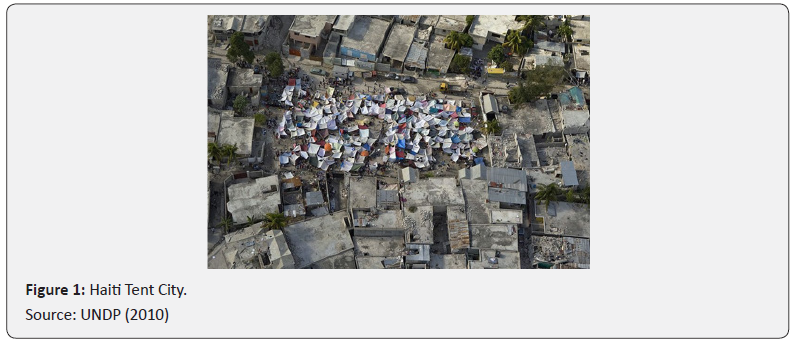

Well before the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic and 2010 earthquake, informal networks and informal aid substituted much of the core state planning operations in Haiti. Like Venezuela and Pakistan, urban informality in Haiti (Figure 1) was largely the outgrowth of structural adjustment reforms instituted in the 1980s and 1990s by the World Bank and IMF, which encouraged decentralization and privatization of public goods and services [10]. Peri-urbanization, tent cities, shadow police forces, and extralegal transactions for transport (tap taps), housing, and food comprise urban informal economy in Haiti. A 2002 report from the World Bank Report posed the question: “Is Haiti a decomposing state?” “Est Haïti un état en decomposition?” The short answer from the authors was no. The longer conclusion was that poverty, informal economy, political instability, limited health and hygiene services, informal unemployment and a weak judiciary system made funds for poverty reduction ineffective, and Haiti susceptible to persistent economic decline.

Informal Economy

Urban informality in Haiti operates as a socio-cultural informal sub-economy with domestic and international informal actors managing violence, cultural and social customs, and abject poverty. Haiti’s informal actors can be likened to “informal street-level bureaucrats”—who relying on trust, loyalty, and reciprocity build formal ties with local officials to meet demands such as food, health care, and housing in the community. Michael Lipsky’s pioneering work on street-level bureaucrats in Streetlevel Bureaucracy: Dilemmas of the Individual in Public Services [11] posited that street-level bureaucrats exercised a great level of discretion over the implementation of public policies. A social worker, for example, enrolling clients into health care plans or unemployment insurance at a one-stop center in the United States must determine client eligibility through assessments and interviews. In the absence of a strong state apparatus, informal street-level bureaucrats make similar determinations, but operate with higher transaction costs because of the heightened likelihood of misinformation, corruption, and lack of social insurance or protection.

Haiti’s “informal street-level bureaucrats” were present in the days, months, and years following the 2010 earthquake, managing donations, housing, and security around tent cities. After the 2010 earthquake, nearly 40% of residents in temporary camps reported receiving informal aid, like cash remittances, from informal sources like relatives and friends—not government agencies or local authorities—while 32% received no material assistance at all [12]. Formal assistance came in the form of donated tents and tarpaulins from agencies like the World Bank, the Red Cross, Catholic Relief Services, Islamic Relief, and Doctors Without Borders [12].

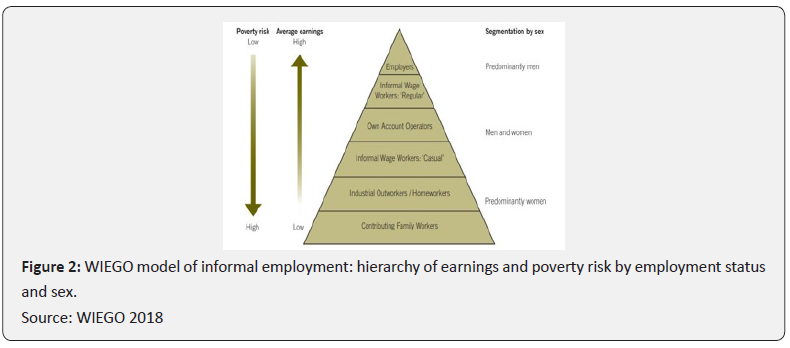

Aid in the form of cash remittances is common in developing countries: “In 2018, over 200 million migrant workers sent $689 billion back home to remittance reliant countries, of which $529 billion went to developing countries” [13]. Aid from “home” through informal channels is perceived to be more reliable, cheaper, and under less public administrative scrutiny. A 2003 survey on remittances in South Africa found that “remittances up to R250 to neighboring countries cost R25 and R50, through friends and taxi drivers, respectively, as compared with over R100 through registered banks and over R80 through money transfer agents like MoneyGram and Western Union” [14]. Informal aid remittances have also driven the development of mobile banking technology in the Caribbean, Asia, and Africa as the preferred channel for informal cross-border remittances, which increased to 51.8% in 2015 [15]. Remittances to Haiti via formal channels reached 3.3 billion USD in 2019, almost 37% of the country’s GDP [16]—unrecorded transfers of money through couriers though are projected to be higher [17]. The overall trend towards informal aid remittances over the past two decades reflects a growing Haitian diaspora and new technologies, outside of traditional banking, that have facilitated informal aid assistance. Informal economy through aid remittances however provides no viable opportunities for formal employment or investment back into the local economy. Rather, low wage workers in the informal sector—especially women, employed as domestic workers, waste pickers or street vendors—are subject to higher incidences of economic and physical violence in abusive workplaces (Figure 2). Occupational gender segregation in the neoliberal era reflects a gendered provisioning of goods, services and labor—or what economist Nancy Folbre [18] calls “economies of care” that are poorly regulated.

In Haiti, irregular and informal work has exposed women to workplace violence and economic hardship with limited alternative options. Surveys from the Haitian Institute of Statistics and Information Sciences (IHSI) between 1990 and 2000 showed that structural unemployment in Haiti was due in large part to the prevalence of low skilled informal work and occupational gender segregation. Women made up 60.7% of the unemployed population, and men 43.1% [19]. Nearly 44% of all households were female headed households, with women and girls employed in the informal sector to varying degrees as cooks, nannies, or housekeepers [19]. Young Haitian women and men seeking new formal employment opportunities were often recruited through informal channels to work in “bateys,” or sugar mill camps, in the Dominican Republic, under the guise that they would eventually receive formal citizenship status and economic rights as regular wage earners. However, work in the bateys is typically dangerous and laborers are often given fraudulent working papers that make it almost impossible to regularize their status as agricultural employees.

Gender-Based Violence (GBV) and Urban Informality

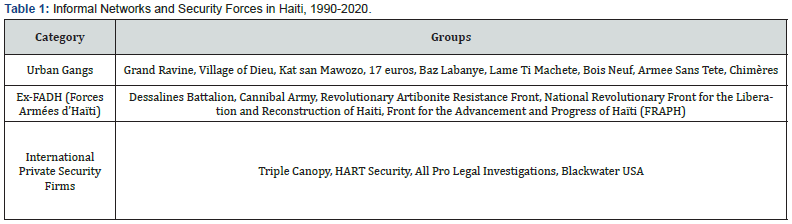

The 2006 film Ghosts of Cité Soleil, which introduced the world to “Lele” Senlis, a French aid worker, and the leaders of Chimères “Ghosts,” a notorious gang in Haiti’s Cité Soleil slum, revealed the prominence of contemporary urban gangs in Haiti. In the months following the 2010 earthquake in Haiti, international private security officers, urban gangs like the Chimères, and ex- FADH (Forces Armées d’Haïti—FAd’H) paramilitary units took to patrolling Haiti’s tent cities and surrounding neighbourhoods (Table 1) —sometimes in concert with, or compensating for the Haitian National Police (HNP), already strained from limited funding and tensions from political violence [20]. Informal security networks and private security firms attending to foreign dignitaries and UN peacekeeping forces committed or ignored acts of gender-based violence in Haiti after the 2010 earthquake. Doctors Without Borders reported treating two hundred and twelve survivors of sexual and gender-based violence (GBV) five months after the January earthquake [21,22]. The United Nations Stabilisation Mission in Haiti (MINUSTAH), which ended its thirteen-year mission in Haiti in 2017, came under fire for accounts of sexual abuse involving Haitian children. Research studies published in 2019 found that MINUSTAH personnel had fathered hundreds of children, nicknamed Petit-MINUSTAH, “little MINUSTAH,” with Haitian women and adolescents. Some families had also received small allowances for child rearing from MINUSTAH officials [23,24]. Instead of focusing on the underlying causes of GBV in tent cities linked to informal security personnel, and the spread of misinformation stemming from poor social and economic supports, the IHRC, MINUSTAH, and other UN agencies continued to argue that poverty, prostitution, and living conditions in tent cities were to blame for the increase in rates of GBV. In a January 16, 2011 press release, CEO of the UN Foundation, Kathy Calvin wrote, “[Camp residents] need lighting so that women and young girls can feel safer when walking to the latrines… That is why the United Nations, the UN Foundation, and other partners are distributing solar-powered lights to camps” [25]. Solar powered lights, while well-intentioned, were a band-aid solution to the systemic violence, corruption, and mishandling of GBV incidents throughout Haiti’s tent cities and slums. Managing urban informality and GBV in Haiti’s tent cities would prove pointless, so long as root-cause factors like systemic exclusion of Haitian women’s organizations and misreporting of data, budgets, and GBV were not addressed.

Gender-Responsive Planning

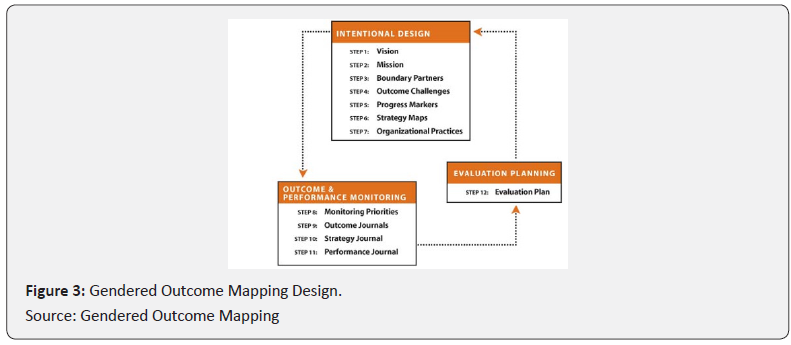

The unplanned and unplannable are frequently the outcomes of unequal power relations expressed through state action or inaction. Gender-responsive planning (Figure 3) as a mechanism for state intervention, stresses a critical overhaul of country assessment plans to include sex-disaggregated data, time use studies, and strategic gender needs alongside practical gender needs. Consensus on gender-responsive planning as a quantitative and qualitative methodological approach to state planning, monitoring, and evaluation plans grew out of the 1995 Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action. The Platform reaffirmed the “human rights of women and of the girl child as an inalienable, integral and indivisible part of all human rights and fundamental freedoms” (1995 Beijing Platform for Action: 2). The Platform also urged government leaders to:

Gender-Responsive Planning The unplanned and unplannable are frequently the outcomes of unequal power relations expressed through state action or inaction. Gender-responsive planning (Figure 3) as a mechanism for state intervention, stresses a critical overhaul of country assessment plans to include sex-disaggregated data, time use studies, and strategic gender needs alongside practical gender needs. Consensus on gender-responsive planning as a quantitative and qualitative methodological approach to state planning, monitoring, and evaluation plans grew out of the 1995 Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action. The Platform reaffirmed the “human rights of women and of the girl child as an inalienable, integral and indivisible part of all human rights and fundamental freedoms” (1995 Beijing Platform for Action: 2). The Platform also urged government leaders to:

Analyse, from a gender perspective, policies and programmes - including those related to macroeconomic stability, structural adjustment, external debt problems, taxation, investments, employment, markets and all relevant sectors of the economy - with respect to their impact on poverty, on inequality and particularly on women; assess their impact on family well-being and conditions and adjust them, as appropriate, to promote more equitable distribution of productive assets, wealth, opportunities, income and services…(g) Provide adequate safety nets and strengthen State-based and community-based support systems, as an integral part of social policy, in order to enable women living in poverty to withstand adverse economic environments and preserve their livelihood, assets and revenues in times of crisis; (1995 Beijing Platform for Action: 20-21)

Substantial scholarship on applied approaches to genderresponsive planning support the 1995 Platform for Action. Caroline Moser’s triple roles theory [26] and Naila Kabeer’s Social Relations Approach (2005) for example provide a conceptual framework for understanding gender-responsive planning as the “interrelationship between agency, resources, and achievements” and power sharing (Kabeer 2005: 15). Moser’s triple roles theory describes how women are simultaneously reproducers, community managers and wage earners [26]. Kabeer’s Social Relations Approach explains that “social relationships…govern access” to resources, labor, time, and services (Kabeer 2005: 13). This scholarship has helped advance a greater understanding of the consequences of transnational families, transnational motherhood, social capital, female headed households, division of labor, and female migrant networks. UN agencies have endeavored to improve research on unpaid care work and the socioeconomic contributions of women and girls in low- and middle-income countries. Additionally, the push for more sex-disaggregated data and time use studies through gender-responsive planning over the past two decades has created a new field of opportunities for critical research and intervention from NGOs and non-profits around the world. In the Republic of Korea, researchers found that unpaid care work was “equivalent to 4,407% of the value of paid care work” [27]. On transnational families and public security, the Romanian NGO Alternative Sociale determined that when mothers migrated, despite a private care market of babysitters, tutors, and surrogate care takers, there was still an increase in rates of school absenteeism and dropouts [28]. This research has encouraged the creation of new programming in education, maternal care, food security, and criminal justice to support women, parents, and girls globally.

Creating Opportunities for Gender-Responsive Planning in Haiti

Sociocultural Factors

Sociocultural factors have played an important role in shaping how officials, citizens, and institutions in Haiti document and respond to GBV, complicating traditional gender-responsive planning methods and approaches. Women in certain trade unions and industries cited sexual harassment from peers and supervisors, but many victims were either reluctant to report the harassment or reports were disregarded by authorities as “hearsay” [19]. Fear of reprisals, pressure, stereotypes, and prejudice from the victim’s family or the perpetrator’s family were also factors that impacted reporting and accountability on GBV. A 2016-2017 “Mortality, Morbidity and Use of Services Survey in Haiti” Enquête Mortalité, Morbidité et Utilisation des Services en Haïti (EMMUS) for instance found that of the 14,371 Haitian women surveyed between the ages of 15 and 49, more than 54% never sought out help or spoke to anyone about incidences of emotional, sexual or physical violence (EMMUS 2018: 17). Uneducated and poor Haitian women were also less likely to receive information from clinics on STDs and HIV/AIDS prevention and to negotiate protected sex with partners, increasing the likelihood of “survival sex” and other risky behavior [19] Of the approximately 150,000 adults living with HIV/AIDS in Haiti, 87,000, or 58% were women in 2018. New infections were more prevalent among young women between the ages of 15 and 24—1600 new HIV/AIDS infections in 2018 were among young women, less than 1000 new infections were reported among young men (UNAIDS 2018).

Structural Factors

Building on momentum from the 5-year plan (2006-2011) established by the “Concertation Nationale Contre les Violences Faites aux Femmes,” “National Convention Against Violence Against Women” organized by the Haitian Ministry of Women’s Affairs, the Haitian Ministry of Health, and Prime Minister Gérard Latortue, Haitian women’s organizations attempted to join programming efforts of the UN GBV Sub-Cluster post-earthquake [29]. However, their attempts were blocked by the UN GBV Sub- Cluster [21]. In a joint report to the UN Human Rights Council in April 2011, the international human rights organization, MADRE, in partnership with Commission of Women Victims for Victims (KOFAVIV), Women Victims, Standing (FAVILEK), and National Coordination for Victims Direct (KONAMAVID) produced a report titled “Limited Access to Medical Services, Lack of Adequate Security in the Camps or Police Response, and the Exclusion of Grassroots Organizations” on the alarming situation of GBV in Haiti post-earthquake [21]. MADRE and its collaborators also argued that rejecting Haitian women’s groups violated the Inter-American Convention on the Prevention, Punishment and Eradication of Violence Against Women (“Belém do Pará”), UN Security Council Resolution 1325 and the UN Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement.

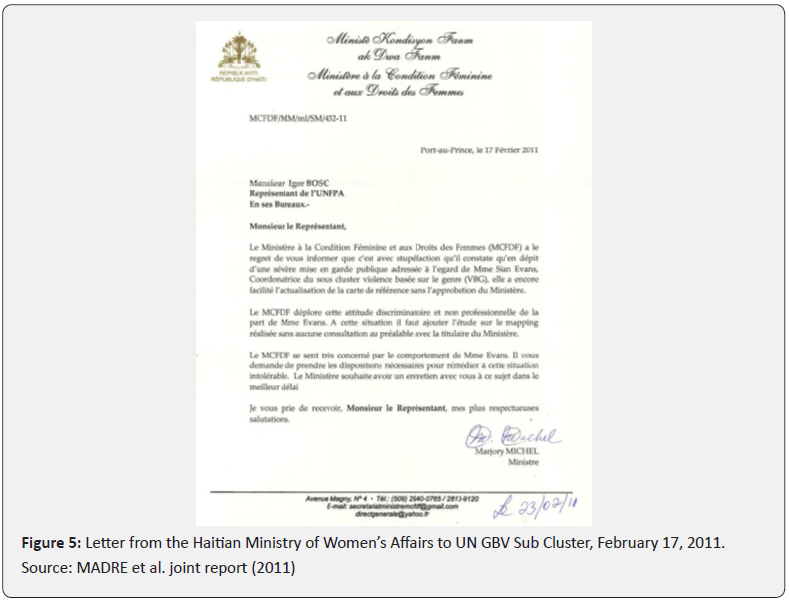

In a letter from the Haitian Ministry of Women’s Affairs to the UN GBV Sub Cluster dated February 17, 2011, Minister of Women’s Affairs Marjory Michel decried the deplorable conditions of Haitian women and girls in tent cities—noting limited UN support for women and girls on the ground and exclusion of Haitian women’s organizations from UN planning and procedures post-earthquake (Figure 4). However, with almost no accountability measures in place to ensure transparency or a formal response, the letter was ignored by the UN GBV Sub Cluster [21]. Reported feelings of disrespect and mistrust set the tone for many of the negotiations and meetings amongst Haitian and foreign leaders following the 2010 earthquake—with even President René Préval lamenting, right after the earthquake, that the only people who seemed to be with him were journalists trying to snap pictures of dead bodies [30]. The crisis of leadership in Haiti had a direct impact on the limited interventions of the IHRC. Early on, the IHRC 2010 Project Proposal, responding to the concerns of grassroots women’s organizations, had in fact integrated a section on “Protection, Care and Support for Women who are Victims of Violence in Haiti.” But the proposal suffered from three key omissions: 1) a funds disbursement strategy for the 10.6 million USD budget 2) an actionable timeline with steps towards GBV prevention programming 3) Haitian partners or NGOs that could assist with program implementation (Figure 5). Weakened by organizational mismanagement, and funds directed towards other immediate crises (like food, medicine, and sanitation), the IHRC ended its mandate as a missed opportunity to develop new institutions or programs in education and health care that could have benefitted Haitian men, women, and children past the 2010 earthquake.

Socio-political Factors

In the years before the 2010 earthquake, Haitian women and Haitian women’s associations were severely underrepresented within the legislative bodies of the Haitian government and administrative positions of power. In “1990, the number was down to 34 elected women: five as mayors, 17 as second member of the Board and 12 as the third member. In 1997, only 6 of the 127 mayors were women. In 2000, there was a slight increase, with 25 women being elected mayors in four Departments” [19]. In the 2015-2016 elections, the Institute for Justice & Democracy in Haiti reported that women still remained underrepresented in politics: “In the August and October, 2015 elections, 22 out of 232 senatorial candidates were women (12 percent)…Of the Chamber of Deputy candidates, 129 out of 1621 were women (8 percent)” [31]. Political activist and economist, Myriam Merlet who died in the 2010 earthquake, argued that generally structural sexism made it difficult for women to consider political careers in Haiti. According to Merlet, systemic biases, women with lower levels of educational attainment, and widespread beliefs that politics are too “dirty” and dangerous for women contributed to low rates of political participation [32]. To overcome structural sexism would necessitate a greater focus on strategic gender needs at all levels in government, health care, economy, and society. Whereas practical gender needs are based on survival—“a response to an immediate perceived necessity” “formulated from the concrete conditions women experience” [33]—strategic gender needs refer to power relationships in the delivery of health and human services.

Strategic Gender Needs

Oftentimes, practical gender needs attract more attention and funding during crises and disasters since they relate to human survival. However, strategic gender needs are “those needs which are formulated from the analysis of women’s subordination to men, and deriving out of this the strategic gender interest identified for an alternative” [33]. Formal state officials mediate strategic gender needs “between state and civil society…within the family between men, women, and children”, which “has critical implications for the identification of the ‘room to manoeuvre’ to address strategic gender needs” [34]. Feminist epistemologies on planning and ways of understanding gender through social positioning compel a greater consideration of location, power, and the lived, relational experiences of men, women and children—to the extent “that practical gender needs only become ‘feminist’ if and when transformed into strategic gender needs” [33]. Stateapproved programs on women’s policies encourage the notion that a state agenda on “feminism” does have a place in public, political, popular discourse. Strategic gender needs move past binaries of “survival-necessity” to state-led initiatives and public programming on gender equality.

Implementing Strategic Gender Needs in the Haitian Context

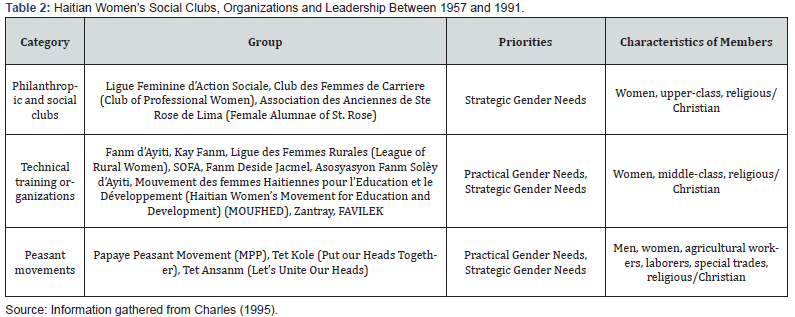

“State feminism” in Haiti was most visible throughout the Duvalier regime between 1957 and 1971. The Duvalier propaganda machine engaged women through political narratives like the “Marie Jeanne”—daughter of the revolution [35]. This increased politicization turned women from “political innocents” to “political agents” –which not only created a new role for upwardly mobile middle- and upper-class Haitian women in Haitian society and economy, but also unleashed a wave of terror against both men and women, considered enemies of the state [35]. In 1986, several weeks after the overthrow of Jean-Claude Duvalier (Baby Doc), who succeeded his father Francois Duvalier (Papa Doc) in 1971, thirty-thousand women, represented by over fifteen women’s organizations, assembled in Port-au-Prince to demand their inclusion in the newly formed democratic Haitian government [35]. In fact, theirs was the first demonstration following the overthrow of the Duvalier government. Haitian women were, as Myriam Merlet remarked, “[Revolting] against exclusion. The country was being remade and we didn’t want it to be remade without us ‘nou pa t vle peyi a ta refet san nou’ [36]. Grassroots pressure led by women’s organization in the 1980s led to new provisions for strategic gender needs. The Haitian Constitution in 1987 established new articles related to gender equality. Articles 16, 17 and 18 of the 1987 Haitian Constitution define citizenship as “the combination of civil and political rights … ‘all Haitians regardless of sex or marital status, who have attained eighteen years of age, may exercise their political and civil rights’ …‘Haitians shall be equal before the law, subject to the advantages conferred on native-born Haitians who have never renounced their nationality’” [37]. In the early 1980s, women’s groups grew alongside the Haitian government transitioning from dictatorship to democracy, representing a cross-section of goals and interests related to advancing women’s rights, housing, education, and workplace equality (Table 2). Some traditional women’s clubs, such as the Ligue, the Club des Femmes de Carriere (Club of Professional Women) focused on philanthropic efforts to raise awareness on promoting gender equality in the workplace and higher education [33]. Other groups, such as Fanm d’Ayiti, Kay Fanm and Ligue des Femmes Rurales (League of Rural Women), focused on practical gender needs, or “survival issues,” such as food and shelter. There were more groups like the Association des Anciennes de Ste. Rose de Lima (Female Alumnae of St. Rose) that offered a range of services that met both strategic and practical gender needs like training centres on healthcare for women and children, and education services for the poor [33]. Additional women’s groups that were active between 1987 and 1991 included associations like SOFA, FAVILEK, Fanm Deside Jacmel, Asosyasyon Fanm Solèy d’Ayiti, Mouvement des femmes Haitiennes pour l’Education et le Développement (Haitian Women’s Movement for Education and Development) (MOUFHED). These organizations soon coalesced into a powerful lobby in Haitian government. In 1990, the Lavalas Movement, the party platform for Haiti’s first democratically elected President, Jean-Bertrand Aristide, received the support of many women’s organizations [33]. Eight months after Aristide’s election though, a military-led coup d’état in September 1991 overthrew his presidency [10]. The women’s organizations that once flourished alongside the fledgling Aristide presidency and promises from the 1987 Haitian Constitution, quickly descended into turmoil. After the 1991 coup, paramilitary forces targeted organizations that promoted gender equality, burning down offices and destroying homes of suspected Aristide sympathizers [33]. In 1999, the UN Special Rapporteur on Violence Against Women, Radhika Coomaraswamy observed that “following the military coup d’état, Haitian women continue to suffer from …‘structural violence’, targeted at the most vulnerable and poor…between November 1994 and June 1999, the Ministry of Women’s Affairs and Women’s Rights registered 1,500 cases of girls between the ages of six and 15 who had been the victims of sexual abuse and aggression” [38]. In 1994, backed by a United Nations Security Council Resolution, Aristide returned to Haiti as president and established the Ministry for the Status of Women and Women’s Rights (MCFDF) (Ministry of Women’s Affairs) to address the socioeconomic status of women in Haiti. In alignment with the 1995 Beijing Declaration, the MCFDF designed the following platform: “Conceiving, developing and implementing a policy of equality between men and women based on dissemination of the gender perspective or analysis of social relations between men and women… Boosting the political role of the MCFDF within the State apparatus… Taking specific steps to promote and defend women’s rights.” [19] Plans for a gender-based assessment of budgets and expenditures were also in progress under the MCFDF, alongside campaigns for more women in elected office. However, a second coup in 2004, sent Aristide permanently into exile in South Africa, and left MCFDF close to dissolution. In the years after the 2004 coup in Haiti, there was a resurgence of violent attacks on women and girls. Reports published in The Lancet estimated that between February 2004 and December 2005, 19,000 per 100,000 girls were raped in Port-au-Prince [39].

State Violence and GBV

GBV as an instrument of pacification campaigns, state conflict, and warcraft has long been part of country rebuilding and wartime narratives. During the “Rape of Nanjing” between 1937 and 1938 for example close to 20,000 women reported being raped in China. Janjaweed militias in Sudan have commanded gender-selective killings of millions since the early 2000s. In Brazil, military occupations of favelas Complexo do Alemão and Vila Cruzeiro under “pacification police units” leading up to the World Cup (2014), have led to thousands of unreported deaths, rapes, and kidnappings. On GBV and state violence in Haiti, Duramy’s [40]. extensive study found that the effects of French colonization and slavery could still be felt in the country—as skin color, dialect, gender, and property ownership play a significant role in exposure to and experiences of violence, starting at an early age. It is with great difficulty though that the experiences of GBV survivors, men, women, and children, are accounted for in tribunals, commissions, or peacekeeping operations—not for lack of technical expertise on the part of mediators, activists, and other practitioners, but for lack of political will. Gender-responsive planning in state development has occupied a marginal role in war tribunals, economic development, and state planning, because it often calls for perpetrators of GBV, and other corrupt and incompetent officials to face prosecution, exile, or sanctions. Often, these perpetrators are politically well-connected or hold military rank.

Conclusion

At a 1986 meeting on the status of Haitian women, Haitian human rights activist and scholar Suzy Castor declared: “During the long political life of Haiti as a nation, the contributions of women to the struggles against the oligarchy and for democracy were significant. Yet, their political roles have not been recognized. Like all the other ‘subalterns’ their history has been obscured. There is an historical erasure of [woman’s] condition” [33]. This erasure is intentional, owing to the legacies of postcolonialism, neoliberalism, and the culture of foreign aid dependency in Haiti and the rest of the Global South. Haitian history, in its ebbs and flows, has seen surges and declines in the visibility and participation of women in society and economy. With limited mechanisms to predict or even forecast natural disasters, pandemics, and armed conflict, greater attention must be paid to equity, instead of pre-emption in state planning. Equity in public policy administration and practice would resemble government bodies adopting methods to redress grievances while strengthening laws for accountability and transparency. Paul Collier’s Bottom Billion [41] and Dambisa Moyo’s Dead Aid [42] are two influential works that have shaped debates on equity, paternalism, conflict, and global governance over the past decade [43-52]. Collier maintained that many developing countries fall into the “conflict-trap,” where political instability and violence from domestic coups foster corruption; while Moyo specifically denounced the complacency of African leaders, who for years neglected investing in domestic financial markets and civil society, instead relying on humanitarian aid to resolve national crises. Gender-responsive planning thus presents as an opportunity to integrate equity into law and state practice to strengthen community resiliency in times of conflict and distress [53-65].

To Know more about Annals of Social Sciences & Management Studies

Click here: https://juniperpublishers.com/asm/index.php

No comments:

Post a Comment