Gerontology & Geriatric Medicine - Juniper Publishers

Abstract

Objectives: Lack of knowledge about geriatric

conditions is a barrier that prevents older minority populations from

receiving optimal healthcare. We aim to develop an educational

initiative to improve the knowledge gap on cognitive dysfunction in

three target populations: older minority community members, their

caregivers, and healthcare professionals (HCPs).

Methods: A nested mixed-methods with an

interventional pre-post assessment approach was used for this

community-based educational initiative. Educational sessions on memory

loss were developed and conducted. 182 community members, 63 caregivers

and 133 HCPs participated. Pre-posttest questionnaires and qualitative

data were collected to measure the impact.

Results: The results showed significant

improvements in knowledge in all three participant groups. The

qualitative comments showed improved understanding and intentions to

change.

Discussion: Development of an educational

program on cognitive dysfunction targeting community members, caregivers

and HCPs who take care of older patients is feasible in underserved

community and clinical settings.

Keywords: Cognitive dysfunction Educational initiative Ethnogeriatrics Older minority populations

Abbrevations:

MCI: Mild Cognitive Impairment; HCP: Health Care Providers; HRSA:

Health Resources and Services Administration; MSK: Memorial Sloan

Kettering Cancer Center; GRIP: Geriatric Resource Interprofessional

Program; CBOs: Community-Based Organizations

Introduction

One important public health dilemma is the

multi-layer challenge associated with the care of the older adult,

specifically focused on cognitive health. The US population is getting

older and growing more racially diverse. The number of racial/ethnic

minority populations has increased from 46 million in 1980 to 83 million

in 2000, with an estimated increase to 157 million by 2030 [1].

Minorities and older adults represent an intersection of populations

that are particularly vulnerable to suboptimal care. The causes are

complex and focus on racial and ethnic disparities in health resulting

from socioeconomic status, unequal access to care, differences in

behavioral, environmental and genetic risk factors, and social and

cultural biases that influence the quality of care [2]. Moreover, ageism

tends to reinforce social inequalities as it is more pronounced towards

poor people or those with dementia [3]. An estimated 5.4 million

Americans have Alzheimer’s disease, and by mid-century, this number is

projected to grow to 13.8 million [4]. Today, someone in the US develops

Alzheimer’s disease every 66 seconds. By 2050, one new case of

Alzheimer’s is expected to develop every 33 seconds, resulting in nearly

1 million new cases per year [4]. Studies have shownthat more years of

education is associated with a lower risk for dementia [5]. It is no

surprise that dementia afflicts minority populations more than

Caucasians; African Americans are twice as likely, and Hispanics are

about one and one-half times as likely, to have Alzheimer’s or other

dementias compared to Caucasians [6]. Several barriers to addressing

cognitive dysfunction exist within both the older and minority

populations. These barriers include poverty, lack of transportation,

illiteracy, cultural taboos regarding dementia and poor communication

[7-9]. For example, in New York City (NYC), 23% of the population is

categorized as having low-English proficiency. Many people in the community with Mild Cognitive

Impairment (MCI) and Alzheimer’s disease do not recognize cognitive,

functional or behavioral impairment as abnormal [10]. This lack of

understanding can have serious effects on health, and because they or

their caregivers cannot recognize and acknowledge the deficits, they do

not seek treatment. Daily functioning may be compromised because they

lack adequate judgment of situations [11]. Enough education needs to be

given to those affected and to the community at large to aid in

preventive care and to improve understanding of early diagnosis and

disease management.

Caregivers play a crucial and physically, mentally and

emotionally demanding role in the management of patients with

serious chronic diseases. People with dementia typically require

more supervision, are less likely to express gratitude for the help

they receive and are more likely to be depressed. These factors

have been linked to negative caregiver physical and psychosocial

outcomes [12]. Family caregivers often feel unprepared to provide

care, have inadequate knowledge to deliver proper care, and

receive little guidance from the formal health care providers [13].

Family caregivers may not know when they need community

resources, and then may not know how to access and best utilize

available resources [14]. Without this support, caregivers often

neglect their own health care needs to assist their family member,

causing deterioration in the caregiver’s health and well-being

[15].Despite the growth in the older population, there is an unmet

need in healthcare workforce to take care of these patients’ needs.

While the demand for physicians specialized in the medical care of

older adults is increasing, the interest among medical students for

a career in geriatrics is slow to follow [16]. Though the coverage

of geriatric topics at medical schools is increasing, students still

express significant reservations about their abilities to treat older

patients. In one national survey, only 27 % of graduating familypractice

residents and only 13% of graduating internal-medicine

residents felt very prepared to care for nursing-home patients.

Although a large majority of graduating psychiatry residents felt

very prepared to diagnose and treat delirium (71%) and major

depression (96%), only 56% felt very prepared to diagnose and

treat dementia [17]. In this paper, we examine the role held by

three specific groups of people in the care of cognitive health

in underserved ethnically diverse populations: the older adult

community members themselves, their caregivers, and the health

care providers (HCP) taking care of them. Each role has significant

opportunity in improving knowledge and in understanding the

disease and its appropriate management. We focused our efforts

on a large-scale educational program to address these gaps in

knowledge, focusing on cognition in older adults, for all three

groups.

Methods

Team development

The Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA),

an agency of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services,

is the primary federal agency for improving health care to people

who are geographically isolated, and economically or medically

vulnerable. Through the Geriatric Workforce Enhancement

Program (GWEP), HRSA provides funds to improve the healthcare

of older adults through education and training. With the GWEP

award, the Geriatrics service at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer

Center (MSK) established the Geriatric Resource Interprofessional

Program (GRIP). The GRIP team serves as content experts and a

teaching core that includes representation from occupational and

physical therapy, pharmacy, nutrition, medicine, nursing, social

work, psychiatry, immigrant health and members from the GRIP’scommunity and clinical partners that serve community-dwelling

older adults in culturally diverse and medically underserved areas.

The community-based organizations (CBOs) and clinical sites are

experts in the populations they serve. Team members teach each

other about their respective professions, context, and its unique

relevance in the health management of the older adult during the

process of developing appropriate community, caregiver and HCP

educational material. Via GRIP, multiple professionals’ expertise

and perspectives are infused into one educational program

targeted for each audience.

Target population

We targeted three groups of learners: older community

members, caregivers, and HCPs. All participants were selected

by convenience sampling. Older adults were accessed through

regular attendance to community programs in the NYC area,

partnered with GRIP. The NYC boroughs of Queens and

Brooklyn were targeted for their ethnic diversity to cater to the

underserved. The borough of Queens in NYC is the most ethnically

diverse urban area in the US with 74% of the population being

Hispanic, African American or Asian and 48% being foreign

born. The borough of Brooklyn is about 34% African American,

13% Asian and 19% Hispanic or Latino with about 36% of the

population being foreign born [18]. The partner CBOs marketed

for the educational programs through phone calls, digital and

print advertising, and through in person reminders at other

educational programs. Caregivers were approached through CBO

staff who targeted invitations to this caregiver-client group. Digital

and print marketing were also utilized for the caregiver audience.

HCPs included residents and fellows in training, attendings,

nursing staff including nurse practitioners, and social workers.

Sessions for staff were conducted at scheduled educational

settings, like monthly staff training and conferences at NYC area

hospitals. Participation in the sessions and completion of related

assessments were voluntary and explained as such by site staff

with the help of interpreter(s) if needed.

Content development and implementation

Across all content development, the GRIP team used the

Patient Education Materials Assessment Tool -A/V (PEMAT)

[19] to rate the content’s understandability and actionability.

GRIP team members, including CBO representatives, provided

feedback to the presenter about content organization, language,

and engagement. Cultural responsiveness was discussed to

ensure attendees would be able to connect and identify with the

material and that the material was communicated in a culturally

appropriate way, accounting for traditions and norms around

aging and health.To understand the educational gaps of older community

members, regular attendants of our partner CBO educational

programs at senior centers, religious institutions, public libraries

and CBO headquarters completed an informal needs assessment.

Older community members were asked to rank the followingtopics on their interest level, on a scale from 1 to 4 (1 being their

first choice and 4 their last) on four listed topics: nutrition, falls,

memory loss and cancer. Thirty-five older adults responded to

this survey and 71% indicated memory loss as most interesting to

them. From this, the GRIP team focused initial efforts to develop

the memory loss and dementia program. In the Fall 2015, the

primary presenter, a geriatrician, developed the audiovisual

module Memory Loss & Dementia, for the community older adult

population. The material incorporated imagery that the target

audience could relate to, such as Yoga, ethnic foods and landscapes

for sessions developed for the South Asian communities. The

geriatrician presented the material to the GRIP team. Using the

PEMAT, GRIP team members rated the material and the scores

for understandability and actionability were 59% and 78%

respectively. The material was revised based on the feedback,

improving these scores to 83% and 90%. Five of the 8 lectures

were interpreted, 4 to the predominant South Asian language

(Hindi or Bengali) and 1 to Spanish. The remaining 3 lectures

were delivered to English speaking audiences.

To identify the educational needs and the interests of

caregivers, the GRIP conducted a 90-minute focus group. The

subject of memory loss was identified as a topic of interest. A

module called Caregiver Education: Cognitive Impairment was

developed. Per GRIP’s content development process, it underwent

a PEMAT review (83% understandability and 80% actionability),

with the presenter adjusting after the feedback regarding

organization, language and cultural responsiveness. Since most

caregivers identified as South Asian, 4 of the 7 sessions were

provided in English with simultaneous interpretation to the

predominantly understood language of the group, Hindi. Though

the majority caregivers were native Gujarati speakers, the most

commonly understood language in the group was Hindi. The

remaining 3 sessions did not need interpretation or translation as

it was to English-speaking audiences.

Given the well-documented shortage of appropriately trained

HCPs in the care of the older adults, the subject of memory loss/

dementia/delirium, was well-suited for our HCP target population.

Four modules were created to meet the needs of each types

and level of HCP audience: Delirium in Older Hospital Patients

(Post Graduate Year -PGY- 1-3), Assessment and Management

of Cognitive Impairment in the Older Adult (Interprofessional),

Cognitive Impairment in the Older Adult (Nursing), and Dementia

& Delirium (PGY1). In this large educational initiative across three

learner groups, between November 2015 and January 2019, the

following sessions were implemented: Memory Loss & Dementia

(older community members) was conducted 8 times at 7 different

centers. Caregiver Education: Cognitive Impairment was offered

7 times at 3 different centers (one being a video live-stream

program) for caregivers. The 10 sessions for HCPs comprised one

of the four modules described and were conducted in 5 different

sites.

Measures

This study was conducted as a nested mixed-methods pre-post

intervention design to incorporate quantitative pre and post data

and qualitative data after the intervention to assess its effectiveness

(20). Questionnaires were developed to assess knowledge uptake

after participation. They contained five to six multiple choice

questions and were translated to multiple languages. They were

administered prior to and immediately after participation in the

educational program. Pre- and post-questionnaires were matched

using an identification case number. In August 2018, the pre-post

questions for community members were modified to increase

the difficulty of one question due to ceiling effect (question was

too easy on baseline). As seen in (Table 2), we are presenting the

aggregate results for the sessions prior to and after this change in

measure for the Memory Loss & Dementia sessions. Completion

of the questionnaires was voluntary and anonymous, and the

publication of these data was approved by the MSK Institutional

Review Board.

Analysis

Analyses were conducted using the statistical program

SPSS 21 (IBM Corp. Released 2017. IBM SPSS Statistics for

Windows, Version 25.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp). Demographic

characteristics, including age, gender, language preference and

birthplace, were analyzed using descriptive statistics (mean,

frequencies and standard deviations). Paired samples t-tests were

used to evaluate change in knowledge on the programs on preand

post-assessments. A p-value less than .05 was considered

statistically significant. Qualitative analyses were conducted

using thematic content analysis, the most frequent themes are

presented on (Table 3).

df: Degrees of Freedom

Sessions conducted before August 2018

Sessions conducted after August 2018: Questionnaire B includes increased difficulty in listed questions

Results

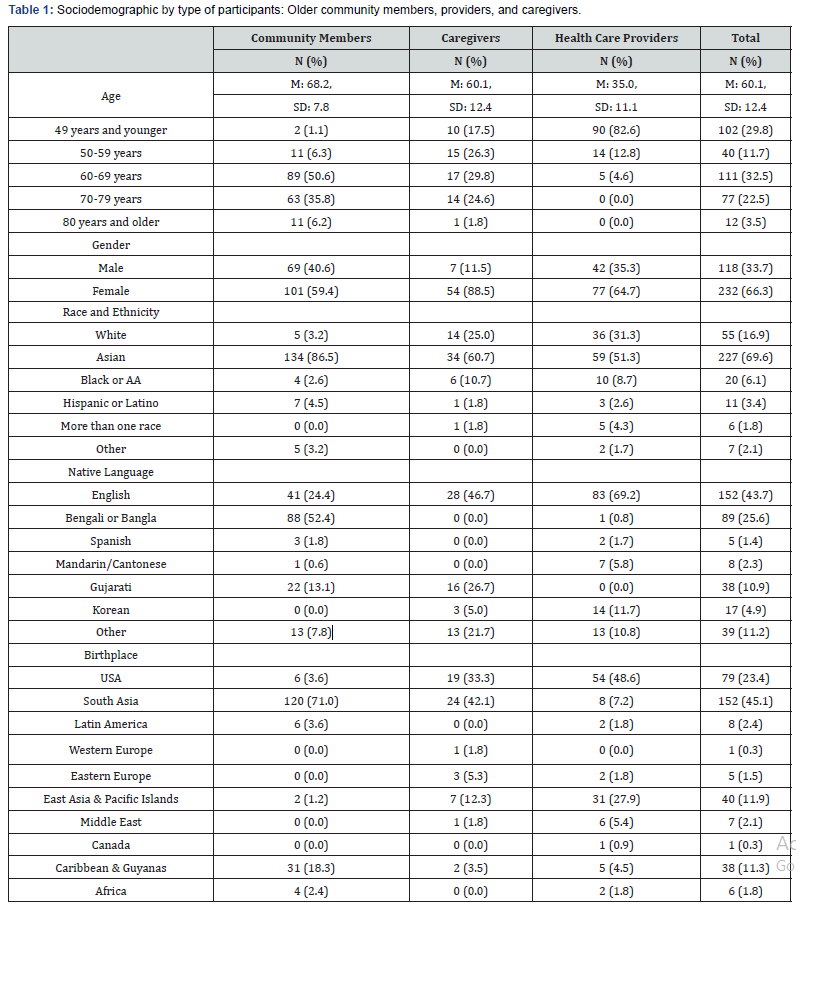

The total sample consisted of 378 participants:182 community

members, 63 caregivers, and 133 HCPs. Sociodemographic data

is presented in (Table 1). Of the older community members

who reported demographic information, the mean age was 68

(SD=7.8) and three out of five were female (59%). The majority

were Asian (87%), half reported their native language to be

Bengali (52%), and 71% were born in a South Asian country

(India, Pakistan, Bangladesh and Nepal). Caregivers had a mean

age of 60 (SD=12.4). The majority were females (89%) and almost

two thirds were Asian (61%). The primary language of 47% of

the caregivers was English, followed by Gujarati (27%). One third

were born in USA (33%) and 42% were born in South Asia.

Note: a Mean and Standard Deviations presented

instead of frequencies; b Other languages include: Arabic, Armenian,

Bahasa, French, German,

Guyanese, Hebrew, Hindi, Kannada, Korean, Nepali, Persian, Poshto,

Punjabi, Romanian, Russian, Tagalog, Tamil, Telugu, Turkish, Urdu,

Vietnamese;

c Other Countries by region include: 1) in South Asia, Bangladesh,

India, Pakistan, Nepal, 2) in Latin America, Brazil, Colombia, Puerto

Rico, Dominican Republic, Paraguay, El Salvador, 3) in Western Europe,

England, Germany, Ireland, 4) in Eastern Europe, Poland, Romania,

Russia,

Botswana, Greece, 5) in East Asia & Pacific Islands, China,

Philippines, Korea, Taiwan, Vietnam, 6) in Middle East, Israel, Syria,

Turkey, Bahrain,

Iran, Saudi Arabia, Lebanon, Iraq, Cyprus, in 7) Caribbean

(non-Hispanic) & Guyanas, Jamaica, Trinidad, Haiti, and 8) in

Africa, Cameroon.

Providers had a mean age of 35 years (SD=11.1), two thirds

were females (65%), almost half (51%) were Asian, the native

language of two thirds (69%) was English followed by Korean

(12%). Most of the providers were born in USA (49%), followed

by East Asian countries (28%). Almost half of the medical

professionals were residents (49%), followed by nurses (24%),

medical students (19%), physicians (5%), patient care technicians

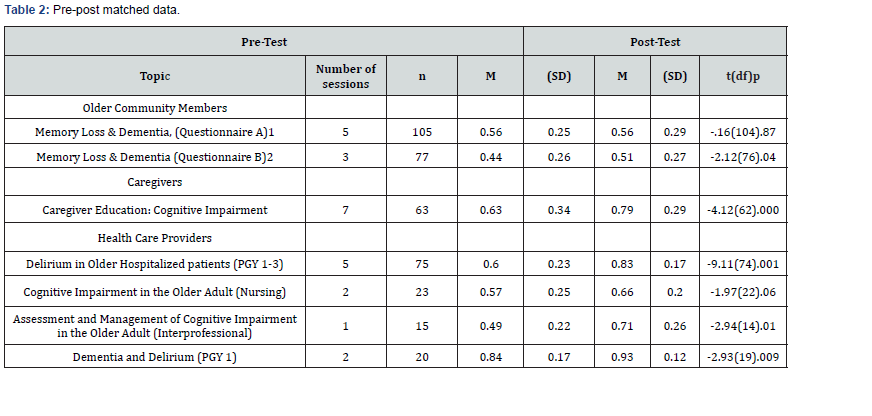

(2%), and social workers (2%). The t-tests for paired samples are presented in (Table 2). The

results indicate a statistically significant difference for the sessions,

Memory Loss & Dementia [t (76) = -2.12, p< .04], conducted with

older community members after the measure assessment was

updated in August 2018. The pre-post evaluations for the sessions

on Memory Loss & Dementia prior to upscaling of difficulty in the

measure conducted between April 2017 to May 2018 did not yield

significant results [t (104) = -0.16 p = .87]. The sessions conducted

with caregivers: Caregiver Education: Cognitive Impairment

showed highly significant increase in knowledge [t (62) = -4.12,

p < .001]. Among the HCP sessions Delirium in Older Hospitalized

Patients (PGY1-3) [t(74) = -9.11, p < .001]; Cognitive Impairment

in the Older Adult (Nursing) [t(14) = -2.94, p = .01]; and Dementia

and Delirium (PGY 1) [t(20) = -2.93, p = .009] showed improvement

in knowledge. There were no significant improvements in

knowledge for the Assessment and Management of Cognitive

Impairment in the Older Adult (Interprofessional) group. All

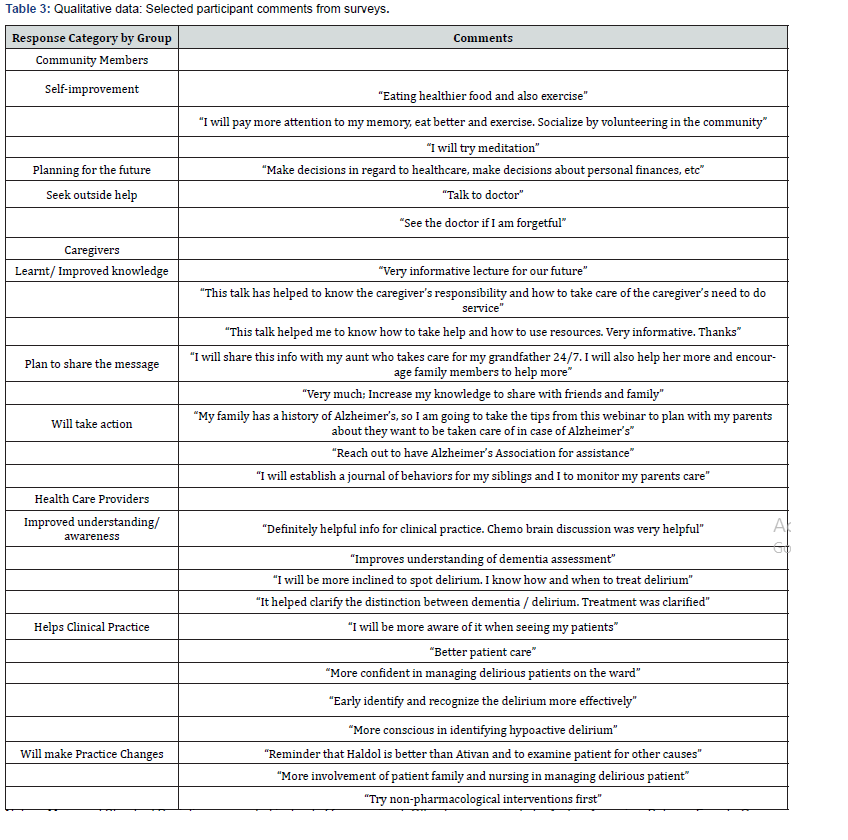

participants were given the opportunity to provide feedback after

completion of the sessions and asked how this information would

change their daily behavior or practice. These responses were

categorized into common broad themes which reflect improved

understanding and plans to make behavioral changes. Selected

themes and comments are presented in (Table 3). Overall, older

adults described specific behavior changes they would make, as

well as resources they would seek out to clarify doubts and obtain

care. Caregivers commented on knowledge gained as well as

future planning for those older family members who might need

dementia care. HCPs reported increased knowledge and detailed

clinical practice changes they planned to make in the care of older

adults with cognitive impairment.

Discussion

Our results demonstrate the successful development

and application of an educational program to improve the

understanding of cognitive syndromes in older minority

communities. We see consistent, significant improvements

in knowledge among older adults, caregivers and HCPs, and

qualitative data that describe improved understanding and

planned changes in behavior after the sessions. We identified

educational needs of older community dwelling ethnic minority

members and their caregivers to provide culturally responsive

educational sessions, in their language in a familiar and

comfortable environment. This specific educational and cultural

tailoring made sessions interactive and open for community

members and caregivers to approach it with a sense of familiarity.

There is a well described national shortage of geriatricians in

the US [21, 22]. Few medical residents choose the extra year of

training required to become a geriatrician, and those going into

other specialties typically get little exposure to the health needs

of older adults during their training. Internists, family medicine

doctors and other HCPs such as nurse practitioners and physician

assistants provide most care for older adults and they should be

trained [21-23] Educational programs like ours help to correct the

deficits in geriatric medicine knowledge in non-geriatrician HCPs.

This is one way of improving the quality of healthcare received by

older patients.

The implementation of this educational approach came

with its own set of challenges. Community health education in

underserved populations is complex: One major barrier we faced

was the wide range in literacy levels of the community member

participants. It ranged from a few people who were illiterate

and could not write their name in their primary language to

people with post-secondary and professional degrees. In many

cases, community organizers and members of the GRIP team

had to sit one-on-one with participants to fill the questionnaires.

Tailoring a pre-post questionnaire to assess knowledge change

in such an audience proved challenging Additionally, we had to

adjust educational materials to ensure understandability. Some

audiences wanted more detailed information and others didnot, so adjustments would often have to be made during the

presentation. These adjustments might have limited the ability to

accurately capture knowledge gain. After analyzing the difficulty

level of the questions based on initial sessions with a wide range

of audiences, we noted consistent high achievement on one item.

We modified that item to increase the difficulty of a question and

subsequent results showed statistical significance in knowledge

improvement. The community members’ qualitative comments

showed a positive impact. In the case of the HCPs, with higher

and more homogeneous educational attainment, the quantitative

analysis showed a significant improvement in knowledge uptake

and it paralleled the qualitative comments.

Another barrier we faced was adapting to the multiple

cultures and primary languages of the community and caregiver

participants. The sessions were interpreted to the most

understood predominant primary language of the audience and the

questionnaires and take-home resources were translated into the

same language. However, it is still probable that the sessions were

not fully understood by all members who attended because some

participants spoke different variations of the primary language or

a different primary language entirely. We conformed to cultural

practices by learning the cultural norms of the community prior to

conducting in each session. The sessions conducted at a mosque

for example had physical partitions between seating areas for

the male and female participants, and our own staff members

respected these boundaries and conformed to the dress codes and

interactions. Transportation and access to the community centers

by participants varied. Even in NYC, where public transportation

is available, it is a challenge for some older community members

and the attendance also depended on the weather. We tried

to schedule sessions according to the best times of day for the

caregiver groups and utilized existing protected meeting times for

HCPs to maintain attendance.

Future directions

We will need ongoing educational efforts and future studies to

assess the long-term benefits of these interventions in increasing

awareness and promoting a more proactive approach to care

from the community members and their caregivers. Patient

reported outcomes could be measured in community clinics after

educational interventions. Behavioral intention measures after

the sessions are also worth exploring. Caregiver related measures

such as stress, satisfaction with medical care, knowledge retention

and change in behavior should be evaluated long-term. Continued

retention of knowledge and the implementation of geriatric

principles by HCPs in their daily practices could also be studied.

Strategies to address challenges around health literacy and

surveys will continue to be addressed and cultural responsiveness

will continue to be integrated into the data collection procedures.

Conclusion

We have successfully developed and applied a critical

educational program about memory loss for older communitymembers, their caregivers and HCPs in diverse underserved areas

of NYC. The education was very well received and prompted the

attendees to propose behavior changes that could potentially

improve the care of individuals with cognitive disfunction. We

demonstrated significant short-term knowledge uptake on

memory loss and cognitive health among the three audiences.

The long-term effect of the knowledge gain and behavior change

needs to be better determined on future studies.

To Know more about Gerontology & Geriatric Medicine

Click here: https://juniperpublishers.com/oajggm/index.php

Click here: https://juniperpublishers.com/oajggm/index.php

To Know more about our Juniper Publishers

Click here: https://juniperpublishers.com/index.php

No comments:

Post a Comment