Pediatrics & Neonatology - Juniper Publishers

Case Report

The aim of this paper is to report an unusual case

of ectopic cervical thymus (CET) in a one-month-old infant and to

underline the importance of considering it in the differential diagnosis

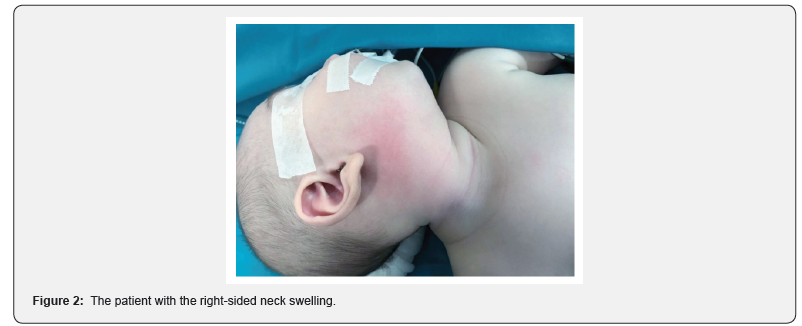

of neck masses in children. A one-month-old male infant was referred to

our Emergency Department for evaluation of a right-sided neck swelling,

which was noted by his parents about 2 days before. The mother’s

pregnancy (medically assisted procreation) was full term and

uncomplicated. The patient had never required admission to the hospital

or surgery. Family history was negative for thyroid disease and

malignancy. On physical examination, his height and weight were normal

in his peers. Vital signs were normal. The cervical mass was soft,

mobile, painless, and 4×3-cm rounded, in the right submandibular region

without a palpable margin. No overlying skin changes, or pits were

evident. No palpable cervical lymph nodes and history of difficulty in

feeding, breathing, and crying were present. Past medical history was

unremarkable and without a history of radiation exposure. His thyroid

gland was not enlarged.

Bio humoral work up included full blood count,

electrolytes, tumour markers (aFP, bHCG, CEA, Ca 19-9), thyroid

function, inflammatory parameters; we did also the immunological exams

(lymphocyte and NK population, Ig G, Ig A, Ig M count, vanilmandelic

acid and T cell receptor excision circles); all values resulted within

range whereas ultrasonography

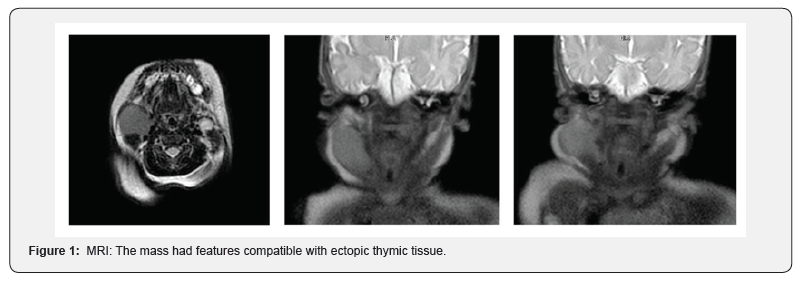

revealed a nonhomogeneous, mainly cystic structure. On magnetic

resonance imaging (MRI) examination (Figure 1), a homogenous mass was

identified. The mass was 4 x 3cm in diameter, slightly hyperintense on

T1-weighted images and was markedly hyperintense on T2-weighted images.

The signal characteristics reflected that of the normal-appearing thymus

gland in the right upper mediastinum. The lesion determined moderate

compression of adjacent structures, particularly the parotid gland

behind. The mass had features compatible with ectopic thymic tissue.

Initially, agree with onco-haematologists and radiologists, we decided

to wait and to follow up the baby clinically and with an ultrasound

after two and four weeks. During the second check, we noticed that the

mass slightly grew up and at the ultrasound the dimensions were

increased. Therefore, after careful preparations, at the age of 3

months, the patient underwent a complete excision of the mass under

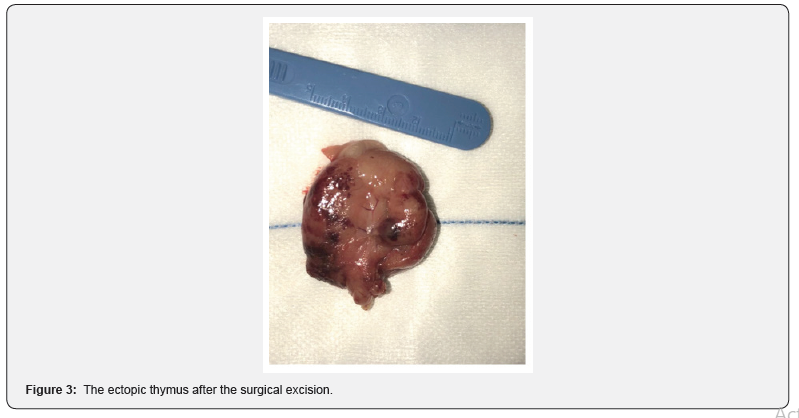

general anesthesia (Figure 2). We used routine cervical approach, and

found the mass was soft, yellow white (Fig. 3), with clear margins and

located in the carotid triangular area, posterior to the

sternocleidomastoid, deeper to it are arteria carotis communis, carotid

artery bifurcation and jugular vein. The postoperative course was

unremarkable, and the wound healed well. The patient was discharged on

the 6th postoperative day. The final histopathological report confirmed

the diagnosis of ectopic thymus.

Brief Discussion

Ectopic thymic tissue may be placed anywhere along the cervical

pathway of the thymopharyngeal duct [1] from the mandible

angle to the manubrium of the sternum. These migrational anomalies

may represent an unusual cause of pediatric neck lump but

it is rarely considered in the differential diagnosis of neck swellings.

To date, the real incidence of CET is still unknown yet; to our

knowledge, there are not more than 130 cases reported till now,

with about 10% occurring in infants [1]; it has unusually been reported

preoperatively in the literature, in fact it is generally identified

incidentally at autopsy or postoperative pathologic examination.

Histologically, an ectopic thymus can either be cystic or solid.

Nowak et al. [2] reviewed 91 cases of CET: 65 cases were cystic

forms, more common than the solid forms (26 cases). They also

reported that CET usually occurs between the ages of 2 and 13

years. In a review of 46 CET cases, 39 (85%) were male, and in 22

(56%) of these, the mass was detected on the right side [3].

The

most frequently presenting symptom is painless swelling. Other

symptoms, such as stridor, dyspnea, and/or dysphagia caused

by compression of the trachea and/or oesophagus, may occur in

10% of cases [4]. The thymus is a specialized organ in the immune

system: its functions are the “teaching” of T-lymphocytes and the

production and excretion of thymosin’s and hormones [5]. In patients

with a CET, only half or less of the organ can be present in

the chest, particularly on the side of the mass: presurgical recognising

of existence of normal mediastinal thymus is imperative to

avoid over-investigation, or biopsy/surgery with unintended total

thymectomy, and subsequent immunodeficiency, specifically in

infants and children. The clear preoperative diagnosis of CET is

difficult and hardly made preoperatively. In almost all reviewed

children, definitive diagnosis has relied on histopathologic examination

after surgery [5]. CET is usually misdiagnosed as cystic

hygroma, cystic teratoma, lymphoproliferative disorders, reactive

adenopathy, and vascular tumours [1]. MRI can help as in the diagnosis

of CET, determining if the mass’s density is similar to that

of normal thymus, as to demonstrate the presence of a mediastinal

thymus. Fine-needle biopsy combined with flow cytometry

analysis have been used in the pediatric population [1,6]. But the

sensitivity and specificity for fine-needle biopsy of thymic tissue

are not known in the children.

The natural history of the CET is unknown. Nearly all cases

reported in the literature have been surgically removed. Schloegel

and Gottschall [7] proposed a clinical algorithm for the management

of CET and suggested that “wait and watch” is the ideal

choice for these patients. But due to the lack of reports demonstrating

that CET would atrophy after puberty, we consider that

pathological examination at the moment is still the definite method

of diagnosis. In view of this, we advise that excision is a good

option for CET, not only to obtain pathology specimens but also to

correct facial asymmetry and avoid clinical symptoms. The best

age above which safe removal of the thymus can be performed has

not been determined. Accordingly, an accurate evaluation of thepresence of the normal mediastinal thymus should be undertaken

prior to removal of an ectopic cervical thymus, especially in children

younger than one year of age, to prevent the risk of immunocompromised

[8-10]. For our patient, we chose to conduct the

total excision of the lesion based on what previously declared, but

also because of the growth speed of the mass, which was rather

rapid. Moreover, in our department, this kind of neck tumour was

usually resected, and other conservative management methods

were not generally practiced. To conclude, ectopic cervical location

of the thymus is a very rarely diagnosed developmental disorder

in children. Our case highlights the role of histopathology

to confirm the correct diagnosis, the importance of investigating

the mediastinal thymus and immunology status before surgery.

Although difficult to differentiate from other conditions, it is important

for clinicians to be aware of its rarity and it has to be considered

in the differential diagnosis of unilateral solid–cystic neck

mass in pediatric age.r fine-needle biopsy of thymic tissue

are not known in the children.

Learning Points

1. Ectopic cervical thymus must be considered in the differential

diagnosis of unilateral neck masses in children.

2. Before surgery, it is mandatory to scan the presence of a

mediastinal thymus to avoid a total thymectomy; the best radiological

exam to demonstrate it is the MRI.Consider, before surgery, to make all immunology tests.

3. Consider, before surgery, to make all immunology tests.

To Know more about Pediatrics & Neonatology

Click here: https://juniperpublishers.com/ajpn/index.php

To Know more about our Juniper Publishers

Click here: https://juniperpublishers.com/index.php

No comments:

Post a Comment