Global Journal of Archaeology & Anthropology

Introduction

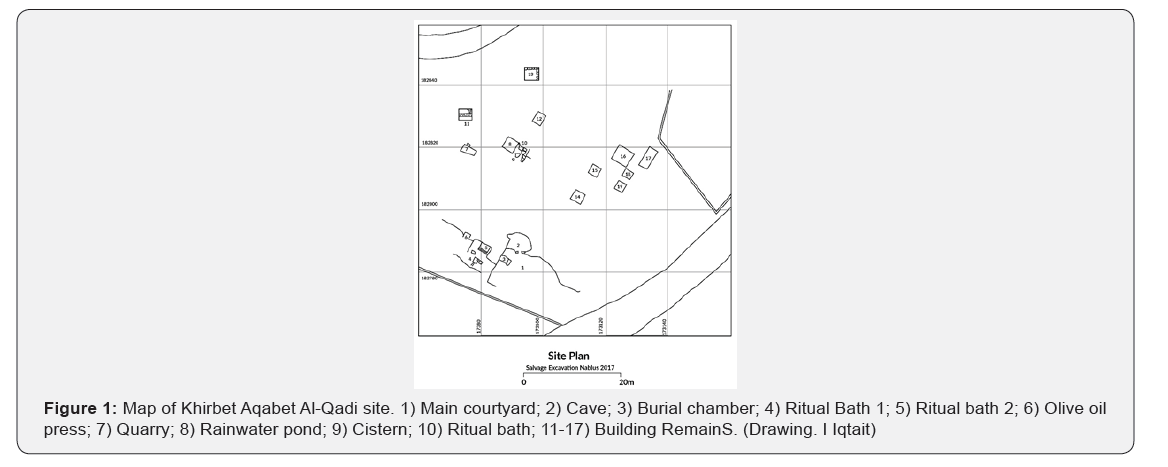

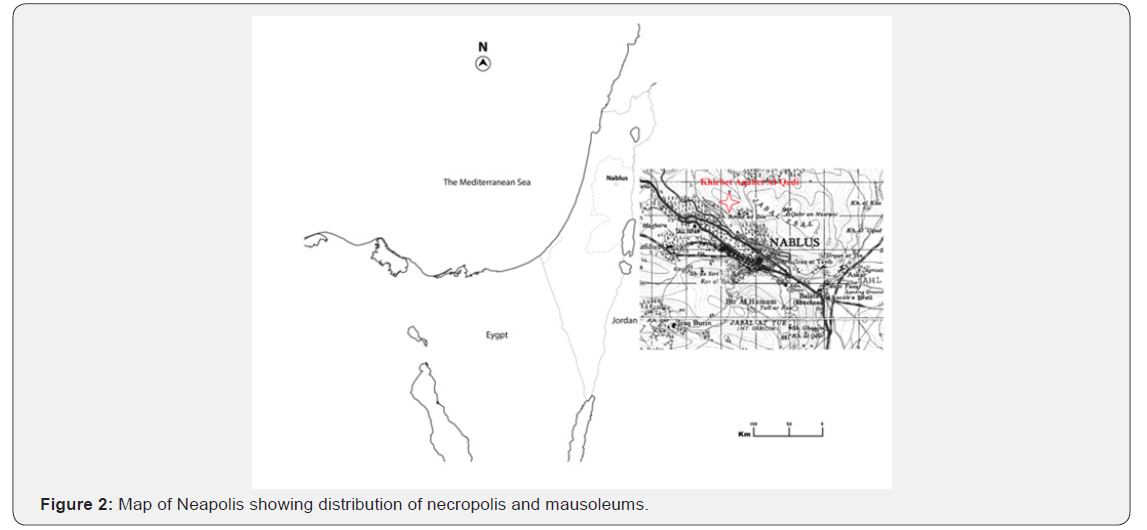

The site at Khirbet Aqabat Al Qadi, where a burial chamber has come to light, is located two kilometres from the city centre of Nablus on the north-western slope of Mount Ebal. At 600 metres above sea level and overlooking the city, it is at latitude 32 °14’19. 53” N and longitude 35°14’37.10” E. The Burial chamber is on the same side of the city as the previously discovered Eastern and Western mausoleums, one kilometre north of the Western and three to four kilometres north-west of the Eastern (Figures 1&2). The Department of Tourism and Archaeology at An-Najah National University is under an agreement with the Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities to explore the site and document the resulting finds. The fact that there were significant archaeological remains on the site was first discovered in 2016 when the owner of the land was clearing the site to build a house. At that time, a brief salvage operation was carried out showing the importance of the site for archaeological exploration.

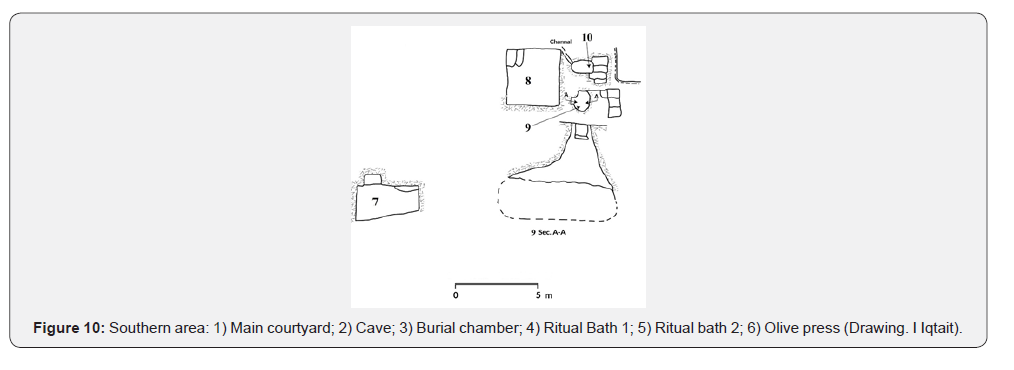

We have found to date a large courtyard leading to an underground burial chamber in which we discovered four sarcophagi containing human skeletal remains, as well as five loculi or niche graves hewn in rock. Another cave showing evidence of inhabitation, containing many artefacts, was also entered from the courtyard, and we found an olive oil press inside another cave west of the courtyard and not far from that, two ritual baths. Further north a third ritual bath was found and a rainwater pond that supplied water to the bath, and to a water storage cistern via an underground channel. In addition, we found a quarry and a building remains on the site.

Aims and Methodology

We aimed to describe the architecture and archaeological remains at the site and carry out an overall survey, documenting our results and creating a site map Figures 1 and 3 (1-10). We compared the sarcophagi found with other examples in the Nablus area to give them historical and archaeological context.

Historical context

Necropolises and burial chambers can be found dispersed across outlying areas of Nablus. The most significant include our burial chamber at Aqabat Al Qady and the Eastern and Western mausoleums found at the entrances to the city [1]. Mausoleums were built along the most important trade routes in the area, eastward toward the Jordan Valley, westward toward the Mediterranean, and northward toward Sebastia in ancient Samaria [1]. In recent years several articles have been published on the Askar Mausoleum (the Eastern Mausoleum of Nablus). The most notable among these is that by Damati [2]. Roman sarcophagi were made of several materials, including wood, lead and stone - the most valuable were of marble and the least valuable of limestone. Stone sarcophagi were highly valued due to their extensive decoration. Less plain stone sarcophagi survived did as they were not valued in later periods and made reusable building material [3]. The Askar Mausoleum and funerary complex, considered the most important in Nablus, is found on Mount Ebal. Roman tombs evolved in Neapolis in two phases. The first phase, from the first century BC to the first century AD, related to the use of loculi, and the second, sarcophagi. The sarcophagi would be placed in the burial chamber along with the existing tombs. This practice occurred until the beginning of the second century AD [4].

Charles Clermont-Ganneau [5] was first to publish a reference to sarcophagi in the region when he mentioned a small lid at Škem. Later, Louis-Hughes Vincent [6] was first to describe fragments from sarcophagi on the slopes of Mount Ebal in 1919. He thought they were like sarcophagi in Jerusalem. He described the walls as fine, the frame as distinctive and the decoration as friezes; he suggested the sarcophagi belonged to the Jewish community or perhaps the Samaritan, dating them to the early first century AD. Abel [7] attributes the mausoleum to the Jewish-Samaritan population, at the time of Hadrian and Marcus Aurelius (134-50 AD). However, Avi-Yohah [8] suggests the sarcophagi belonged to the Samaritan community. According to Smith [9], either the sarcophagi date to between the late first century BC and the early second century or the Crusader period. Damati [10] suggests the Mausoleum belonged to a Samaritan family living in Askar in the late second to early third centuries AD; support for this lies in the fact that two sarcophagi are inscribed with names. Barkay [11] dates the sarcophagi to the late second to third centuries AD when the Samaritan community prospered and spread after the Bar Khoba revolt. Of seven coins found alongside the Samaritan sarcophagi, three date to the Severan dynasty. Another three belonged to the second half of the fourth century. Magen [12], suggested the sarcophagi thought to be Samaritan would have imitated the Jewish sarcophagi from the second Jerusalem period. This imitation was a common practice in Nablus among the Samaritan and pagan populations [4].

In the western Nablus region, sarcophagi were used during the Roman period - they were found at Škem in Sebastia and at other place, in tombs carved into rock, with the lengthwise front panel decorated with relief ornamental friezes on columns. Magen [4] considers they were in imitation of tombs in Jerusalem. The dating and whether Jewish or Samaritan is unclear, but he believes the Samaritans did not develop a distinctive model and the sarcophagi date to the early second century AD [4]. The finding of materials from later periods in some tombs reinforces the fact that caves continued to be used for burial until the early Arab period [4]. Al-Fanni [13,14], suggests the Mausoleum dates to the second century AD. He refers to the finding of a large quantity of bones and black Greek painted pottery at the site, suggesting re-use of the sarcophagi.

This could be possible when considering the intensive building activity in Nablus at that time, the sarcophagi cannot be dated to the time of Hadrian and his successors as Able [7] believes. Those buried may have been Samaritan, Jewish, or even pagan, but, without evidence for exact dating, we cannot make any conclusive assertion. The debate about whether the sarcophagi are Jewish, or Samaritan may be part of a conflict that has a role in controlling the history of Palestine, for political, religious, geostrategic and economic reasons, but mainly due to the well-organized Zionist movement. More accurate dating, bearing in mind the scarcity of archaeological information would need to come from future regional studies of the different workshops and import systems in place in ancient Palestine. Regarding similarities in design and decoration between sarcophagi, a local workshop is indicated, operational during a relatively short period of time.

Burial Chamber, Sarcophagi and Other Structures

Main courtyard

The courtyard measures 18 × 10m and provides entry on the west to the burial chamber and on the north-west to another cave. The courtyard floor has not been excavated, but it appears to be embedded rock in some parts and paved flagstones in others (Figures 3: 5).

Cave

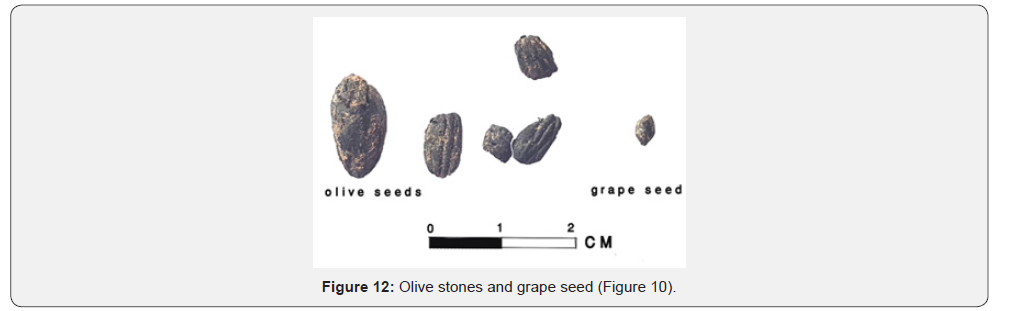

The cave, entered from the north-west boundary of the main courtyard, measures 6 4.5 ×m (Figures 1, 3-4). A large quantity of debris and earth was found inside, and it contained pottery shards from jars, cookware and tableware, several oil lamps and glass bottles and fragments from basalt grinding stones. A fragment of the base of a small jar contained soil, five carbonized olive stones and a grape seed (Figures 12).

Burial Chamber

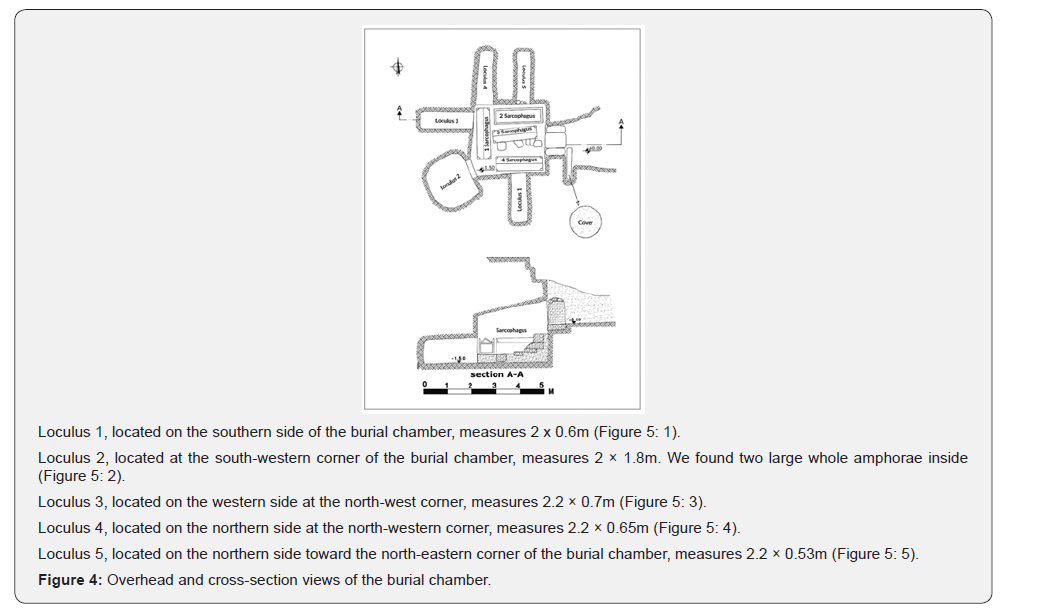

The burial chamber measures 3 × 2.7m and was hewn into limestone. The limestone entrance block could be moved back and forth and was removable. Five niche tombs carved in rock extend outward from the main chamber where four soft limestone sarcophagi were found. They were from Mount Ebal (Figures 1; 3-4; 9).

Sarcophagi

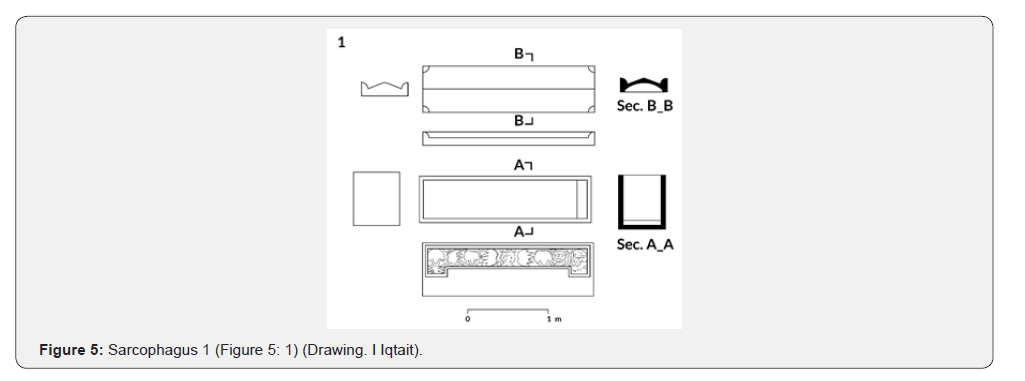

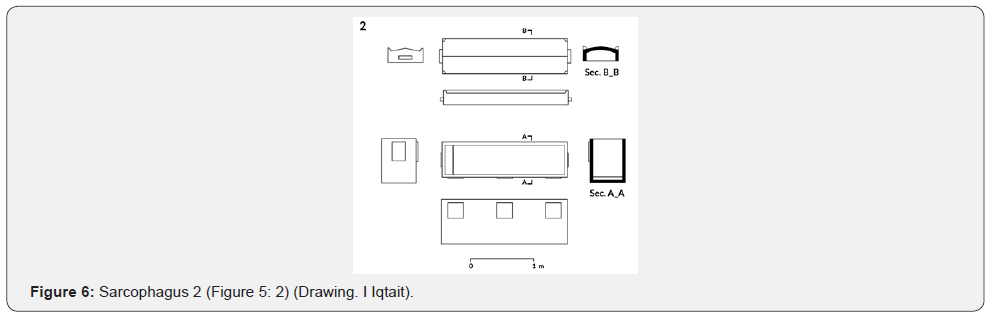

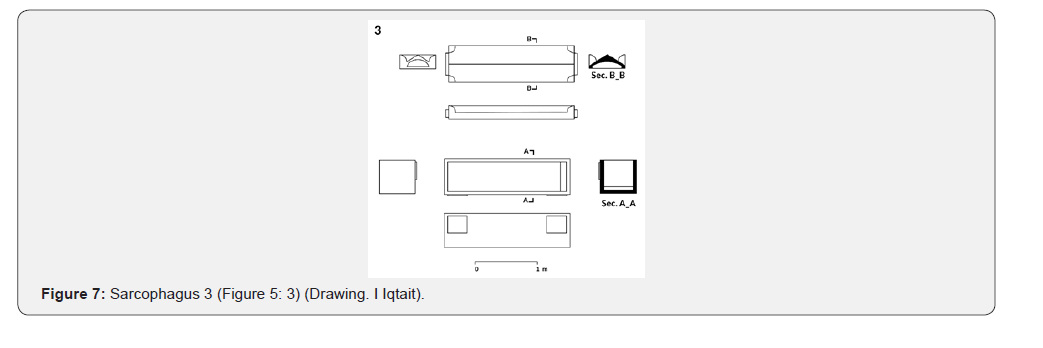

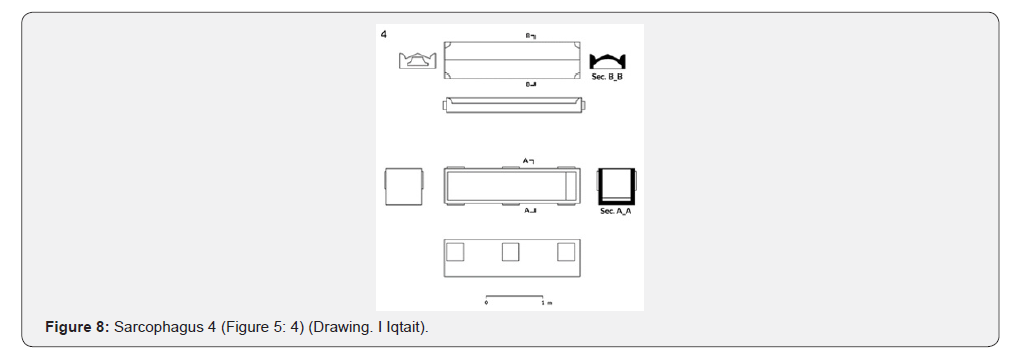

Sarcophagus 1 (Figure 5), located on the western side of the burial chamber, lies north south. There are eight carved vine leaf motifs on the front panel with a vessel in the centre signifying plenty. The sarcophagus is 2.07m long, 0.56m wide, 0.67m deep (Figures: 5-8). Sarcophagus 2 (Figure 6), located on the northern side of the burial chamber, lies east-west. The decoration consists of three geometric squares on the front panel and one on each end panels. It is 2.01m long, 0.58m wide, 0.71m deep (Figures 5: 1, 6 & 7). Sarcophagus 3 (Figure 7), located in a central position in the chamber, lies east-west (Figure 7). The decoration consists of two geometrical squares on either side of the front panel. It is 1.82m long, 0.51m wide, and 0.48m deep. Sarcophagus 4 (Figure 8) is located on the southern side of the chamber and lies east-west. Both longitudinal panels are decorated with three geometric squares. It is 2.01m long, 0.58m wide and 0.71m deep.

Ritual baths

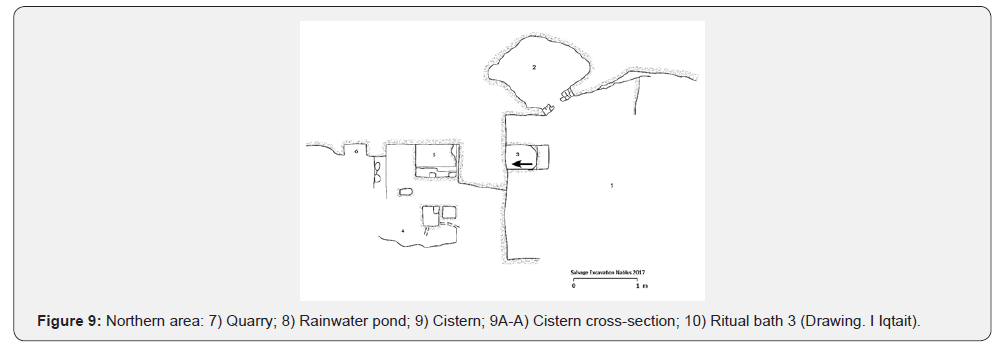

Three ritual baths used for purification before entering a temple, were found at the site. However, a temple has not been found (Figures 1:4; 3: 4; 9). Ritual Bath 1 measures 1.5 × 1m and is located west of the burial chamber and south of Ritual Bath 2. Ritual Bath 2 located west of the burial chamber and north of Ritual Bath 1 measures 3 × 2m. Ritual Bath 3, also found in the northern part of the site, one metre from the cistern measures 2 x 1 x 2m and steps lead down to the base. It would have had a lid, but this was not found (Figures 3: 10 & 10).

Olive Press in Cave

Remains of an olive press were found in a large cave west of the burial chamber. Although the cave contained a quantity of debris, We couldn’t enter to the cave to describe and to do all the documentation of the olive press stone. (Figures 2: 6, 3: 6 and 4: 6).

Quarry

The quarry was found in the north-west of the site. We can see the cut marks on the rock of the limestone. The cut stone surface measures 4 × 2m (Figures 1: 7; 3: 7).

Rainwater Pond

The square pond for collecting rainwater, hewn into limestone, measures 3 × 3m and is 0.5m deep. The water from the pond passed through a cleansing filter created in the rock and then along an underground stone channel to the cistern (Figures 1: 8; 3: 8).

Cistern

The rectangular cistern, measuring 2 x 1 x 2m and located in the north of the site near the rainwater pond, was used to store water channelled from the rainwater pond (Figures 1:9; 3:9; 9).

Building Remains

Building remains appeared at nine different locations during salvage excavations- three in the north and six in the east. We have not determined their exact nature, as funding issues prevented further examination (Figure 1: 11-17).

Artefacts

Amphorae

Three amphorae were found in the burial chamber; two in the western corner were whole, and the third was broken. They share long, conical bodies curving inward at long, narrow cylindrical necks. The entire body and neck are horizontally ribbed. They have long handles on either side. A very small hole is found in the centre of each neck; these holes, made after manufacture, suggest adaptation: they were probably originally produced for wine, but later used for vinegar with holes to prevent fermentation. We found five olive stones and a grape seed in the broken base of Jar 1. Their stoppers would have been of stone or mud. One carved hard white limestone stopper was found nearby. Some scholars suggest this stopper type was used from the mid-fifth to mid-sixth centuries AD (Figure 11: 1-3).

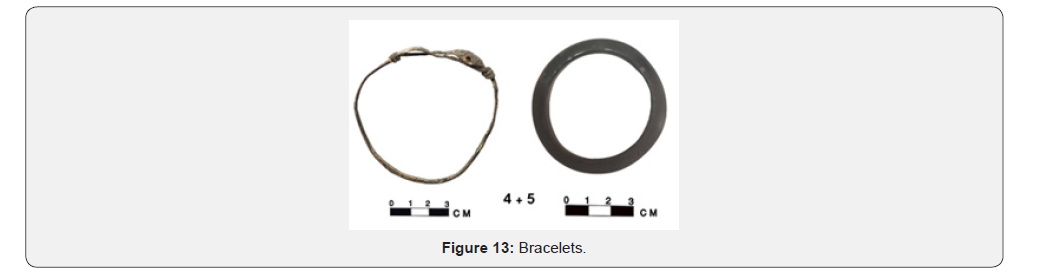

Bracelets

Two bracelets were found in the burial chamber: one metal with an ornamental snake design and the other plain blue glass (Figure 13).

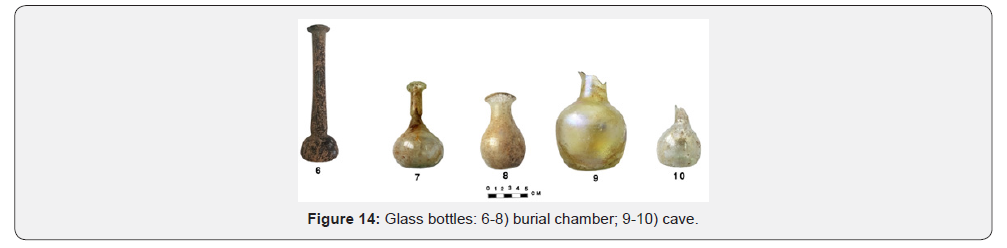

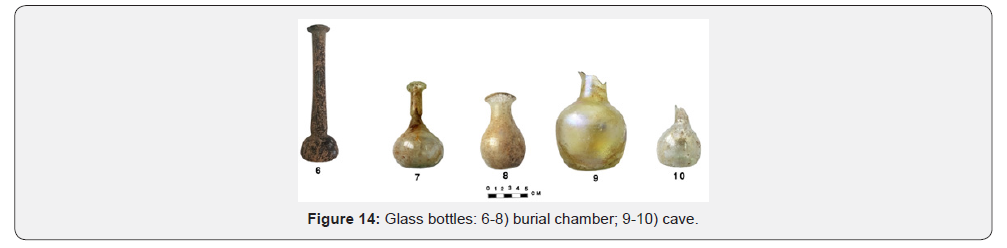

Glass Bottles

Five glass bottles of different shapes and colours were found: three in the burial chamber and two in the cave (Figure 14: 1-5).

Funerary Marker

A carved hard limestone funerary marker was found outside the burial chamber: an upper pyramid sits on a cylindrical base. Symbolizing the soul of the deceased, pyramids were also found on funerary markers in Jericho [15,16] (Figures 15).

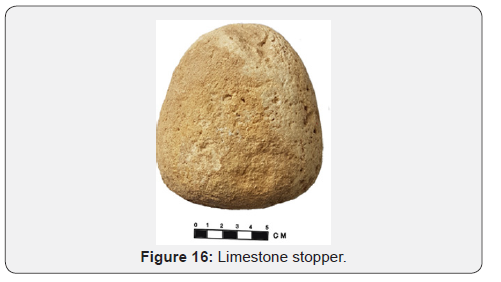

Stone Stopper

A rounded conical hard limestone stopper was found in the burial chamber (Figure 16).

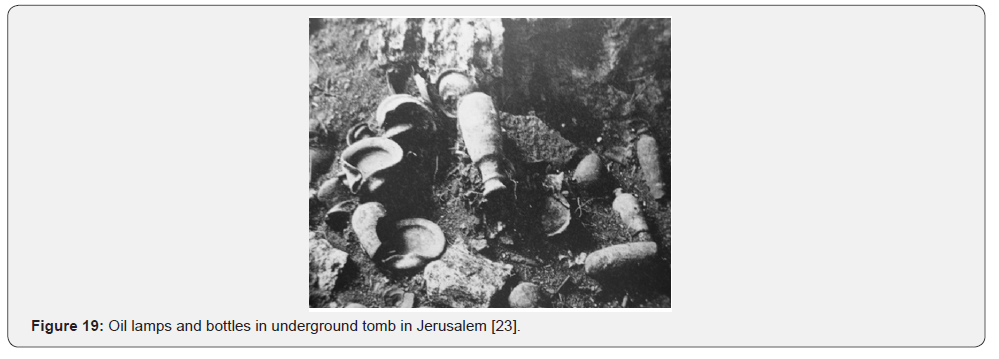

Oil Lamps

Twenty-three Samaritan type oil lamps were found, made with moulds - except one of carved white limestone. Two were from the burial chamber, sixteen from the cave and five on open ground. Samaritans, Christians and Pagans in Palestine and Jordan used Samaritan lamps from the late Roman to the early Islamic periods [17]. Examples were found in Nablus and Apollonia-Arsuf [18,19]. We identified four types: A-D

a. Type A: rounded body, a wide short nozzle and concave sides; with ladder, geometric and floral motifs, they usually have a star-shaped handle and a double ring base. They date to the late third to fifth centuries AD [17].

b. Type B: a more elongated body than Type A, a long narrow nozzle and a groove between the filling hole and the wick. Geometric circles, semi-circles, triangles, ladders, lines and dots - as well as palm branch motif form the decoration. They have different-shaped handles, knobs and tongueshaped and ring bases [17].

c. Type C: similar to Islamic lamps with an elongated body, a nozzle a groove and large filling hole; decorated with palm branches, dots, lines, seven-branch candlesticks and geometric designs they date to the sixth-seventh centuries AD [17] .

d. Type D: carved from smooth white limestone: ovalshaped, tapering toward one end,

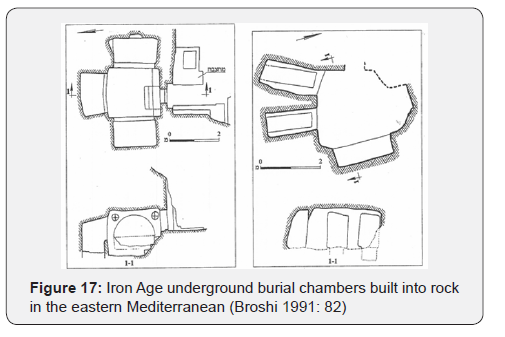

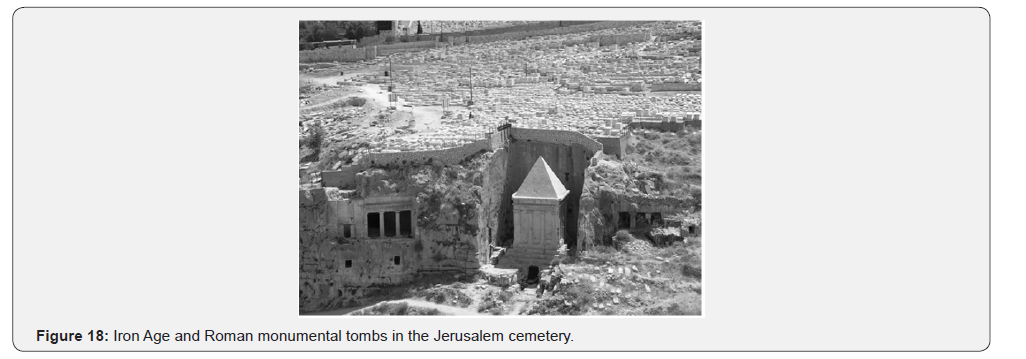

Eastern Mediterranean Tradition: Constructing underground Funerary Caves

The building of burial chambers and artificial caves for different purposes began in Neolithic times in Palestine, when the architectural model was created such as Tell El-Sultan. Semihabitational forms appeared during the Iron Age, and later, Hellenistic and classical cultures influenced design and rituals. During the Bronze Age, Neolithic architecture declined, and the number of caves used as dwellings decreased [20]. However, Iron Age underground construction became more generalised with large underground storage and water supply systems. An example is the 700m of tunnelling under the old Jesusalem [21]. Funerary construction of artificial caves became widespread and their functional use continued until the beginning of Christianity, shown in the Sacred Sepulchre in Jerusalem [22].

In this period most of the remains in the artificial burial caves belong to the same family. The remains of libations, ritual fires and food and drink offerings are also found with the human remains [23,24]. In general, from the seventh-sixth centuries BC we see large burial chambers of wealthy families excavated in rock. A staircase led down from the square metre entrance to a chamber with niches radiating outward [23]. In the fifth century, we see Hellenistic influences and in the beginning of the third century, the accumulation of human remains led to using ossuaries and there is an increase in finds of household items that would continue through most of the Roman era. Numerous caves find, now believed to have been for funerary rituals rather than inhabitation, result from the Roman war in Palestina [25,26].

During the first century AD with the advent of Christianity, the use of ancient burial chambers as community meeting places for rituals increased [27,28]. In the Byzantine era (fourth - fifth centuries AD), major underground projects, as in the case of caves at Tefen, show complex constructions for family use [29-35]. The entrance design was anti-looting and the tombs extended outward from a central space [36-40].

Conclusion

Khirbet Aqabet Al-Qadi is an important Samaritan site in the Nablus area. Two caves showing evidence of residential use, structural remains and many artefacts were found. Functional elements included an olive press, a rainwater system, ritual baths, and a burial chamber. The olive press, large amphorae, and olive stones and a grape seed, indicate a rural settlement with an agricultural economy based on olive cultivation for cooking and lighting oil and viticulture for wine and vinegar. The four sarcophagi in the burial chamber and numerous artefacts provided information to conclude that the hamlet was inhabited from the Roman period (63 BC-324 AD) to the Byzantine Period (324 AD-16 Hijra/638 AD). The depiction of a vase and grapevine leaves on Sarcophagus 1, and nearby amphorae signify large scale production and export of wine.

To Know More About Global Journal of Archaeology & Anthropology Please click on:

No comments:

Post a Comment