Open Access Journal of Surgery Juniper Publishers

Introduction

The relationship between H. pylori infection and gastric cancer has been acknowledged for almost 20 years [1]. Some studies have demonstrated that H. pylori eradication reduces the incidence of gastric cancer [2], and consequently the health insurance system in Japan has approved eradication therapy for patients with H. pylori gastritis. However, even after successful H. pylori eradication therapy, some patients still develop gastric cancer. Furthermore, the endoscopic appearance of gastric cancer after eradication therapy is reported to resemble gastritis, making it difficult to diagnose the extent of the cancer [3-5]. Saka et al. [5] have clarified the characteristic endoscopic features and histological characteristics of gastric cancer after eradication therapy, thus facilitating more accurate diagnosis. Nawata et al. [6] have reported the characteristic endoscopic features of the stomach that tend to be predictive of gastric cancer development after eradication.

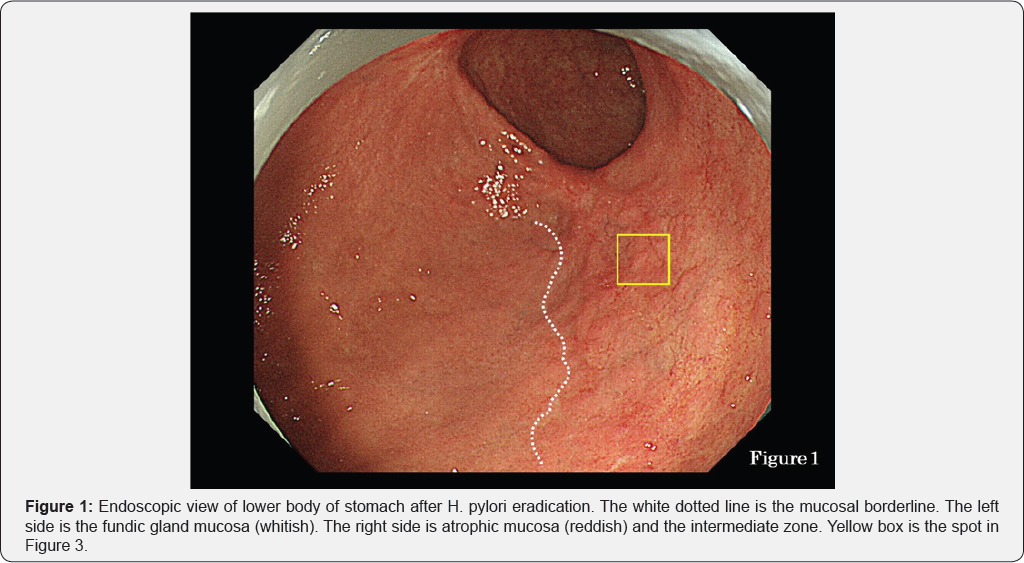

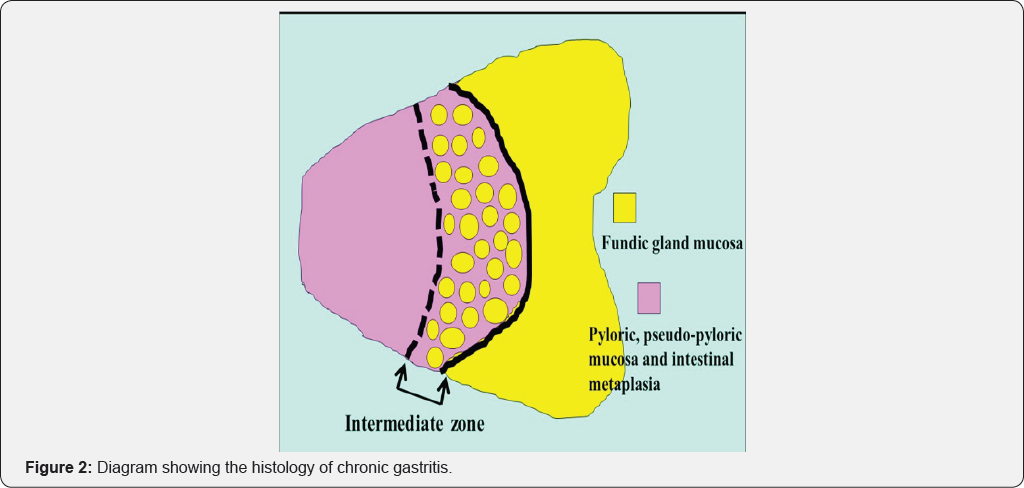

This has been termed the "reversal phenomenon" on the mucosal borderline [6]. In chronic active gastritis due to H. pylori, inflammation activity is more marked in the fundic gland mucosa than in atrophic mucosa including intestinal metaplasia. Therefore, in chronic active gastritis, the fundic gland mucosa appears reddish and atrophic mucosa appears whitish [7]. After eradication, inflammation activity disappears from the fundic gland mucosa and its color changes from reddish to whitish. This means that the color of the atrophic mucosa has a relatively reddish hue when observed by endoscopy. This color change corresponds to the "reversal phenomenon" (Figure 1). In the atrophic mucosa, a whitish elevated area is evident within the reddish part (Figure 1). This area is termed the intermediate zone [8,9]. In chronic gastritis, the intermediate zone is the area in which fundic glands, pseudo-pyloric glands and intestinal metaplasia coexist, representing the border between adjacent atrophic mucosa and fundic gland mucosa (Figure 2). Endoscopically, the whitish elevated part in the intermediate zone is fundic gland mucosa and the reddish part is intestinal metaplasia (Figure 1).

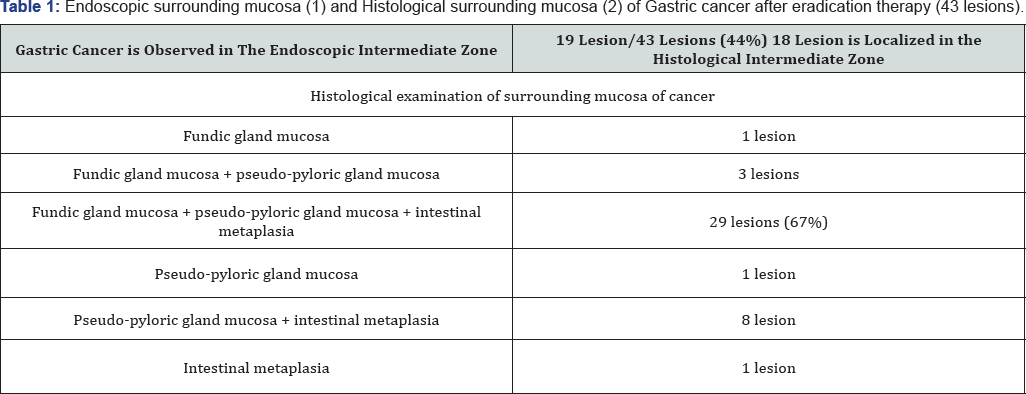

Using endoscopy, we studied 43 lesions of gastric cancer after eradication therapy and found that 19 of them were located in the intermediate zone (Table 1). Furthermore, histological examination revealed that 29 lesions were located in the intermediate zone (Table 1). Figure 1 shows a case of gastric cancer after eradication therapy. The yellow box in the figure shows a lesion suspected to be cancerous because of its slightly whitish hue. This suspected cancerous lesion was located in the intermediate zone containing a mixture of whitish elevated areas and reddish areas. NBI (narrow-band imaging) endoscopy at lower magnification revealed an unclear white zone [10] pattern and an irregular vascular pattern, suggestive of cancer (Figure 3, white arrows).

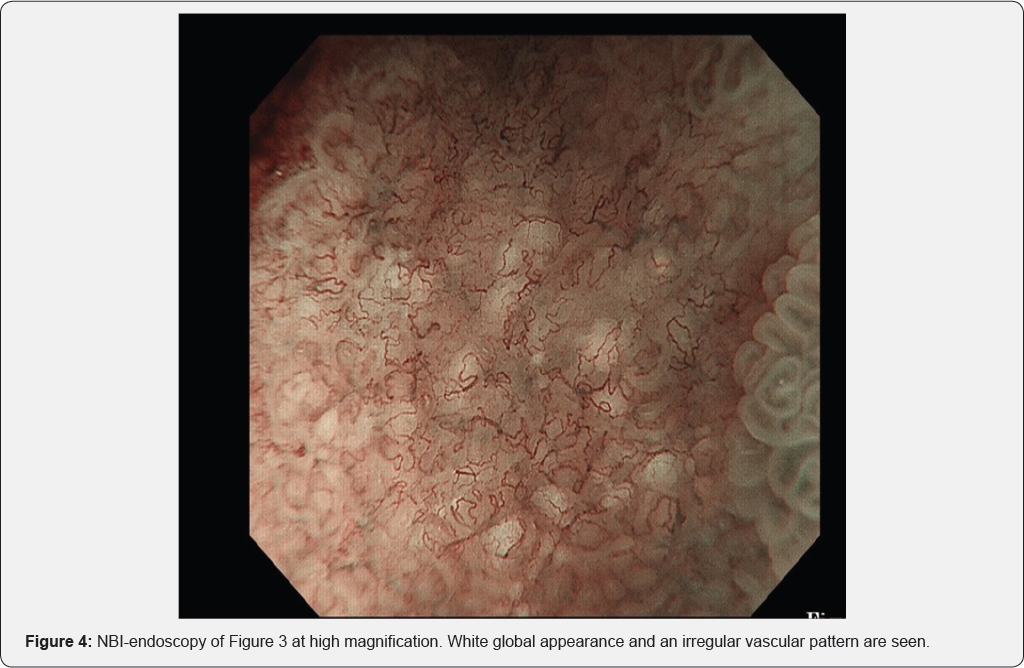

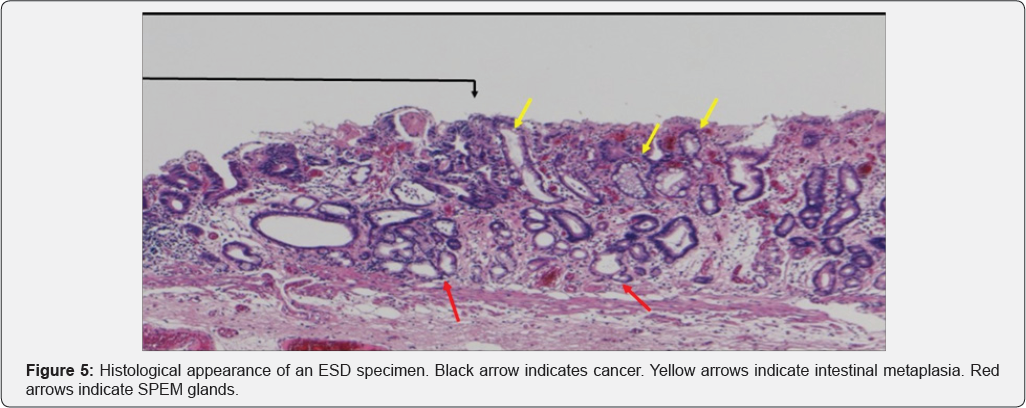

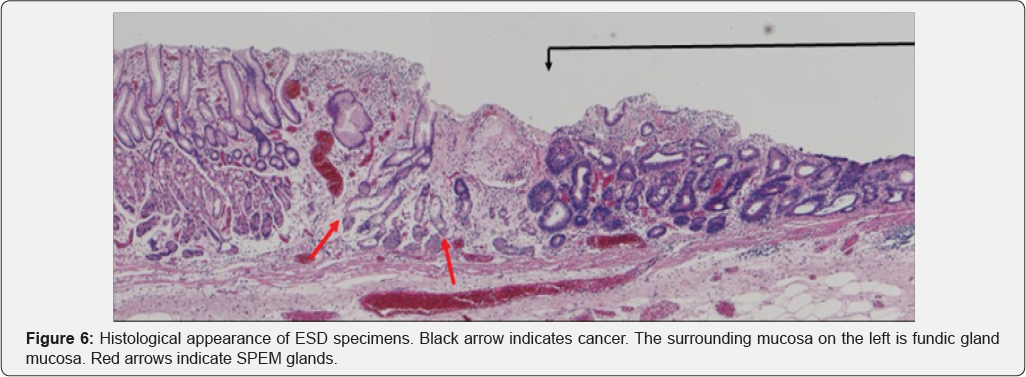

In Figure 3, area A shows round pits indicating fundic gland mucosa and area B shows a tubular pattern indicating atrophic mucosa or intestinal metaplasia [11,12], thus corresponding to the intermediate zone. NBI-endoscopy at high magnification demonstrated a white global appearance [13] with an irregular vascular pattern (Figure 4). A biopsy specimen was diagnosed as differentiated adenocarcinoma, and endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) was performed. The ESD specimen showed mucosal differentiated adenocarcinoma (Figure 5 & 6 black arrows). In addition, intestinal metaplasia (Figure 5 yellow arrows) and fundic glands (Figure 6) were seen in the surrounding mucosa, thus corresponding to the intermediate zone.

Many articles have suggested that development of gastric cancer is related to intestinal metaplasia [14,15] and that gastric cancer occurring after H. pylori eradication therapy also has a relationship with intestinal metaplasia [16]. However, we recognized that gastric cancer after eradication therapy developed more frequently in the intermediate zone than in areas of intestinal metaplasia. No previous reports have suggested that fundic glands and pseudo-pyloric glands are related to the development of gastric cancer. Our results suggest that the process of metaplasia from fundic glands to pseudo- pyloric glands and intestinal metaplasia may be related to development of gastric cancer. This process is evident in the case of spasmolytic polypeptide-expressing metaplasia (SPEM) [17-19].

In SPEM, loss of parietal cells disrupts the proper differentiation of other lineages such as chief cells [18,20], and metaplasia from chief cells to mucus cells forming glands with dilatation occurs [17-19]. These glands are similar to Brunner glands or antral pyloric glands [17-19]. This process of SPEM occurs as a result of inflammation due to H. pylori [17-19] or administration of drugs [21]. These mucus cell glands are referred to as SPEM glands [17-19], and correspond to pseudo- pyloric glands pathologically. Furthermore, goblet cells appear in SPEM glands, marking the onset of intestinal metaplasia [19]. Yoshizawa et al. [19] have reported that H. pylori infected Mongolian gerbils developed SPEM initially in the intermediate zone along the lesser curvature, and that this subsequently spread out towards the greater curvature, goblet cell intestinal metaplasia developing only at a late stage of infection. They concluded that SPEM develops early in H. pylori infection in this model, and that alterations in gland morphology arise from SPEM glands during the course of gastric infection, goblet cell intestinal metaplasia developing subsequent to SPEM [19]. We recognized that the histological findings described by Yoshizawa et al. correspond to the histological features in the surrounding mucosa of the gastric cancers we observed after eradication therapy. SPEM glands are evident in Figures 5 & 6 (red arrows). Goldenring et al. have also stated that gastric cancer develops from SPEM glands, and not from intestinal metaplasia [17,18].

SPEM is thought to be most active in the intermediate zone, and accordingly gastric cancer is thought to develop there. The fact that 29 of 43 (67%) gastric cancer lesions we observed were located in the intermediate zone appears to support this. Therefore it appears that more attention should be paid to alterations in gland morphology from chief cells to SPEM, and subsequently to intestinal metaplasia, to clarify the development of gastric cancer, including analysis of genetic variation. Our present results suggest a paradigm shift when considering the development of gastric cancer.

No comments:

Post a Comment