This study investigated the satisfaction of 303

undergraduate students who enrolled in traditional 200-level

criminology/ criminal justice courses. University students were offered

the opportunity to self–select into one of four blended online ratios

ranging from 10%, 30% 70% to 90% of the course operating within an

online environment. OLS linear regression analysis suggests that

students who selected lower intervals of online blended instruction (or

high intervals of F2F instruction) were statistically more likely to

report higher levels of overall satisfaction in the course.

Alternatively, the findings suggest that higher ratios of student

selected online instruction may lead to higher levels of student

dissatisfaction. OLS data findings reported that younger university

students who require more flexibility and convenience of scheduling, are

enrolled in higher course loads and/or majoring or minoring in the

subject matter produced statistically higher levels of student

satisfaction.

Keywords: Online;

Blended; Hybrid; Face to Face; F2F; Student Satisfaction;

Learner-Content; Learner-Instructor; Learner-Learner;

Learner-Technology; Interaction; Student Satisfaction Survey

In the current COVID19 pandemic environment [1],

post-secondary academic institutions and instructors are scrambling for a

best practices model to continue to teach their students. Additionally,

the university student (or consumer) searches for the instructional

delivery that suits their needs and priorities. With the increasing cost

of living, expectation of employment, travel, tuition and textbooks,

students are consciously re-assessing the value for their dollar to

determine which institution is right for them. We know when universities

offer the availability of online and blended courses [2] as well as

flexibility in scheduling [3,4] students prefer and are likely more

satisfied with their courses [4]. Blended learning offers a solution to

traditional face to face lecture contact, combining technology with

interval levels of face to face instruction.

It certainly appears that undergraduate students as

consumers of educational attainment want more choice and selection of

course instruction, not less. As consumers of learning, student

satisfaction needs to be accounted for. As Brooks [5] suggests, a

significant majority (83%) of students preferred some form of blended

instruction rather than a traditional face to face (10%) or

traditional online (7%) course. The Center for Applied Research also

reports that prefer digital mediums, that device ownership (tablets,

smartphones, tablets) is greater among students than the public

marketplace and students view their technology as important to their

education and success (2016:5). The use of technology within an online

environment appears to breed a form of success and/or satisfaction not

found within traditional face to face courses. This study explores the

use of interval/ ratio levels of student self-selection of course

delivery to determine if/ and at what ratios of blended course delivery

impacts overall reported student satisfaction.

Student satisfaction can be conceptualized using a

variety of indices from objective performance measurements assessing

grade attainment to subjective measures of student attitudes on process-

based learning and its efficacy [6]. Student satisfaction surveys have

been numerous and rely on similar questions [7]. As a result, many

satisfaction surveys probe the interactions learners have with one

another, their instructor, course content, online technology and the

method by which it is delivered [8]. There is

ample research to suggest that blended learning instruction can

impact student satisfaction. Blended learning generally offers

differing environments that connect traditional lectures with

some form of online learning [10]. A meta-analysis by Moskal

et al. [10] examined the adoption of blended learning to its

implementation and outcomes. The study reported higher levels

of satisfaction among students who enrolled in blended courses

versus fully online or lecture-based modes of instruction [10].

Research suggests that even if there may be no difference within

instructional delivery, students still prefer blended learning.

Owston et al. [11] found similar levels of satisfaction when students

were asked to compare their blended course instructional delivery

to other traditional courses they previously had taken; almost

70% of students reported they would take a blended course again.

This was also confirmed by Madriz and Nocente (2016) who

surveyed nearly 600 undergraduate students finding overall levels

of satisfaction were higher among blended learning and student’s

willingness to take another blended course. Vernadakis et al. [12]

compared blended and face to face (F2F) sections and found that

students enrolled in blended sections reported significantly higher

satisfaction (conceptualized from a twelve-question survey). Forte

and Root (2011) reported similar findings in which students who

enrolled in a blended format had higher levels of satisfaction

versus traditional courses with some levels of web-enhancement.

Melton et al. [13] compared the satisfaction of students enrolled

in four general health courses finding that satisfaction scores were

statistically higher for those students enrolled in three blended

learning courses than one traditional F2F course. Therefore,

there appears to be significant advantages for students when

employing a blended learning method to their course load. A

study conducted by Dziuban et al. [14, 15] reported higher levels

of student satisfaction in a variety of blended courses with 85%

of students agreeing that they were satisfied and 67% reporting

they would like to take another blended course.

Utilizing both

blended and F2F instructional delivery within a nursing student

population, Kumrow (2007) found that blended students were

more satisfied than unsatisfied. These studies have all implied that

there is an importance of learning independently outside of the

classroom which has positive impacts on satisfaction, grades and

future expectations for blended courses [16]. The question may

not be why an instructor may implement blended learning, but

rather why wouldn’t an instructor consider this blending learning

opportunity. Student satisfaction includes inherent factors which

are often difficult to operationalize such as the motivation to taking

a course to a student’s level of pleasure throughout the course to

the effectiveness of the educational experience (Wang, 2003). Wu

et al. (2008) suggest that higher levels of student satisfaction within

a blended learning approach is due to a student’s perceived ease

of use, value of the content and the climate or environment itself

(for involvement and social interaction).

Further research by Wu

and Liu (2013) confirmed that perceived ease of use is positively

correlated with student satisfaction. Sahin and Shelley [17]

suggest, it is not just ease of use but also the value and usefulness of

the content (similar to any traditional F2F or fully online course).

Therefore, each instructor’s inherent design, organization, choice

and ease of software implementation and adoption (or lack

thereof) of content and value within performance measures

can impact student satisfaction. As such, the value of learning

interactions and outcomes can often be associated not just with

student satisfaction but also the choices instructors make when

selecting software and organizing a course. This best reflects what

we know in blended learning. While blended learning appears to

offer significant value and benefits to students, choices instructors

make should ensure that there is an ease and proficiency of use of

software within course delivery is paramount to ensuring student

success and/or satisfaction. Should students not be proficient

in the software and/or frustrated with the layout of the course

design, satisfaction may wane. Therefore, student success and

satisfaction can closely be tied to the design of the blended course.

The design and implementation of blended instruction requires

a thoughtful approach to content, the technology being utilized and

performance measurements [18,19]. Some studies offer quality

assurance checklists to assist instructors (Chauhan et al., 2016)

however, there is no uniform one size fits all strategy. Therefore,

instructors need to ensure that new online learning environments

are designed appropriately for their targeted audience while also

meeting the needs and expectations of students [17]. Due to the

holistic and individualized approach to the adoption, development

and implementation of courses (not just blended), it creates a level

of difficulty and uncertainty in ascertaining what blending works,

with which student populations and whether these courses can

even be compared to traditional F2F or fully online courses. As

meta-analyses of studies have identified, there is a lack of matched

or equivocal groups of students to make often generalizable

comparisons between blended, traditional face to face and

online courses [6,16,20].

As such, there are limitations to simply

suggesting that blended learning, as a one size fits all strategy

will be effective. Satisfaction is often measured conceptually or

operationally differently across studies which can lead to mixed

results. Other studies have proposed that success be measured

in terms of mean/average disparities of grades between groups

of students but perhaps the performance measurements in the

courses were different. Some studies lack more rigorous testing

to examine correlations and/or relationships. As such, there are

limitations in asserting that blended learning is simply better than

traditional face to face or online learning instruction. This is not

simply the fault of poor research methodologies but rather the

lack of being able to randomly select students (for ethical reasons)

and how university and college courses are offered/ distributed

to instructors on an annual basis (leading to logistical issues). The

lack of random sampling and selection, experimental designs and

rigorous testing means that instructors and students should have

a healthy level of skepticism of blended learning.

Meta-analyses

indicate promise in the adoption of blended learning but due to the lack of rigorous methodological approaches, there is no one

perfect strategy on how to employ it [6,16,20]. An instructor’s

selection of design and construction of blended learning within

a course can and should be individualized to fit every instructor

and student’s needs and priorities [22]. Therefore, there is not

likely one specific percentage or interval that can be used to assert

where blended learning is more successful than unsuccessful [23].

There does not appear to be a one size fits all ratio of blended

instruction that will universally be effective [11]. Several studies

and meta-analyses have reported similar findings where students

prefer and/or rank blended course instruction over traditional

face to face instructional delivery [20, 23] despite a lack of

consensus of the appropriate ratios of blending. It should be noted

that comparisons are often made between blended learning and

traditional and/or online courses as if blended ratios were at a fixed

ratio [10].

Despite these limitations, the evidence still supports

the use of blended and online learning environments in that they

can offer higher levels of student satisfaction than traditional face

to face (F2F) instruction [16, 24]. This would suggest that there

may be tipping points (for every instructor) when comparing

success and satisfaction in and out of the classroom. As Shea et

al. (2006) point out, having examined thirty-two colleges, an

instructor’s teaching presence is positively related to a student’s

sense of learning community and direct instructional facilitation.

Therefore, while students may appreciate the convenience of

hybrid/blended/independent time, that friendly face in the

course is also likely a necessity when constructing a course that

will ensure student satisfaction. A 2009 study by Morris and Lim

examined the influence of instructional delivery and student

learning interactions. Their findings suggest that in addition to

age and prior experiences with distance learning opportunities

impact students’ satisfaction; a student’s preference in delivery

format and average study times are increasingly relevant factors

in student satisfaction. This study suggests we need to consider

other circumstantial and/or situational factors that are relevant

to whether student satisfaction is attained - flexibility and

convenience within a student’s life.

A 2016 government report reports that college and university

students are working harder than ever before, where students

are often taking full course loads (considered full time) while also

employed either part or full time. Nearly half of students taking a

full course load (41%) were currently employed either part or full

time (Kena et al., 2016: 221). Of all students reporting, two in ten

(18%) were employed 20-34 hours a week and one in ten students

(7%) were working over 35 hours a week (Kena et al., 2016: 221).

Therefore, flexibility is a significant need for a majority of students

[10,11]. Owston et al. [11] found that students typically benefit

from increased time and spatial flexibility during the delivery of

their courses providing them more resources and autonomy to

regulate their own learning. As Packham et al. [25] suggest, the

causes of student failure in online courses are often attributed

to issues of family, employment and management support.

Therefore, providing more flexibility in time management has a

significant impact on satisfaction [3, 26]. Therefore, generating

an instructional delivery that facilitates choice and selection of

blended learning may allow for higher levels of student success

and/or satisfaction.

There is evidence to suggest that student selection of

instructional format (when students are offered the opportunity

to choose) may have an impact on student satisfaction. A study

by Yatrakis and Simon [27] found that students who chose to

enroll in courses within an online format achieve higher rates

of satisfaction and a perceived retention of information than do

students who enroll in online courses where no choice is provided.

This concurs with the research of Debrourgh (1999) in that selfselection

and satisfaction can be linked to a student’s retention of

information. The findings of Yatrakis and Simon [27] suggest that

students feel a greater degree of satisfaction when allowed to selfselect

for online courses and that choice may carry over into their

perception of retained information. These results can be used to

support choice and self-selection as satisfying the preferences of

the student consumer. This study explores the interval levels of

student chosen instructional delivery on overall reported student

satisfaction. While the majority of research points to selection

being an advantageous option for students, other research [28]

suggest a level of mixed results in whether instructional delivery

has an impact on student satisfaction. Some studies have found no

significant differences between the ratios of blended instructional

delivery and satisfaction [29,30]. As such, this exploratory study

seeks to add to the limited amount of research on student choice

of blended instructional delivery and how other factors (explored

above) impact on student satisfaction.

This exploratory study examined students enrolled in seven

undergraduate courses offered over a sixteen-week semester

cycle. This was a convenient sample of students where no random

selection existed. This is obviously a limitation but one that

allowed student choice and selection of course instruction. Initially,

there were 334 participants registered for the seven 200-level

criminology/ criminal justice courses. Twenty-two students

were removed from the study having dropped or withdrawn

from the course throughout the semester. An additional nine

students were removed from the study for not having completed

survey instruments. Therefore, the sample size for the purpose

of analysis was 303 participants. This study conceptualized and

operationalized four blended delivery systems that students could

select as developed by Twigg [31] and the Sloan Consortium [9]:

(1) replacement (90% F2F:10% online); (2) supplemental (70%

F2F:30% online) and two emporium options (3) 30% F2F:70%

online and (4) 10% F2F:90% online. The most traditional offering

was replacement delivery where 90% of the course would be face

to face (F2F) and 10% within an online environment. As students

considered transitioning away from face to face traditional mlectures, they could connect with one another and the instructor

through the use of discussion boards and additional digital-based

lectures (rather than F2F).

Once a student had selected their

desired blended instructional delivery, they could opt to revise

this offering after the first exam (one month; 8 classes into the

course). This offered each student more flexibility, an operational

component of Twigg’s [31] buffet style approach Students were

asked to complete several pre-test and post-test surveys which

included Elaine Strachota’s Student Satisfaction Survey (2006)

to ascertain satisfaction within each interval of student’s chosen

blended learning which will be explored below. Each of the

courses utilized a hard copy and/or digital textbook to ensure ease

of access. Instructor developed Microsoft power point modules

were used to supplement the textbook and offer additional

resources and examples to ensure the retention of key concepts.

Supplemental technical reports, peer reviewed articles and online

open sourced audio-visual clips were also used to stimulate

critical thinking and problem solving skills while ensuring overlap

of important concepts and themes in the course. The course

was rigorous in a sense that students would be asked to engage

in significant reading and watching/viewing videos with a rigid

structure/ schedule to ensure timelines were maintained and

no additional time was offered for any groups of students being

studied. The course was designed to ensure consistency across

time, content and performance measurements [32]. Performance

measures included three in-class examinations (75%) and three

assignments (25%) with deadlines within the semester.

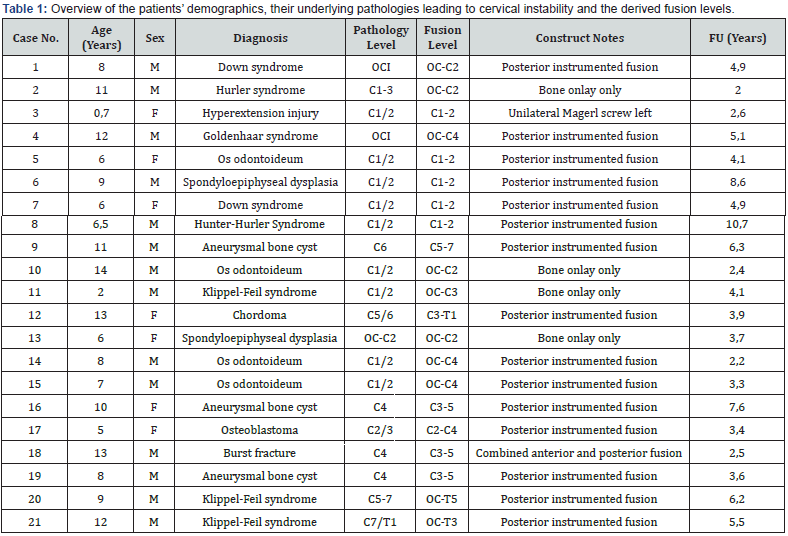

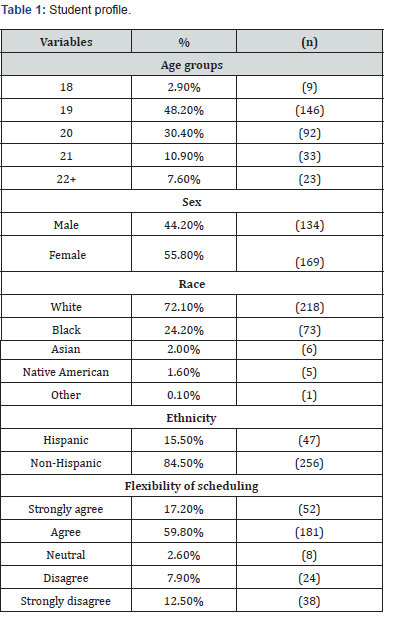

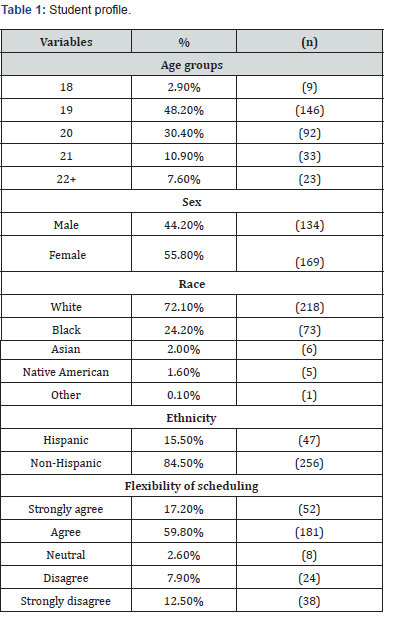

As explained previously, the study sample began with 334

eligible students enrolled in seven 200-level criminology/ criminal

justice courses within a liberal arts university in the midwestern

United States. Thirty-one students were removed from the

study for (i) having dropped or withdrawing from the course or

(ii) not completing their self-administered surveys. Therefore,

303 students were used for the analysis of this study. Students

were asked to complete a short open-ended self-administered

questionnaire at the beginning of the course. Responses were

relevant to establishing a baseline of data points to understand

the profile of the sample (Table 1 below). Table 1 provides a

general demographic profile of the 303 students enrolled in the

study. In terms of age distribution, a substantial majority (92%) of

undergraduate students were aged 21 21 or under which would

suggest that it would be typical of a traditional university 200-level

course. Women represented a larger percentage (55%) of the

students enrolled in the criminology/ criminal justice courses

which mirrored the University’s student body demographics.

The

majority of students enrolled in courses self-identified as White

(72%) and a large concentration of students self-identified as

Black and/or African American (24%). Asian (2%) and Native

American (1.6%) students were also well represented in the

course, which closely resembled the student body population of

the institution. The University campus in which these courses

were facilitated in have a diverse population across it from large

concentrations of Black and African American residents (16%)

as well as Hispanic/ Latino residents (14%) which mirrored the

student body populations of 21% and 15% respectively. Within

this study, approximately 16% of the students self- identified as

Hispanic and/or Latino. These demographic numbers on race and

ethnicity would suggest that visible minorities were slightly oversampled

in terms of their population in the area and within the

student body population. While this may have an impact on results

of the study, this profile of students was somewhat representative

of the Institution’s student body.

In an effort to test for student

motivation and needs, the pre-test questions probed for students

to reflect on whether flexibility and convenience (in time, travel

to campus) was a factor for selecting a particular form of course

instruction. A significant percentage of students enrolled in these

courses agreed (60%) or strongly agreed (17%) that flexibility and

convenience of scheduling impacted their decision on which ratio

of blended learning instruction they would select. Approximately

3% of students reported a neutral response however, over 20%

of students reported it would not affect their decision. This

might suggest a number of factors that were not studied from

whether a student was already on campus and felt more online

instruction may not be useful, that a student’s schedule did or did

not allow for revisions and whether this course should have been

introduced to students with more advance warning could have

impacted a student’s decision.

These findings would substantiate

the importance of flexibility and convenience that student’s

require and perhaps why students may consider blended or online

learning. However, as noted above, this was not an issue for nearly

one in five students. Student profile data attained from pre-test

surveys was also corroborated with a more rigorous and valid

reporting measurements attained from the University Registrar.

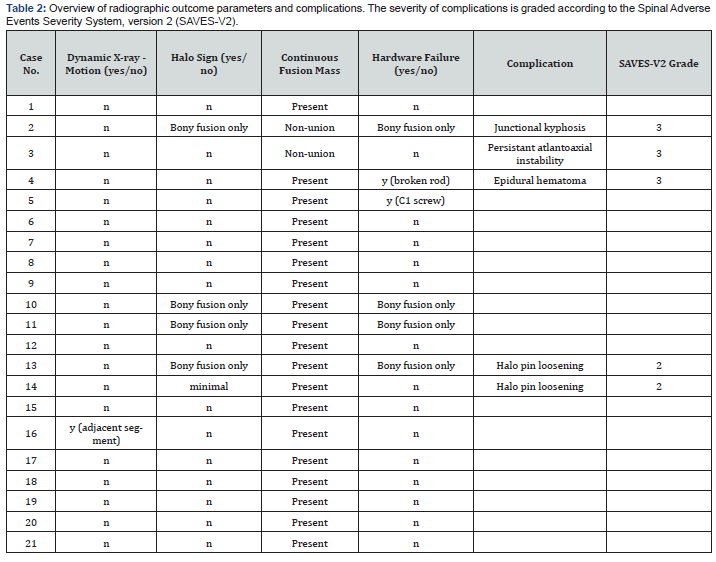

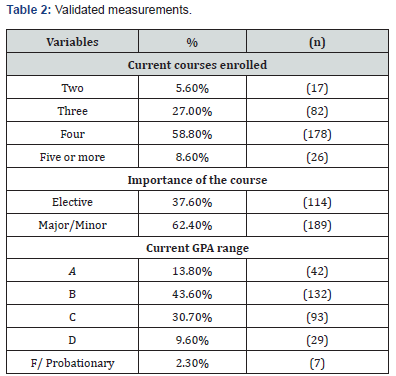

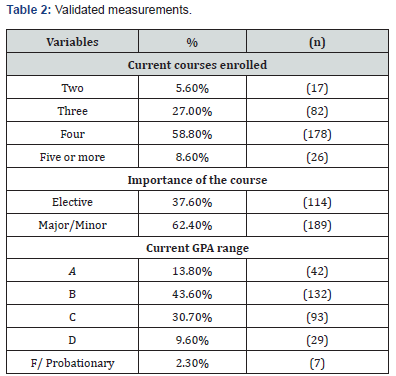

Table 2 examines the validation measurements that were used to

also generate variables of interest for further predictive analysis.

Within Table 2, undergraduate students enrolled in the seven

criminology/ criminal justice courses were asked to provide their

student number so that further variables (their current course

load, their designated field of study and current grade point

average) could be utilized as a more valid representation of their

student history at the Institution. A significant percentage of

students (94%) were currently enrolled in three or more classes,

which is considered a full-time course load. Additionally, there

were more students (8%) were taking the most courses allowed

(without permission at five courses) than those students who

were only taking two courses in the semester they were taking

this course (7%). This finding would suggest that there were

no students taking this course as their sole component of their

university workload. This would suggest (not accounting for

students who may be registered students at another university

and the University where this study was conducted) that the

findings identified in this study may be significantly different than

those studies who may be unaware or not have controlled for

course load. This is why the methodological approach within this

(exploratory) study will likely generate unique findings that could

be more consistent with traditional university students taking

larger course loads than those students who are enrolled as part

time or single course consumers.

The relative importance of the course was another variable

of interest that is often not considered particularly pertinent

or tested within the literature. Within this study, there was an

expectation that undergraduate university students who are

more likely to engage in a designated career path (in this case

criminology/ criminal justice) may feel that face to face course

work might be more ideal or are more motivated to take face to

face courses versus students who enroll in the course to fill an

elective within their liberal arts degree. This 200-level course was

a pre-requisite for additional courses within the degree program

and as such, a majority of the students (62%) had enrolled in these

seven courses to fill that pre-requisite for their major/minor of

study in criminology/ criminal justice. A smaller but still relatively

large component of the students participating in this study (38%)

had enrolled in the course either in fulfillment of their liberal arts

degree requirement, as an elective and/or not having declared

a major or minor in criminology/ criminal justice (which would

have likely occurred prior to this course). This finding would

suggest that there is still significant variance within the variable

that the author felt could be a concern for further analysis. A

final variable of interest that was validated through University

records was a student’s cumulative grade point average (GPA), A

student’s GPA would be compiled from their course work within

the University and any other courses they may have transferred

into from previous universities or colleges.

This study purposely

chose to use validated University records rather than selfreported

scores from students as they would be more reliable and

accurate considering that GPA is generally from a score of zero to

a 4.0/4.5. Once a student’s GPA was coded, it was then categorized

into University pre-determined values of an A, B, C, D and F and/or

probationary status. Most students may characterize themselves

as excellent however, a validated assessment of student GPA

found that only 14% had attained a cumulative A average. The

predominant number of students had attained a B (44%) and C

(31%) cumulative GPA. Approximately one in ten students (12%)

were considered at more high risk of poor or failing cumulative

work. Obviously, the finding here is that a large majority of

students had completed coursework in a good to fair job prior

to enrolling in the course. As such, they may be inherently more

likely to be satisfied with their previous work while also be very

concerned with their grade in this course. Throughout the survey

process, students were asked to select their mode of instructional

delivery (viewed below).

Table 3 highlights the student self-selection and/or reselection

of online instructional delivery within the seven

criminology/ criminal justice courses. As viewed above, 45%

of students preferred the 70:30 blended option of course instruction; where 70% of the course would be taught face to face

(F2F) and 30% within an online environment. Approximately

2$% enrolled in a 10% online learning environment, similarly

to 20% of students who selected a 70% online environment.

Only 10% (31) of the 303 students selected an almost entirely

90% online environment. It should be noted that at no point in

time, across all seven classes did any one student ever ask or

want to select an option of 100% face to face. While this was not

an option that students were offered, no one student even chose

to ask. This in and of itself, was an interesting finding as there

would be an expectation that if 20% of students who reported

that convenience and flexibility was not an issue, that one of those

students or perhaps other students who had performed well in

traditional face to face courses may not want to change (and/

or choose to register/ enroll in this study). As explained within

the methodology, to offer students additional flexibility and/or

a choice, students were offered the opportunity to revise their

initial blended course delivery. When provided this opportunity,

10 students revised their initial choice. This accounts for only

3% of all students.

This would suggest that 97% of students were

satisfied with their initial choice. Therefore, this study can infer

that students appear to be confident in determining which level/

ratio/ interval of online instruction they favor. This might suggest

that offering this option to traditionally based F2F courses may not

require instructors to be overly concerned about student’s ease of

access or uncertainty over their initial decision. Of the 10 students

who revised their initial instructional delivery, each of these 10

students initially chose less face to face engagement (90:10 or

30:70). When asked to re-select their desired blended course

instruction, 10 of 10 students re-selected options with more face

to face interactions. Similar to the initial student selection process,

no students wanted or preferred a re-imagined 100% face to face

course. Operationalizing Twigg’s [31] classification of blended

learning, a majority of undergraduate university students selected

a replacement (25%) or supplemental approach (48%) rather than

an emporium approach (26%). This finding suggests that students

in this study preferred higher intervals of face to face instruction

than higher ratios of online instruction. Reiterating what was

mentioned previously, no one student sought out an entirely face

to face traditional course which they originally enrolled in. These

findings would infer that students did appreciate the opportunity

to select their own instructional delivery. However, Might this

appreciation have an impact on satisfaction?

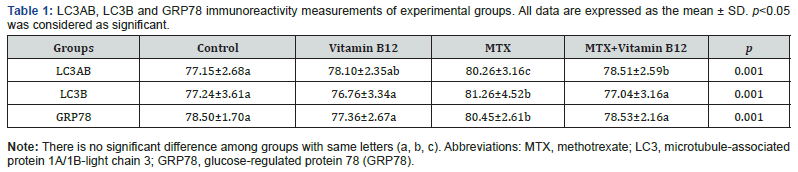

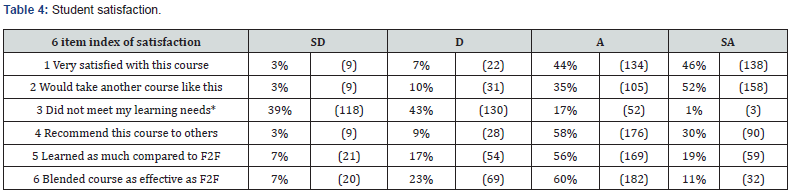

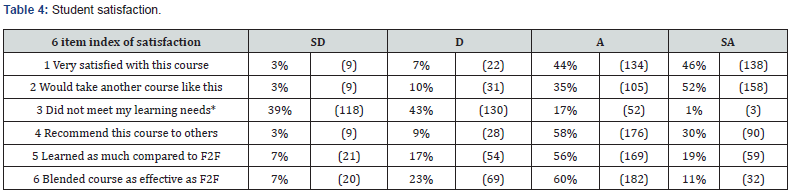

To assess student satisfaction, participating undergraduate

students were asked to complete a follow-uo post-test survey

once the course was complete and grades assigned. The six-item

index of satisfaction was developed by Strachota [33] and further

redesigned into what she coined as the Student Satisfaction Survey

(2006). Table 4 highlights the findings of the general satisfaction

of students within the sample. To pilot her survey instrument,

Strachota [8] found this general satisfaction dimension had a

reported.90 Chronbach alpha (ranging from zero to one) which

is exceptional. The findings from Table 4 indicate that students

enrolled in seven 200-level criminology/ criminal justice courses

were very satisfied with the course utilizing Stachota’s general

satisfaction survey (2006). Nine of ten students agreed or strongly

agreed with the statement that they were very satisfied with the

course while only 3% (9) of the 303 students reported being

very dissatisfied with the course. Nearly the same percentage

of students (87%) reported that they would take another selfselected

blended instructional course again if it was offered.

Further extrapolating the data, one in ten (12%) students reported

that they would not recommend this course to others. When

considering learning needs, there was significantly more variation

in student responses. Approximately eight in ten students (82%)

agreed or strongly agreed that the course met their learning needs

with 18% reporting the course did not meet their learning needs.

Three-quarters (75%) of respondents agreed or strongly agreed

with the statement that they learned as much in this course (as

compared to other face to face courses they had taken previously)

[34-40].

Interestingly, 30% of students reported that they generally

believed that blended courses would not be as effective as face to

face courses. Therefore, the student responses to satisfaction in

the course report some unusual and contradictory findings where

students appear to have been very satisfied with the course, there

were issues whether they would take another self-selected course

(despite previous frequency distributions which inferred some

level of appreciation) and/or whether the learning and instruction

met their needs. It could be concluded that perhaps the instructor’s

learning and/or instructional materials may not have matched

the expectations of students. More research is certainly need

to justify this potential inference. To assess and predict student

satisfaction, an ordinary least squares (OLS) linear regression

was utilized for further analysis. As such, survey item/ statement

three required a change in coding to ensure that each of the six

item likert scales could be aggregated from strongly disagree

(0) to strongly agree (3); within the appropriate direction. This

allowed for the generation of a larger index of scores from 0-18.

As seen in the frequency distributions above, there was enough

variability in each of the variable to make conclusions about the

potential relationship of that variable (age, sex, race, flexibility,

course load, fulfillment of course credit, GPA and student choice of

course instruction) and general satisfaction. Student self-selection

was coded appropriately from low online instructional delivery to

high) [41-50]. The OLS regression data is below.

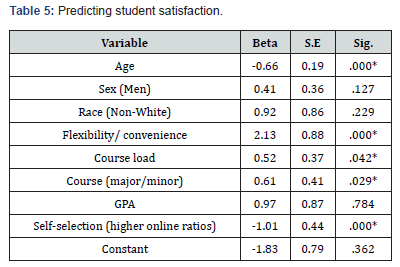

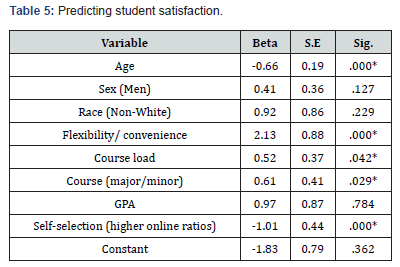

The linear regression model, located in Table 5, was found to

be statistically significant (.001 with a confidence level of 95%

with the p < .05 being significantly different than zero). Student

self-selection and seven variables of interest were found to explain

48% of student satisfaction based on the Nagelkerke R Square

(.482). The regression reported a Chi-square of 209.46 and a model

-2 Log likelihood of 111.29 (with 8 degrees of freedom). Four

cases were removed from the analysis when the variance inflation

factor (VIF >4) and tolerance (TOL) levels of 2.0 or above were

controlled for. Student self – selection of instructional delivery

was found to be the second most important variable to predict

student satisfaction. This finding would suggest that the lower

the ratio of online blended learning, the higher the likelihood of

student satisfaction. Put another way, the higher the percentage

of independent or online learning within courses, the more likely

students in this sample would be dissatisfied. This finding suggests

that as interval levels of blended learning increase, it can have a

detrimental effect on student satisfaction. This might suggest that

not all blended learning is the same and that there may be tipping

points where satisfaction may become dissatisfaction. However,

it should be noted that student choice of instructional delivery

was not the only statistically significant variable within the model

(based on the Beta values) [51-59].

The most significant predictor of the course satisfaction

regression model was the flexibility and convenience of the course

offerings. This is consistent with previous research in the field in

that blended learning courses can predict student satisfaction.

This suggests that not only is flexibility important in scheduling

but additionally, that those students who enroll in more courses

within a semester are more likely to be satisfied than students

who enroll in lower numbers of courses simultaneously. The

evidence, supported by the data, suggests that age was also a

predictor of satisfaction. It appears that older students who

participated in the study were more likely than younger adults

to be dissatisfied with the course. This is somewhat surprising as

it could be hypothesized that older students may be more likely

to require more flexibility and convenience (due to employment,

child care, etc.). However, this could be a case where ease of use

(as explored in the literature) may have been an impact variable

rather than age. Other demographic variables including sex and

race were found to not have any statistical significance within the

model. This is consistent with some of the research findings [16].

Students with higher course loads appeared to be more satisfied

with the course. This could be due to the opportunity to have a

more balanced and/or flexible schedule however, it is more likely

that attaining more course independent time to complete work

and assignments had an impact. However, more research is needed

before this can be verified but it is certainly an interesting finding.

A finding not often examined in the research is whether student

interest or motivation, as denoted by a student’s major or minor

level of study, has an impact on their reported satisfaction. The

data suggests that students who had declared a major or minor in

the study of criminology/ criminal justice were more likely to be

satisfied with the 200-level criminology/ criminal justice course

they enrolled in. Therefore, students who utilized this course as an

elective for their liberal arts degree were less likely to be satisfied

with the course. This might suggest that how the instructor

constructed this course may have inherently benefitted students

who declared a major or minor in the field of interest versus those

who may have had less interest in the course content. Obviously

more research is necessary to understand how student motivation

impacts satisfaction.

As an exploratory case study, the findings of this

research

would suggest that more examination of blended learning and

intervals/ratios of blended learning need to be examined. Simply

offering blended learning does not have an impact on course

satisfaction (as all forms of instructional delivery in this study had

some form of online delivery). This would suggest that there is a

tipping point where students find satisfaction with the blended

offering but too much blended learning (using the instructional

delivery explained within the methods section) has an inverse

relationship to student satisfaction. This study finds that student

selected ratios or intervals of blended learning that offer more face

to face interaction rather than less result in higher levels of student

satisfaction. This finding would certainly suggest that while

students appreciate the convenience and flexibility of hybrid and

blended instruction, they still want (in this instructor’s course)

face to face interactions. Therefore, when constructing courses,

instructors should be diligent to ensure that they are present

and that students receive that face to face time (that even digital

recordings are unable to capture). That rapport and relationship

building appears to be important to student satisfaction in this

study (however more in-depth research is needed). However, as

expressed in the literature review, there is no perfect one size fits

all strategy to implement blended learning as each instructor will

construct their own course, based on their needs and the needs of

their students.

As referenced in the literature, convenience and flexibility

remains a significant factor when understanding the circumstances

students face and satisfaction within their courses. This also may

hold true for instructors as well. With a relatively good variance

explained within the model, there appears to be hope on the

horizon that the use of this a consistent construction and design

of a course could reap benefits with instructors and students alike

(without significant revision each year). While more research is

needed to identify more conclusive findings, blended learning is

an increasingly attractive alternative to traditional face to face

or online learning and has a significant impact on a student’s or

consumer’s satisfaction particularly post-COVID-19. As students

continue to search their desired instructional delivery it would

be wise that instructors consider offering more choice and

selection to ensure each student can attain their desired learning

interactions within the same class based on their motivations.

Allowing student self-selection also might alleviate the finding

that with more online instruction, Allowing student discretion to

make their instructional delivery selection places more emphasis

on their decision making rather than potentially blaming one form

of instructional delivery over another. Despite these findings,

it is clear that more research is needed on intervals of blended

learning, stronger comparison groups and how student selection

impacts not simply student satisfaction but also grade attainment

and/or other measures of student success.

To Know more about Annals of Social Sciences & Management Studies

Click here: https://juniperpublishers.com/index.php