Physical Fitness, Medicine & Treatment in Sports - Juniper Publishers

Abstract

British Equestrian (BE) aims to develop a holistic coach education and certification program, moving away from traditional autocratic instruction in line with the United Kingdom (UK) Coaching Framework. This framework is based on generic coaching science research where the coach is cited as a pivotal aspect in developing sporting success. Theoretic knowledge suggests that the role of the sports coach is to develop the physical, tactical, technical and psychological attributes of the athlete and is responsible for the planning, organization and delivery of the training plan and competition schedule. However, there is no empirical evidence to suggest that is the role required in equestrian sport, as the rider often takes responsibility for many of these tasks. This research aimed to address the void in current knowledge by gaining an understanding of coaching in equestrian sport at the elite level, to improve coaching education systems through awareness of the role of the coach. A qualitative method using semi-structured interviews was used. A sample of elite coaches (N=3) and elite riders (N=3) were interviewed. Analysis of the transcripts revealed a total of 534 meaning units that were further grouped into sub-themes and general themes from the coaches’ perspective and the riders’ perspective. This led to the development of a final thematic structure revealing major dimensions that characterized coaching in elite equestrian sport. It was found that the riders at the elite level, coach themselves most of the time therefore can be considered as ‘self-coached’ athletes. However, they do use elite coaches in a mentoring and consultancy role, where they seek guidance from the coach on specific problems, to sound ideas off or to seek reassurance that what they are doing is correct. Findings from this research suggest that the rider-coach relationship at the elite level is a professional one, based on trust and respect, but not a close relationship, as seen in other sports. The results show the imperative need for the BE to educate coaches in coaching the self-coached rider at the elite level, particularly in terms of mentoring skills. As well as incorporating rider education aimed at developing the independent, self-coached riders.

Keywords: Coach; Elite; Equestrian sport

Introduction

Equestrian sporting origins are deeply rooted in military tradition, both in the development of the sport and the training of the horse and rider. Equestrian sports are unique as they test the rider’s mastery over the horse in terms of athleticism, control, and accuracy. British Equestrian (BE), the umbrella governing body of equestrian sport, represents 10 sports including the Olympic disciplines of evening, Show Jumping and Dressage. It works to promote the interests of 3 million riders and carriage drivers in the United Kingdom. The Federation is responsible for distributing government funds from UK Sport with an aim to win more medals on the world stage and to get more people participating in equestrian sports. BE places the coach as an integral part in achieving these aims. Substantial sports coaching literature has identified the importance of the role of the coach in sporting success as they are pivotal in the development of physical, tactical, technical, and psychological attributes of the athlete. However, equally important is the role the coach plays in the overall enjoyment, satisfaction and ultimately retention of people participating in the sporting activity. The basic role of any sport coach is to develop and improve the sporting performance of the team or individual. However, as participation in sport is usually voluntary, the experiences encountered can make or break a participant’s continuation in the sport. If the experience is not satisfactory, they are likely to leave the sport. The coach is therefore the key component to whether the activity is positive, and the quality of this experience depends on the coach’s value, principles, and beliefs.

It is acknowledged that the role of the coach is diverse and often not fully understood. Indeed, modern day coaching practitioners are not only responsible for directing practice and training sessions but also for the overall social and psychological well-being of their athlete both inside and outside of the sporting arena. Therefore, as [1] points out, to fully understand the role of the coach a critical analysis is needed of the nuances, actions, behaviour, and complexities used by sport specific coaching practitioners. This suggests that there needs to be recognition of the layers of skill and competencies required, how these interact with each other and how they impact on performance. Research has identified that successful coaches across a range of sports have several qualities in common: the ability to select the most important leadership behaviour; a personal desire to foster individuals’ growth; organizational skills in planning and preparation; a strong sense of goals, philosophy, and personality. This indicates that coaching cannot be viewed as purely a series of actions but a complex model of overlapping aspects. Research supports this by suggesting that coaches require additional skills above the technical knowledge of their sport and that these include pedagogical skills of a teacher, counselling skills of a psychologist, fitness training skills of a physiologist and the administrative and leadership skills of a business executive [2] also includes the role of a mentor and pillar of support to the athlete [3] clarifies the practice of coaching as a complex, dynamic, social domain and context dependent enterprise with often contradictory goals and values. Understanding these complexities is key to evaluating the purpose of the coach, needed in coach education to develop and improve coaching skills. The training of coaches is seen as essential to sustaining and improving the quality of coaching and on-going professionalism. Yet, [4] points out that currently coach development programs use a competency-based approach. This is, in fact, true of the BE who have developed a certification program in line with UK Sport’s United Kingdom Coaching Certification (UKCC). This is a move away from the traditional autocratic style ‘instructor’ to an ‘athlete-centered’, holistic approach to coaching. The traditional system, whilst acknowledged worldwide as a comprehensive program developing basic riding skills was an authoritarian approach to teaching riding. The syllabus was based on the ‘classical’ tradition of training horses based in the military past and lacked scientific validity. The current focus on the holistic approach and the development of an athlete, is supported in other areas of coaching, physical education and indeed education. A strong athlete-centered coaching approach emphasizing the development of self-confidence and belief in one’s ability is essential in making the correct decisions in a competitive situation. Producing ‘independent learners’ and ‘independent ‘decision markers’; may be key to the equestrian model as the rider is often considered as the ‘leader’ and non-verbal decision maker of the team.

Decisions made during riding must be made quickly and have dynamic consequences. The rider must calculate so many variables and translate them to effective communication with the horse. The rider needs to make the correct decisions at the right time and failure to make correct decisions can be catastrophic. This requires quick cognitive function, complex tasks, and choice reaction times. Indeed, it is this quick proprioceptive processing and effective decision making that are key to effective horse riding. This can only be achieved if the rider is empowered to be independent leaders that are confident decision makers. Olympic rider and coach, Phillip Dutton agrees: “You need to be strong and independent enough so you can ride without an instructor watching you all the time, holding your hand, and doing everything for you. Eventing is a sport where you are out there on your own especially cross-country phase. Your instructor may help you gain skills and improve your riding, but you must develop your mind and confidence so that when you are on course you can do it on your own [5].

To attain this holistic approach to coaching a substantial amount of literature has revealed the importance of the coach-athlete relationship and that the strength of this relationship should be based on closeness, co-orientation, and complementarity (3Cs). However, literature, mainly popular and non-academic, suggests that it is the rider that is responsible for the training of the horse in terms of fitness, skill, and technique as well as the management and wellbeing of the horse. They also assume the planning of competition schedules as well as most of the tactical and technical support, therefore it can be assumed that in part, they coach themselves. There is little empirical research to identify what the role of the equestrian coach is in this triad relationship. Therefore, the aim of the study was to gain an understanding of the role of the coach in elite equestrian sport to improve coaching education systems through awareness of the role of the coach. The first objective was to examine the relationship between coach and rider at elite level in equestrian sport providing empirical evidence to suggest that the rider is, in part, ‘self-coached’. The second objective was to identify what elite equestrian coaches believed their role is in the development of safe and effective riders.

Method

Sampling

The research question was developed with regards to elite equestrian coaches and riders as the study of their inferences could be drawn and applied to coach education. As there is no cohesive definition of an expert coach or valid ways to identify expertise, almost all research relies on years of experience or level of performance. As this study formulates primary research in the field of equestrian coaching and due to the large number of variables associated with the sport a top-down approach researching the elite level was chosen. Therefore, the principles of purposeful sampling were implemented using the following criteria: Three elite equestrian coaches were selected who were currently coaching on the BEF World Class Programme and working with GB senior team riders competing at the international level. A list of subjects that met the criteria, were drawn up and were approached based on location to researcher. One female coach and two male coaches were interviewed, one specialised in dressage, one show jumping and one in eventing, although all had had experience of coaching event riders. All were known in a professional manner to the researcher. Three elite riders were selected using the following criteria: member of the BEF World Class Programme and had represented Team GB at senior level during the past year. Three riders were selected from a possible 32 across the disciplines of eventing, dressage and show jumping. Two riders competed in eventing, one in the discipline of Show Jumping and were selected on location to researcher and were also known in a professional manner to the researcher.

Instrument

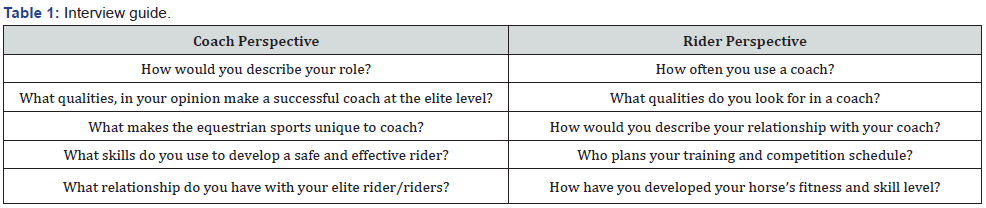

A semi-structured interview schedule that prompted responses to open ended questions about the roles and relationships of coach and rider was chosen as the method for this study. A semi-structured interview guide (Table 1 & 2) was developed to allow the interviewer to explore the relationships and roles within the coaching process. Participants were informed that there were no right or wrong answers, they were asked to take their time to respond to questions or to tell the interviewer if they did not understand the question. In addition to the semistructured questions specific probes were identified for each question and encouraged participants to elaborate on their responses.

Data collection

Coaches and riders were approached via phone call or email by the author and invited to participate in the study. After explanation of the aims and background of the study, interviews were arranged at a time and place elected by the interviewee. The interviews ranged from 25-55mins and were audiotaped with participants’ consent. The interviews were later transcribed verbatim into A4 single-spaced text.

Pilot study

A pilot study was carried out to assess the effectiveness of the questions selected. One elite coach was selected to be interviewed. Responses were forthcoming and met expectations. However, to validate the results further it was decided to also interview riders to gain their perspective of the role of the coach and the relationship they have with their coach. A further pilot interview was carried out with an elite rider to again assess the effectiveness of the questions selected.

Data analysis

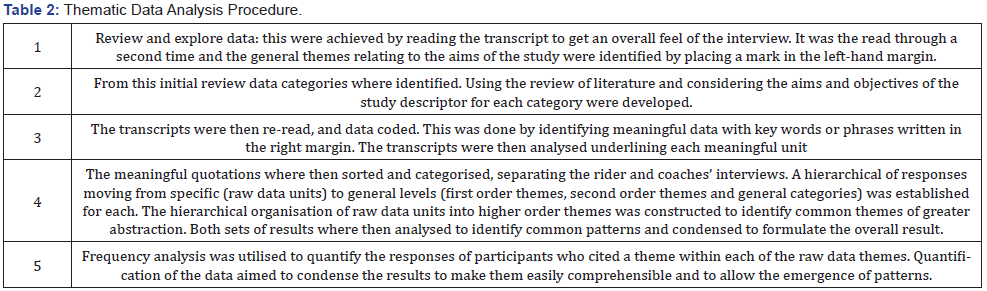

Thematic Analysis was used as a systematic method for exploring the contents of the obtained data.

Ethics & Limitations

Ethical approval was granted by Hartpury University. The interviewees remained anonymous and confidential throughout the study, however, due to the high-profile nature of the sample it may be possible for people in the equine industry to identify subjects from their responses, however all efforts were made to retain anonymity and participants were given a letter and number as a means of identification through the study. Questioning topics did not cover intrusive or overtly personal subject areas. All participants were over the age of 18 and choose to take part under their own free will and were able to withdraw from the study at any time. Informed consent from the coach and riders were obtained prior to the interviews being recorded. The Data, both audio recordings and transcripts were stored in accordance with the Data Protection Act 1998.

The limitations of using a semi structured interview technique are that not all people are equally cooperative, articulate, and perceptive. The interviewer requires skill, not only to select and ask the appropriate questions clearly, but to gain the interviewees trust and confidence for them to elicit a full and honest response.

As a result, it is not a natural tool for gathering data as it requires interaction between two parties. However, due to knowledge level and experience of the researcher regarding equine performance these limitations are reduced.

Results

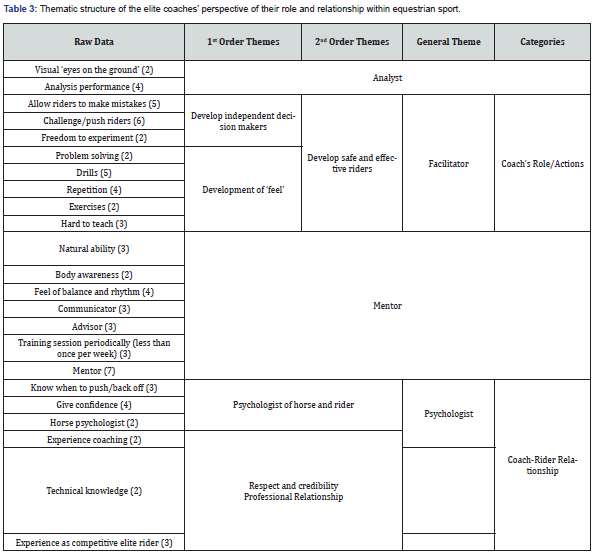

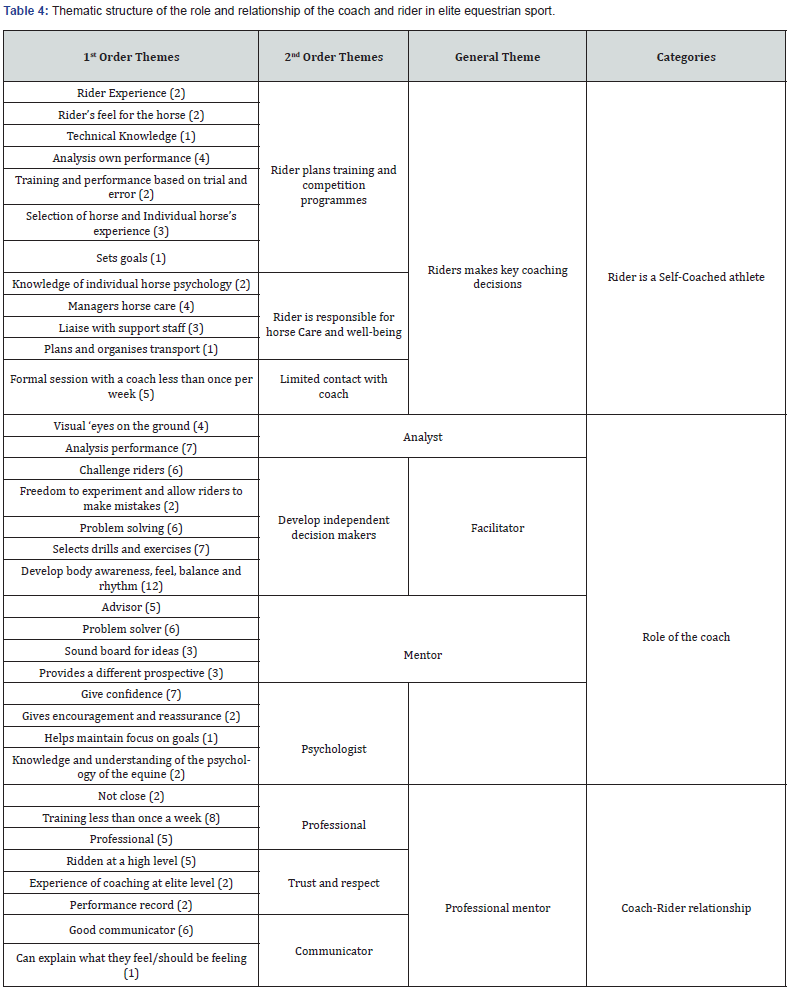

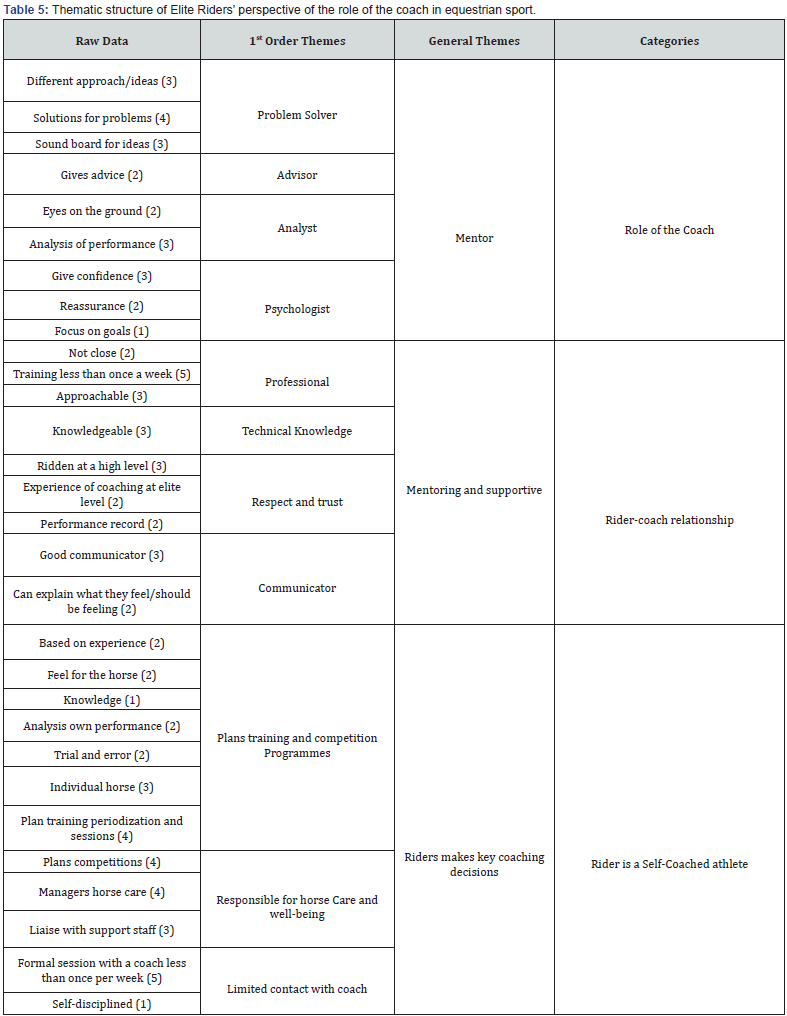

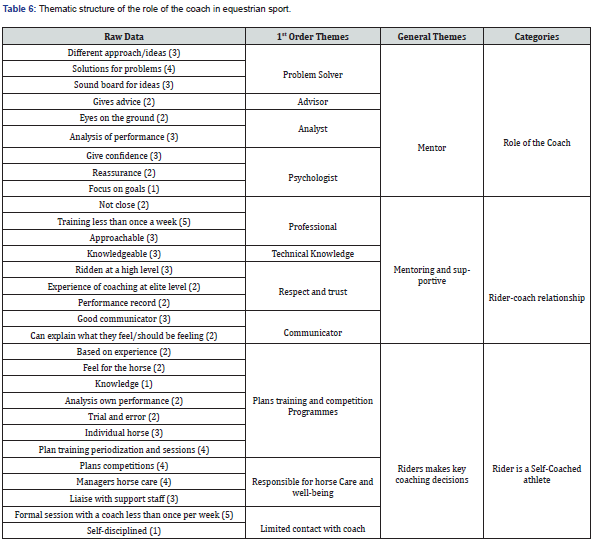

Analysis of the transcripts revealed a total of 534 meaning units that were further grouped into sub-themes and general themes from the coaches’ perspective (Table 3) and the riders’ perspective (Table 4). This led to the development of a final thematic structure revealing major dimensions that characterized coaching in elite equestrian sport (Table 5 & 6).

Discussion

Self-coach athletes

Analysis of data suggests that riders at the elite level in equestrian sport are in part ‘self-coached’. The results of the study show that riders attend a training session with a coach less than once a week and some as little as once a month. The remaining time the individual rider is responsible for all training decisions including horse selection; competition planning; implementation of periodization plans; management of support staff. Training decisions are made by the riders based on experience and knowledge of the individual horse. Therefore, in depth knowledge is needed by the rider in all areas. The development of the equestrian UKCC qualifications has incorporated the importance of planning for the coach but fails to acknowledge that it is the rider that plans the program. It was acknowledged by both the riders and coaches that consideration for the horse’s wellbeing and ensuring they were willing to do the task being asked was a key factor in their planning. This is because the equine has no concept of the goals involved. Coach C1 clarified this by stating “It is better to have the horse 90% prepared or 90% fit and 10% willing than have 100% prepared but you have no willingness”. This is in direct contrast to literature in other sports where being 100% prepared is necessary for sporting success. Therefore, any equestrian plan needs to suit the temperament of the horse. The results highlighted that knowledge and understanding of the psychology of the individual horse was significant and that as the rider has a close relationship with their horse, they are in the best position to make these training decisions. However, the equestrian UKCC syllabus does not incorporate any aspect of equine psychology or horse management, although these topics are still present in the other equine coach certification systems.

All riders in the study identified that how the horse ‘feels’ is the deciding factor in increasing intensity of training or increase in competition level, this suggests that there is an element of reflective analysis occurring and highlights the importance for developing and understanding this concept of ‘feel’. Yet there was no evidence to suggest riders use an objective analysis approach, this may be due to lack of knowledge by the rider and lack of research reaching the industry e.g., use of heart rate monitors, biomechanical analysis etc. There is also a lack of consistency both in literature and amongst the participants as to what actually constitutes ‘feel’. More research is needed to define this concept in equestrian sport and how it is developed to enable it to be taught or coached more effectively.

During their self-coaching training, all riders stated that they used outside observers either grooms, family members or friends to gain feedback. However, the quality of these observers is unknown. This is an area that requires focus and providing quality education to this support team needs consideration. A greater understanding of the self-coached riders is needed to fully feed into education programs for riders at all levels as well as an understanding of how the coach can support the self-coached rider optimally.

Coach-rider relationship

Current research in the field of coaching science recognizes that sport is not immune from the social world and that to examine the dynamic coaching process contextual social factors must be considered. Indeed, any activity that involves human beings is complex, interpersonal and that relationships are contested at levels of meaning, value, and practices. The relationship between the coach and the athlete is not an add-on or by-product of the coaching process but could be considered the foundation of coaching. Therefore, the coach-athlete relationship can be defined by mutual and casual interdependence between coaches and athlete feelings, thoughts, and behaviour, suggesting shared goals and values [6] proposed that successful coach athlete relationships are based on four concepts: closeness (trust and respect); commitment (shared goals and connection); complementarity (interaction that is co-operative and effective); co-orientation (acceptance of individual roles). However, previously there is no evidence to suggest these are used in equestrian sport.

The interpersonal relationship between athlete and coach plays a significant role in the sporting lives of the athlete and is likely to determine satisfaction in the sport, self-esteem and confidence and ultimately successful sporting performance.

However, knowledge and understanding of these relationships remains limited at both the theoretical and empirical level. This study elucidated that the relationship between the coach and rider was a professional one that could be described as reciprocal, yet asymmetrical characterised by a unique relationship between individuals and depended upon experience and age difference. This study revealed riders sought a coach that was approachable, that they felt comfortable discussing ideas with and that they trusted and respected. This view is supported in other sports; however, the riders did not describe the relationship as ‘close’. Yet closeness is considered by Jowett’s 3Cs as a key component of the in successful coach-athlete relationships. This may be in part due to the limited contact riders have with their coaches. Contact was mixed amongst the subjects; one respondent only saw their coach during periodic World Class training which may explain why their relation was not considered ‘close’. Further research is needed to fully quantify the ‘norm’ for contact time with coaches across equestrian sport at varied rider levels.

Respect and trust

The emerging themes that were expressed by the rider participants show some commonality in their lower order themes, that they desire a coach that they trust and respect. All participants claimed that this respect was generated from the coaches’ own riding experience and level in which they had competed. It was felt that this was needed to not only have credibility but also to have the knowledge of riding a variety of horses at the elite level and to have the appropriate repertoire of training solutions. The ability to have the concept of ‘feel’ of the individual horse was also deemed important. One participant commented that: “It is also really useful for them to get on the horse so they can feel what I feel” R1. This suggests that equestrian coaching is largely experienced-linked and situation-specific base, like that required in the sport of sailing. Such an important statement is worthy of further investigation as other equestrian coaching qualifications include riding tests as part of their qualification curriculum, whereas the UKCC does not. Interestingly the elite coaches acknowledge the advantage of riding experience for a successful coach but felt that this was not necessary. This is supported in other sports where the best coaches are not always elite athletes but have had experience of competing just below the elite level, this may well not be applicable in equestrian coaching at elite level.

Mentor relationship

Riders in this study referred to their chosen coach when they needed advice or mentoring. One way by which the riders identified this mentoring relationship was that they used a coach as a sounding board for ideas. This was, in part, used to gain confidence and reassurance in the knowledge that what they were doing was correct. They also used the coach as a mentor when they had a particular problem or needed a fresh approach to a particular horse or situation. Whilst BE acknowledges the importance of mentoring skills within coaching, it fails to clarify what these skills actually are, yet it can be accepted that it is a form of supported learning through social interaction. Evidence from these interviews suggests this is achieved through a shift between support and challenge.

Facilitator in the development of safe and effective riders

[7] when analysing relationships within the caring professions, identified good mentors as challenge givers, the collective viewpoint expressed by the participants indeed concurs with this within this study. Emphasis was placed on the element of challenging the rider. This may be since in the remaining time the riders are self-coaching and may not be motivated or confident to push themselves outside their comfort zone. C1 expressed this view “that they go over what they are comfortable doing and that they are good at” C1 29-30. Within this study the findings concluded that the elite equestrian coaches facilitated this challenging environment by setting up exercises that allow riders to experiment, for example, different approaches to jumping a combination. This suggests a move away from skill practice to development of perception and decision-making processes. This allowed the riders to make mistakes and learn from these mistakes. The coaches in this study stated that they achieve a learning experience by discuss those mistakes, getting them to think how they would ride the exercise differently and creating awareness of feel in relation to position. This cognitive action through a guided discovery approach achieves an empowerment process.

Similarly, to other sports, feel or body awareness in equestrian sports is achieved through drills and repetition. Riders felt this fed into positively developing their own confidence, improving their cognitive awareness and automatic decision-making processes. More research is needed in this area to understand which exercise or drills are the most effective in developing this aspect within equestrian coaching.

Recommendations

The results from this study provide substantial evidence for the need to incorporate the topic of coaching the self-coached rider into equestrian coaching education systems at elite level. Coaches should be aware of the demands and limitations of coaching the self-coached rider and appreciate the importance of their role in the successful outcome of the horse/rider dyad in equestrian competition. BE should highlight and develop the role of the coach as a mentor to self-coached riders at the elite level. Amalgamation of both phases of this study combined with the themes that emerged from the interviews provides the following recommendations:

a) Role of the coach in Equestrian UKCC education should be clearly identified

b) Further development of mentoring skills of coaches

c) Identification of techniques that facilitate the development of ‘self-aware’ and ‘self-reliant’ effective decisionmaking riders

d) Development of rider skills to self-coach in terms of planning and implementing training, developing all areas of psychology, equine psychology, injury prevention etc. and analysis

e) Increasing the use of tools to enable the self-coached rider to analyse performance in both training and competition environment

Limitations of Study and Future Research

It is important to highlight the limitations inherent in the study which must be considered against the results that emerged. The sample size used in the study was small (coaches N=3, riders N=3) however, the selection criteria was carefully applied and even though the sample size was small it could justifiably be seen as offering expert opinions therefore, the findings are directly applicable to elite coaches and riders. Future research is required with differing levels of riders and equestrian coaches working to provide validity across all equestrian participants. More indepth research is indicated investigating individual equestrian sports in greater detail to examine any differences that may arise in each discipline. As expected, with any attempt to summarize or condense findings from the semi-structured interviews, not all participants were as forthcoming as each other and did not respond in the same way or to the same extent to the identified themes. The practical coaching processes were not quantified, therefore this study relied on the participants perception of coaching and the role of the coach, whilst this is a legitimate form of qualitative research the study could have included coaching observations. using video analysis to evaluate the coaching process and identify evidence of the coaching roles displayed in practice [8-54].

Conclusion

In equestrian sports there is a unique triad relationship between the horse, rider, and coach. The rider assumes many responsibilities that are undertaken by the coach in other sports, such as planning training schedules, nutrition, competition schedule, tactics etc. As a result, we can consider the elite rider often as a self-coached athlete. The findings of this study were that elite equestrian athletes therefore used a coach primarily as a mentor and that this mentoring role includes problem solving and reassurance that the training and management techniques being used are correct. Within the coached training sessions, the coach assumed the role of a facilitator, challenging the riders in a holistic manner with a specific aim to develop independent decision makers. In this study riders felt that their relationship with their coach was one of a professional nature and that they selected a coach that they trusted and respected. This was based on the level and experience of the coach as a competitive rider. This has implication on the current BE coach certification system that does not assess riding ability. Considering these findings, the BE needs to address coach education in terms of holistic practice, specifically regarding coaching the self-coached rider. Further research is indicated, establishing links between riders’ natural ‘feel’ and the development of correct decision making in equestrian sport. This will enable a better understanding of how the BE can develop coaches who will successfully facilitate and mentor essential and equestrian specific skills at all levels and across all disciplines.

To Know more about Journal of Physical Fitness, Medicine & Treatment in Sports

Click here: https://juniperpublishers.com/jpfmts/index.php

To Know more about our Juniper Publishers

Click here: https://juniperpublishers.com/index.php

No comments:

Post a Comment