Purpose: Empirical examination of the

moderating influence of dogmatism (DG) on the relationship between adult

attention deficit (AAD) and operational (traditional) project manager

effectiveness (OPME).

Design/methodology/approach: 160 actively

employed business graduate students participated in a business courses

where they were assigned to 4-person project teams responsible for

completing a major business project. The project contained 4

sub-projects each of which was managed by a different team member. At

the end of semester each team member rated the others on their project

management effectiveness. Each subject completed a self-report measure

of dogmatism and identified a close associate who completed an observer

version of the Brown Attention Deficit Scale. Linear regression was used

to test the hypothesis that DG moderates the relationship between AAD

and OPME.

Findings: DG is a statistically significant

moderator of the relationship between AAD and OPME. The negative

relationship between AAD and OPME significantly declines as DG

increases.

Research limitations/implications: Future

research requires use of samples that are more directly associated with

the workplace. Further investigation of the impact of AAD symptoms,

including potentially positive manifestations like entre/intrapreneurial

cognition and creativity, is needed to fully understand the impact of

the disorder within the project management nomological network.

Practical implications: Organizations need to

be aware of the impact of AAD and DG on OPME. The provision of adapted

project management training, productivity tools, a workspace free of

unnecessary distractions and both professional and peer coaching is

suggested for disordered project managers and participants.

Organizations need to help disordered employees find substitutes for

dogmatic thinking processes that possess similar protective and

decision-making benefits but avoid the related inflexibility and social

challenges. Employee assistance programs that raise awareness and

provide access to assessment are an important part of multimodal

management of the disorder in the workplace.

Social implications: Employers are facing

increasing social, legal and economic pressures to support and make

effective use of functional but disordered employees. This research

provides constructive suggestions for how to accommodate and support

disordered project managers.

Originality/value: This is the first empirical

examination of the relationships between AAD, DG and OPME and is of

value to researchers, organizational development specialists, human

resource management specialists, managers and employees who are seeking

effective multimodal management of attention related disorders in the

workplace.

Keywords:

Attention deficit disorder; Adult attention deficit; Adult attention

deficit disorder; Attention deficit hyperactivity-impulsivity disorder;

Adult attention deficit hyperactivity-impulsivity disorder; Project

management; Project manager performance; Project manager effectiveness;

Dogmatism

At least 5% of the adult global population have

clinical levels of attention deficit disorders [1] costing the global

economy approximately 144 million days of lost production per annum [2].

Changing role requirements for many workers is delegating and

distributing increasingly complex responsibilities and associated

competencies throughout organizations [3]. These new role requirements

are dependent on higher order cognitive processes often disrupted by

adult attention deficit disorders (AADDs) [4,5]. Managing this challenge

requires research on how AADDs

influence individual and team performance [6].

Working conditions that engage more complex higher order

cognitive processes intensifies the need for coping responses

among disordered adults [7]. Recent research suggests that

disordered adults develop rigid attachments to particular sets

of beliefs in order to constrain the extent to which self-directing

(higher order) cognitive processes are disrupted by external or

internal stimulus [8].

This research study examines the moderating influence of

dogmatism on the relationship between adult attention deficit

(AAD) and the operational effectiveness of project managers

(OEPM), the component of project management most dependent

on the higher order cognitive processes typically disrupted by

AAD.

Research conducted by Brown [9] on symptoms that

commonly occur among adults with attention deficits produced

the following 5 symptom clusters (factors):

a) difficulty activating and organizing to work (difficulty

getting organized and started on tasks predominantly caused by a

relative higher arousal threshold and/or chronic anxiety).

b) difficulty sustaining attention and concentration

(difficulties staying focused on priority tasks that are not of high

personal interest, receiving and organizing information and

resisting distraction).

c) difficulty sustaining energy and effort (insufficient and/

or inconsistent levels of general energy and difficulty sustaining

effort required to complete important tasks).

d) difficulty managing emotional interference (difficulty

with intense, negative and disruptive mood states; relatively

high and sustained levels of irritability and emotional reactivity;

difficulty managing emotions that constrain the development of

constructive relationships).

e) difficulty utilizing working memory and accessing/

recalling learned material (episodic or consistent chronic

forgetfulness, difficulty organizing, sequencing and retaining

information in short term memory, and problems accessing and

using learned material).

Brown [9] uses dimensional (gradations of severity) as

opposed categorical (non-disordered vs disordered) measurement

of the symptom clusters to determine the overall level of AAD. This

is consistent with evidence that AAD symptoms and associated

impairment fall along a continuum [10,11]. AAD is defined as a

persistent pattern of inattention and related cognitive, emotional

and effort related symptoms that occur with varying levels of

severity and creates progressively greater challenges within the

personal, academic and work life of adults as severity increases [9,12]. The use of dimensional measurement and correlational

analysis helps to reveal the influence of AAD within nomological

networks that influence organizational behavior [12,13].

Research studies using dimensional measurement of AAD has

identified associations with difficulty with teamwork [14-16];

greater reliance on co-workers [17] difficulty managing conflict

[16], increased stress [18], lower self-efficacy [18] and less

effective task management systems [15].

Attention related disorders are also associated with positive

behaviors like the ability to work in a fast paced environment,

ingenuity, innovation, creativity, determination, perseverance,

risk taking and intense focus on things of interest [19,20] which

may explain why entrepreneurs appear to have significantly

higher prevalence rates [19]. Recent research by White & Shah

[21] suggests that the disorder is associated with higher overall

levels of creative achievement across a variety of occupational and

task domains.

The ability of an organization to foster employee

innovativeness, creativity and an entre/intrapreneurial

orientation may be one of the most significant contributors to

sustained organizational success within an increasingly globalized

economy [22]. Research by Zhou [23] suggests that employees

with low creativity benefit from working closely with highly

creative employees. Organizational innovation, creativity and

success is therefore potentially influenced by the manner in which

highly creative employees, many of whom may be disordered to

varying degrees, are distributed and deployed throughout the

organization.

Managerial strategies that appropriately leverage the

potential strengths of the disorder while removing, reducing or

mitigating the deficits are needed to ensure successful deployment

of disordered employees. Most researchers and practitioners

agree that multimodal management of the disorder involving a

combination of medicinal and non-medicinal support (counseling,

coaching, training, supportive conditions and conditions aligned

with strengths) has the greatest potential for success [24]. This

requires a comprehensive understanding of the impact of the

disorder on personal performance capacity (core workplace

competencies, motivation and other performance supporting

personal states); performance behavior including key mediators

and moderators; and performance outcomes at the individual and

team level [17].

Definition and impact

Project management is defined as the application of

knowledge, skills and techniques for executing a temporary

endeavor undertaken to create a unique product, service or result

[25]. The project management process (cycle) includes a variety

of phases or stages that are often dependent on the type of project but

typically include the stages of initiating, planning, executing,

monitoring and controlling, handing off and closing the project

[26].

There are a wide variety of project types determined by the

nature of the output (e.g. building a skyscraper, developing a new

engine, designing and delivering a training service, producing

a software update etc.), the size of the project (e.g. scope,

number of stakeholders etc.), the execution culture (numerous

stakeholder checks due to security issues, established and

standardized processes, high level of execution autonomy etc.)

and the conditions within which project execution occurs (e.g.

industry, sector, organizational culture, time pressures, resource

constraints etc.). Projects are also completed by either individuals

or teams. In an attempt to identify the key differentiating features

of projects, Shanhar & Dvir [27] and others have suggested the

following general differentiating dimensions:

a) complexity (extent of scope, number of elements that

must be considered when making project decisions, project

organization requirements, number and nature of constraints

that must be addressed, number of participants and stakeholders,

diversity of output requirements and success criteria).

b) uncertainty (degree of clarity about project goals and

execution requirements, rate and degree of change influencing

project goals and execution requirements).

c) technology (level of technology required to support the

project).

d) novelty (the level of originality in project goal, processes

and/or output).

e) pace (the criticality and rigidity of the project time

frame).

f) Obeng (1994) provided a simple classification of project

types based on two dimensions - the level of clarity and detail

at the outset of the project about what needs to be done and

how to do it. These dimensions are used to create the following

classification:

i. closed (stakeholders know what to do and how to do it

at the outset).

i. closed (stakeholders know what to do and how to do it

at the outset).

iii. semi-closed (stakeholders are given a reasonable level

of clarity about what needs to be done, although often somewhat

general, but still need to figure out how to do it).

iv. open (stakeholders are unsure of what needs to be done

and unsure of how things will be done when the project is initiated

and in some cases at various points along the way).

Closed conditions are generally associated with low

levels of complexity, uncertainty, technology, novelty and pace. Contemporary conditions have elevated all of the key

differentiating factors resulting in a shift away from closed

conditions toward more semi-closed and open conditions [28].

Measurement of project success has traditionally focused on

what is referred to as the golden triangle – meets the deadline,

within budget and addresses the established scope [29]. This

approach has been criticized for being too narrow [30] especially

when considering the broader impact of key projects like Microsoft

Windows which was considered a significant failure relative to

the original deadlines, budget and scope. Criteria used to measure

project performance has expanded to include the following levels

[27,31]:

a) process (optimal identification, selection,

implementation and management of project processes).

b) project management (meets time, budget, scope

requirements).

c) customer/deliverable (quality, quantity, specifications,

acceptance, use, impact, satisfaction).

d) business success (impact on business goals and

performance).

e) strategic success (impact on market, competitors,

investors and other key stakeholders).

e) strategic success (impact on market, competitors,

investors and other key stakeholders).

g) team impact (extend to which the execution of the

project supports the capacity of project team members to continue

working together in an efficient and effective manner).

The clarification and expansion of performance criteria has

improved the ability to identify the key determinants, mediators

and moderators of project performance, including the contribution

of the personality, management/leadership style and associated

competencies of project managers and participants [32].

Research on the influence of the project management

competencies suggests a contingent relationship and the need

for alignment with project type, conditions and stage [33,34].

In an attempt to categorize the expanding domain of project

management competencies, Shenhar & Div [27] suggest that

project management competencies be organized into 4 groups:

a) traditional/operational excellence (planning and

executing a sequence of project activities to ensure completion of

the project scope on time and within budget).

b) dynamic adaption (management of change within the

project).

c) strategic focus (strategic alignment of the project,

creating a competitive advantage for the organization and adding

value at the strategic level of the organization).

d) inspired leadership (motivating and managing project

team members and other stakeholders to evoke and maintain

their support and commitment to the project, creating project

spirit through supporting vision, values and artifacts) [35].

They suggest that the profile of required project management

competencies depends on the complexity, uncertainty,

technology, pace and novelty of the project. Traditional

(operational excellence) competencies may be both necessary

and sufficient within closed project conditions that are relatively

stable, simple, low tech and do require high levels of novelty.

Although the traditional competencies remain necessary, they

become increasingly insufficient as the complexity, uncertainty,

technology, novelty and pace increase (project conditions become

more open). Increasingly open project conditions requires

the addition and integration of dynamic adaptation, strategic

focus and inspired leadership with the traditional (operational

excellence) competencies.

Although the failure rate of projects remains a concern

[32], research suggests that effective project management is

a contributor to business success in a variety of industries and

sectors [36,37] and that project performance is influenced by the

personality, management/leadership style and competencies of

the project manager [38-42].

Many of the core project manager competencies rely on

higher order cognitive processes which are typically disrupted

by attention related disorders [43,44]. The significant reliance of

traditional (operational excellence) competencies on higher order

processes like impulse inhibition, planning, modeling, prediction,

goal and priority setting, sequencing and problem solving suggests

that operational effectiveness may be particularly impacted by the

disorder. These are also referred to as the process competencies.

The ongoing necessity and foundational nature of traditional

competencies (operational excellence) in spite of growing

insufficiency as project conditions become more open, suggests

that AAD may have an important influence within the nomological

network that determines both project manager, team member and

project performance. A search of multiple databases (medline,

psyc-info, academic source premier, business source premier

etc.) produced no empirical studies on the relationship between

attention related disorders/conditions and project management.

Definition and impact

Belief and disbelief systems satisfy the need for a cognitive

framework that defines situations and provides protection from

threats [45]. Dogmatism is generally defined as a closed belief

system resulting from a rigid attachment to particular beliefs

that are resistant to opposing beliefs. Rokeach [45] suggests that

dogmatism is defensive in nature and encompasses a constellation

of psychoanalytic defenses that help to shield a vulnerable

mind. More recently, Altemeyer [46] defined dogmatism as “an unjustified and unchangeable certainty in one’s beliefs, reflecting

conviction beyond the reach of evidence to the contrary” (p. 201).

Rigid attachment to a particular set of beliefs helps to protect

self-directing processes that are relatively more vulnerable to

disruptive external and internal stimulus [47]. Defensive cognitive

closure, rigid certainty and isolating (compartmentalizing)

contradictory beliefs is a way to protect higher order cognitive

processes from complex external stimulus that may create the

experience of cognitive chaos, confusion, vulnerability and

anxiety. Rigid cognitive structures are also a way to defend against

the disruptive impact of emotions like anxiety, fear or anger

that have reached a level of intensity that disrupts self-directing

cognitive processes.

Developmental psychologists have consistently identified

early psychosocial conditions in the parenting process and

a biological vulnerability for hyper-arousal, environmental

stressors and disrupted socio-culture learning as the distal

causes [47]. Anxiety that arises in childhood and persists through

adolescence and into adulthood will help to rigidify the belief

system as a means of personal defense. Recent research by Brown

[44] identified an association between disrupted functioning of

short-term memory and dogmatism suggesting a link between

rigid (defensive) thinking and adult attention deficit.

Research on the impact of dogmatism on mental health

and general functioning has identified mostly detrimental but

some beneficial effects [48-50]. Research on the occupational

impact of dogmatism has revealed an association with both high

and low performance [51,52]. Dogmatic workers are likely to

struggle in situations that are dynamic, uncertain, and complex,

and require high levels of reflection, flexibility and cooperation

with others [7]. However, a dogmatic thinking style may be useful

when performance supporting cognitive and emotional states

are particularly vulnerable to external and internal stimuli that

may produce disruptive cognitive dissonance [53]. The impact of

dogmatism on health and performance appears to be moderated

by personal vulnerability to disruptive dissonance. For workers

who are prone to confusion and indecision as the complexity and

intensity of external and internal stimulus increases, the benefits

of a dogmatic style may outweigh the costs.

Hypotheses

The proposition guiding this research study is that

dogmatism moderates the negative relationship between AAD

and the operational effectiveness of project managers (referred

to as operational effectiveness). Project managers who use a more

dogmatic orientation toward managing the operational aspects of

a project, especially under closed or semi-closed conditions (low

need for dynamic adaption), may be able to generate a higher

level of cognitive protection from the disorganizing effects of the

disorder.

Employees with operational project management

responsibilities who experience difficulties with getting organized

and started on tasks, concentration, sustaining effort, managing

emotional interference, using short term (working memory)

and accessing learned material, will have greater difficulty

achieving operational competence. They will be less able to

activate and organize the project initiation stage, establish clear

and appropriate project goals, map out and schedule the require

tasks, organize and integrate the tasks into an efficient project

plan, manage project participants and ensure timely completion

of the project within scope and budget. Difficulties with attention

and concentration will undermine the ability to consistently pay

attention to the details of the project plan resulting in inefficient

reexamination. Difficulties with energy and effort will constrain

the consistency and duration of effort needed to ensure timely

completion of critical end-to-end tasks.

Impulsivity and emotional reactivity may be viewed by others

as impatience and a lack of confidence in others which may

constraint the formation of trusting, constructive and supporting

relationships. Disordered adults are often indecisive [54] when

facing conflicting goals and disproportionately attentive to tasks

that are immediately gratifying and of relatively greater personal

interest [13]. This should further constrain operational efficiency

and effectiveness.

H1: Adult attention deficit is negatively associated with the

operational effectiveness of project managers

Disordered project managers may be able to constrain the

level of manifest disorganization, indecision and confusion

associated with the disorder by using a more dogmatic orientation.

This is more likely to be beneficial within closed/semi-closed

project conditions that don’t require high levels of flexibility and

dynamic adaptation. The use of a dogmatic orientation may help

to shield a vulnerable mind from internal and/or external stimuli

that promotes disorganization, indecision and confusion, and/

or constrain the behavioral manifestation of these symptoms

resulting in levels of decisiveness expected from the operational

role of a project manager.

H2: Dogmatism moderates the relationship between adult

attention deficit and the operational effectiveness of project

managers

The subjects were 160 actively employed business graduate

students attending a university in the United States. Subjects

participated in business courses that required them to work in

4 person autonomous project teams. Each team was responsible

for completing a major business project which required the

completion of 4 sub-projects. Each team was required to complete

a strategic planning process and produce a strategic plan based on the 4 traditional elements of strategic planning - external

opportunities and threats plus internal strengths and weaknesses

(SWOT). Each team member was required to manage one part of

the SWOT analysis and the other team members were required to

work for them on that particular sub-project. Each of the 4 subproject

managers (team members) were expected to integrate

their sub-projects into an overall strategic plan and manage the

progress of the overall project. The general operational phases of

project management, related competencies and tools were briefly

reviewed at the beginning of the course.

The project conditions were semi-closed because the project

outcomes (scope and timeline) were specified with a reasonable

level of clarity and detail from the outset but the process of further

defining the outcomes where necessary, and determining the

process for achieving the outcomes, was delegated to the project

managers. The project conditions represent low to medium

complexity, uncertainty, technology, novelty and pace. These

conditions mostly emphasize the need for operational project

management competence.

At the end of the semester each of the team members

completed an assessment of the operational project management

effectiveness of the other team members. Each subject was also

asked to identify someone who knew them well and would be

willing to complete an honest assessment of their behavior.

The identified observers completed an observer version of the

Brown Adult Attention Deficit Scale (BAADS) under conditions of

anonymity. Each of the subjects completed a self-report measure

of dogmatism.

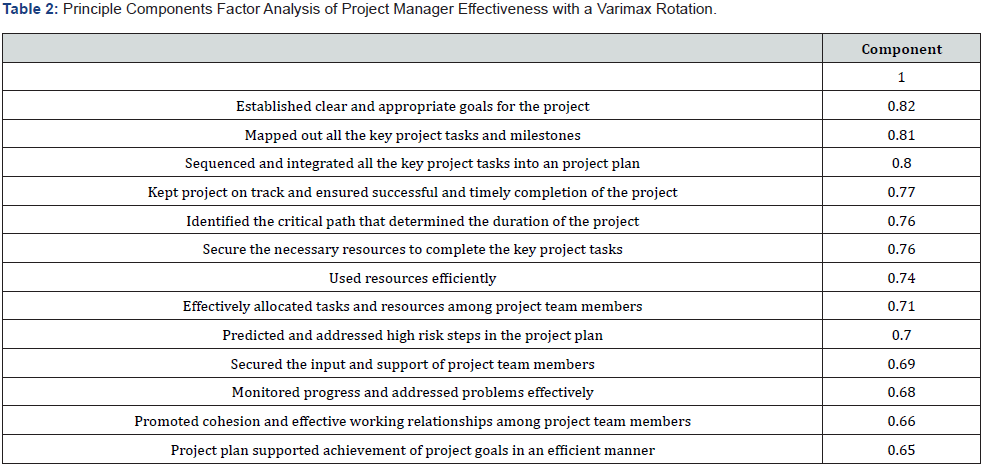

Principle components factor analysis with a varimax rotation

was used to confirm the dimensionality of the project manager

effectiveness measure, and examine the contribution of the

individual items to the factors. Product moment correlations were

used to test all the hypotheses regarding associations between the

measures. Linear regression that included the multiplication of

standardized independent and moderator variables (moderator

variable) was used to test for a significant moderating effect.

Adult attention deficit (ADD)

The Brown (1996) Adult Attention Deficit Scale (BAADS)

contains forty self-report items that measure the five symptom

clusters. Organizing and activating to work (cluster 1) measures

difficulty in getting organized and started on tasks (e.g.,

“experiences excessive difficulty getting started on tasks”).

Sustaining attention and concentration (cluster 2) measures

problems in paying attention and concentrating while performing

tasks (e.g., “listens and tries to pay attention but soon becomes

distracted”). Sustaining Energy and effort (cluster 3) measures

problems in maintaining the required energy and effort while

performing tasks (e.g., “runs out of steam and doesn’t follow

through”). Managing affective interference (cluster 4) measures difficulty with moods, emotional reactivity and sensitivity to

criticism (e.g., “is easily irritated” and “has a short fuse with sudden

outbursts of anger”). Utilizing working memory and accessing

recall (cluster 5) measures forgetfulness in daily routines and

problems with recall of learned material (e.g., “intends to do

things but forgets”). The questions are phrased in third person

singular to support observer ratings (e.g., “” the person being

described is disorganized”). The instrument uses a four-point

behavioral frequency scale (0=never, 1=once a week, 2=twice a

week, 3=almost daily). A total score for AAD was generated by

adding up the scores on all of the questions.

Dogmatism

The new dogmatism scale (DOG) [46,55] was used to measure

dogmatism. The instrument was designed and validated for

use with adults and contains 20 items that measure general

dogmatism. Example items for the scale include the following: “I

am absolutely certain that my ideas about the fundamental issues

in life are correct”; “The things I believe in are so completely true,

I could never doubt them”; and “I have never discovered a system

of beliefs that explains everything to my satisfaction” (reverse

coded). Subjects used a seven-point Likert scale (1=strongly

disagree, 2=disagree, 3=slightly disagree, 4=neutral, 5=slightly

agree, 6=agree, 7=strongly agree) to rate the extent to which

they agreed with each item. Each of the subjects completed the

dogmatism measure and a total score was derived by adding

up the scores on the individual items (some items needed to be

reversed).

Operational project management effectiveness

Items for measuring the operational effectiveness of project

managers were developed after reviewing the core project

management competencies outlined by the International Project

Management Association [56], the Project Management Institute

in the United States (2008) and recent research on the assessment

of project managers [57-60]. There was no well-established

instrument that focused exclusively on measuring the operational

effectiveness of project managers as outlined by [27]. However,

most existing instruments and competency profiles contained

parts that referenced the operational effectiveness component of

project manager performance.

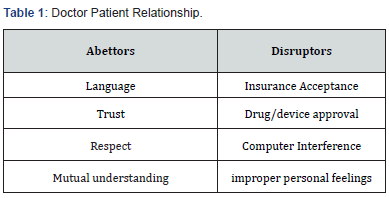

Thirteen items that represent the key operational (traditional/

process) project management responsibilities described by

Shenhar and Dvir [27] were selected and worded in a general

manner that encompassed most project management situations,

including the situation that the subjects were embedded in (Table

1). Example items are “mapped out all the key project tasks and

milestones”, “identified the critical path that determined the

duration of the project” and “secured the input and support of

project team members.” Observers used a seven-point Likert scale

(1=strongly disagree, 2=disagree, 3=slightly disagree, 4=neutral,

5=slightly agree, 6=agree, 7=strongly agree) to rate the extent to

which the project manager demonstrated each competency. Each

project manager was rated by the other three members of the

project team and the scores on each question were averaged and

then added to get a total operational effectiveness score.

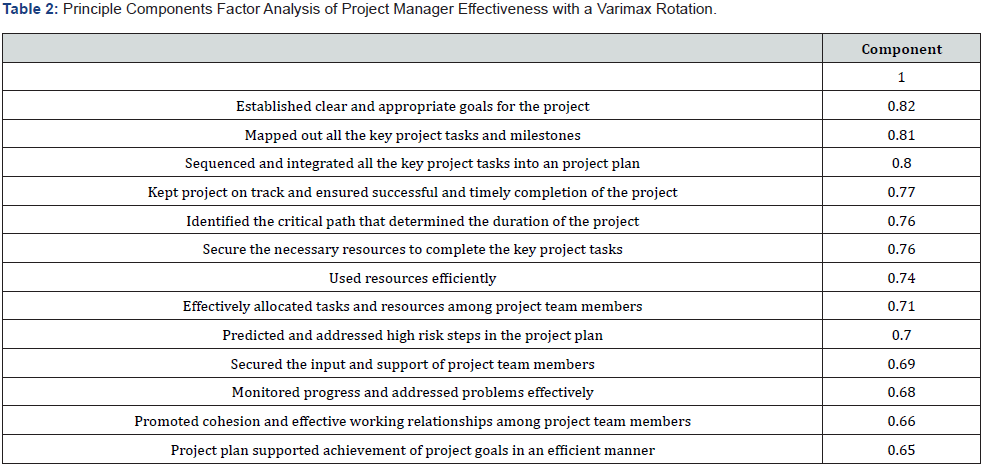

A principle components factor analysis with an orthogonal

rotation (varimax) was conducted to examine the structure of the

project manager effectiveness instrument. The factor analysis for

the project manager effectiveness items produced a single factor

with factor loadings ranging from 0.65 to 0.82 suggesting that

each item is making a meaningful contribution to the measure.

The Cronbach alpha internal reliability coefficient was α = 0.89

and could not be improved by eliminating items. This suggests

that the instrument has good internal reliability, and each item is

making a meaningful contribution (Table 2).

The average intra-class correlations (two-way mixed effects

model with absolute type agreement) among team member

ratings of project manager effectiveness ranged from 0.71 to 0.90

suggesting acceptable inter-rater reliability. Means, standard

deviations and correlations among the variables appear in Table

1. All variable distributions were approximately normal and

demonstrated reasonable variation across their respective scales.

No univariate or bivariate outliers were considered problematic,

and the product moment correlations revealed significant

associations between the variables. The mean, standard deviation

and maximum score for AAD (avg = 39.24, std dev = 18.34, max

score = 104) are not significantly different from the instrument

validation samples and previous samples of subjects taken from

the same university and a similar university in western Canada.

Cronbach alpha internal reliability coefficients ranged from (α

= 0.89) to (α = 0.93) suggesting good internal reliabilities. The

linear regression for testing the moderation effect produced no

problematic residuals (Table 1).

The significance threshold for empirical tests was

set at α =

0.05 (2 tailed). The correlation between AAD and project manager

effectiveness (Hypothesis 1) was statistically significant (r = -0.35, p

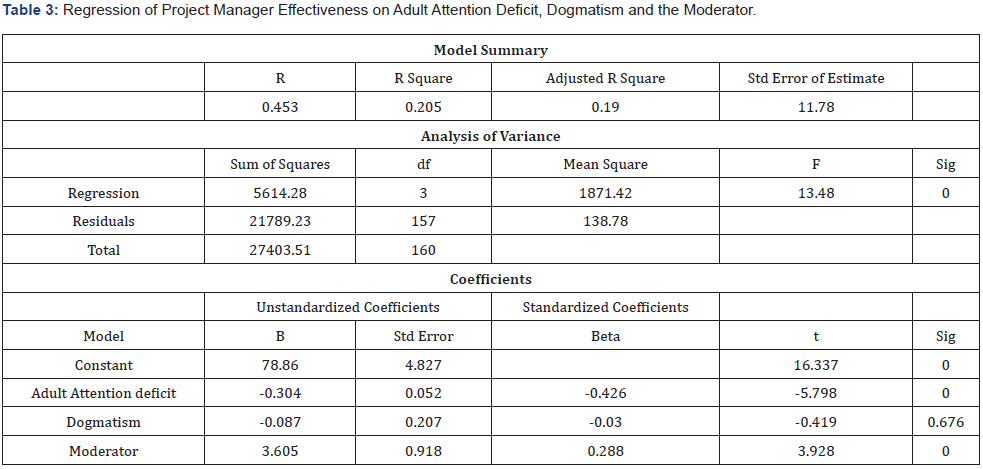

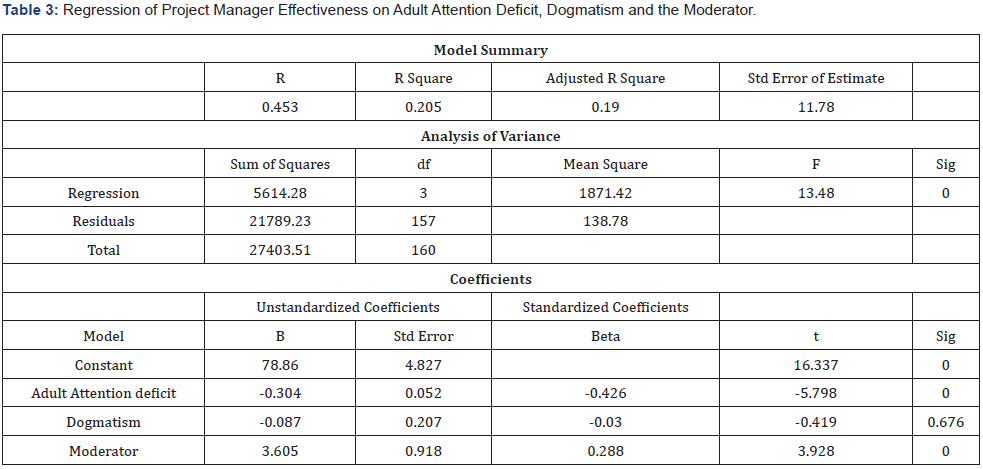

< 0.01). The linear regression of project manager effectiveness

on adult attention deficit, dogmatism and the moderator

(multiplication of the standardized dogmatism and adult attention

deficit variables) produced a statistically significant moderator

effect (β = 0.29 p = 0.000). An examination of the moderator

graph (Figure 1) confirms that the negative relationship between

adult attention deficit and the operational effectiveness of project

managers declines as dogmatism increases (Table 3).

The results suggest that AAD constrained the

operational

(traditional/process) effectiveness of project managers and that the

negative relationship between AAD and operational

effectiveness declines as dogmatism increases. The directionality

of this relationship cannot be confirmed from this research study

and both opposite and bi-directional effects are possible. The

large number of studies confirming the significant contribution of

genetic factors to the manifestation of the disorder [43] provides

general support for the hypothesized direction in this study.

Recent research suggesting that certain contextual conditions like

parental conflict and inconsistent parenting may help manifest

a genetic predisposition or strengthen existing symptoms [61]

suggests that certain project conditions may contribute to AAD.

Organizations wishing to ensure the success of key projects

need to be aware of the influence of adult attention deficit and

dogmatism on project manager effectiveness. The emergence

of more empowered work cultures, tighter deadlines, the need

for creativity/innovation and project-oriented work represents

both an opportunity and challenge for disordered employees.

Disordered employees without the necessary support will

not be able to leverage their strengths and may constrain the

performance of interdependent others.

The protective influence of dogmatism on the execution

of operational project tasks by disordered project managers

suggests the need for conditions, tools and competencies that

protect higher order cognitive resources from disruptive external

and internal stimulus. The provision of project management

training/coaching, project management tools and a workspace

free of unnecessary distractions may be especially important

for project teams containing disordered employees. Although

a dogmatic style may be beneficial under relatively simple and

stable conditions, it is unlikely that a defensive and rigid cognitive

style will support project management effectiveness under

increasingly dynamic and open project conditions. Organizations

need to help disordered project managers and participants find

substitutes for dogmatic thinking processes that possess similar

protective benefits but avoid the related inflexibility and social

challenges associated with being dogmatic. Helping disordered

project managers to better manage anxiety, stress, emotional

disruption, and find an appropriate balance between assertiveness

and collaboration, is likely to play an important role in developing

constructive substitutes for dogmatic thinking.

The increasing availability of effective coaches (life,

organizational, task, peer, manager as coach etc.) [62] offers a

potential substitute for close supervision and a potentially more

accepted and developmental resource for keeping disordered

employees oriented toward successful completion of priority

tasks and projects. Effective organizational coaches could address

a wide range of cognitive, emotional and behavioral deficits,

and protect the employee from the reinforcing cycles of failure

that many disordered employees experience [63]. Establishing

reciprocal peer coaching systems within project teams or

the organization as a whole, that addresses challenges at the

individual and relational level may add considerable mutual value,

especially for disordered employees [64,65]. Coaching processes

that contain the necessary structure and content for supporting disordered employees are needed.

The effective use of project teams represents an opportunity

for distributing the creative benefits associated with the disorder

while managing the deficits. Team members and peer coaches

can help disordered employees to activate, organize, stay on

track, maintain a balance between organizational citizenship

opportunities and priority work tasks, avoid experiences of

failure and manage challenging emotions. They can also help

disordered employees address the pitfalls of rigid thinking and

behavior. In return, team members can benefit from the creativity

that disordered employees may offer. This will require the careful

design of teams to ensure optimal person-role fit and supportive

team development interventions. Team building that educates

team members about the disorder and addresses the social

and task performance challenges while taking advantage of the

benefits is required. Structured collaborative decision-making

processes that provide team members with the opportunity to

optimally locate themselves within the process should improve

person-role fit, avoid the problems of excessive rigidity and ensure

timely decisions. Shared management of projects that partner

disordered project managers with someone who is flexible and

has strong administration and social skills may support both

individual and project effectiveness.

The multi-modal approach to managing the disorder in the

workplace suggests that sustained improvement will depend on

other forms of support like the general education of both managers

and employees, establishing supportive organizational cultures

and climates, appropriate medication and coaching/training

that address key underlying cognitive, emotional and behavior

deficits (e.g. retention training to support effective and efficient

use of short term memory). The provision of employee assistance

programs that provide disordered, potentially disordered and

non-disordered employees with information about the disorder

and opportunities for assessment is an important part of the

constructive management of employee diversity. This will help to

create a more inclusive, supportive and responsive organizational

culture. This will also increase the likelihood of the employee

seeking out other important parts of multimodal treatment,

particularly medicinal support.

Education institutions, like management programs within

universities, need to assist new project managers to recognize and

respond to the symptoms of the disorder in both themselves and

others. Early diagnoses and treatment may help to prevent the

exacerbating cycles of failure that often accompany the condition.

Educating future managers about the condition will help to ensure

that they do not become a contributor to the emergence and

reinforcement of such cycles through ignorance or the inability

to be supportive. Project management training, peer coaching

systems and student team interventions that address the disorder

in a constructive manner will help prepare all future managers

for the challenges of the contemporary workplace. Education and training that improves self-awareness, emotional intelligence,

effective use of working memory and constructive assertiveness

may help substitute for the protective use of dogmatic thinking

styles.

Increasing social, economic and legal pressures to provide

reasonable accommodation for functional but disordered

employees and take appropriate advantage of employee diversity

underscores the general social value of this research.

Future research requires use of samples that are more directly

associated with the workplace. The influence of creativity within

the relationship between AAD and project manager effectiveness

requires further investigation and may reveal beneficial aspects of

the relationship. Measures of project management effectiveness

that include items related to the creative dimensions of a project,

when such dimensions are required, are needed to support this

research. A system for classifying the creative requirements of

projects will help develop the moderating variables needed to

reveal project management situations within which the disorder

may be beneficial. This research supports the general proposition

that the disorder has significant influence within the nomological

network that determines individual, team and organizational

performance.