Oceanography & Fisheries - Juniper Publishers

Abstract

Occurrence of the invasive seagrass Halophila stipulacea is being reported for the first time from the Levantine Mediterranean shores of Israel. The study tries to shed light and discuss the very late appearance of this alien species on the southern coast of Israel as well as predict the consequences of this invasion and the possible future threats that it poses to the underwater sandy habitats and the natural local marine flora and fauna of the region.

Keywords: Alien; Cymodocea nodosa; Halophila stipulacea; Israel; Levantine; Mediterranean

Abbreviations: NIS: Non-Indigenous Species

Introduction

Halophila stipulacea (Forsskål) Ascherson is a dioecious tropical seagrass that, in general, has a Red Sea and western Indian Ocean distribution [1]. This invader species was first observed in the Mediterranean Sea in 1894, floating on the surface of seawater, at Mandraki Harbor, located on the northern shore of Rhodes [2,3]. Later, it was recorded from Greece and its surrounding islands, Egypt, Malta, Cyprus, Lebanon, Italy, Turkey, Albania, Tunisia, Libya, and Syria, and today it is considered one of the 100 worst invasive species in the Mediterranean [4,5]. The fact that it was initially found in harbors, serving small vessels, or in their close vicinity, points to boating, namely, fishing trawlers (dredgers) and maybe also anchors of yachts, as the transportation vector for the introduction of this NIS species. Dredgers that drag nets, in order to catch fish, crabs, and mollusks from the seabed, uproot fragmented shoots of H. stipulacea from its beds. Later, fishermen that clean trawler's nets in harbors and ports, where they anchor, release fragments of this NIS of seagrass into the shallow water. Anchors of boats and yachts can also spread this species, pulling it shoots out of the soft bottom and transporting them to marinas and ports [4].

Fragments that sink in the shallow water and lie on the sandy or muddy bottom start growing in the new sites, attaching themselves to the soft substrate by roots, and new seagrass beds are formed. It was Lipkin [3] who first reviewed the successful introduction of Halophila stipulacea in the Mediterranean and discussed its ecology, impact, and significance. However, although Lipkin, other Israeli researches and divers intensively surveyed ca. 200 kilometers of the Israeli Levant Mediterranean shore, studying Cymodocea nodosa (Ucria) Ascherson, the only native seagrass species found along the Israeli Levantine Mediterranean, and seeking for H. stipulacea, which is very abundant and well known bed forming species (to researchers and divers) on the Red Sea shores of Israel [6], in the 20th century and during the first decade of the 21st century, they did not find any evidence indicating that its range reached the Israeli shore [6].

Current twenty years of seagrasses surveys conducted both in the intertidal and subtidal, up to 30 m depth, along the Levant Mediterranean shore of Israel, indicated that Cymodocea nodosa completely disappeared from the intertidal zone and the shallow subtidal (up to 8 m depth) and was pushed to deeper subtidal sandy habitats, mainly below 18 m depth. Moreover, this species, that used to form beds at the shallow subtidal [6], is now forming rare and very small sporadic patches, in the deep water, which are highly separated from each other. A winter survey that took place in February 2015, after a big storm, revealed the first record of Halophila stipulacea from the southern Levant shore of Israel. Specimens were collected from the drift, cast ashore, at Zikim (31°36'26.2794''N, 34°30'1.8''E) and the shallow water of the marina at Ashkelon (31°40'50.4006''N, 34°33'14.9688''E). These two sites (Figure 1) are located in the southern shore of Israel, near the border with the Gaza Strip.

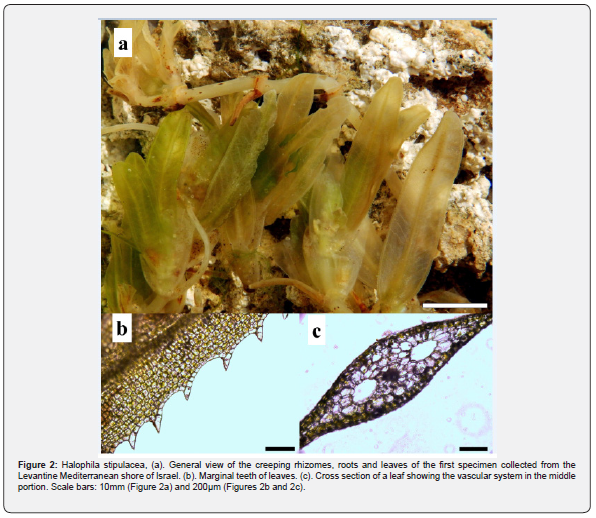

Morphological characteristics of the collected first record specimens (Figure 2a) are in good agreement with the accounts of this species published by Phillips and Meñez [1] and Verlaque et al. [5]. Rhizomes are branched, semi-transparent, 1-2 mm in diameter. Internodes are 1-3 cm long. Each node has one unbranched root, two small semitransparent scales and two leaves. Leaves 2.5-4.5 cm long, 3-7 mm wide; margin dentate (Figure 2b); apex obtuse; base cuneate or gradually decurrent-petiolate. Petiole 0.5-1.5 cm long, sheathing lopsidedly at base. The vascular system is based on a mid (Figure 2c) and two marginal conspicuous veins joined by parallel cross veins ascending from the mid vein at 45-60 degrees. Flowering plants were not observed. Owing to the political situation in the Middle East, the Israeli Navy prevented the entry of fishing trawlers and boats from nearby countries (Egypt, Lebanon, Syria, and Cyprus) into the territorial Mediterranean seawater of Israel, and local trawlers are not allowed to sail out of these waters, for over seventy years.

Therefore, two assumptions explaining the recent invasion of Halophila stipulacea speculate that the source of this alien, in the Israeli Mediterranean, are seagrass beds of this species, reported ca. ninety years ago by Fox [7] from Port Said harbor and the Suez Canal, Egypt. The first scenario points to dredgers and fishing boats, sailing along Sinai Peninsula (see Figure 1), following its return to Egyptian territory, after the peace process between Israel and Egypt ca. 40 years ago, from Port Said, or the Suez Canal, as the vector that introduced and later extended the distribution of H. stipulacea northward along the Mediterranean cost of Sinai till it reached the small harbor at El Arish, located by the border with Gaza Strip. This new population probably spread naturally to the Gaza Strip and later penetrated the southern shores of Israel through shoots forming beds that grew northward or fragments and seeds carried by the natural marine northern currents.

According to the second assumption, the dispersal units produced in H. stipulacea bed located at Port Said or the canal reached Sinai and the Israeli coast naturally through the currents. However, this scenario is less logical because Lipkin, who surveyed the Mediterranean shore of Sinai east of Port Saïd in the sixties and early seventies of the 20th century, before the peace process, did not find any evidence indicating the existence of H. stipulacea in this region [6]. It is more likely that the penetration and invasion of Halophila stipulacea into the southern shores of Israel occurred in the past few years since the beginning of the new Millennium. Moreover, it is quite possible that specimens collected from Ashkelon (see Figure 1) had reached the local marina through the only fishing trawler that sails in the area. Interviewing of the captain of this dredger revealed that the boat drags its nets, on the mix of muddy and sandy bottom of the sea, at the range between the marine border with the Gaza Strip at south Zikim beach and the northern shores of Ashkelon. Furthermore, in Zikim, they drag the nets at ca. 30 meters depth, 5.5 km offshore.

Although fine numbers of fragments of H. stipulacea were found drifted to shore, along ca. 4 km of shore at Zikim, snorkeling along the beach revealed no beds of any seagrass at a depth between 0-8 meters. Thus, specimens that were washed ashore may have come from the deeper subtidal and the littoral where this fishing trawler drags its nest. In general, Cymodocea nodosa, the endemic Mediterranean species, is adapted to an annual gradient of seawater temperatures that characterize temperate seas. It is found growing mainly on sandy bottoms in the shallow subtidal along the Mediterranean coast but also in the north-west Atlantic shores of Africa and the Canary Islands [8]. Due to global warming, seawater temperatures increased dramatically in the last decade, especially in the shallow subtidal of the Levant Mediterranean shore of Israel, and the sea has acquired tropical characteristics [9]. This tropical character of the sea has probably pushed C. nodosa into the deep subtidal, where the annual changes of temperature are less drastic, and simultaneously caused its disappearance from the intertidal and the shallow subtidal.

Because Halophila stipulacea originated from the tropical Red Sea, high sea-surface water temperatures in the Levant are favorable for its growth and promote its establishment, giving it advantages over C. nodosa. Hence, the invasion of H. stipulacea into the subtidal poses a serious threat to the remaining populations of C. nodosa that are pushed into the deep subtidal. Former studies of the ecology of H. stipulacea in the Mediterranean revealed that this is not a finicky species. On the contrary, it shows extraordinary ecological flexibility, growing at a depth between 0-147 m and having extremely high shoot density (especially when beds are located in the shallow waters) compared to C. nodosa [3]. The leaf area and biomass were also found to be high [4]. There are 22 dredgers sailing and fishing along the Levant Mediterranean shore of Israel [10], and it is expected that H. stipulacea will spread its distribution northward very quickly to local harbors, marinas and ports through these boats and the local northward currents.

Considering the high invasion rates of NIS in the Levant Mediterranean shore of Israel, Halophila stipulacea may also play an important role in the process and the success of other alien invasions, giving them a familiar habitat, as was the case with the invasion of the NIS red seaweed Chondria pygmaea Garbary & Vandermeulen or the NIS of mollusk Syphonota geographica Adams & Reeve, which has a dietary dependency on this seagrass [4]. These examples indicate that the initial invasion of an exotic pest such as H. stipulacea might have paved the way for the subsequent invasion of trophic specialists that take advantage of niche opportunities, and some of these invaders might also have negative effects on the local Mediterranean flora and fauna [4]. Recent study of fungal parasite that infest H. stipulacea indicates that the parasite, initially found and described from the Red Sea, also infest beds of introduced H. stipulacea in the Mediterranean [11]. The occurrence of this fungus in the Mediterranean may also poses threat to the local and endemic seagrasses including Cymodocea nodosa.

Conclusion

The political conflict in the Middle East is probably the reason for the very late introduction of the non-indigenous species Halophila stipulacea on the coast of Israel. This common alien seagrass species was reported from all the Levantine Mediterranean shore a long time ago, but this study presents its first record from the Israeli Levantine waters. The fact that this seagrass was found specifically on the southern shores, by the border with the Gaza Strip, and not in the systematically explored central and northern coasts, indicates that it probably originated from the north coast of Sinai Peninsula. The penetration of this opportunistic NIS on the subtidal sandy habitat might push the remaining population of the local endemic seagrass Cymodocea nodosa, and other organisms connected to this ecosystem, on the brink of extinction.

To Know more about Oceanography & Fisheries

Click here: https://juniperpublishers.com/ofoaj/index.php

Click here: https://juniperpublishers.com/index.php

No comments:

Post a Comment