Archaeology & Anthropology - Juniper Publishers

Abstract

Within the concept of Public Archeology, this article aims to excel on the preservation and safeguarding of the memory of the resistance movements against the military regime as public art and Brazilian historical heritage, highlighting the monument to the army captain and guerrilla Carlos Lamarca (1937-1971), located in Vale do Ribeira, which had been removed from the site with the justification of apology to crime. Lamarca led the Revolutionary Popular Vanguard (VPR) in the 1970s and played a steadfast role against the military regime established in the country between the years 1964 and 1985.

Keywords: Carlos Lamarca; Heritage; Public Archeology; Memory; Safeguard

Introduction

There is no future without a past, for which Archeology contributes. Over the years, Archeology has been the subject of discussion about its importance for safeguarding and enhancing cultural, material and immaterial goods. Due to its wide scope, working on heritage preservation issues requires facing barriers; know concepts and legislation relevant to safeguarding heritage; adapt to the concepts; recognize and respect the differences that social groups attribute to their experiences; among other sensitive issues. During this period, the Prehistory Commission established in 1952 by the intellectual and humanist Paulo Duarte (1899-1984), in order to protect archaeological sites, passed Law 3924/61, in 1961. The law deals with the “Archaeological and prehistoric monuments” and establishes the protection of both by the State. According to the Brazilian historian and archaeologist Pedro Paulo Funari, “to this day it is still the only explicit federal law on the protection of archaeological heritage”.

In this process, Luiz de Castro Faria (1913-2004), anthropologist, archeologist, professor, librarian and Brazilian museologist, who contributed a lot to the debates about Law 3924/61, known as archeology law for having provisions on archaeological monuments, stands out of Brazil. Castro Faria left an immeasurable contribution to safeguarding the archaeological cultural heritage. During the military period (1964-1985), Archeology suffered strong pressure with authoritarian tendencies. From 1985 onwards, democracy opened up to the development of a series of new activities with the archaeological heritage as an example, published books, academic articles and constant meetings on the management of cultural heritage. “Several states have introduced legislation to protect archaeological sites and instituted records of monuments and archaeological collections” [1].

Archaeological research has been carried out across the country thanks to the publication of heritage laws. In the last few years, Brazilian archeology is no longer restricted to the academy and starts to include an agenda in Public Archeology (the result of transformations in the midst of societies and Archeology science). The term Public Archeology was first mentioned in 1972 in the work of Charles McGimsey III, linked to the management of cultural heritage and differentiating itself from exclusively academic research. This recent field, understood as a discipline aimed at interaction and sharing with society - and that understands the public not only as local groups, ethnic communities and students, but also the society in general that reads, interacts and reflects; Developing itself as a field of interdisciplinary studies, Public Archeology has as one of its main objectives the reflection on methods, practices, values, meanings and how archaeological works would be disseminated, thus providing dialogues and debates regarding the symbologies and of representations through material culture. That is, works in the field of Public Archeology are linked to political and social issues, promoting awareness in society in relation to safeguarding heritage and corroborating society’s interest in scientific, economic, artistic and educational aspects. That said, this article aims to guide your discussions in the context of the defense of the archaeological, historical, artistic, cultural heritage and mainly the preservation of the memory of the movements of resistance to the military regime in the country, taking as a framework, the bust of Carlos Lamarca, opened in 2012 at the Núcleo Capelinha museum of the Rio Turvo State Park (PERT), municipality of Cajati, Vale do Ribeira.

The bust of Lamarca was a project of the Park council, formed by the community and members of the government. Arbitrarily removed from his place with a photo panel that told the story of the guerrillas and the repression of the lead years, he was taken to the capital in August 2017. This act was derived from an environmental briefcase (action by the secretary of the environment of the state of São Paulo, Ricardo Salles, today Minister of the Environment), which directly interfered in the local history, attentive to democratic freedoms and violating the right to collective memory and regional identity. Before focusing on issues related to the removal of the monument to Carlos Lamarca and the clashes to safeguard the archaeological heritage, as well as our identity and memory; it is relevant to talk about the figure of Lamarca and his importance for the history of Brazil. After 49 years of his death, Lamarca played a very important role in the fight against Brazilian dictatorship. According to historian Wilma Antunes Maciel, “Lamarca is both the individual, a hated ex-soldier, but also the organization itself and what it represents in opposition to the regime.” Condemned as a traitor and deserter, he led several urban guerrilla actions, ordered a guerrilla focus in the Ribeira Valley and led the kidnapping of the Swiss ambassador to Rio de Janeiro in the 1970s, in exchange for the release of 70 political prisoners. Lamarca was killed on September 17, 1971 in an operation organized by the military in the interior of Bahia, thus becoming a relevant part of the country’s history.

Carlos Lamarca and Its Trajectory

“We lose the right to die until death is an example.”

(Carlos Lamarca)

Carlos Lamarca was born in 1937 in the city of Rio de Janeiro. Son of a shoemaker and a housewife, he studied from an early age aspiring to overcome the needs of his humble family. In the 1950s, he opted for a military career, after graduating in the South in 1954, Lamarca joined Agulhas Negras in Resende, Rio de Janeiro in 1958. He married his childhood friend Maria Pavan. His predilection for political readings begins through the press organ of the PCB (Partido Comunista Brasileiro), The Workers’ Voice, whose party cell was responsible for infiltrating “pamphlets and documents left under its sheet” [2]. Lamarca was never outside the party, but he sympathized with communist ideals. Appointed to serve in São Paulo as an aspiring officer, he joined the 4th Infantry Regiment in Quitaúna in Osasco, in 1960.

Lamarca is standing out in the military field, in 1962 he is sent to the UN (United Nations) peacekeeping mission, in the Suez Canal, located in the Middle East. The poverty of the Palestinian people will make them reflect on the issues of the Brazilian reality: At Suez he learns new things. AMarina and her friends commented that the reality of the Arab people was much more cruel. That the Arabs were hungry. That they suffered a lot, just like the Brazilians, and if I were to fight, to be fair, I would have to go to their side. And it would pass if there was combat, he said. It was there - he said one day - “that I became more aware of poverty” [2].

After his return, he served in the Army Battalion of Porto Alegre. Soon he asks for a transfer to the city of Osasco, metropolitan region of São Paulo, where he meets his former companion, sergeant Darcy Rodrigues, who worked in the regiment as an agitator, proposing the formation of a study group concerned with the political issue and with the national situation. In the years 1969-1970 (period of the civil-military dictatorship), Carlos Lamarca acts at the head of the VPR (Popular Revolutionary Vanguard), leading the organization’s command and leading the armed resistance to the dictatorship within a program of liberating national revolution towards socialism. Coming from dissidents, the VPR intended to fight against the dictatorship based on cadres from the lower ranks of the army, noncommissioned officers, workers and members of the student movement. Military austerity culminated in the formation of connected cadres under Lamarca’s leadership and reported on his career as a captain. His status as a soldier and officer will succumb after the assault on the Quitaúna Barracks in January 1969. This joint action was attended by Darcy Rodrigues, Carlos Roberto Zanirato and José Mariane, which resulted in the flight and expropriation of weapons and ammunition.

The majority of the VPR activists fall underground and as deserters assume the condition of revolutionaries, leading the beginning of insubordination as subversives, with Lamarca at the head of the VPR command. Abandoning his career as an army officer, Carlos Lamarca, to dedicate himself entirely to fighting the dictatorship and the liberating national revolution, postulated by the VPR in its program against the civilian military regime, assumes the condition of revolutionary. For the army this will be a betrayal of lesa homeland, unforgivable, however, to the left this attitude invokes a heroic act [3]. Lamarca appears as a former captain and guerrilla, the antinomism of the figure of the hero / traitor within the political imagination creates ambivalent forces. The choice for desertion conferred himself the title of dissident and traitor to the country. And in this context, as a rebel soldier, who begins his saga at the head of the VPR command, he is invited by guerrilla Carlos Marighella (1911-1969,) to head the armed groups of his organization (ANL- Ação Libertadora Nacional). Lamarca refuses the proposal. After the assault of Quitaúna, one of the decisive actions for the acquisition of funds, the VPR is converted into the VAR de Palmares (Vanguarda Armada Revolucionária de Palmares), in a merger with Colina (National Liberation Command). With ammunition and weapons, they take action initiatives, including the one known as Noite de São Bartolomeu2 and the famous kidnapping of the Swiss ambassador Giovanni Bucher.

Given the application of such actions, the circumstance was to set up a strategy in the countryside, through the difficulty of sustaining the struggle in the city and circumscribing the territory in which a guerrilla school would be implanted, with the purpose of training the city’s combatants. The decision to move city officials to the countryside was made in an unexpected way, even though guerrillas Carlos Lamarca and Yoshitane Fujimori (1944-1970) had already examined the location in which they were going to settle for training.

The driver from Lamarca, Joaquim dos Santos (Monteiro), responsible for logistics, details the events that led them to Vale do Ribeira: Lamarca’s need to go to Vale do Ribeira was an emergency, it wasn’t because we had prepared it, we didn’t even expect it to go to Vale do Ribeira, there was no question of that. We had everything planned to go to Goiás, and we already had all the equipment purchased, we had already gone to the farm, everything was settled for the farm we were going to, not even Lamarca knew where it was. Who was going, who was in charge of doing all this and had chosen the area was Quartim de Moraes, a professor, one of the leaders of the VPR. The greatest leader was Onofre Pinto. Quartim gives up and he I knew about the area in Goiás with about three days left for us to start traveling there, to start transporting people there, at the end of 69 and beginning of 70, and then Quartim comes to me and says: - Look, Monteiro, I will need do me a favor, I’ll need you, I wanted you to lend your documents so I can get a passport because I won’t be able to go there to Goiás, I can’t stay away from my family you know, I had to send everything abroad, they are in Italy and I will not be able to go to Goiás. Then I said: - I am without my documents here, I cannot, so let’s do the following, in the afternoon we will arrange a meeting and then I will give you my documents [...] [3,4].

After the withdrawal of the Quartim leader, a logistical problem for VPR is established and through this unforeseen Monteiro continues: [...] I tried to pretend that nothing was happening for him not to notice, then in the afternoon we go there and pick him up and take him to the device. You will have to explain, it is going crazy, after all the work, all the assembly that we did the boy will, all of that, now you will retreat, retreat under these conditions! Ai will give a damn cake, he just won’t die because Lamarca, Lamarca himself was a very good person and easy to deal with, let’s try to make the gene solve it in another way, then they get him, keep him prisoner in a device and they will fix it later, take him out of Brazil and send him to Italy, he was the son of an Italian and had Italian citizenship, they couldn’t repatriate him here so it was guaranteed that he wouldn’t come back, so he wouldn’t be able to, no I could be here, I couldn’t be suspicious, otherwise he would end up being arrested, he was burned, he was wanted, his name on the “wanted” signs, and at that time they put everyone’s picture, and flooded the entire country. They didn’t have mine, they didn’t have anything they knew about me, I was a rare case, I was from 64 until the day I was arrested and they had no knowledge, nothing about me, they didn’t know my name , they didn’t know who my relatives were, what profession I had, it was the only one I didn’t know, nobody could go more than three or four months without being discovered, I was the only one who had six years and nobody knew anything. So, as a result, then we had to change the hurry, then at a meeting of the command of the rapid VPR, which will decide what we would not decide, this meeting was held in São Paulo. The one in Vale do Ribeira was made in Peruíbe, The Registry Operation3 mobilized the Armed Forces to hunt down the guerrillas led by Lamarca. In this context, under Maciel’s prism, this image of “Captain Lamarca” is constructed, a synonym of betrayal that sustains the feeling of rejection. Lamarca used his skills for the revolutionary cause, known for his discipline, integrity and aim, he skillfully mastered techniques, the handling of weapons and ammunition. Lamarca’s actions on the left did not raise suspicion within the barracks, because, in addition to political participation, he was impeccable with regard to military obligations, being an officer admired by both superiors and subordinates. Shooting champion, his unit hardly missed a competition. For the good relationship and humane treatment for the soldiers, everyone wanted to be under his command [5].

In this way, the command of the VPR with the purpose of forming a revolutionary embryo in the countryside, developed a group of resistance to the military dictatorship, whose aim was to implant a liberating and socialist revolution. Equated with the massive propaganda of defamation against the guerrillas carried out by the Armed Forces, Captain Lamarca and his guerrillas left a strong positive feature in the popular imagination and in the collective memory of the populations of Vale do Ribeira. Aspects of the guerrillas’ respect, admiration, encouragement and solidarity are preserved in the memory of the local rural population, which distinguishes a very different line from the one the army used to pursue them during the anti-guerrilla operation.

Recent reports, according to Monteiro when he will return to Ribeira with Marcelo Rubens Paiva and Pedro Bial in 1996 to launch the book Não És Tu, Brasil and a documentary-vetoed by the army according to Monteiro-, says of the relationship of the residents of the Valley with the guerrillas , that they were very polite and when they kept in contact with farmers they asked to remove bunches of bananas or other food, and when they didn’t ask to buy. They were seen as saints, very good people. Unlike the army and its soldiers and officers who stole chickens and pigs, mistreated simple and humble people, raped young peasants and, according to a report by a resident of Eldorado, had a son murdered [3,4].

As for the organs of the dictatorship in the lead years, Lamarca was seen not only as a traitor, but also as a bandit, resulting in this duality on the memory of the guerrillas, where some reproduce their condition as terrorists and others describe their attitudes as heroic.

In the memory of Luís Carlos, a resident of the Abaitinga neighborhood, located in the municipality of São Miguel Arcanjo (city where the guerrillas went), the following is a reminder: [...] The only thing they said to the people is that he was a defector captain in the army, a terrorist, who killed a lot of people, helped a lot of people, his intention was not to help anyone, who trained street kids coming from São Paulo to steal, and who needed to get them, they couldn’t leave this loose man [3,4]. On the other hand, Darcy Rodrigues, who had been arrested on the run, reports in Antônio Pedroso Júnior’s book: Sergeant Darcy, Lieutenant of Lamarca, the following considerations based on the flight effect on local populations and their relationship with guerrillas: The small group continued to make a run for it, making contact with the peasants of the region in order to obtain food, impressing themselves with the way it was received most of the time. Many of the peasants who collaborated with the guerrillas were tortured and killed by the army [6].

The army campaign had more than 20,000 men from the three armed forces, federal agents and civilians who invested in this defamation campaign against the guerrillas. This all took place in the context of the moment of unraveling and escape in the borders of the municipalities of Sete Barras and São Miguel Arcanjo between Vale do Ribeira and Serra do Paranapiacaba. The breach of the army barrier in the Abaitinga neighborhood in São Miguel Arcanjo, added to the execution of Lieutenant Alberto Mendes Júnior and the ambush of a water truck under the command of Sergeant Koji Kondo, enabled the guerrillas to finally overcome Operation Registro. Its consequences and outcome were cited by Captain Carlos Lamarca himself: We decided to establish contacts with the peasants and started to receive their support. We were surprised by the speed of this support, which they immediately offered us. We did not deceive them, we were frank with them and we were impressed with the ability they showed to understand us. We do not want to give some examples here so as not to compromise entire peasant families, a young peasant couple was murdered by the army. She was pregnant. The peasant must have been tortured because he did not reveal the place where we should have an appointment with him. The repression went to the place, its men disguised as peasants. But we discovered the ruse by the way they responded to our greeting. We immediately raised the alarm. Days later we came, namely, in the city of São Miguel Arcanjo, that the scare was so great that the entire oppressive troop threw themselves to the ground, two of them tore their arms. A sergeant wounded his face on a tree branch. The Public Force soldiers themselves commented on these facts [2].

That said, we can verify a substantial distortion as reports of torture, rape and deaths are recurrent and give us evidence to confront the profile of terrorist and subversive, propagated by the army to Carlos Lamarca and the guerrillas. Historian Jefferson Gomes Nogueira discusses these notes when analyzing the role of the press in the construction of Lamarca’s political imaginary:

Seeking to break with the love and hate relationships that permeate our imagination when we deal with analyzes of that period, we started from the assumption that the mainstream press, during the military regime, contributed to the production of Carlos Lamarca’s image, positioning him as a hero, time as a traitor. In this process of building the image of Carlos Lamarca during the armed struggle in the military regime, the role of the press was fundamental in the selection of the elements that made Lamarca “inhabit” in the political imagination between two myths: that of a liberating hero and the subversive terrorist bandit; in short, a threat to the current social order (NOGUEIRA, 2008, p. 3, 4). Between the erroneous narratives created by the army and the popular imagination that fall on the figure of Captain Lamarca, there are countless attempts to erase the image of the guerrilla with that of his comrades. For example, we have the case of removing the bust of Lamarca from its pedestal (the central object of analysis of our article, which will be presented below).

The Bust of Carlos Lamarca as Public Art and Archaeological Heritage

The monument is everything that can evoke the past, perpetuate the memory [...]”

(Le Goff)

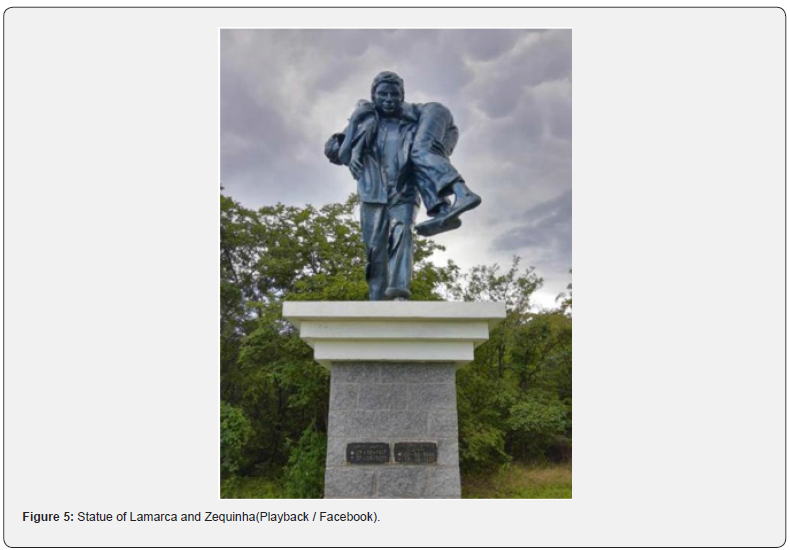

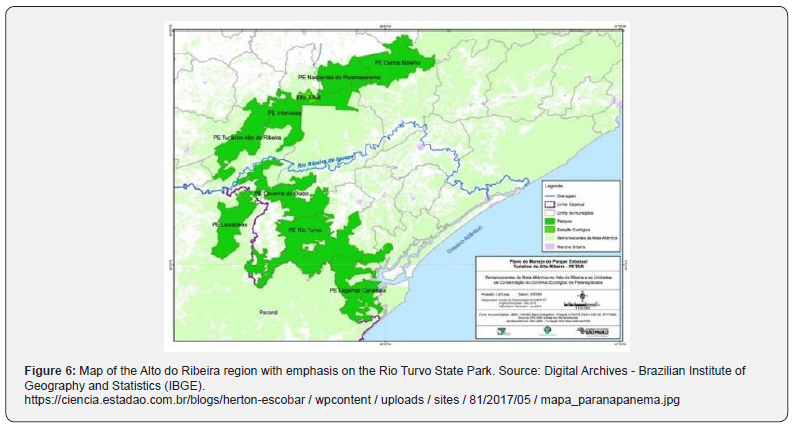

Carlos Lamarca and other guerrillas (all members of the VPR), carried out guerrilla training in the middle of the Atlantic Forest, departing from the Capelinha site, where Rio Turvo State Park is located today (in Cajati, Vale do Ribeira). The guerrillas passed among the trails that covered the municipalities of Jacupiranga, Registro, Eldorado, Cajati and Sete Barras, in a break with the strategic siege of the army. Three monuments symbolize the collective memory crystallized in the figure of Captain Lamarca as a representation of resistance to the lead years: the statue of Lamarca built in 2007 together with the “Captain Carlos Lamarca” square, in the town of Pintada, municipality of Ipupiara, in Bahia; the bust of Carlos Lamarca opened in 2012 in Cajati, Vale do Ribeira and the sanctuary of the martyrs, opened in 2013 (located in the district of Ipeberim - 12km from the municipality of Ipupiara), where you can also find a statue of Lamarca and Zequinha Barreto that symbolizes the last moments of the guerrillas, where Zequinha carries the captain in his arms(Figures 1-5).

All these monuments considered as public art are also Brazilian archaeological heritage. In drawing a comparative brief, we have, on the one hand, the preservation of archaeological heritage in the region of Bahia, in contrast to the other that had been violated arbitrarily in the interior of São Paulo. Made at different times and regions, they all fall within the context of the armed struggle in Brazil and represent the struggle for democratic freedoms, even though this has cost the appeal of the revolutionary route.

According to the definition of the Charter for the Protection and Management of Archaeological Heritage published in 1990 by the International Committee for the Management of Archaeological Heritage (ICAHM - ICOMOS), “the archaeological heritage is highlighted as composed of material heritage that can be read or analyzed by Archeology.” That said, we will focus our discussions on the bust of Carlos Lamarca opened in 2012 in front of the CET (Thematic Exhibition Center), located in PERT (Parque do Rio Turvo)4 in Cajati, in the interior of São Paulo.

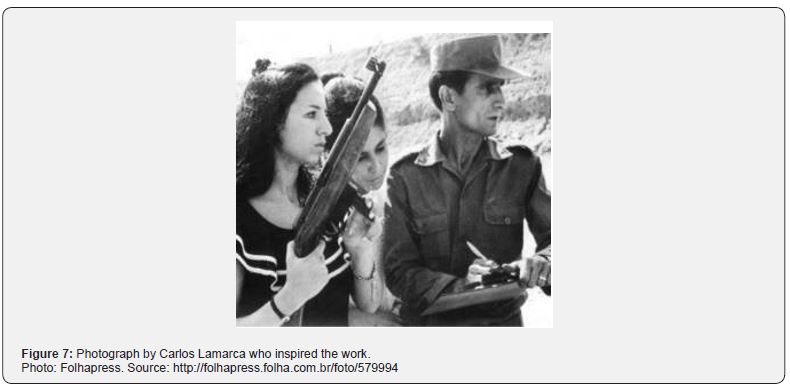

PERT maintains a very close relationship with local communities, currently several groups of traditional populations, such as quilombolas, fishermen and caboclos, who lived in the region before the creation of the unit currently reside in its surroundings. The Park is divided into three nuclei: Capelinha, Serra do Cadeado and Cedro; where they offer visitors ecotourism activities, sheltering an important archaeological site (where a fossil of about 9,000 years old was found, considered the oldest record of human occupation within the State of São Paulo)5; trails; waterfalls; caves and sambaquis. Another attraction that Núcleo da Capelinha has is the passage of Carlos Lamarca and his guerrillas of the Popular Revolutionary Vanguard (VPR) in 1970, during the escape from the dictatorship; the cave and the Lamarca trail connect history and nature. In addition, the Núcleo da Capelinha has a Thematic Exhibition Center (CET), which consists of a museum (Museu da Capelinha). Several themes are treated and exposed at the CET: fauna and flora, the formation of caves, the history of Lamarca, among others (Figure 6). The bust of Lamarca was commissioned by the researcher and park manager Ocimar Bin. The project of the work was carried out by the Cajati journalist Luiz dos Passos and sculpted by the plastic artist Anderson Carvalho. Made of iron, cement, gravel and covered with tar, the work weighed approximately 40 kilos, taking 15 days to be finished, however, it was not completely finished according to its creators6. On the opening day, some of the former guerrilla members went to participate in the official photos, such as sergeants Darcy Rodrigues and José de Araújo Nóbrega, among others who joined Lamarca for training in the region. According to Passos, the bust of Captain Lamarca was inspired by a photograph found on the internet. The photo dates from 1968 when Lamarca was in the army and served as a shooting instructor for Banco Bradesco employees (Figure 7).

In August 2017, the statue of Lamarca is removed from its pedestal along with a panel of photographs and information about the guerrillas, from the Thematic Exhibition Center (CET). The order to remove the bust and the panel was given by the State Secretary for the Environment of São Paulo and current Minister of the Environment, Ricardo Salles7 Rafael Leonard Campolim de Moraes (responsible for the management of Alto Paranapanema of Fundação Florestal, which covers the Rio Turvo State Park and other units). THE bust removal was carried out (without the knowledge of the population) by park and city hall officials in Cajati. The piece was reportedly taken to the city of Registro by the environmental police, and may even leave the country. The argument for withdrawal was that of apology for crime; according to reports8 under condition of anonymity of the unit’s employees to Salles stated that the material exposed was “proselytizing communism” and that “the park is planting communism in the hearts of the children” - the secretary reportedly made these statements to the park’s employees and questioned by the report about this gesture being a prejudice to the historical and cultural heritage, Salles answered through his press office, confusing the name of Carlos Lamarca with that of Carlos Marighella (1911- 1969), another guerrilla belonging to the Aliança Libertadora Nacional (ALN) group .

Narrating facts is one thing. Raising busts with public money and in a public park is quite different. Marighella [sic] was a guerrilla, deserter and responsible for the deaths of countless people. The presence of this bust on the site is unacceptable9 (SALLES, 2017). A little over an hour after sending the secretary’s reply, the Environment Secretariat asked to correct the mistake with the change of names. In addition to the statement by Claudia Lamarca (daughter of the captain), deputy Luiz Turco filed a motion of repudiation in the state Legislative Assembly in August 2017 and deputy Carlos Gianazzi filed a lawsuit in the State Public Ministry for administrative impropriety and dilapidation of property public.

After three years, Salle remains unpunished. There is no information on where the bust is kept, the Forestry Foundation says it is investigating the case. The Public Ministry ordered the civil police of Cajati to open an investigation against Salles for a crime against cultural heritage. Chief Tedi Wilson de Andrade ordered that a precatory letter be sent to the civil police of São Paulo so that the former secretary could be heard in the city where he lives and a request to increase the deadline for the conclusion of the investigation was requested to the Justice. Salles becomes defendant, according to the complaint of the MP accepted in court, he had no authority to have the bust and panels removed, as the installation of the pieces had been decided and authorized by the park management council10 (Figure 8).

In addition, as the bust was carried out with public funds, by ordering the work to be removed, the then minister would have caused damage to public assets. At the time, the work cost 614 thousand reais. The bust was fixed in an outside area of the park, city officials had to use a jackhammer to remove it, which damaged the work (Figure 9). In a more recent statement by Salles to justify his decision to the Public Ministry, published in the newspaper The state of Sao Paulo in January 2018, he points out that he has already provided the necessary information and that he expects the investigation to be closed:

An environmental compensation feature was not designed to put a bust in a park, as they did there. Even more than one person who was a criminal, regardless of the ideological side. It would be the same as a community like Rocinha, in Rio, to use public money to make a statue of Fernandinho Beira-Mar. It would be using public money inappropriately. Even though I am no longer the secretary, I still think that it is not the best thing to have a bust of Lamarca in a public park11 (SALLES, 2018).

Carlos Lamarca is part of the history of Cajati, Vale do Ribeira and Brazil; regardless of the individual’s political position, it does not justify the act of removing this work or any other. The removal of the bust was a disrespect to the population, an attempt to want to erase their history and the presence of guerrillas in the region. Historical responsibility within a dynamic that transposes national identity and its preservation goes beyond policies aimed at safeguarding and sealing official symbols. In the case of authoritarian governments and dictatorships, as well as the suppression of troubled periods of repression and attack on human rights, it is essential to point out the importance of recognizing them with the same responsibility with which the monuments to those considered to be national heroes are preserved.

In this regard, we can quote the work of the historian Deborah Neves: The persistence of the past: heritage and memorials of the dictatorship in São Paulo and Buenos Aires, as a relevant source of aid for the preservation of the memory of the movements of resistance to the military regime (1964-1985). In this work, in addition to Buenos Aires, the author breaks down the cultural assets listed in São Paulo related to the period of the military dictatorship, such as the former DOPS (Department of Political and Social Order)12 and Arco Tiradentes13.

Relativizing the listed assets, such as the Arco Tiradentes and the old DOPS, with the monument in memory of the passage of the guerrilla in Cajati, crystallized in the bust of Carlos Lamarca, consists of emphasizing the importance of the historical, artistic and archaeological heritage of already-listed assets, pointing out that this in question, violated by a portfolio that does not correspond to CONDEPHAAT, has the duty to be safeguarded by public bodies. Even though the bust of Lamarca is not a listed asset, it solidifies the collective memory of the locality, based on the passage of those who fought against the military civil dictatorship.

From Neves’ perspective, in relation to heritage, attempts to conceal and demolish resistance movements explain, on the one hand, the dynamics of public spaces that are altered, mutilated, subtracted in different locations in the country. To the author, the preservation of the memory of the movements of resistance to the military regime is essential.

In this same concealment bias, With the return of democracy, the victims’ relatives and human rights organizations made their demands heard about the excesses committed in dictatorships. The military tried to hide the evidence of their crimes. In this way, they dismantled clandestine detention centers, kept the fate of the bodies secret and destroyed documents about their illegal operations (among others). Despite the testimonies of the survivors, several aspects of the repression remained unknown. It was in this need that archeology started to get involved in the investigations [4,7,8].

In this regard, the urban landscape and artistic manifestations inserted in public areas provide the researcher with elements capable of awakening reflection on the representations of historical memories and identities created in the city space. The recognition of a heritage, implies perceptions of social dynamics and struggles for the preservation of our identity and memory. Our memory can be revived by means of remarkable sensations, odors, sounds, flavors and different forms of visual representations of the urban environment. Socially constructed memory appears to be related to memories associated with monuments and particular places in the city; the observation of artistic manifestations placed in the public space is capable of providing valuable evidence regarding the ways of thinking about city history, among other issues, allowing passersby to interpret (in the symbolic or cognitive field), memories, images and stories of the city. In short, the conceptual assumptions that make up public art are based on the relationships that it is capable of establishing with the space in which it is inserted and with the individual that inhabits the city [9-12].

The habit of filling the urban space with sculptures had a special repercussion in France, in the second half of the 19th century. Around 1870, the demand for pieces suggested the characterization of the so-called “estatuamania”, a name that solidified the celebration of historical republican characters as a political-pedagogical initiative. Thus, both in France and in Brazil, the registration of public statues sought to symbolically strengthen the ties between the State and civil society. In the course of the twentieth century, the production of sculptures spread to several cities in the country, adopting the most diverse styles and techniques [3].

Some researchers point out that the movements of May 1968 constituted a milestone in the history of public art14 created as a form of urban expression, especially when ethnic, sexual and racial minorities began to use murals to signal their social discontent, express their concerns and their aesthetic experiences. Urban art would be understood not only as an identity landmark, but also as a collective creative expression. Through this bias, we realize that the creative process of public art is intertwined with the construction of urban memory itself. However, this story is not just limited to the insertion of works of art in this context. As Peter Burke points out: “In different countries, people have different ways of remembering the past [12].”

A historical archeology of the cities, including the contemporary ones, provides different readings of the aforementioned question. The material culture and the social and political references impregnated in the historical monuments, in the denominations of space and in the archaeological remains keep codes used by social subjects to produce meaning aiming at meanings such as national identity and ethnic difference. Other memories manifested through the modes of artistic expressions and housing, also condense identity references [13-17].

The different ways of enjoying the heritage (archaeological, historical and cultural), relate to the origins of this population and imply the transmission of knowledge, the exercise of sociability ... The visibility of the images displayed in open spaces transmits to the observers (whether they are inhabitants or occasional passersby), a given reading of the city that suggests an understanding of urban memories and historical landmarks.

In short, we see the city space as the setting for several ways to preserve collective memory. If we refer to some particularities of the cities, we will be faced with statues, street names, parks, squares, schools, which recreate and they represent images of national and / or global history, eternalizing events, intellectual and political characters. These areas must be integrated into the cultural circuit of public art in its fullest sense, precisely because they welcome signs of memories (individual and collective) and references of history, both local and national.

Currently, the Institute of National Historical and Artistic Heritage (IPHAN), despite the numerous administrative restructurings that marked the performance of the autarchy and its creation in the Vargas government, its objectives and methods of action have been respecting the international commitments signed by the countries subscribed to the Heritage Convention (1972), led by UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization). As such, the recognition of Brazilian heritage was restricted to the listing of works of art, monuments and architectural complexes considered to be of high historical or ancient value.

Thus, we understand heritage as a privileged locus where memories and identities acquire materiality. When we refer to the concept of heritage, understood as a deeper expression of the “soul of the people” and as a “living heritage” that we have inherited from the past, we live in the present and pass it on to future generations; we recognize that heritage is historically constructed and correlates individuals’ sense of belonging to one or more groups. This reasoning of belonging assures them of a cultural identity, which constitutes a valuable support for the formation of the citizen; therefore, the right to memory and the preservation of the heritage of different groups constitutes an exercise of fundamental citizenship in order to create the bases for social transformations necessary for the community [18-21].

As historian Jacques Le Goff asserted, memory allows the survival of the past, since, through the exercise of symbolic thinking, history is eternalized in human consciousness. From this perspective, Le Goff highlights that the “cultural identity of a country, state, city or community is made with individual and collective memory”, from the moment that society is willing to “preserve and disseminate its cultural assets” begins the process called by the author as the “construction of the ethos culture and its citizenship ”.

The notion of heritage comes etymologically from the concept of “paternal inheritance”. According to Funari, this term in the Romance languages derives from Latin patrimonium and alludes to “property owned by the father or ancestors” or “to the monuments inherited from previous generations ”. For the archaeologist and historian, these expressions allude to moneo, which in Latin means “to lead to think”. Consequently, the notions of cultural heritage remain linked to those of remembrance and memory - a basic category in the sphere of patrimonial actions, since cultural goods are safeguarded due to the meanings they awaken and the links they maintain with cultural identities [22- 24].

Only in the last years of the last century did the safeguarding of natural and cultural goods started to be accepted as a positive and intelligible gesture. The meaning of heritage has expanded and is not limited to the definition of archaeological sites, works of art, monuments, architectural ensembles or ancient objects referring to representations of political power. This notion was extended to different ways of living, forms of language, gastronomy, celebrations, in short, ways of using goods, physical spaces and the landscape. The rise of symbolic goods to the status of heritage, stimulated society (especially minorities and ethnic groups). The understanding that the patrimony was not limited to the goods of the dominant elites made it evident that the very concept of patrimony and the actions in its safeguard appear as social constructions,

Final Consideration

In the face of numerous challenges, the attitude of protecting local heritage should be encouraged, in order to safeguard the plural roots of peoples and their cultural traditions, since they express ethnic origins and imply the conservation of their identities and memories. In order to add the resident population to the “living legacy” of the history of their city or region, it is imperative to adopt pluralist heritage policies, capable of valuing environmental diversity, cultural heterogeneities and multiple identities, in order to foster coexistence between man and the environment and ensure the social inclusion of citizens. These measures must start from the point that the society that does not respect the archaeological, historical, cultural, artistic, national heritage and in all its diversity,

Another measure to be sought is the systematic and continuous education of the population through the methodologies of Heritage, Archeological and Environmental Education, which should promote training and clarification about the process of construction of ethnic identities and enable the development of reflections on around the collective and plural meaning of history and preservation policies. Furthermore, it can stimulate the desire to maintain past practices without ignoring the benefits of technology, offer discussions about the management of protected areas and parks, as well as the nuclei that aggregate them, aiming at the maintenance of protected assets (for example, the bust Carlos Lamarca) and preserved in the social and economic dynamics of the region or city in which they operate. This is still a particularly sensitive issue in Brazil, a country made up of an enormous diversity of local historical and cultural contexts and where a large portion of the population does not have access to minimum resources, including education. For this reason, the recent practice of Public Archeology in Brazil is a stimulating and encouraging challenge.

In addition, it is essential that in addition to safeguarding the Park’s Preservation Units, including their nuclei, they also recover the degraded physical area; the explanatory panel with the photos and information of Carlos Lamarca and mainly his bust, which has the urgency to be recognized for its value. It is necessary to follow the objective content of the work, to analyze its plastic intentionality and the subjective load of its formulations. For that, one must observe the bust of Lamarca as a document that raises the understanding of certain contexts and historical memories, such as that of the military dictatorship, a significant period for the political history of the country, which we cannot let fall into the oblivion, mainly in the face of the current Brazilian political context of serious threat to the democratic state. Therefore, we must once again emphasize that it is imminent to promote respect for heritage and cultural diversity. We search through this article to emphasize the importance of Public Archeology for the understanding of the public in which archaeological research is inserted through the process of social interaction, which enables society to associate itself with the cultural heritage as a whole and encourage its preservation. We hope that the notes of this work can contribute in this direction and mainly with the recovery of the bust of Carlos Lamarca together with his memory.

To Know more about Archaeology & Anthropology

Click here: https://juniperpublishers.com/index.php

No comments:

Post a Comment