Forensic Sciences & Criminal Investigation - Juniper Publishers

Abstract

Tattooing was proposed as a creative way for self-expression of the individuality. In the present study we assessed possible association between tattoos and narcissistic personality characteristics. To this end we have evaluated the interaction between narcissism and presence of tattoos in young women. Young women (aged 18-35 years) with (N=60) and without (N=60) tattoos completed the Narcissistic Personality Inventory (NPI). Women with tattoos had received significantly higher scores of the Exhibition subscale of the NPI than those without tattoos. A logistic regression analysis demonstrated that high level of Exhibition subscale and low level of education are significant contributors to getting tattoo amongst young women.

Keywords: Tattoo; Narcissistic Personality Inventory (NPI); Exhibitionism

Background

Recently tattoos became an intriguing social phenomenon studied in several scientific disciplines such as criminology, sociology, ethnography, psychology, psychiatry, dermatology, and others. With time, tattoos became popular and entered the mainstream [1-6]. The tattoo industry continuously grows and the percentage of people getting tattoos has increased to such an extent that tattoos have become socially acceptable today [7,8]. This encoding of class on the body creates a physical standard of relatedness to higher social classes [9]. Permanent forms of body decoration such as tattoos are perceived as part of individual preferences related to the self- identity [10-14]. In a prospective study [15] showed that obtaining a first tattoo leads to a significant improvement in self-perception and immediate feeling of uniqueness. Thus, getting tattoos is frequently aimed at improving self-perception [16,17]. Despite increasing acceptance of tattoos, society has a long history of viewing the tattoos in context of deviant behavior with a social stigma [18-24]. Silver et al. [25]. found that among 13,101 adolescents’ tattoo acquisitions were predictive for prior negative self-appraisal. In a sample of 4,700 participants, self-reported experience of physical, sexual, and mental abuse and general emotional abandonment was significantly associated with tattoos, especially in the women [26]. Getting tattoo was associated with a high rate of self-injurious behavior [27], and suicidal attempts [28-30]. Dhossche et al. [31] analyzed data from 134 adolescent with lethal suicides and accidental deaths; the percentages of individuals with tattoos were 21% and 29%, respectively. A data analysis of 4,700 individuals who responded to a Web site (www. bmezine.com) for body modification, found that 36.6% of the males had suicidal ideation, and 19.5% had attempted suicide. The rates were significant higher for females: 40.8% and 33.3%, respectively [29]. Persons who have tattoos, show a wide range of externalizing problems such as tobacco, alcohol and drug use; a large number of sexual partners, unprotected sexual intercourse with strangers [30,32- 35]; academic difficulties, risky body health behavior [23,36- 38], “truancy” problems, pathological gambling, gang affiliatio [39] aggressive outbursts [27,40], a history of criminal arrest [30]. Jennings et al. [41] suggested that having tattoos can be considered as a developmental risk factor and an expression of personality traits. Psychological explanations for getting tattoo appear to remain unclear [14, 42].

Some researchers suggested that tattooing behavior may represent a marker of personality maladjustment [43-47], or complicated self-esteem [48]. Numerous studies linked tattoos with adolescent psychopathology [29,31,49] and adult antisocial behavior [30,35]. Swami et al. [50] suggested that between-group differences in the personality traits of persons with tattoos have been grossly overstated. Although there are some betweengroup differences in a range of personal traits, the effect sizes are small and negligible [38, 51, 52]. It is unclear whether tattoos serve as a sign of personality characteristics via self-expressive artwork. It is possible that tattoos express the need for external self-affirmation and self-esteem [53]. Persons with tattoo tend to rate themselves as more adventurous, creative, individualistic, and attractive than those without tattoos [32,54,55]. The goal of this study was to reinvestigate the differences between women with and without tattoos by focusing on narcissistic-related personality characteristics using psychometrics measures. A major shortcoming in similar previous studies is under-evaluation of the female (women) population [56]. In the present study, we evaluated in young women the relationship between having tattoo and narcissistic traits as measured by the Narcissistic Personality Inventory (NPI) [57]. Narcissism as measured by the NPI score is viewed as a continuum from adaptive forms to maladaptive narcissism [58,59]. It is of note that clinical psychopathological aspects of narcissism, such as personality disorders, were not included in this continuum [60]. Narcissism has been defined as a multifaceted construct consisting of seven components: autonomy, entitlement, exhibitionism, exploitation, self-sufficiency, superiority, and vanity [59,61,62]. It was reported that characteristics measured by the NPI correlated positively with the need for uniqueness [57]. For this reason, getting tattoo became with time more individualized and very personal [55]. However, the association between self-reported narcissism and having tattoos was not studied previously. The NPI measures were used to determine to what extent young, tattooed women exhibit more narcissistic characteristics compared to their non-tattooed counterparts. We hypothesized that: (1) Young tattooed women would have higher total score on the NPI than non-tattooed women; (2) Young tattooed women would report higher scores of the Exhibitionism subscale of the NPI than non-tattooed women.

Methods

As described previously [63,64], all women with and without tattoo were recruited through advertisements posted at the university, personal contacts and social networks (Facebook), to take part in a research project investigating decision making styles in tattooed women and those without tattoos. Recruitment took place in the Tel Aviv area from March 2012 to July 2012. Participants in both groups (research and control) were either employed, students or graduates and from a similar socioeconomic background. The participation in the study was voluntary, without payment. Compensation for participating in the study was a free of charge consultation about their inhibition capacity and professional advice regarding their neurocognitive and personality assessments. The study was approved by the Bar-Ilan University Review Board (Ramat Gan, Israel), and was conducted through individual sessions with an explanation regarding the research aims and with the subject’s signing a consent form. The duration of an individual session was up to an hour and half, with the entire research process taking place over a period of five months. Sixty young women with tattoo, aged 18 to 35 years old (M=28.4, SD=5.95) were included in the study. Fifty eight percent of the tattooed women had more than one tattoo. All the participants were employed or students with education level: high school diploma or lower – 46.7%, first university degree – 25%, second university degree– 23.3%, and philosophy degree – 5%. We analyzed only women in order to avoid gender differences on the NPI scales. Previously, it was found that men tended to be more narcissistic than women were, and this feature was not explained by measurement bias and thus can be interpreted as true sex differences [65]. The exclusion criteria were neurological disorders, mental retardation, alcohol and substance abuse/ dependence (other than tobacco smoking), major psychiatric disorders and treatment with any psychiatric medication. Fifty-five percent of the participants with tattoo were smokers in contrast to 10% in the non-tattooed women. A semi-structured interview of a 20item measure of tattoo characteristics was administered by a researcher (AK). The control group included 60 women without tattoo, recruited from the same area in a similar age range: 18-35 years old (M=28.5, SD=5.43). Education level in the control group had the following distribution: high school diploma or lower – 25%, first university degree – 28.3%, second university degree – 41.7% and philosophy degree – 5%. All participants completed a screening interview, which covered the following areas: medical history, illicit drug use, family and personal psychiatric history. All of the subjects were free of any psychopharmacologic treatment. Exclusion criteria for the control women without tattoo included any current or past DSM-IV-TR axis I psychiatric disorder. Only 10% of participants from this group smoked regularly.

Narcissistic Personality Inventory (NPI)

NPI is a 40-item measure of Narcissism (M=17.85, SD=7.6, α=.86) [59]. This measure is frequently used in the study of narcissism, particularly in the field of personality psychology, and has been validated using a wide array of criteria for a review, see [53]. NPI is a self-report inventory, based on the DSM-related definition of Narcissism as a continuum, in which extreme manifestations represent pathological narcissism but less extreme forms reflect subclinical narcissistic personality trait [57]. The NPI consists of the following independent but correlated factors: authority (dominance, assertiveness, leadership, selfconfidence), exhibitionism (exhibitionism, sensation-seeking; lack of impulse control), superiority (capacity for status, social presence, selfconfidence), exploitativeness (rebelliousness, nonconformity, hostility, lack of tolerance or consideration of others), vanity (regarding the self, and being judged by others, as physically attractive), self-sufficiency (assertiveness, independence, self-confidence, need-for-achievement), and entitlement (ambitiousness, need-for power, dominance, hostility, lack of selfcontrol and tolerance for others) [59]. The internal reliability of the full scale is .83, with the 7 subscale reliabilities ranging from .50 to .73 [59]. The full scale also has high test-retest reliability after 13 weeks (r = .81); the test-retest reliability on the individual subscales is lower (range: .57 to.80; [66]. A Hebrew version of the questionnaire was developed [67]. Analysis of a normal population showed similar characteristics to those found in studies using this questionnaire in English. Reliability of the Hebrew version was tested using Cronbach’s alpha,which was 0.9 and the validity of the scale was 0.88 [67].

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using SAS 9.4 software for Windows. All analyses used two-tailed levels of significance. In the first stage, the parametric t-test was performed to compare groups (tattooed and not-tattooed) differences in demographic variables (age and education) and narcissistic characteristics (authority, exhibitionism, superiority, vanity, exploitative, entitlement and self-sufficiency). In the second stage, the multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to assess the relationship between the presence of tattoo and significant variables identified in the first stage. Multivariate logistic regression models were built using backward stepwise techniques considering variables with a univariate p-value≤0.25 (Hosmer & Lemeshow) as potential independent risk factors. The odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence interval (CI) were assessed for each predictor. A c-index was calculated to evaluate model discrimination, and the HosmerLemeshow test was applied to evaluate model calibration.

Result

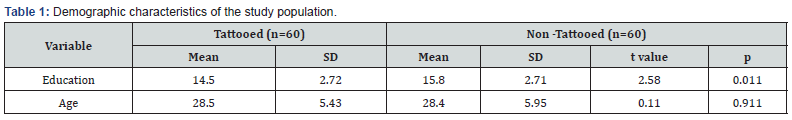

Between-group comparison of the socio-demographic characteristics. There were no statistical differences (on the level p=0.05) in age between the groups (Table 1). Women with tattoos were significantly less educated (t= 2.60, df= 118, p = 0.01) with effect size value of d=0.48, indicating a moderate power. Thus, education was considered as a covariate.

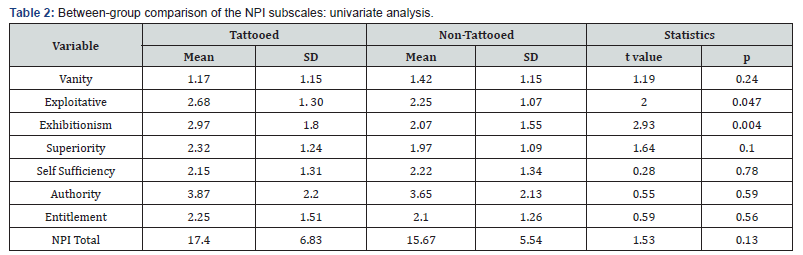

Between-group comparison of the NPI

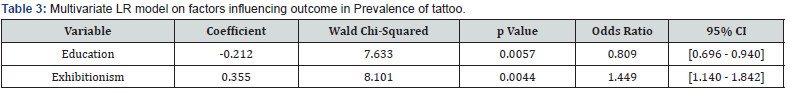

Total NPI scores of both groups were in the normal range. Univariate analysis showed significant differences between women with tattoos and women without tattoos in two NPI subscales: Exploitative (t=2.00, df=118, p=0.0478) and Exhibitionism (t=2.93, df=118, p=0.0041) (Table 2). Cohen’s effect size values for Exploitative (d = 0.36) and for Exhibitionism (d = 0.54) were at the moderate and high ranges, respectively (Table 2). All variables with univariable significance of p<0.25 were included in multivariable analysis. Multivariate backward logistic regression found that education and one narcissistic characteristic - Exhibitionism contributed significantly to a standard logistic regression model aiming to discriminate between participants with and without tattoo (Table 3). Based on the results from the multivariate logistic analysis, an institutional model was developed to predict outcome in tattooed participants. The results showed that the probability (p) of the response fits the equation:

log(9 /1− p) = 2.2492 − 0.2119*Education + 0.3709*Exhibitionism

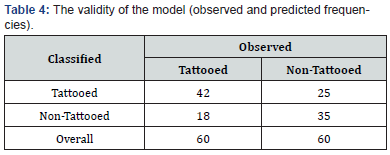

According to the model, education has a negative effect on the presence of tattoo. Participants with a lower education were more likely to have tattoo. The odds ratio of 0.809 shows that increasing education by one-year decreases odds of having tattoo by almost 21%. The Exhibitionism scale has a positive impact on the presence of tattoo, the higher this scale, the more likely that participant would have tattoo. The odds ratio of 1.449 for this scale shows that as this scale increases by one unit the odds of having tattoo, an increase of almost 45%. The resulting model had a c-statistic of 0.713, indicating moderately good discriminative ability. The Hosmer – Lemeshow Goodness of fit test was insignificant (p= 0.979), suggesting that the model fit the data well. The validity of our model with the cut off set 0.5 is presented in Table 4.

Discussion

In contrast to our expectation, total narcissism score on the NPI did not differ between women with and without tattoos. A post hoc analysis (including effect size) detected significant differences between women with and without tattoo only in the Exhibitionism subscale of the NPI. Exhibitionism as a dimension of the NPI includes sensation seeking and attenuation of impulse control [59]. Our observation of an elevated Exhibitionism subscale score in women with tattoo is in accordance with previous studies that demonstrated high scores of “experience seeking” [68] and “sensation seeking” dimensions in tattooed individuals [32,47,69,70]. Our finding is also in line with previous reports that showed that tattooed individuals had significantly lower Conscientiousness [15,52] and Agreeableness [52] on the NEO-PI, and express a significantly higher elevation on the psychopathic deviate scale of the MMPI than individuals without tattoo [71]. . In our previous study we demonstrated that young, tattooed women have difficulty in considering the cost and benefits of their actions [63], which is consistent with the previous observation of high risk-taking behavior in this population. Tate and Shelton [52] found that the “effect sizes of personality differences accounted only for 2% of the variance differences between tattooed and non-tattooed persons”. In the current study, by using the NPI, the effect size values regarding personality differences reached a moderate level. Moreover, only one specific narcissistic trait, namely exhibitionism, discriminated between tattooed and nontattooed young women.

Limitations

This study has several limitations that should be noted. First, we focused on young women (aged 18 to 35 years), thus, our results cannot be applicable to all the tattooed population. Second, we did not assess comorbid personality disorders in our sample, a factor that can affect our findings. Third, most of our young women had a small number of tattoos. It is possible that in women with a large number of tattoos the elevation in NPI scores is larger and not limited to one subscale.

Conclusion

The current study has demonstrated that young women with tattoos have significantly higher levels of exhibitionism and lower level of education than young women without tattoos. The hypothesis that special body ornaments such as tattoos may be a direct expression of exhibitionism warrants further studies including a systematic assessment of the relationship between the number of tattoos, their content and narcissistic personality characteristics.

No comments:

Post a Comment