Palliative Medicine & Care International Journal - Juniper Publishers

Objectives: Characterization of the population above 84 years of age, focusing on the site of their death, fragility and main morbidity that lead to a follow-up in the Palliative Care clinic.

Methods: Retrospective transversal observational study to characterized a population with 85 years of age or more, referenced from hospitalization to a Palliative Care team at a Portuguese hospital (Pedro Hispano Hospital), over a period of three years, focusing on the site of their death in relation to their main disease, their Charlson Comorbidity Index and the type of PC follow-up.

Results: Most patients died at the hospital, with non-cancer patients having a higher in-hospital death than the cancer patients. The most common morbidity was gastrointestinal and lung cancer, followed by heart failure and dementia in non-cancerous patients. Most of them died in the first month after the first PC team evaluation.

Conclusion: Timing of death remains unpredictable until late in the course of serious chronic illness. Therefore, special arrangements for care near the end of life, especially in non-cancer patients, should alert doctors to an early referral to the local PC team, in articulation with the primary care physicians and nurses, in order to allow patients to die at their preferred location.

Keywords: Palliative care; Very elderly; Aging place of death; Cancer; Non-cancer

Introduction

According to The World Bank, in 2018 around 3.66% of the worlds’ population was older than 80 years [1]. Population is ageing, leading to a dramatic increase in the numbers of people living above their seventies. Although most deaths occur among people who are older, there is relatively little policy concerning their specific needs towards the end of life. Treatment decisions for seriously ill older patients are often medically and ethically complex [2].

Patterns of disease in the last years of life have also been changing, with more people dying from chronic debilitating conditions, such as cardiovascular disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes, cancer and dementia [2]. The elderly is not only confronted with aging and multimorbidity, but also increasing frailty, disability and dependency. So, competing goals of care give rise to the debate of restoring function and prolonging life versus minimizing suffering and permitting a peaceful death [3,4].

The increased susceptibility of older people to adverse health outcomes paired with the cumulative effects of various chronic health problems result in prolonged, complex and fluctuating needs and symptoms in the last years of life [4]. Here, people experience symptoms such as pain, anorexia, low mood, mental confusion, insomnia and problems with bladder and bowel control. Symptom control is the basis of Palliative Care (PC), providing comfort, reassurance and support for the patient and their family or carer. Thus, it is necessary that PC services are develop to meet the complex needs of older people. It is urgent that these services become available for people with diseases other than cancer and are offered based on need rather than diagnosis or prognosis [2].

Everyone has a right to receive high-quality care, allowing for an end-of-life symptom free, dignified and in line with their physiological, spiritual and religious needs and wishes. Therefore, it is easy to comprehend why PC should have a central role in aging and the process of dying. By analysing the site of death in 14 countries, a group of epidemiologists in 2015, concluded that around the world, between 13% and 53% of people died at home and 25 to 85% died at the hospital. The large differences between countries in and beyond Europe in the place of death of people in potential need of palliative care were not entirely attributable to sociodemographic characteristics, cause of death or availability of healthcare resources, which suggested that countries’ palliative and end-of-life care policies may influence where people die [5].

Methods

We conducted a retrospective transversal observational study, by which we characterized a population with 85 years of age or more, referenced from hospitalization to a Palliative Care team at a northern Portuguese hospital (Pedro Hispano Hospital), over a period of three years (between May 1st of 2016 and May 1st of 2019). We evaluated the place of their death in relation to their main disease, their Charlson Comorbidity Index (as a translator of frailty) and the type of PC follow-up [6].

The statistical treatment of the data was conducted through IBM SPSS®, version 20. The categorical variables are presented as frequencies and percentages. The continuum variables are presented as median and standard deviation, all with a normal distribution. It was considered that a statistically significant result would not exceed the level of significance of 5% (p < 0,05). The study was conducted according to the recommendations of the Declaration of Helsinki of the World Medical Association [7,8].

Result

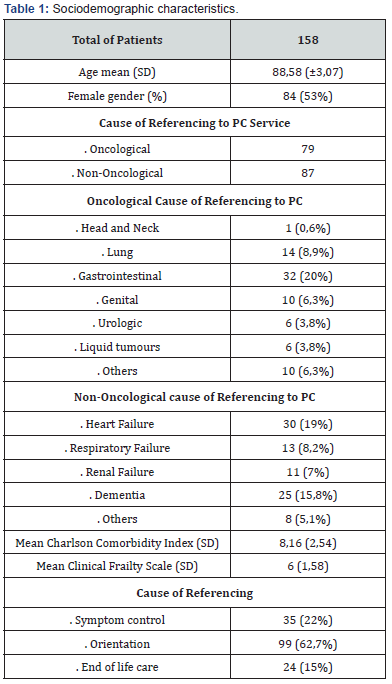

The sociodemographic characteristics of the 158 patients, in which 53% were women, are shown in table 1. The mean age was 88 years. There was a levelled percentage of patients with (n 79) and without cancer (n 87), with a total of 8 patients having both oncological and non-oncological problems in need of PC services. The main morbidity being gastrointestinal cancer in 20% of the patients with oncological conditions and heart failure in 19% of the non-oncological group. When it came to the Clinical Frailty Scale, there was a mean of 6 which corresponds to being moderately frail in people that need help with all outside activities and with keeping house and need help with bathing and might need minimal assistance (cuing, standby) with dressing. Regarding Charlson Comorbidity Index the mean value was 8.16, with a correspondence of 2% chance of an estimated 10-year survival. Most patients were referred to the PC team for further orientation at the time of discharge (62,7%) [9,10].

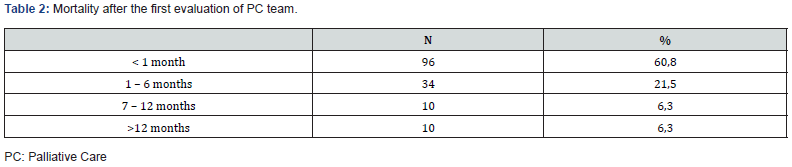

Of the 158 patients, 52% (n 82) died during that same admission. Of the 76 patients who were discharged, 59% (n 45) were followed regularly by the PC team, while 39% (n 30) stayed with a consulting approach. Regarding the overall mortality rate, 61% of the patients died in less than a month after the first evaluation of the PC team, with 8 patients still being alive at the date of this study - Table 2. When looking at the place of death, 100 (71%) patients died at the hospital bed (at the same episode or a different one, latter on), while only 41 died at home. Table 3 shows the relation between the site of death and other variables. A total of 75,7% of oncological patients followed by the PC team died at home compared to 50% of non-oncological patients, with a statistical significance (p 0,035). We found a statistically significant relation between dying at home and the type of followup provided, with more patients in shared care dying at home (74.4%, p 0.049). In gender, cause and motive of referencing no significant statistical difference was found [11,12].

When looking at the continuum variables, we found that the mean Charlson Comorbidity Index was higher in patients who died at home (8,46) compared to those who died at the hospital (7,55), with a p value of 0,08. Age of referral and the Clinical Frailty Scale was similar in both groups, with no statistically significance found - Table 4.

Discussion

We conducted this study in order to analyse a specific population, that will undeniably increase in the years to come. Most of the very elderly are referred to PC team due to end stage diseases, meaning they are referred at a late stage of their conditions, limiting the range of action of the team (7; 10). Our series shows a high death rate in the first six months of follow-up after the first evaluation, with over 80% of total deaths, meaning that these elderly patients may be referred at a very late stage in their conditions. Most of the patients are referred to the PC team in order to define the better approach when thinking about discharge home, which means most of the inpatients have a later evaluation during the hospital admission. In our population, the most common conditions at this late stage in life, were gastrointestinal and lung cancers, heart failure and dementia. This is in accordance with the literature and expected according to the latest trends, with advanced cancer being the most common condition followed by chronic kidney disease and heart failure Dementia is viewed in most articles has a comorbidity and not has the main condition [13]. According to a WHO report from 2014, regarding Palliative Care at the End of Life, 7.786.470 deaths worldwide were related to cancer compared to 18.134.342 deaths non-oncological related, with cardiovascular diseases and chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases [14].

If on one hand, specialist PC has historically been offered to patients with cancer and only in the last years has their value to those with non-malignant conditions been recognised. What we know now is that nononcological patients have comparable levels of need to people with cancer and are at risk of poor outcomes, such as distressing symptoms or social isolation [6]. Our series shows a fifty/fifty distribution of oncological and non-oncological cases, possibly related to the age of our referred patients. It is difficult to find data in the literature regarding oncological versus non-oncological conditions in PC, with a few articles mentioning a disproportional distribution between oncological and nononcological conditions. A series with 272 individuals followed by PC team of Hospital Pedro Hispano in 2018, reported that in the overall population, 87.5% of patients had oncological disease and 12.5% non-oncological conditions [15,16]. This is possibly related to the lack of objective referencing guidelines and criteria regarding aging and patients with multimorbidities [7]. Evidence of specific needs among older frail people is limited, mainly because most of the guidelines and approaches in PC setting have been developed based upon and aimed at cancer patients [15]. As so, Coventry et al proposed that a survival estimate of < 6 months may be used as some guidance towards defining appropriateness and timing of PC referrals in non-oncologic patients.

When looking at morbidities, cancer patients had a higher Charlson Comorbidity Index from the start, meaning that this group has a lower estimated 10-year survival. This was in accordance with the result of the higher the index the bigger the rate of death within the first year of follow-up by the PC team [9]. When searching for other variables, most oncological patients were followed in a shared care concept, as opposed to non-oncological patients who were mainly on a consulting type of follow-up. One can speculate if these findings may be responsible for the fact that cancer patients died more ate home than at the hospital, when compared to non-oncological patients or simply because oncological conditions have a better defined and expected trajectory. PC have a central role through symptom management outside the hospital and improvement of the quality of end of life care, while respecting patients’ wishes and believes [10].

Conclusion

Timing of death remains unpredictable until late in the course of serious chronic illness. Therefore, special arrangements for care near the end of life, especially in non-oncological patients, can be triggered by severity of symptoms, rather than waiting for a reliable prediction that death is near.

It is possible to live comfortably, even with serious chronic illness. But living with such illness requires planning for the ongoing course so that services match the course of the illness. Timing of death remains unpredictable until late in the course of serious chronic illness. Therefore, special arrangements for care near the end of life, especially in non-oncological patients, can be triggered by severity of symptoms, rather than waiting for a reliable prediction that death is near. Serious chronic illnesses require continuity and comprehensiveness of care, with needs generated by symptoms or disabilities being urgent priorities. The studies conducted regarding the preferred site of death, show the majority preferring to die at home [12]. Direct enquiry and identification of preferences for end of life care may help determine the type of follow-up a PC team provides for their patients, working together with the rest of the medical team (primary care and hospital care) in order to try and satisfy the patients and the families wishes.

I wasted a lot of money trying to find the right medication for my moms dementia all to no avail until Dr Erayo showed up and eradicated the stigma with the natural roots and herbs i ordered from him , my mom took it for 21days and she was cured from her dementia.

ReplyDeleteGod have use Dr Erayo herbal home to cure my mom, thank you so much Dr Erayo I am so happy. You can email Dr Erayo for help drerayoherbalhome@gmail.com

or whatsapp him on +2348151937428

website---- https://alternativeherbs.weebly.com

Youtube link---- https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCSp2m-_EHnCRQT4gYYTQWtg

FB page---- https://rb.gy/yuofn6