Haitian officials, in line with most country leaders

around the world, announced a series of health, hygiene and safety

precautions following the COVID-19 global pandemic early in 2020. The

tiny nation (10,714 square miles) situated on the island of Hispaniola,

still recovering from the devastating 2010 earthquake, which claimed the

lives of close to two hundred thousand people, seemed prepared to take

on the challenges of COVID-19. Businesses and schools immediately

closed, face masks and hand sanitizers were distributed by the

thousands. But the effects of emergency injunctions that were not geared

towards capacity-building, but rather prevention of rapid infectious

disease transmission, could prove debilitating for the impoverished

nation over the long-term. Primary and secondary school enrollment rates

in Haiti are at an all-time low, and projections for the Haitian

economy are dismal (-3.5% GDP growth 2020f) (World Bank 2020: 27). As a

retrospective study, this paper conducts a critical quantitative and

qualitative analysis of humanitarian aid, gender-based violence, and

urbanism in Haiti, revealing that gender-responsive planning has a

greater role to play in state-led disaster management plans and

procedures for achieving long-term equity and sustainable economic

growth.

Keywords: Urban informality; Gender-Based Violence (GBV); Gender-Responsive Planning; Humanitarian aid; Earthquake; Haiti

Le Nouvelliste reported that emergency units at

l’Hôpital de l’Université d’État d’Haïti (HUEH) (State University of

Haiti Hospital) were overwhelmed by the COVID-19 pandemic in early

spring 2020. With no quarantine units at HUEH and only 37 of 124 ICU

beds nationwide meeting international ICU standards for a country of

more than 10 million people [1], critical care units could not meet

testing and treatment requirements of COVID-19 patients. How was it

possible that nearly a decade after receiving more than 300 million USD

from intergovernmental agencies for capacity-building projects, the

Haitian healthcare system was operating with only 37 ICU beds? Following

the January 12, 2010 earthquake, the Interim Haiti Recovery Commission

(IHRC) was established to manage the implementation of aid programs in

Haiti. Operating with over 300 million USD in funding from the U.S.

government, the IHRC, co-chaired by the Government of Haiti (former

Haitian Prime Minister Jean-Max Bellerive) and the UN Special Envoy to

Haiti (former U.S. President William J. Clinton), had as its mandate: 1)

Creation of new jobs in textile

and manufacturing; 2) Support for people with disabilities; 3)

Development of microfinance opportunities for small businesses; 4)

Expansion of the Haitian public education system with support from the

Inter-American Development Bank (IADB) and USAID; 5) Resettlement of

displaced persons; and 6) Major debris removal [2,3]. When the IHRC’s

mandate expired on October 21, 2011, little progress was made on the

aforementioned. During the tenure of the IHRC, limited attention was

given to soft infrastructure—the political and social systems in Haiti,

weakened by decades of political instability and violence—and the

important role that Haitian women have played in Haiti’s critical care

and rebuilding processes.

Gender-responsive planning calls for a defined

gender-focused plan or system that includes the linkages between public

policies, resources, social capital, and gender [4]. Gender-responsive

planning, policies, and approaches can include measures that take into

account the special needs of women and girls in health care delivery and

access; enhanced provisions for women in negotiating land use

agreements; and guidelines for protecting women and

girls under the judiciary and police force [5]. This article is a study

on gender-responsive planning in a post-disaster context through

an analysis of intergovernmental and non-governmental agencies

and their partial successes and failures in Haiti. Ultimately, this

work offers a framework for understanding the multiple impacts

of urban informality and gender-based violence (GBV); and

theoretical approaches for managing weak state failure and aid

effectiveness through gender-responsive planning.

Urban Informality in International Development

Urban informality and informal economy are the byproducts

of prescriptive and reactionary state and inter-organizationled

economic and social reforms. Structural adjustment reforms

forwarded by the World Bank and IMF as solutions to poverty

and debt promoted liberalization and privatization schemes

throughout the 1980s and 1990s in Latin America and the

Caribbean, Asia, and Africa. Structural adjustment reforms enticed

new investments in manufacturing and cheap labor to meet the

demands of international trade and quick output. However,

economic deregulation also meant lowered wages and limited

social protections, forcing many households into poverty and the

rapid urbanization of cities unprepared to meet the basic needs

(water, sanitation, housing) of poor, rural, migrants in search of jobs

in cities. Urban informality soon translated to people adapting to

life in impoverished conditions outside of formal laws or sanctions.

Some development economists like Hernando De Soto [6] might

celebrate urban informality as a reflection of human agency and

innovation amidst poverty, political oppression, and instability.

While other international development theorists might point

out that urban informality raises issues related to exclusion from

formal markets and distributive justice—who gets to own property

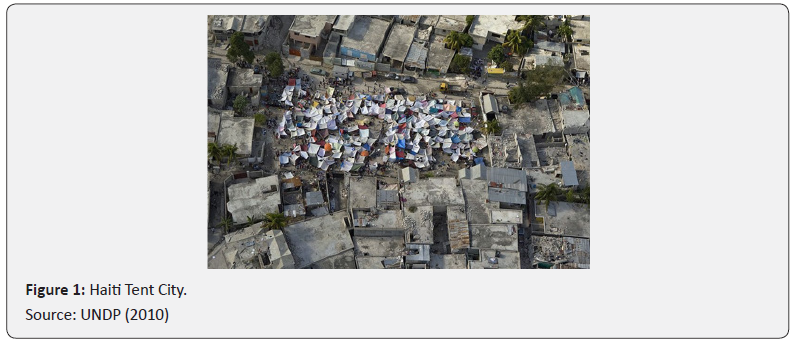

and who does not? [7]. Examples of urban informality include

informal housing subdivisions in the Global South, like tent cities

in Haiti, squatter settlements in India, or favelas in Brazil—that

although formed through cooperative land agreements between

individuals and families over decades, remain in violation of land

use laws. Extralegal transactions in urban informal economies

are frequently conducted under the auspices of formal state

officials, who sometimes participate in informal markets for their

own benefit. In Pakistan, “Karachi middlemen” serve as informal

intermediaries between poor migrants, squatters, shopkeepers,

and local authorities [8]. In the late 1940s, Karachi experienced

a swell in rural-urban migrants, partly because of rapid growth

in Pakistan’s textile and manufacturing industry promoted

under the Colombo Plan in 1951 for the Asia-Pacific region and

Pakistan’s Five-Year Plans, installed under the first Prime Minister

of Pakistan Liaquat Ali Khan in 1948 (ending around 1998-1999).

Where city and state officials were not financially or politically

equipped to deal with major shifts in population demographics,

housing and employment demands, middlemen came into play

[8]. Middlemen would meet the needs of low-income migrants in

Karachi, by collecting subsistence payments. These payments were

then exchanged through bribes or pay-offs for “rights” to create

and manage informal settlements and activities around the city

[8]. While the activities of modern-day middlemen have shifted

to meeting the consumerist aspirations of Karachi’s growing

middle-class, the continued influence of middlemen as community

stakeholders reinforces the idea that urban informality produces

both positive and negative externalities within middle and lowincome

state development.

The amalgamation of poor migrants and limited formal

employment opportunities, peri-urbanization, privatization

during the 1980s under El Gran Viraje (The Great Turnaround),

work stoppages, and public strikes created Venezuela’s presentday

barrios, or urban informal settlements that are now

permanent fixtures across the principal city of Caracas. With

President Chavez’s election in 1999 and social policy reforms

implemented under his administration, rates of poverty, extreme

poverty, and households in poverty saw an overall decline in

Venezuela: “the percentage of households in poverty declined

by more than half, from 54 percent in the first half of 2003, to an

estimated 26 percent at the end of 2008” [9]. Yet, the aftershocks

felt from repeated coup attempts (1992; 2019) have left the oilrich

nation still struggling to manage a deep debt crisis and social

unrest in the barrios.

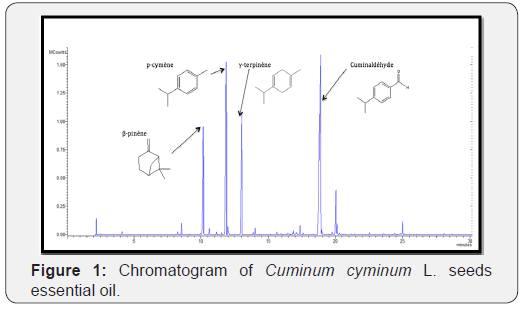

Urban Informality in Haiti

Well before the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic and 2010

earthquake, informal networks and informal aid substituted much

of the core state planning operations in Haiti. Like Venezuela

and Pakistan, urban informality in Haiti (Figure 1) was largely

the outgrowth of structural adjustment reforms instituted in the

1980s and 1990s by the World Bank and IMF, which encouraged

decentralization and privatization of public goods and services

[10]. Peri-urbanization, tent cities, shadow police forces, and

extralegal transactions for transport (tap taps), housing, and food

comprise urban informal economy in Haiti. A 2002 report from the

World Bank Report posed the question: “Is Haiti a decomposing

state?” “Est Haïti un état en decomposition?” The short answer

from the authors was no. The longer conclusion was that poverty,

informal economy, political instability, limited health and hygiene

services, informal unemployment and a weak judiciary system

made funds for poverty reduction ineffective, and Haiti susceptible

to persistent economic decline.

Informal Economy

Urban informality in Haiti operates as a socio-cultural

informal sub-economy with domestic and international informal

actors managing violence, cultural and social customs, and

abject poverty. Haiti’s informal actors can be likened to “informal

street-level bureaucrats”—who relying on trust, loyalty, and

reciprocity build formal ties with local officials to meet demands

such as food, health care, and housing in the community. Michael

Lipsky’s pioneering work on street-level bureaucrats in Streetlevel

Bureaucracy: Dilemmas of the Individual in Public Services

[11] posited that street-level bureaucrats exercised a great level

of discretion over the implementation of public policies. A social

worker, for example, enrolling clients into health care plans or

unemployment insurance at a one-stop center in the United

States must determine client eligibility through assessments and

interviews. In the absence of a strong state apparatus, informal

street-level bureaucrats make similar determinations, but operate

with higher transaction costs because of the heightened likelihood

of misinformation, corruption, and lack of social insurance or

protection.

Haiti’s “informal street-level bureaucrats” were present in the

days, months, and years following the 2010 earthquake, managing

donations, housing, and security around tent cities. After the 2010

earthquake, nearly 40% of residents in temporary camps reported

receiving informal aid, like cash remittances, from informal

sources like relatives and friends—not government agencies or

local authorities—while 32% received no material assistance

at all [12]. Formal assistance came in the form of donated tents

and tarpaulins from agencies like the World Bank, the Red Cross,

Catholic Relief Services, Islamic Relief, and Doctors Without

Borders [12].

Aid in the form of cash remittances is common in developing

countries: “In 2018, over 200 million migrant workers sent $689

billion back home to remittance reliant countries, of which $529

billion went to developing countries” [13]. Aid from “home”

through informal channels is perceived to be more reliable,

cheaper, and under less public administrative scrutiny. A 2003

survey on remittances in South Africa found that “remittances

up to R250 to neighboring countries cost R25 and R50, through

friends and taxi drivers, respectively, as compared with over R100

through registered banks and over R80 through money transfer

agents like MoneyGram and Western Union” [14]. Informal aid

remittances have also driven the development of mobile banking

technology in the Caribbean, Asia, and Africa as the preferred

channel for informal cross-border remittances, which increased

to 51.8% in 2015 [15]. Remittances to Haiti via formal channels

reached 3.3 billion USD in 2019, almost 37% of the country’s

GDP [16]—unrecorded transfers of money through couriers

though are projected to be higher [17]. The overall trend towards

informal aid remittances over the past two decades reflects

a growing Haitian diaspora and new technologies, outside of

traditional banking, that have facilitated informal aid assistance.

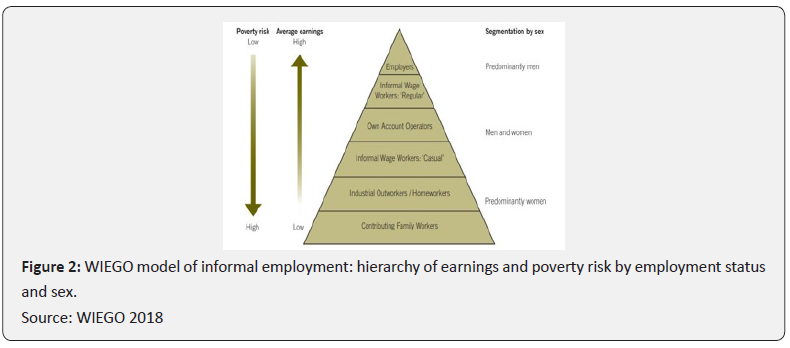

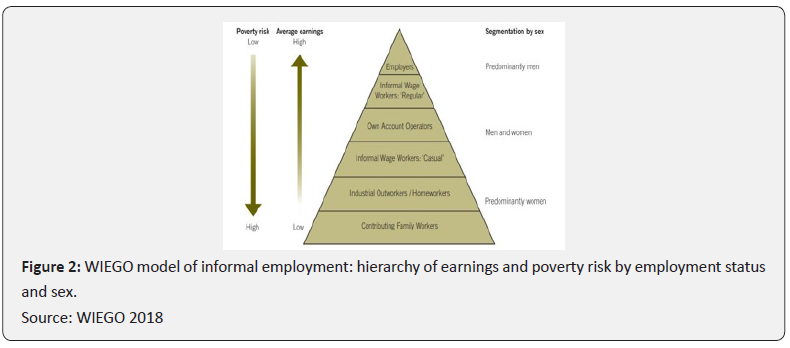

Informal economy through aid remittances however provides no

viable opportunities for formal employment or investment back

into the local economy. Rather, low wage workers in the informal

sector—especially women, employed as domestic workers, waste

pickers or street vendors—are subject to higher incidences of

economic and physical violence in abusive workplaces (Figure

2). Occupational gender segregation in the neoliberal era reflects

a gendered provisioning of goods, services and labor—or what

economist Nancy Folbre [18] calls “economies of care” that are

poorly regulated.

In Haiti, irregular and informal work has exposed women

to workplace violence and economic hardship with limited

alternative options. Surveys from the Haitian Institute of Statistics

and Information Sciences (IHSI) between 1990 and 2000 showed

that structural unemployment in Haiti was due in large part to

the prevalence of low skilled informal work and occupational

gender segregation. Women made up 60.7% of the unemployed

population, and men 43.1% [19]. Nearly 44% of all households

were female headed households, with women and girls employed

in the informal sector to varying degrees as cooks, nannies, or

housekeepers [19]. Young Haitian women and men seeking new

formal employment opportunities were often recruited through

informal channels to work in “bateys,” or sugar mill camps, in the

Dominican Republic, under the guise that they would eventually

receive formal citizenship status and economic rights as regular

wage earners. However, work in the bateys is typically dangerous

and laborers are often given fraudulent working papers that make

it almost impossible to regularize their status as agricultural

employees.

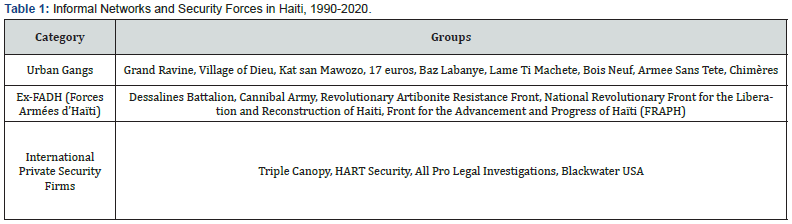

Gender-Based Violence (GBV) and Urban Informality

The 2006 film Ghosts of Cité Soleil, which introduced the

world to “Lele” Senlis, a French aid worker, and the leaders of

Chimères “Ghosts,” a notorious gang in Haiti’s Cité Soleil slum,

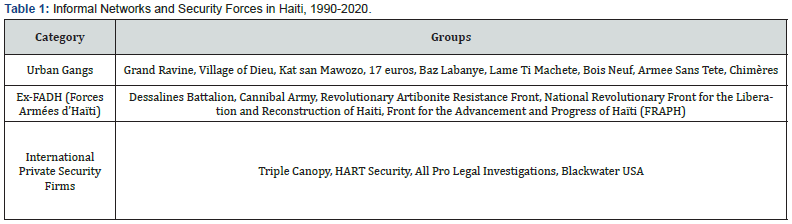

revealed the prominence of contemporary urban gangs in Haiti. In

the months following the 2010 earthquake in Haiti, international

private security officers, urban gangs like the Chimères, and ex-

FADH (Forces Armées d’Haïti—FAd’H) paramilitary units took

to patrolling Haiti’s tent cities and surrounding neighbourhoods

(Table 1) —sometimes in concert with, or compensating for the

Haitian National Police (HNP), already strained from limited

funding and tensions from political violence [20]. Informal

security networks and private security firms attending to foreign

dignitaries and UN peacekeeping forces committed or ignored

acts of gender-based violence in Haiti after the 2010 earthquake.

Doctors Without Borders reported treating two hundred and

twelve survivors of sexual and gender-based violence (GBV)

five months after the January earthquake [21,22]. The United

Nations Stabilisation Mission in Haiti (MINUSTAH), which ended

its thirteen-year mission in Haiti in 2017, came under fire for

accounts of sexual abuse involving Haitian children. Research

studies published in 2019 found that MINUSTAH personnel had

fathered hundreds of children, nicknamed Petit-MINUSTAH,

“little MINUSTAH,” with Haitian women and adolescents. Some

families had also received small allowances for child rearing from

MINUSTAH officials [23,24]. Instead of focusing on the underlying

causes of GBV in tent cities linked to informal security personnel,

and the spread of misinformation stemming from poor social and

economic supports, the IHRC, MINUSTAH, and other UN agencies

continued to argue that poverty, prostitution, and living conditions

in tent cities were to blame for the increase in rates of GBV. In a

January 16, 2011 press release, CEO of the UN Foundation, Kathy

Calvin wrote, “[Camp residents] need lighting so that women

and young girls can feel safer when walking to the latrines…

That is why the United Nations, the UN Foundation, and other

partners are distributing solar-powered lights to camps” [25].

Solar powered lights, while well-intentioned, were a band-aid

solution to the systemic violence, corruption, and mishandling of

GBV incidents throughout Haiti’s tent cities and slums. Managing

urban informality and GBV in Haiti’s tent cities would prove

pointless, so long as root-cause factors like systemic exclusion of

Haitian women’s organizations and misreporting of data, budgets,

and GBV were not addressed.

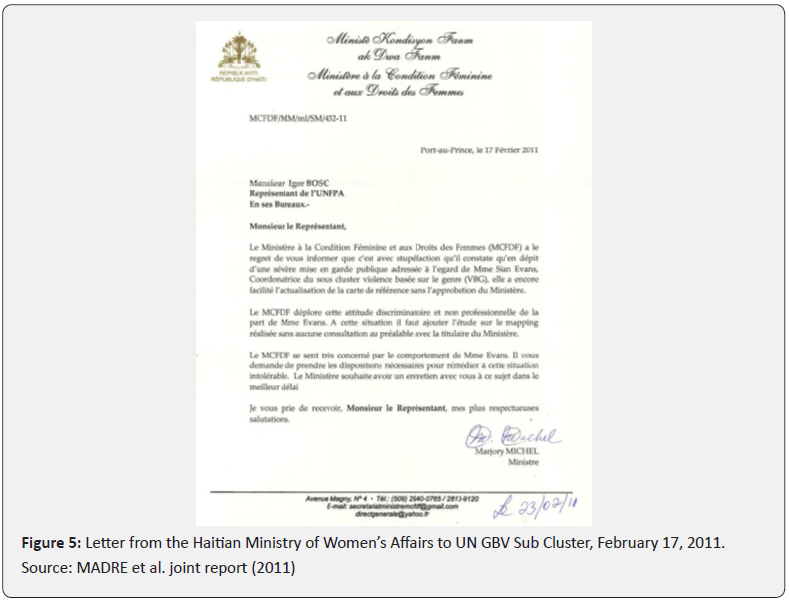

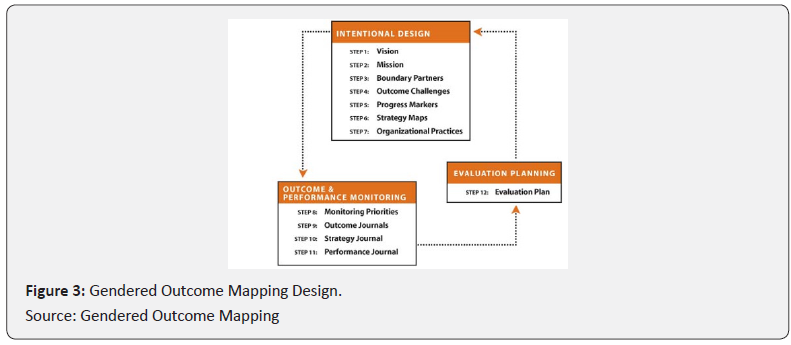

Gender-Responsive Planning

The unplanned and unplannable are frequently the outcomes

of unequal power relations expressed through state action or

inaction. Gender-responsive planning (Figure 3) as a mechanism

for state intervention, stresses a critical overhaul of country

assessment plans to include sex-disaggregated data, time use

studies, and strategic gender needs alongside practical gender

needs. Consensus on gender-responsive planning as a quantitative

and qualitative methodological approach to state planning,

monitoring, and evaluation plans grew out of the 1995 Beijing

Declaration and Platform for Action. The Platform reaffirmed the

“human rights of women and of the girl child as an inalienable,

integral and indivisible part of all human rights and fundamental

freedoms” (1995 Beijing Platform for Action: 2). The Platform also

urged government leaders to:

Gender-Responsive Planning

The unplanned and unplannable are frequently the outcomes

of unequal power relations expressed through state action or

inaction. Gender-responsive planning (Figure 3) as a mechanism

for state intervention, stresses a critical overhaul of country

assessment plans to include sex-disaggregated data, time use

studies, and strategic gender needs alongside practical gender

needs. Consensus on gender-responsive planning as a quantitative

and qualitative methodological approach to state planning,

monitoring, and evaluation plans grew out of the 1995 Beijing

Declaration and Platform for Action. The Platform reaffirmed the

“human rights of women and of the girl child as an inalienable,

integral and indivisible part of all human rights and fundamental

freedoms” (1995 Beijing Platform for Action: 2). The Platform also

urged government leaders to:

Analyse, from a gender perspective, policies and programmes

- including those related to macroeconomic stability, structural

adjustment, external debt problems, taxation, investments,

employment, markets and all relevant sectors of the economy

- with respect to their impact on poverty, on inequality and

particularly on women; assess their impact on family well-being

and conditions and adjust them, as appropriate, to promote more

equitable distribution of productive assets, wealth, opportunities,

income and services…(g) Provide adequate safety nets and

strengthen State-based and community-based support systems,

as an integral part of social policy, in order to enable women living

in poverty to withstand adverse economic environments and

preserve their livelihood, assets and revenues in times of crisis;

(1995 Beijing Platform for Action: 20-21)

Substantial scholarship on applied approaches to genderresponsive

planning support the 1995 Platform for Action.

Caroline Moser’s triple roles theory [26] and Naila Kabeer’s Social

Relations Approach (2005) for example provide a conceptual

framework for understanding gender-responsive planning as the

“interrelationship between agency, resources, and achievements”

and power sharing (Kabeer 2005: 15). Moser’s triple roles

theory describes how women are simultaneously reproducers,

community managers and wage earners [26]. Kabeer’s Social

Relations Approach explains that “social relationships…govern

access” to resources, labor, time, and services (Kabeer 2005: 13).

This scholarship has helped advance a greater understanding

of the consequences of transnational families, transnational

motherhood, social capital, female headed households, division of

labor, and female migrant networks. UN agencies have endeavored

to improve research on unpaid care work and the socioeconomic

contributions of women and girls in low- and middle-income

countries. Additionally, the push for more sex-disaggregated data

and time use studies through gender-responsive planning over

the past two decades has created a new field of opportunities

for critical research and intervention from NGOs and non-profits

around the world. In the Republic of Korea, researchers found that

unpaid care work was “equivalent to 4,407% of the value of paid

care work” [27]. On transnational families and public security, the

Romanian NGO Alternative Sociale determined that when mothers

migrated, despite a private care market of babysitters, tutors, and

surrogate care takers, there was still an increase in rates of school

absenteeism and dropouts [28]. This research has encouraged the

creation of new programming in education, maternal care, food

security, and criminal justice to support women, parents, and girls

globally.

Sociocultural factors have played an important role in shaping

how officials, citizens, and institutions in Haiti document and respond to GBV, complicating traditional gender-responsive

planning methods and approaches. Women in certain trade

unions and industries cited sexual harassment from peers and

supervisors, but many victims were either reluctant to report

the harassment or reports were disregarded by authorities as

“hearsay” [19]. Fear of reprisals, pressure, stereotypes, and

prejudice from the victim’s family or the perpetrator’s family were

also factors that impacted reporting and accountability on GBV.

A 2016-2017 “Mortality, Morbidity and Use of Services Survey in

Haiti” Enquête Mortalité, Morbidité et Utilisation des Services en

Haïti (EMMUS) for instance found that of the 14,371 Haitian women

surveyed between the ages of 15 and 49, more than 54% never

sought out help or spoke to anyone about incidences of emotional,

sexual or physical violence (EMMUS 2018: 17). Uneducated and

poor Haitian women were also less likely to receive information

from clinics on STDs and HIV/AIDS prevention and to negotiate

protected sex with partners, increasing the likelihood of “survival

sex” and other risky behavior [19] Of the approximately 150,000

adults living with HIV/AIDS in Haiti, 87,000, or 58% were women

in 2018. New infections were more prevalent among young women

between the ages of 15 and 24—1600 new HIV/AIDS infections in

2018 were among young women, less than 1000 new infections

were reported among young men (UNAIDS 2018).

Structural Factors

Building on momentum from the 5-year plan (2006-2011)

established by the “Concertation Nationale Contre les Violences

Faites aux Femmes,” “National Convention Against Violence

Against Women” organized by the Haitian Ministry of Women’s

Affairs, the Haitian Ministry of Health, and Prime Minister Gérard

Latortue, Haitian women’s organizations attempted to join

programming efforts of the UN GBV Sub-Cluster post-earthquake

[29]. However, their attempts were blocked by the UN GBV Sub-

Cluster [21]. In a joint report to the UN Human Rights Council in

April 2011, the international human rights organization, MADRE,

in partnership with Commission of Women Victims for Victims

(KOFAVIV), Women Victims, Standing (FAVILEK), and National

Coordination for Victims Direct (KONAMAVID) produced a report

titled “Limited Access to Medical Services, Lack of Adequate

Security in the Camps or Police Response, and the Exclusion

of Grassroots Organizations” on the alarming situation of GBV

in Haiti post-earthquake [21]. MADRE and its collaborators

also argued that rejecting Haitian women’s groups violated the

Inter-American Convention on the Prevention, Punishment and

Eradication of Violence Against Women (“Belém do Pará”), UN

Security Council Resolution 1325 and the UN Guiding Principles

on Internal Displacement.

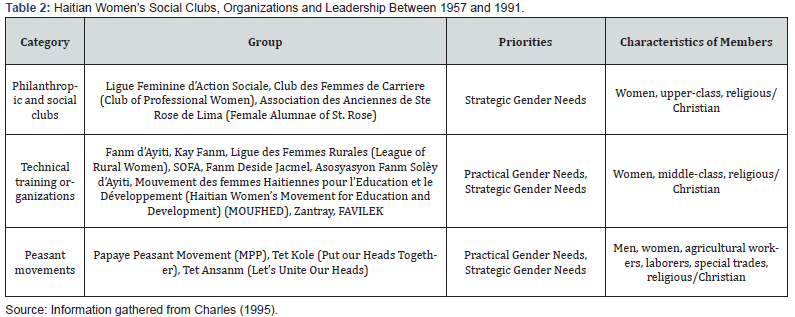

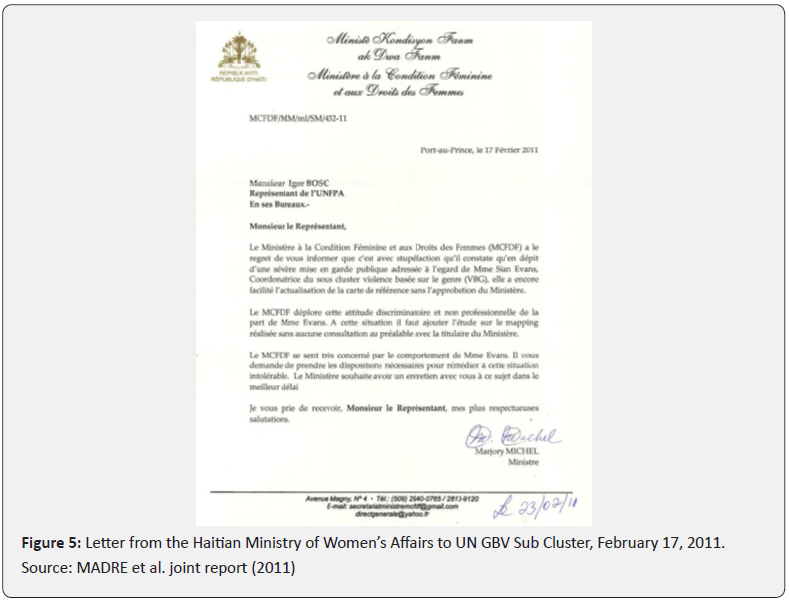

In a letter from the Haitian Ministry of Women’s Affairs to the

UN GBV Sub Cluster dated February 17, 2011, Minister of Women’s

Affairs Marjory Michel decried the deplorable conditions of Haitian

women and girls in tent cities—noting limited UN support for

women and girls on the ground and exclusion of Haitian women’s

organizations from UN planning and procedures post-earthquake

(Figure 4). However, with almost no accountability measures

in place to ensure transparency or a formal response, the letter

was ignored by the UN GBV Sub Cluster [21]. Reported feelings of

disrespect and mistrust set the tone for many of the negotiations

and meetings amongst Haitian and foreign leaders following the

2010 earthquake—with even President René Préval lamenting,

right after the earthquake, that the only people who seemed to be

with him were journalists trying to snap pictures of dead bodies

[30]. The crisis of leadership in Haiti had a direct impact on the

limited interventions of the IHRC. Early on, the IHRC 2010 Project

Proposal, responding to the concerns of grassroots women’s

organizations, had in fact integrated a section on “Protection,

Care and Support for Women who are Victims of Violence in

Haiti.” But the proposal suffered from three key omissions: 1) a

funds disbursement strategy for the 10.6 million USD budget

2) an actionable timeline with steps towards GBV prevention

programming 3) Haitian partners or NGOs that could assist with

program implementation (Figure 5). Weakened by organizational

mismanagement, and funds directed towards other immediate

crises (like food, medicine, and sanitation), the IHRC ended its

mandate as a missed opportunity to develop new institutions or

programs in education and health care that could have benefitted

Haitian men, women, and children past the 2010 earthquake.

Socio-political Factors

In the years before the 2010 earthquake, Haitian women and

Haitian women’s associations were severely underrepresented

within the legislative bodies of the Haitian government and

administrative positions of power. In “1990, the number was

down to 34 elected women: five as mayors, 17 as second member

of the Board and 12 as the third member. In 1997, only 6 of the

127 mayors were women. In 2000, there was a slight increase,

with 25 women being elected mayors in four Departments” [19].

In the 2015-2016 elections, the Institute for Justice & Democracy

in Haiti reported that women still remained underrepresented in

politics: “In the August and October, 2015 elections, 22 out of 232

senatorial candidates were women (12 percent)…Of the Chamber

of Deputy candidates, 129 out of 1621 were women (8 percent)”

[31]. Political activist and economist, Myriam Merlet who died

in the 2010 earthquake, argued that generally structural sexism

made it difficult for women to consider political careers in Haiti.

According to Merlet, systemic biases, women with lower levels of

educational attainment, and widespread beliefs that politics are

too “dirty” and dangerous for women contributed to low rates of

political participation [32]. To overcome structural sexism would

necessitate a greater focus on strategic gender needs at all levels in

government, health care, economy, and society. Whereas practical

gender needs are based on survival—“a response to an immediate

perceived necessity” “formulated from the concrete conditions

women experience” [33]—strategic gender needs refer to power

relationships in the delivery of health and human services.

Strategic Gender Needs

Oftentimes, practical gender needs attract more attention and

funding during crises and disasters since they relate to human

survival. However, strategic gender needs are “those needs which

are formulated from the analysis of women’s subordination

to men, and deriving out of this the strategic gender interest

identified for an alternative” [33]. Formal state officials mediate

strategic gender needs “between state and civil society…within

the family between men, women, and children”, which “has critical

implications for the identification of the ‘room to manoeuvre’ to

address strategic gender needs” [34]. Feminist epistemologies

on planning and ways of understanding gender through social

positioning compel a greater consideration of location, power, and

the lived, relational experiences of men, women and children—to

the extent “that practical gender needs only become ‘feminist’ if

and when transformed into strategic gender needs” [33]. Stateapproved

programs on women’s policies encourage the notion

that a state agenda on “feminism” does have a place in public,

political, popular discourse. Strategic gender needs move past

binaries of “survival-necessity” to state-led initiatives and public

programming on gender equality.

Implementing Strategic Gender Needs in the Haitian

Context

“State feminism” in Haiti was most visible throughout

the Duvalier regime between 1957 and 1971. The Duvalier

propaganda machine engaged women through political narratives

like the “Marie Jeanne”—daughter of the revolution [35]. This

increased politicization turned women from “political innocents”

to “political agents” –which not only created a new role for

upwardly mobile middle- and upper-class Haitian women in

Haitian society and economy, but also unleashed a wave of terror

against both men and women, considered enemies of the state

[35]. In 1986, several weeks after the overthrow of Jean-Claude

Duvalier (Baby Doc), who succeeded his father Francois Duvalier

(Papa Doc) in 1971, thirty-thousand women, represented by over

fifteen women’s organizations, assembled in Port-au-Prince to

demand their inclusion in the newly formed democratic Haitian

government [35]. In fact, theirs was the first demonstration

following the overthrow of the Duvalier government. Haitian

women were, as Myriam Merlet remarked, “[Revolting] against

exclusion. The country was being remade and we didn’t want it

to be remade without us ‘nou pa t vle peyi a ta refet san nou’ [36].

Grassroots pressure led by women’s organization in the 1980s

led to new provisions for strategic gender needs. The Haitian

Constitution in 1987 established new articles related to gender

equality. Articles 16, 17 and 18 of the 1987 Haitian Constitution

define citizenship as “the combination of civil and political rights …

‘all Haitians regardless of sex or marital status, who have attained

eighteen years of age, may exercise their political and civil rights’

…‘Haitians shall be equal before the law, subject to the advantages

conferred on native-born Haitians who have never renounced

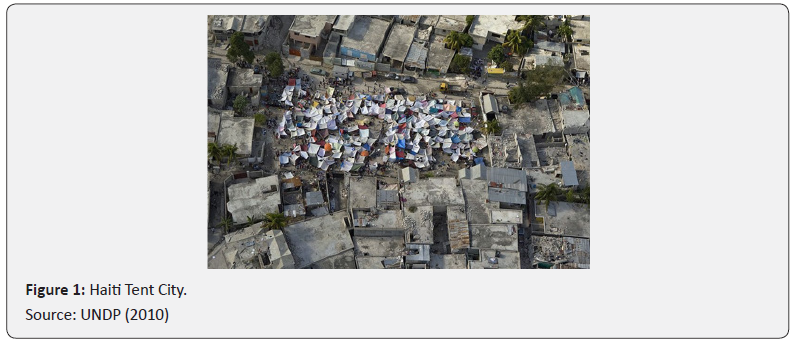

their nationality’” [37]. In the early 1980s, women’s groups grew

alongside the Haitian government transitioning from dictatorship

to democracy, representing a cross-section of goals and interests

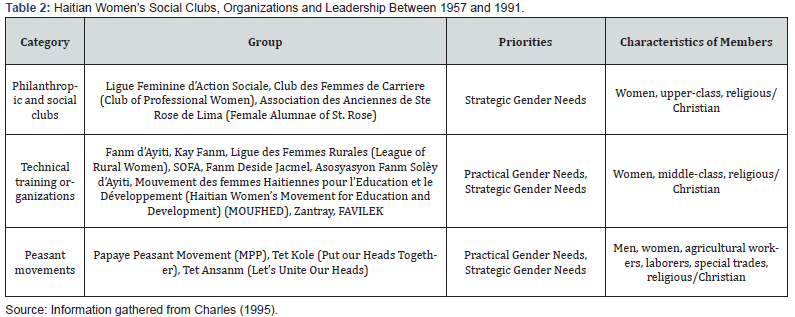

related to advancing women’s rights, housing, education, and

workplace equality (Table 2). Some traditional women’s clubs, such

as the Ligue, the Club des Femmes de Carriere (Club of Professional

Women) focused on philanthropic efforts to raise awareness on

promoting gender equality in the workplace and higher education

[33]. Other groups, such as Fanm d’Ayiti, Kay Fanm and Ligue des

Femmes Rurales (League of Rural Women), focused on practical

gender needs, or “survival issues,” such as food and shelter. There

were more groups like the Association des Anciennes de Ste.

Rose de Lima (Female Alumnae of St. Rose) that offered a range

of services that met both strategic and practical gender needs

like training centres on healthcare for women and children, and

education services for the poor [33]. Additional women’s groups

that were active between 1987 and 1991 included associations

like SOFA, FAVILEK, Fanm Deside Jacmel, Asosyasyon Fanm Solèy

d’Ayiti, Mouvement des femmes Haitiennes pour l’Education et le

Développement (Haitian Women’s Movement for Education and

Development) (MOUFHED). These organizations soon coalesced

into a powerful lobby in Haitian government. In 1990, the Lavalas

Movement, the party platform for Haiti’s first democratically

elected President, Jean-Bertrand Aristide, received the support of

many women’s organizations [33]. Eight months after Aristide’s

election though, a military-led coup d’état in September 1991

overthrew his presidency [10]. The women’s organizations that

once flourished alongside the fledgling Aristide presidency and

promises from the 1987 Haitian Constitution, quickly descended

into turmoil. After the 1991 coup, paramilitary forces targeted

organizations that promoted gender equality, burning down offices

and destroying homes of suspected Aristide sympathizers [33].

In 1999, the UN Special Rapporteur on Violence Against Women,

Radhika Coomaraswamy observed that “following the military

coup d’état, Haitian women continue to suffer from …‘structural

violence’, targeted at the most vulnerable and poor…between

November 1994 and June 1999, the Ministry of Women’s Affairs

and Women’s Rights registered 1,500 cases of girls between the

ages of six and 15 who had been the victims of sexual abuse and

aggression” [38]. In 1994, backed by a United Nations Security

Council Resolution, Aristide returned to Haiti as president and

established the Ministry for the Status of Women and Women’s

Rights (MCFDF) (Ministry of Women’s Affairs) to address the

socioeconomic status of women in Haiti. In alignment with the

1995 Beijing Declaration, the MCFDF designed the following

platform: “Conceiving, developing and implementing a policy of

equality between men and women based on dissemination of the

gender perspective or analysis of social relations between men

and women… Boosting the political role of the MCFDF within the

State apparatus… Taking specific steps to promote and defend

women’s rights.” [19] Plans for a gender-based assessment of

budgets and expenditures were also in progress under the MCFDF,

alongside campaigns for more women in elected office. However, a

second coup in 2004, sent Aristide permanently into exile in South

Africa, and left MCFDF close to dissolution. In the years after the

2004 coup in Haiti, there was a resurgence of violent attacks on

women and girls. Reports published in The Lancet estimated that

between February 2004 and December 2005, 19,000 per 100,000

girls were raped in Port-au-Prince [39].

State Violence and GBV

GBV as an instrument of pacification campaigns, state conflict,

and warcraft has long been part of country rebuilding and

wartime narratives. During the “Rape of Nanjing” between 1937

and 1938 for example close to 20,000 women reported being

raped in China. Janjaweed militias in Sudan have commanded

gender-selective killings of millions since the early 2000s. In

Brazil, military occupations of favelas Complexo do Alemão and

Vila Cruzeiro under “pacification police units” leading up to the

World Cup (2014), have led to thousands of unreported deaths,

rapes, and kidnappings. On GBV and state violence in Haiti,

Duramy’s [40]. extensive study found that the effects of French

colonization and slavery could still be felt in the country—as skin

color, dialect, gender, and property ownership play a significant

role in exposure to and experiences of violence, starting at an

early age. It is with great difficulty though that the experiences

of GBV survivors, men, women, and children, are accounted for in

tribunals, commissions, or peacekeeping operations—not for lack

of technical expertise on the part of mediators, activists, and other

practitioners, but for lack of political will. Gender-responsive

planning in state development has occupied a marginal role

in war tribunals, economic development, and state planning,

because it often calls for perpetrators of GBV, and other corrupt

and incompetent officials to face prosecution, exile, or sanctions.

Often, these perpetrators are politically well-connected or hold

military rank.

At a 1986 meeting on the status of Haitian women, Haitian

human rights activist and scholar Suzy Castor declared: “During the

long political life of Haiti as a nation, the contributions of women

to the struggles against the oligarchy and for democracy were

significant. Yet, their political roles have not been recognized. Like

all the other ‘subalterns’ their history has been obscured. There is

an historical erasure of [woman’s] condition” [33]. This erasure is

intentional, owing to the legacies of postcolonialism, neoliberalism,

and the culture of foreign aid dependency in Haiti and the rest of

the Global South. Haitian history, in its ebbs and flows, has seen

surges and declines in the visibility and participation of women

in society and economy. With limited mechanisms to predict or

even forecast natural disasters, pandemics, and armed conflict,

greater attention must be paid to equity, instead of pre-emption

in state planning. Equity in public policy administration and

practice would resemble government bodies adopting methods

to redress grievances while strengthening laws for accountability

and transparency. Paul Collier’s Bottom Billion [41] and Dambisa

Moyo’s Dead Aid [42] are two influential works that have shaped

debates on equity, paternalism, conflict, and global governance

over the past decade [43-52]. Collier maintained that many

developing countries fall into the “conflict-trap,” where political

instability and violence from domestic coups foster corruption;

while Moyo specifically denounced the complacency of African

leaders, who for years neglected investing in domestic financial

markets and civil society, instead relying on humanitarian aid to

resolve national crises. Gender-responsive planning thus presents

as an opportunity to integrate equity into law and state practice to

strengthen community resiliency in times of conflict and distress

[53-65].