Archaeology & Anthropology - Juniper Publishers

Abstract

The aim of this paper is to show some examples of the attitudes towards the burials and afterlife both in general and specially in the case of the nobles and the kings in the 10th century. One of the main questions of this research is to answer how Junius 11 can help to understand views about afterlife in late Anglo-Saxon England, but in a practical way, connected with the afterlife and highlighting the funeral practices. Since there are more evidence of funerary evidences that survived until today from the aristocracy, especially the kings, the main samples of the tenth century are the kings’ tombs, especially the house of Wessex and kings of the Anglo-Saxon England. New Minster in Winchester refoundation seems to have connections with the main concerns about the places where the Wessex kings were buried. The kings were in the top of the list of the privilege of ad sancto based on the hierarchy of social status that is be buried in the holy ground of the churches or monasteries in Anglo Saxo England. Even tough, it is difficult to measure who decided where the dead kings would be buried [1].

Research Article

One question necessary to mention, but not fundamental, it is the idea of purgatory. Le Goff [2] claimed that before the twelfth century there was not consistently belief in purgatory, challenged theory for some authors, as for example in Anglo Saxon England there is some authors that talk about purgatory or something similar more than only heaven and hell in afterlife: Bede, Boniface and Ælfric [3]. There are also the two Junius anonymous homilies: Oxford Bodleian Library, Hatton 114 and Oxford Bodleian library, Junius 85/86 also only mention two possible final destinies to the souls in the afterlife [4]. In an all those examples there are similarities and differences in the approach of heaven and hell but the focus of this paper is to understand the attitudes towards the kings or nobility tombs. Although, in most of Anglo-Saxon writings there is no clear mention about the space of the purgatory, but only heaven, hell and earth (that includes earthly paradise). Another subject that connects vision of the afterlife is the rituals made for the sick people that aimed help the soul of the person to go to the right sphere, to heavens. Most of then found in the Anglo Saxon England from tenth and eleventh century, especially in the southern England [5], where the center of political power was being built by the House of Wessex in the tenth century.

Before going to the burials of the noble people, especially the kings, it is noteworthy the connection of the heathen burials, or prehistoric with the monstrous, initiated in the 8th century by the Christians and possible to trace in the writings. This explains in the late Anglo-Saxon locations for death penalty of criminals on those monuments or historical ritual places [6]. In the eight century the Anglo-Saxons converted to Christianity began to use the Christian religion to stablish an effective power over their territories. The cemeteries from the age before the Anglo-Saxons cemeteries were chosen not only as burials, but as settlement, and even the architectural construction of the halls was modified by those changings: Prehistoric monuments and monument complexes were used not only for burial but sometimes as locations for settlement as well. (…) A changing style of hall also suggests an increased investment in elaborate, large buildings, and the introduction of restricted and bounded areas with fenced enclosures that, although not confined to these sites, served to demarcate and shape space perhaps even regulating access and movement [7].

There were also an increasing of the number of corporal punishments in the early tenth century, especially after Athelstan laws and a clear limitation of possibility to appeals to the king of appeal to king mercy [8]. This might show how the house of Wessex aiming to control the society and create the Alfredian project of a unified Anglo-Saxon England. About the afterlife according to Peter Brown, Western Christianity left behind between 7th centuries a more physical notion of afterlife in favor of a new one more based on the soul punishments [9]. The monumentality reflected the new era for the elite: Planning and structured layouts and larges enclosures with elaborate gateways are features present at Cheddar, Goltho, Steyning, and Little Paxton. The visual approach to such structures is suggested to have been an important factor in their design: the entrances and enclosures used as a means of framing the buildings. (…) Ritualized itineraries and more formalized royal activities of the tenth and eleventh centuries (see for example, the itineraries of Edgar, Edward and Æthelred) [10]. The tenth century is a moment of change of the Anglo-Saxon regions and the landscapes will reflect that. The old prehistoric sites will be reused by this elite while new buildings and burials will also be used as a tool to control not only the real life, but the afterlife of the Anglo-Saxons. As architecture plays a very important role in Junius 11 Art.

The Endowment and Reformation of New Minster of Winchester is a culmination of a process of tension where the West Saxon kings claimed to be the king of the Anglo-Saxons, and their most important tool was the church and all the imagery about kings brought up by the Christian Bible, especially the Old Testament. The sovereignty of the Rex Anglo saxonicus was assured and repeatedly proven by the support of the church and materialized by the construction of the New Minster in The kings who were more inclined to pursue with more tenacity the project created by Alfred of a united Anglo-Saxon England tendentially were Edward the Elder, Æthelstan and Edgar. Edward law code are seen as an extension of Alfred’s, which they both appear before With Edgar came a revived imperial vision and a return to early years saw a reaction against The Refoundation of the New Minster can provide access to the views about seminal and intrinsic nature of power and buildings in Anglo Saxon England. The New Minster was used as a tool to reassure their power as king: Winchester was included in the Burghal Hidage (temp. Edward the Elder) as a fortification rated at the highest assessment of 2400 hides. It has been suggested that the royal court may have settled there towards the end of Alfred’s reign. At least from this time, it probably took some political administrative and economic functions away from the exposed coastal lines trading-centre and royal villa of Southampton. Although the latter remained of importance both to the West Saxon economy and to shrivel government, Winchester began to advance to national significance. In this context, the foundation of the New Minster by King Edward the Elder and his advisers (…) may been seen as a political action, underlining the king’s power in the refortified borough as against the bishop or some of the leading citizens may have been at times out of favor with the king, due to dynastic politics, the city remained of crucial importance to the southern part of the kingdom, first of the Anglo- Saxons and later of England [11].

Even though happening later is not randomly how an episode of a plot against monks and the consequences inserted in the records of Refoundation of Winchester Minster in 996 is told evocating the same ‘story’ told in poem Genesis from Junius 11. It is remarkable how the highlighted aspects of poem and drawings are retold here. Apparently, it seems not connected, but the plot against those monks resemble the plot of Lucifer against God, and the object of desire of both are materialized in the right of the monks in have their monastery.

ix. CONCERNING THE ANATHEMA ON THOSE WHO PLOT

AGAINST THE MONKS.

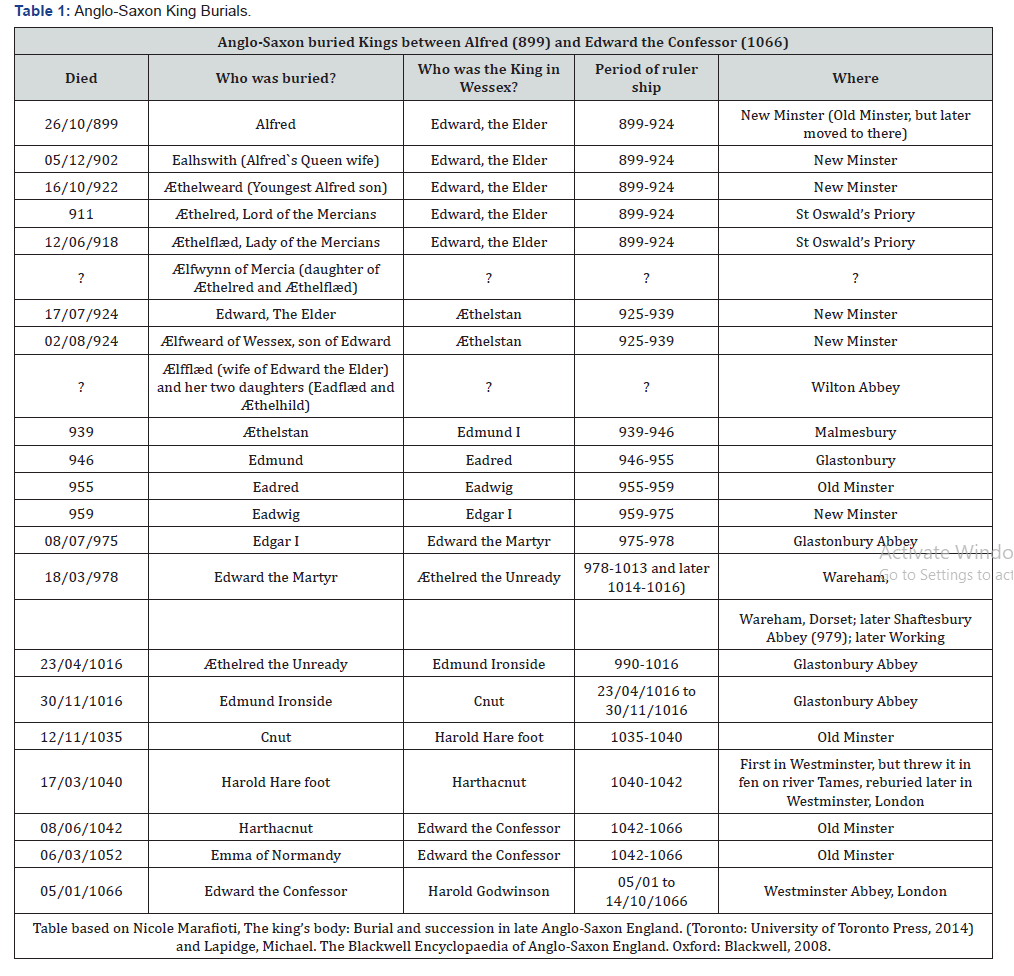

The identification of the traitors against the monks with the rebel angels shows how the narrative of fall of Lucifer was deeply connected with this historical moment of rebuild the Kingdom (as England) and the reformation itself. And this episode might show the resistance of the ones who have not accept the new spiritual and political directions of the late Anglo Saxon England. This episode among the others new elements might have been the perfect cultural and social environment that motivated the artistic choices behind the project of Junius 11. Also, there is a connection between the Endowment of the New Minster in Winchester and the burials of the nobility and the kings from the house of Wessex as we can see in the Table 1 in the annexe. Apparently there was an connection between times when the ruler has a compromise with the Alfredian idea of a unified Kingdom of England and the period of a fragmentation where Wessex and Mercian have had some territorial conflicts and this idea of unified England was not put as a priority by the King and his court, kingdom of Eadmund I (939)-9946), Eadred (946-955) and Eadwig (955-959). Alfred brought the body of his father Æthelwulf to Winchester from Steyning in Sussex. And as said before the New Minster was part of his plans for Winchester. As we can see all the noble during Edward the Elder (899-924) and Æthelstan (925-939) were buried in the New Minster.

Modes of royal burial varied with the political needs of each generation. The Tenth century was characterized by intradynastic, West Saxon succession. From 899 through 1013, every ruler of England was a patrilineal descendent of Alfred the Great, with each king succeeded by his brother, son or nephew [13]. There is a pattern, when the ruler was someone who prioritized the Union of the Anglo-Saxons as England as a unified kingdom, the dead noble people were buried in the new Minster, that is the ruler ship of Edward the elder (899-924), and Æthelstan (925-939). In the meantime, between 939-959, during the ruler ship of Eadmund I (939)-9946), Eadred (946-955) and Eadwig (955-959) as kings of Wessex, there was some troubles in Mercia to accept those kings as their ruler, and they seem to be no to worried about that as project as their predecessors. It is remarkable, given this context the most prominent site as king`s grave was Old the Old Minster], that royal burial shifted away from Old Minster in the tenth century. This move was initiated by Edward the Elder (r.899-924), who opened his reign by building a large new church, known as New Minster, next door to Winchester`s mother church. The king intended his foundation to supersede Old Minster as the kingdom premier royal burial place, but the mausoleum faltered after Edward`s own death; only one later Anglo-Saxon ruler, Eadwig (d. 959), would be entombed there` [14].

But with Edgar, both ideas of a unified England as one kingdom and the New minster as important place as burial of noble and the kings came back to centre of the stage. And more than this, there is the idea of reformation of The New Minster as symbol of this moment. The New Minster as tool for Edward the Elder to assure his legitimacy as new king of Anglo-Saxons: Æthewold`s interest in his father`s resting place might be attributed to convenience, were it not for the fact that Edward began cultivating his own father`s body at precisely the same time. Edward, however, pursued a more ambitious message than his cousin. While Æthelwold could revoke his father`s seniority as ruler of Wessex, Edward portrayed Alfred as the founder of an all-encompassing Anglo-Saxon kingdom, rendering Æthelred`s superior position within the West Saxon royal family a moot point. The concept of a cohesive Anglo-Saxon nation was rotted in Alfred`s own rhetoric - among other innovations, he was the first West Saxon ruler to be styled rex Anglorum Saxonum in his charters - but Edward`s posthumous celebration of his father`s body and memory helped cement this ideology [15].

The management of the AngloSaxon kingdom in the 10th century was perfected for a better control of the territory for such kings as Edward, Athelstan and Edgar: The Basic functions of the West Saxon Hundred unit can all be found as features of the landscape prior to the tenth century and it appears likely that earlier social and political institutions were re-shuffled at this time. I tis evident that the entire administrative machine was tightened up and regularised from the reign of Alfred, but increasingly so during the tenth century reigns such as Edward the Elder (899-925), Æthelstan and Edgar [16]. The ordinances of Edgar show that worrying about the administrative regional powers, a worrying meaning to make uniform the procedures through the Anglo Saxon-England. That show a new moment of the management of the kingdom: In the Danelaw areas the equivalent unit to the hundred was the wapentake. The word “wapentake” is derived from the Old Norse vapnatak, which refers to the brandishing of weapons in consent in an assembly [17]. In the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle in the entrance for the year 975, there is the information how Edgar was consecrated in Bath seeking remember the Glories of the Roman Empire, and the possibility of being called King of the whole island.

975 Her geendode eorðan dreamas Eadgar, Engla cyning, ceas him oðer leoht, wlitig 7 wynsum, 7 þis wace forlet, lif þis læne. Nemnað leoda bearn, men on moldan, þæne monað gehwær in ðisse eðeltyrf, þa þe ær wæran on rimcræfte rihte getogene, Iulius monoð, þæt se geonga gewat on þone eahteðan dæg Eadgar of life, beorna beahgyfa. feng his bearn syððan to cynerice, cild unweaxen , eorla ealdor, þam wæs Eadweard nama .7 him tirfæst hæleð tyn nihtum ær of Brytene gewat, bisceop se goda, þurh gecyndne cræft, ðam wæs Cyneweard nama. Ða wæs on Myrceon, mine gefræge, wide 7 welhwær waldendes lof afylled on foldan. Fela wearð todræfedgleawra Godes ðeowa; þæt wæs gnornung micel þam þe on breostum wæg byrnende lufan metodes on mode. þa wæs mærða Fruma to swiðe forsewen, sigora waldend, rodera Rædend, þa man his riht tobræc. 7 þa wearð eac adræfed deormod hæleð, Oslac, of earde ofer yða gewealc, ofer ganotes bæð, gamolfeax hæleð, wis 7 wordsnotor, ofer wætera geðring, ofer hwæles eðel, hama bereafod. 7 þa wearð ætywed uppe on roderum steorra on staðole, þone stiðferhþe, hæleð higegleawe, hatað wide cometa be naman, cræftgleawe men, wise soðboran. Wæs geond werðeode Waldendes wracu wide gefrege, hungor ofer hrusan; þæt eft heofona Weard gebette, Brego engla, geaf eft blisse gehwæm egbuendra þurh eorðan westm [18].

After that Edgar travelled according to The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle to Chester, another ancient Roman stronghold, symbolically building his supremacy over the whole Great Britain. The use of a ship to go there brings the idea that Albion, Britannia is an Island. His travels by ship fact or post fiction reveal that conscious factor. He was not the first king of nobleman to use the ancient monuments as a frame for his royal activity and connect himself with the past of the Roman Empire. But with Edgar the theatrical reached the maximum peak until that moment: There are implications here of far reaching vision in which the ancient , whether prehistoric or Roman, and perhaps the physical remnants and memories of the Pre-Christian Past , were being drawn upon in a variety of ways to create a network of theatres and arena s in which power and authority were articulated and enacted. (…) It is thus fitting to end with Edgar, a master of spectacle and theatricality. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle records that in 973 (ASC (A) Edgar, ruler of the English, was consecrated `as king in a great assembly` at Bath [19].

King Edgar had a great interest in the activities of Continental Europe and look for ancient sites and use the, as symbolic ritual [20]. Edgar was also a master of the theatrical politics. But as said before, his kingdom is the result of a process initiated with King Alfred, the idea of an only one nation of English people. The ritualization and symbolic new usage of the Roman past. Cultural topography of emerging Angle-land was to be found in texts of Christian Anglo-Saxon culture, is allegorized form. The new literary monumentalizing in intent, seeking as it did to control the narrative of land, ancestry and identity through written text in which engagement with the physical land became increasingly symbolic and relative to a more transcendent spiritual cosmos and polity [21].

As in Junius 11, the ancient monumentality of the roman columns and the roman portraits were reused in the Christian context to show to establish the power of God as king of the Heavens, the same process has been made by the refoundation of the New Minster in 964, with the assistance of Æthelwold, the new bishop. His predecessor was buried the New Minster. Given Edgar interest in renewing the new Minster, it is possible to believe that he decides to bury his brother there, Eadwig, aiming to reactivate the project of New minster as a King mausoleum. In the new Minster refoundation charter, written in 966, the preface is very similar to the beginning of Genesis poem of Junius 11, as start with the fall of the rebel angels: EADGAR REX HOC PRUILEGIUM NOUO EDIDIT MONASTERIO AC OMNIPOTENTI DOMINO EIUSQUE GENITRICI MARIE EIUS LAUDANS MAGNOLIA CONCESSIT. ΧΡ OMINIPOTENS TOTIUS MACHINAE CONDITOR inefabili pietat uiuersa mirfice moderator que condidit . Qui coaeterno uidelicet uerbo quaedam ex nichilo edidit quaedam ex informi subtilis artifex prpagauit materia. Angelica quippe creatura ut informis materia nullis rebus existentibus diuinatus formata luculento respelnduit uultu. Male pro dolor libero utens arbitrio contumacy arrogans fastu creatori uniuersitatis famulari dedgnans semetipsum creatori equiperans aeternis baratri incendiis cum suis complicibus demersus iugi mertio cruciatur miseria. Hoc itaque thmate toius sceleris peccatum exorsum est [22]. It starts very much alike with the genesis from Junius 11, and even the fall of the Lucifer and his rebel angels. And also, the text talk about how this sin leads to others worst sins, following the same narrative of Junius 11 in image and text.

The prominence of Edgar and the fact he is the first King to be picture in a throne is another evidence of his agenda of controlling the spaces of power, supernatural or not altogether with the Benedictine Reform. King Edgar was able to control spread his control over the church itself [23]. Then during the 10th century there was a long process of searching by the nobility to look for the monumentality, to the past of old or prehistoric burials aiming to open their claiming to the power. The House of Wessex started in project with Alfred but only in real life with Edgar this project reached his peak of successful through the theatrical power played by Edgar using all the Christian recurrent elements present on Junius 11. It is impossible claim that Junius 11 was totally created during Edgar`s kingdom (959-975) or during the Refoundation of the New Minster (964). But after all the evidences here presented it is possible to highlight how the tombs were used by the kings of Wessex to reassure their own power throughout the whole England, and how the afterlife will be the centre theme of art productions (e.g. British Library Junius 11).

To Know more about Archaeology & Anthropology

Click here: https://juniperpublishers.com/index.php

No comments:

Post a Comment