Social Sciences & Management studies - Juniper Publishers

Abstract

This case study examined 303 undergraduate students

enrolled in seven traditional face to face courses who were offered the

opportunity

to self-select into one of four blended modes of instruction. Students

could select face to face (F2F) intervals of 90% (almost exclusively in

the

classroom) to 70%, 30% and 10% (almost exclusively online with the

exception of final exams). Findings suggest that students preferred a

blended 70:30 face to face instructional delivery. Motivating factors

including but not limited to the age of the learner, employment,

flexibility

and convenience, the number of courses a student is enrolled in, whether

a course was an elective for their degree completion and commuting

distance were all found to be significant factors in predicting a

student’s self-selection of instructional delivery.

Keywords: Online; Blended; Hybrid; Instructional delivery; Face to face; F2F; Self-selection; Grade attainment

Introduction

The COVID19 coronavirus led the World Health Organization

(WHO) to identify a global pandemic in 2020 which forced the

closure of thousands of schools, colleges and universities across

the United States and abroad [1]. As the WHO reports, this is the

first time in recorded history where “technology and social media

are being used on a massive scale to keep people safe, productive

and connected while being physically apart” [1]. This has led

colleges and universities across the world to scramble to attempt

to complete courses online without face to face community spread

in the classroom. This global pandemic [1] has forced instructors

to adopt radical approaches to complete their courses online

potentially neglecting their own unique outcomes but rethinking

how their courses can be implemented in the future. This article

offers a glimpse into how self-selection of instructional delivery

could assist in delivering courses in the future.

Academic learning within post-secondary institutions has

traditionally been face to face (F2F) teaching instruction. The

scholarship of teaching and learning has always encouraged and

promoted the use of best practices determining what works, what

doesn’t and what is promising [2-6]. However, there is no one

size fits all, universal method of instruction simply because each

instructor is unique in their own delivery [7-9]. Every instructor

has their own unique outcomes for their coursework (Singh,

2006) and this certainly varies based on class size [10], lecture

versus seminar courses [11-13], basic versus applied courses

[11,14] and by discipline [15]. As such, governments, post-secondary institutions and

students/ consumers have begun pondering whether online

programming is more effective than blended or face to face

engagement in the classroom. As such, the timing of this study may

not be more appropriate. How do universities and faculty react

to a changing online environment and how might students wish

to proceed in an online/hybrid environment? What are student

motivations for taking blended coursework and furthermore,

what might be the most appropriate level of engagement

that ensures strong performance outcomes? This case study

focuses on approximately three hundred students within seven

undergraduate courses at a medium sized liberal arts midwest

American university.

Literature Review

Research indicates that online and blended courses are reliable

and valid methods of course delivery [3,5,16,17]. Similar to face

to face course instruction, the evidence of the efficacy of online

courses is mixed. For each study that suggests online instruction

is similar or as effective as traditional classroom instruction

[2], there are also studies to the contrary [18]. The reasoning is

simplistic. There is a plethora of course deliveries available for

instructors from the extremities of traditional F2F instruction to

no F2F interaction at all. A meta-analysis by Zhao & Breslow [19] reported that evidence

is mixed in terms of the efficacy of blended versus traditional

and online learning deliverables. The lack of comparison groups,

low sample sizes and the differentiation of modes of delivery

[19-21] impacted the efficacy of the 45 studies examined. The

meta-analysis concludes that students who enroll in hybrid

learning “performed modestly better” than those enrolled in F2F

interactions [21]. However, there is very little research to suggest

how student self-selection can impact their chosen instructional

delivery. Often instructional delivery is forced on students and

they do not have the opportunity to select what might be in their

best interests. The purpose of this study is to build on what we

know, what we don’t know and what is promising highlighting selfselection

within differing/varying intervals of F2F interactions.

The Sloan Consortium has adopted a scaled form of online

learning delivery based on the percentage of content delivered

online [2]. The lowest level of content delivered to students is

denoted as web supported delivery; where online instruction is

less than 30% online and focuses specifically on online content

and internet sourced works. This could range from using

selected readings that are available online or within a digital

library consortium to the adoption of online readings developed

by book publishers. Alternatively, the higher extremes of 80%

and above are categorized as online. This categorization could

be the implementation of entire textbooks and performance

measurement outcomes. Hybrid or blended learning is determined

to be within the mid-range of 30%-70%. This is where there is

an inclusion of more digital content with an emphasis on some

F2F lecture or seminar time (without it being diminished almost

entirely).

The motivations for students selecting online and/or blended

programs are based primarily on three priorities: convenience,

flexibility in programming and managing their educational

attainment with their employment [22]. Jaggers [23] reported

that 80% of participants who selected online courses in Virginia

did so due to time conflicts with employment (50% being full

time employment). While many studies point to the need of

flexibility of employment [23-25] when selecting courses, very

few include volunteerism and/or internships. Often students will

be supplementing their educational attainment with volunteer

experience and/or internships that also affect their time

management and flexibility, yet it is not studied with much rigor.

However, there is also the possibility that other demographic

variables and motivators may be able to predict why students

select online or blended learning environments.

With a sample of nearly 650 undergraduate students, Harris &

Martin (2012) reported that students who were older were more

likely to enroll in a fully or mostly online course, while those within

the 18-22 range are more likely to remain traditional classrooms,

likely due to being on-campus already (being part or full time).

Older students have been found to be more likely to engage with

online materials [26,27], enroll in online courses [28] while also

exploring and identifying new content [29]. Chyung [27] found that

non-traditional and older students were more active on discussion

boards than their younger counterparts, while also boasting

more content-based narratives. Studies have also suggested that

the older the student, the more likely they consciously examine

material leading to better performance [27,30]. There is also a likely correlation that those students who are

older are more likely to be employed, have a significant other,

dependents and/or employed and less likely to be on campus

[22,31,32]. Jaggers [23] reported that 30% of participants who

selected online courses in Virginia did so due to child care time

conflicts. Therefore, we should not assume that age is the strongest

predictor, but rather a significant predictor of determining

whether a student considers a traditional, blended or solely online

course.

Boysen et al. [33] have reported that nearly half of students

can feel victimized by instructor bias, either implicit or explicit. As

such, instructor bias can be reduced if course delivery is managed

in an online environment rather than face to face. Those who

self-identify as visible minorities (whether through sex, gender,

race, ethnicity) or who may have language barriers may feel

more comfortable taking courses outside the classroom, where

there is less likelihood of bias. Ruling out ignorance, prejudice

or racism certainly should not be underestimated (via either

implicit or explicit bias). The availability of an online course or

more blended coursework mitigates this potential bias [34,35].

Conaway and Bethune have reported that White instructors had

shown an implicit bias towards African American names more so

than instructors of other ethnicities. Therefore, those students

who may self-identify of a different sex, gender, race, ethnicity

and/or even speak a less prevalent language than English could be

more vulnerable to bias. However, as Jagger [23] suggests, those

speaking foreign languages may not be as proficient in online

environments that are generally in English. Perhaps, a universal

design offering easy language translation could reduce these

issues (which are already available online). However, it is often

difficult to ascertain how prevalent demographic variables are in

determining self-selection because it is likely due to unobservable

factors which are likely situational and can change based on

individual student circumstances. As Xu & Jaggers [36] suggest it would be useful to compare

representative online courses to traditional face to face courses.

Xu & Jaggers [37] examined 24,000 students across 23 community

colleges in Virginia concluding that students performed

“significantly worse in online courses in terms of both course

persistence and end of-course grades” (2011:375). This is further

corroborated after they examined 34 colleges in Washington State,

Xu & Jaggers [36] report that an online format had a significant

negative impact on a student’s course persistence and grade

attainment (2013: 54). This study hopes to build on their work

to control for those motivating factors including influences on a

students’ course selection of instructional delivery, employment,

volunteerism and educational motivation like one’s field of

study and grade expectations/ attainment. Furthermore, this

study further accentuates the need to account for “unobservable

underlying student self-selection [which] may underestimate any

negative [… or positive] impacts of the online format on student

course performance” [36].

Methodology

The participants of this study were chosen from seven

traditional undergraduate courses offered within a midwestern

American liberal arts university. Three hundred and twenty-two

undergraduate students, initially unaware of any instructional

self-selection study. enrolled in a typical sixty student maximum

face to face 200-level required course in criminology/ criminal

justice. The study sample began with 334 eligible students enrolled in

seven criminology courses during both fall and spring semesters.

Twenty-two students were removed from the study having

dropped or withdrawing from the course throughout the semester.

An additional nine students were removed from the study for

not having completed the pre-test (n=5) and/or post-test (n=4)

survey. Therefore, the sample size for the purpose of analysis was

303 participants. Each of the seven undergraduate criminology courses were

offered over a sixteen-week semester cycle encompassing 34

one-hour blocks of class time. The course was designed with the

specific purpose of exploring the nature of crime and theories

associated with offending. The course was predicated on utilizing

a text that could be offered in both print and online versions.

Microsoft power point modules were also used to ensure that

additional resources were included in the course to ensure the

retention of key concepts, inter-connectivity with the text and

any outside resources. Students would be expected to read the

required text for the course in addition to supplemental technical

reports, peer reviewed articles and online audio-visual clips.

Each course was designed to ensure consistency across

performance measurements. Performance measures included

three examinations (75% of a final grade) and three assignments

worth 10%, 5% and 10% respectfully. The three examinations

were proctored in class and were similar in questions and

rigor. Examinations were designed for reading comprehension,

retention and application of information. Three assignments

could easily be related to course materials presented in class and

a student’s ability to identify other valid online sources (technical

reports and peer reviewed studies) to ensure connectivity and

engagement to the text and course content. Assignments were

designed with more emphasis on critical thinking and problem

solving (associated within experiential and student-centered

pedagogical approaches). Rubrics were clearly conceptualized

and operationalized within an online environment with drop-box

delivery systems. Ensuring systematic and consistent performance measures

were integral to ensure transparency, fairness and equity in

grading for all students in these courses. Transparency in grading

rubrics and performance measurement objectives would also

assist students in their initial choice of selecting instructional

delivery; further ensuring that blended or online delivery would

be no more or less difficult.

Maintaining systematic and consistent measurements

across

all seven classes ensured that there would be fewer disparities

in how the classes were taught. The study also attempted to

alleviate concerns that online courses would require more time

to grade engagement measurements. Therefore, no additional

instructional time was allocated to an online delivery system

that would not be present in a traditional course delivery. While

significant time and energy was devoted into developing these

instructional methods of delivery, no one group was asked to

do more rigorous work than another group. This simplistic

approach was adopted to demonstrate that instructors may not

need to compromise outcomes when developing new types of

instructional delivery that students could select. However, due to

the simplicity of the study, there were some obvious limitations.

Attendance and participation/ engagement would not be a

measurable outcome. Therefore, whether in face to face classes or

online, some common engagement techniques were not utilized.

Students were offered discussion boards, discussion threads and

online video conferencing as levels of peer engagement similar to

that of a traditional classroom setting. However. these modes of

engagement would not be used as performance measurements.

This conflicts with other studies such as Garrison & Anderson

[39] that argue engagement is important within online settings. How to

cite this article: Michael S.Student Motivations that Predict the

Self-Selection and Choice of Blended Instructional DeliveryAnn Soc Sci

Manage

0034 Stud. 2020; 5(2): 555659. DOI: 10.19080/ASM.2020.05.555659

Annals of Social Sciences & Management studies

Despite the lack of graded engagement, the use of office hours and/

or email for instructor feedback or assistance was still available.

This study assumed that offering more immediate instructor

feedback (Acton et al. 2005; Hill et al. 2013) was more important

than grading engagement as a performance measure.

On the first day of classes, students were asked to choose

or self-select into one of four types of instructional delivery

methods. This study conceptualized and operationalized four

instructional delivery systems as developed by Twigg [40] and the

Sloan Consortium [2] into different categories of hybrid/blended

instructional delivery: replacement (90:% F2F : 10% Online),

supplemental (70% F2F : 30% Online) and two emporium options

- 30% F2F : 70% Online and 10% Online : 90% F2F.

In selecting an instructional delivery mode, students were

offered four options. Utilizing a replacement model approach,

Twigg [40] articulates that some in class time can be replaced

rather than supplemented with online or interactive learning

activities. Using this model, 90% of the course would be delivered

face to face and 10% online. Within this 90:10 option, 10% of

course materials and assignment functions would be online with

students able to interact with one another in class or through

discussion boards. Over a sixteen-week semester with 34

instructional hours, 28 hours would be devoted to face to face

lectures, 3 hours devoted to 3 examinations and 3 hours devoted

to online learning. These three online classes would be used

to replace time in class devoted to written assignments so that

students could utilize reliable and valid sources of information

to supplement their written work. These classes were designed

around both experiential and student-centered learning strategies

while also ensuring compliance in reading comprehension and

retention of key concepts and themes (Chen et al. 2010; Stelzer

et al. 2010).

The second option, designated as a 70:30 blended option,

offered students 70% of the course within the classroom and 30%

within an online environment. Within this 70:30 supplemental

approach (inclusive of 34 instructional hours), 21 hours would

be devoted for face to face lectures, 10 hours initially designated

as face to face lectures would be substituted by 8 video-based

lectures and 2 hours of independent online readings. Three hours

were devoted to in class examinations. The 10 digital lecture

recordings would be made available through Camtasia software

within an online environment. Digital recordings of all instructor

criminology/ criminal justice lectures allowed for its simple reintroduction

at different intervals without revising content and/

or translation. Therefore, class-based discussions could still be

utilized and implemented within an online environment. Students could select a third option, denoted 30:70, where 30%

of the course would be delivered face to face and a larger majority

(70%) would be offered within an online delivery environment.

The emporium approach [40] offers students a replacement of

face to face discussions with more online deliverables including

more Camtasia lectures and collaborative peer discussions, if

students want to remain engaged. This approach offered students

more independence and flexibility outside the classroom. In

terms of instructional delivery, 3 hours were devoted to in class

examinations, 10 hours were allocated to instructional face to

face lectures with 21 hours of original lecture time replaced with

19 hours of digital Camtasia lectures and 2 hours of independent

readings.

To offer students even more selection, students were offered

the choice of a 10:90 instructional delivery. Similar to a very

traditional online delivery, 10% of the course would be delivered

face to face and 90% of the course would be instructed within

an online environment. This emporium model approach offered

students the most discretion and flexibility in their schedule

where 3 instructional hours were devoted to examinations, 3

hours for face to face discussions that were pertinent more to

assignments and examinations whereas 28 hours of instruction

was delivered online. Digital Camtasia lectures and tutorials were

utilized to replace all face to face lectures while discussion boards

and threads were also utilized as forms of engagement (but were

not graded). Symbolic of Twigg’s [40] modelling, there inherent design of

the course was to ensure that students were able to self-select and

choose their instructional delivery. As such, the study wanted to

ensure that students were generally satisfied with their selection.

Therefore, after the completion of the first exam (one month; 8

classes into the course), students could re-select an option that

they initially had not chosen. This offered each student more

flexibility if they felt the instructional mode they first selected

was incorrect. This buffet style approach [40] offered students

the ultimate level of discretion of their own learning environment

without revising any performance measures. This was also a

component of the study to ascertain whether students would

revise their original desired instructional method to something

more useful for that individual student.

In addition to selecting an instructional delivery model,

students were asked to complete a pre-test survey to attain baseline

data. A pre-test self-administered questionnaire was explained in

class and students were expected to complete the questionnaire

and their self-selection of class instruction within two days. The

questionnaire included demographic variables associated with

age, sex, self-identified race and ethnicity, language preference

and motivating factors which were explained previously in the

literature review. This pre-test questionnaire was supplemented

with validated measurements (attaining additional consent for

use of a student number) to ascertain each student’s educational

status (based on number of credits attained), a validated grade

point average, number of courses the student was enrolled in at the

beginning of the semester and their home address to determine

their proximity to the University campus.

Findings

As explained previously, the study sample began with 334

eligible students enrolled in seven 200-level criminology/

criminal justice courses within a liberal arts University in the

Midwest United States. Thirty-one students were removed from

the study for (i) having dropped or withdrawing from the course

or not completing their self-administered surveys. Therefore, 303

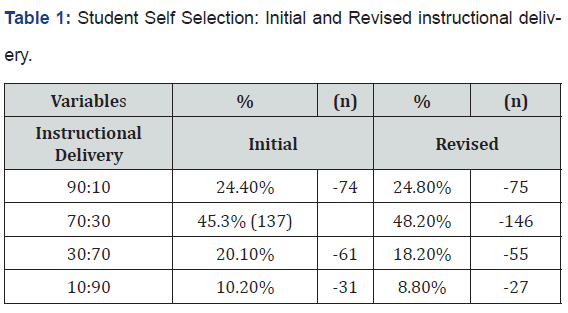

students were used for the analysis of this study. Table 1 below illustrates the self-selection of instructional

delivery that each student has chosen. As explained previously,

students initially chose their preferred instructional mode within

the first few days of the beginning of the course. However, each

student was also able to revise this choice at any time between

the beginning of the course and the first examination (one month

later).

When given the opportunity, a large majority of students

initially selected an emporium approach (as explained by Twigg

[40]). Nearly half of the seven classes of students (45%) preferred

the 70:30 blended option; giving them more flexibility than the

90:10 traditional course (24%) or the more online 30:70 blended

(20%) option. One in every ten students selected the almost

entirely constructed course where 90% would be instructed

online. However, the decisions of students became clear after one

month of the course had been completed. Of those 31 students who

initially chose the 90:10 option, four students re-selected to the

70:30 option. Of those selecting the 30:70 instructional delivery

(61 students), six students revised their decision with one student

returning to the most traditional instructional method and five

moving to a 70:30 mode of delivery. It was clear that students did

appreciate more of an emporium approach (64%) to traditional

(25%) or almost solely online (9%) instructional delivery. The

ten students who re-selected and/or revised their initial decision

all had said in some form that they wanted more opportunities

to interact with other students and/or attain more detail in

understanding key concepts and themes. It should be noted that

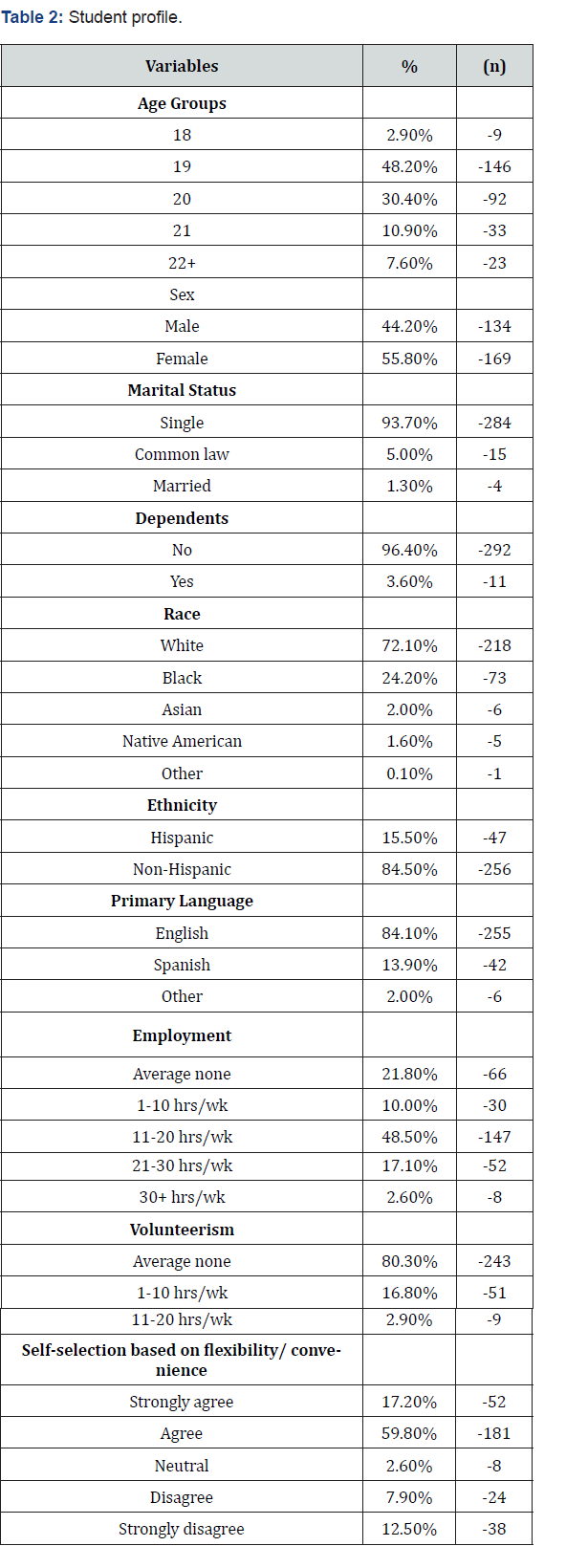

the revised selection options were used for further analysis. In addition to choosing their desired instructional delivery

medium, students were asked to complete a short open-ended

self-administered questionnaire at the beginning of the course.

Responses were relevant to establishing a baseline of data points

to understand the profile of the sample. Responses of the variables

of interest were coded to generate the appropriate values; as seen

below in Table 2.

The profile of the students studied would suggest this is

a typical, traditional 200-level undergraduate course where a

majority of students are young and progressing to determine

their career trajectory. In terms of age, a significant majority

(92%) of students who participated in the study were generally

21 or under, Similar to the University demographics, women

represented a larger percentage (55%) of the students enrolled

in the courses. Students represented in the sample are young,

single (94%) and are without children or dependents (96%).

Similar to the University’s student body demographics, the

majority of students self-identified as White (72%), a large

concentration of students self-identified as Black and/or African

American (24%). Furthermore, those who identified as Hispanic

were approximately 16% of the sample and typical of the student

body at the University where this study was conducted. English

was the primary language spoken and was not a limitation to this

study as all students had a proficiency in English despite 16% of

respondents suggesting English was their second language.

The open ended pre-test also encouraged students to

explain some of their current and/or situational factors that

may be impacting their self-selection of instructional delivery. As

denoted within the scholarship of teaching and learning research,

students are often employed and/or volunteering outside of the

classroom to supplement their career aspirations. Almost eight

in ten students in courses reported being employed at the time

of being enrolled in the course. A large majority of students

(58%) reported working part time while as many as 19% of the

students reported working over 20 hours a week in addition to

their coursework. A large percentage of students (80%) were not

involved with volunteerism and/or internships at the beginning

of the course. This is likely due to their workload in and out of the

classroom. A further question asked students to report whether

time flexibility and/or convenience would impact their decision

to self-select into a specific instructional method. Three-quarters

of students reported that they agreed (60%) or strongly agreed

(17%) that flexibility and convenience would have an impact on

their decision. These findings would substantiate the literature as

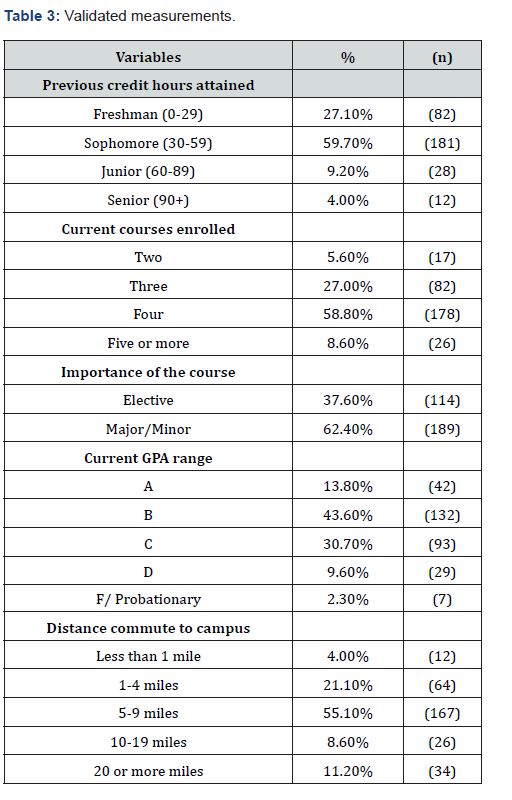

to why students may consider blended or online learning. In addition to the self–reporting of the students, it was also

important to attain other validated measurements. Student

consent to the study allowed for the use of their University student

number to access other variables of interest (Table 3).

Validated measurements of students were able to supplement

the knowledge attained by students while also ensuring more

validated measurements focusing on accuracy. As such, it

appears that these measurements validated the data that was

self-reported by undergraduate students in the study. Consistent

with the previous table, the ages of students and credits attained

matched to substantiate that students enrolled in the 200-level

criminology/ criminal justice courses were typically freshmen

(27%) and/or sophomores (60%), thereby not having significant

progress towards their degree. This would explain why a low

percentage of students may not be as active in volunteerism and/

or internships (as they are still deciding on their career path).

Furthermore, a large majority of students were taking larger

numbers of classes simultaneously. Less than 6% of the students

were taking courses on a part time basis while a remarkable 94%

of students were taking three or more classes (considered full

time employment). This is particularly troubling as nearly 8%

of the sample were taking the most courses allowed (without

permission) at five courses within the same semester. If we consider that nearly 60% of students are also employed part time

and another 20% of students are working over 20 hours a week,

this could be considerable strain on many students within the

sample. The relative importance of the course was another variable

of interest that is often not considered particularly pertinent in

the literature. Perhaps students who are more likely to engage in

a their designated career path (in this case criminology/ criminal

justice) feel that face to face course work might be more ideal

versus students who perceive the class as simply an elective (and/

or perhaps a class they simply have to complete their liberal arts

degree). A majority (62%) of the students enrolled in the seven

courses were utilizing the class as a chosen major or minor of their

study while 38% of students were taking the class as an elective

and/or general course (not having declared a major or minor in

criminology/ criminal justice).

Two variables of interest that are often self-reported and not

necessarily validated in the literature were two of the final variables

of interest. Preferring precision and accuracy, University Registrar

records report that a large percentage of students (74%) were in

the grade point average (GPA) range of a B to C. A lesser number of

students had an A average (14%) while one in ten students (11%)

were considered more high risk (having attained a D, F and/or

probationary score). The second variable of interest was meant

to assess and test the effect of commuting distance to determine

if a longer commute to campus had an impact on self-selection.

The University is considered more a of a commuter campus and

as such, the student data was supportive of this analogy. Three of

four students lived further than 5 miles from campus making the

commute particularly more time consuming. This study did not

address parking or public transportation. However, it appears

that a substantial percentage of students would require time to

commute as nearly one in five students commute over 10 miles

each way, as per their schedule (which is predominantly two to

three times a week) which could be five days a week. It would be

expected that the longer the commute, the more likely students

may select a more online based course. However, as illustrated

above, a majority of students are taking a full-time course load

so they may likely need to commute to campus for other courses.

This should be considered when considering self-selection. The following section examines how self-reported and further

validated motivating factors predicted a student’s self-selection of

blended or hybrid instructional delivery. Due to a lack of variation

in responses, several variables were unable to be included in the

multivariate analysis. This includes one of the dependent variables

(the 90% face to face to 10% online instructional delivery). For this

reason, these variables were excluded to ensure a reduced level of

error and multicollinearity. With a sample size of 303 students,

the data analyses attempted to control error and multicollinearity

with a tolerance level of 2 and a variance inflation factor of 4.0 to

ensure that data outliers would be removed from the analysis.

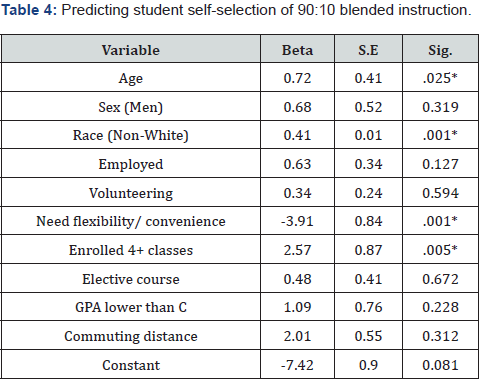

Table 4 below examines the predictive power of motivating

factors that influence students’ self-selection of rhe most

traditional form of instructional delivery where 90% of the

course is face to face with 10% of the course within an online

environment. This model was found to be statistically significant

(.001 with a confidence level of 95% with the p < .05 being

significantly different than zero). The motivating factors within

the model explained 36% of students selecting a 90:10 more

traditional instructional delivery (versus other delivery methods)

based on a Nagelkerke R Square. The regression reported a Chisquare

of 184.32 and a model -2 Log likelihood of 243.49 (with 10

degrees of freedom).

Findings suggest that while the model was good at predicting

a 90:10 delivery of course instruction, only four variables were

statistically significant at the .05 level. Those who were older were

more likely to take a traditional face to face instructional method

than a more blended or online approach. This is an interesting

finding as you would expect that the older a student is, the more

responsibilities they may have outside of taking courses at the

university. However, the limitation of the study is that the range

of the students who took this course was from 18 to 37. As such,

it may not be representative of students in their mid to late 20s

as a large percentage of students were below the median of 20.

Students who self-reported as non-White were more likely to take

a 90:10 delivery method than students who were White. While

race has been considered a variable of interest, it may be difficult

to determine why this could be the case in this model. The two most significant variables in the analysis

(based

on the Beta values) were those who did not require flexibility/

convenience and students who were enrolled in four or more

classes within the same semester. It appears that students who did

not require additional flexibility in their schedules were more likely

to take a 90:10 deliverable course. This is consistent with some

of the research that has been conducted. Furthermore, students

who were enrolled in four or more courses within that particular

semester (equating to 12 credit hours or more) were more likely

to consider a more face to face instructional delivery. While this

appears to contradict the idea of flexibility and convenience, this

finding could be a result of students having to attend other classes

on campus and therefore, simply chose to attend class because

they were on campus already. This finding would require further

research to substantiate.

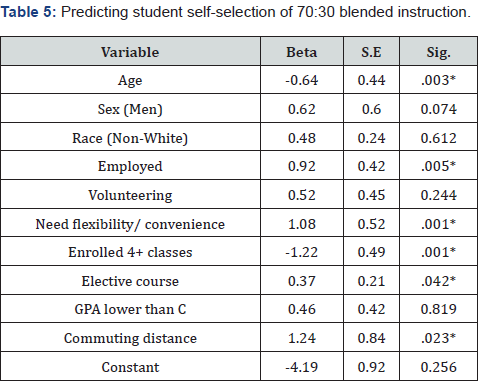

The Table below examines the strength of ten motivating

factors influencing students’ self-selection of the most prevalent

70:30 instructional delivery. In this mode of instructional delivery,

70% of the course is face to face and 30% of the course is available

within an online environment. This model was also found to be

statistically significant (.001 with a confidence level of 95% with

the p < .05 being significantly different than zero). The motivating

factors within the model explained 51% of students selecting a

70:30 instructional delivery based on a Nagelkerke R Square. The

regression reported a Chi-square of 244.81 and a model -2 Log

likelihood of 314.26 (with 10 degrees of freedom). It should also

be noted that three cases/outliers were removed from the analysis

to ensure there was no multicollinearity.

The model explained in Table 5 finds that half of the variables

of interest are significant when understanding a blended form

of instructional delivery (versus other modes of delivery).

Findings suggest that there is considerable differentiation as

to why students in this sample chose blended learning versus a

traditional form of instructional delivery (Table 4). Age remained

a significant demographic variable of significance. It appears that

the younger the student, the more likely they would enroll in a

70:30 blended instructional delivery of a criminology class. This

could be due to a number of other corresponding factors such

as comfortability of online environments or different priorities

(versus older students). More study would be needed.

Employment, or the more a student works per week was

found to be significant in determining if a student selected a 70:30

blended instruction. It also appears that other factors or a complex

set of factors is having the most impact on a student’s selection of

70:30 delivery. The Beta values above would suggest that the three most

significant motivating factors was the commuting distance of

students, enrollment of fewer than four courses per semester

and the need for flexibility/ convenience in their scheduling.

These variables of interest have all been found to be significant

in other research studies. In this particular study, it would appear

that the longer the commute a student has to the University

(from their primary listed address), the more likely they would

consider enrolling in a 70:30 blended instruction. This would also

correspond to the relevance of taking fewer classes and perhaps

not being on campus as often, providing them more flexibility

and convenience. As we know, most students will select courses

on particular days (Monday, Wednesday, Friday or Tuesday,

Thursday) rather than five days a week. It also becomes apparent

that students who take the course as an elective were more likely

to consider the 70:30 blended instruction than those students

who enrolled in the course to fulfill their major or minor liberal

arts degree requirements. Therefore, with a commuting distance,

higher levels of employment per week and convenience, it would

not be self-serving if students selected a traditional method

especially considering that they are taking fewer classes.

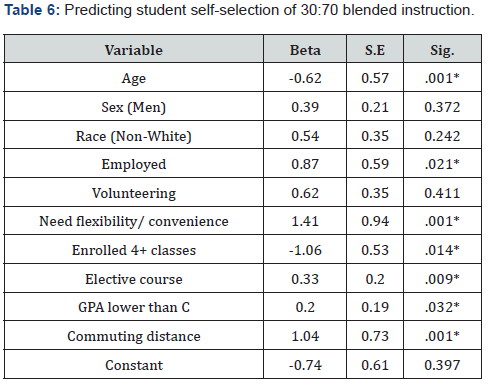

Table 6 illustrates the predictive power of ten motivating

factors that influence a student’s selection of a 30:70 blended

instructional offering (versus other instructional deliveries).

The model was found to be statistically significant at a .001

with a confidence level of 95% (with the probability < .05 being

significantly different than zero). The variables of interest

within the model explained 52% of students selecting a 30:70

instructional delivery based on a Nagelkerke R Square. The

regression reported a Chi-square of 219.65 and a model -2 Log

likelihood of 307.24 (with 10 degrees of freedom). It should also

be noted that the same three cases/outliers were removed from

the analysis to ensure there was no multicollinearity.

The model represented above substantiates the previous

model of why students may consider enrolling in a more blended

learning environment. Of the 10 variables of interest, seven variables were found to be significant in predicting enrollment

in a 30:70 instructional delivery mode (versus other modes). Age

remains a constant within the three tables. It appears that the

younger the student, the more likely they may consider a blended

option. Sex, race and volunteering do not seem to have any impact

on student selection of course instruction. Students who reported

higher levels of hourly employment (per week) were more likely

to consider a 30:70 online instructional deliverable who may

obviously require more flexibility and convenience.

It also appears that the number of classes and which classes

students are enrolled in becomes a more significant variable

as blended instruction applies. Students who were enrolled in

three or fewer courses, considered the criminology course as an

elective course and also having a lower GPA (corresponding to a

C or lower) were more likely to choose the 30:70 option. Might

this be due to students simply prioritizing other classes over this

particular criminology course? Perhaps students registered for

fewer courses equates to a lessening engagement of traditional

materials if given the option. Unfortunately, it appears that these

findings while being interesting does not explain the complexity

surrounding the inter-connectivity of these variables. It also

appears that a longer a student commutes to the university (from

their primary residence) is also having an impact on their selection

of instructional delivery. This variable in combination with taking

fewer courses may be driving a student’s selection or preference

to stay at home more or working more hours (where university

courses are less of a priority).

The findings of these three tables offer some insight in how a

student may be motivated to select a particular course instructional

delivery. Linear and logistic regressions are often performed with

sample sizes over 400 to ensure reduced multicollinearity. While

three cases were removed from two analyses, results should be

taken cautiously. Several variables were also not included from

the sample profile due to a lack of variation in responses. A final

anticipated discussion on a student’s motivations to take an almost

completely online 90:10 course was also not analyzed due to a low

sample size. These findings are conclusive however, it should be

noted that due to a low size of this population, results should be

taken as exploratory [41-50].

Implications

As other researchers have maintained, there is certainly a

complexity surrounding how students select traditional, blended/

hybrid or online classes. While many of these motivations are often

situational and/or circumstantial, this study offers an exploratory

view on why students may self- select into one particular

instructional delivery over another, if given the opportunity, It

appears that age and race are demographic groups which were

considered significant and require more research. We know that

age could be directly correlated with confidence in computer

literacy and/or more traditional face to face methods. However,

more study is needed with perhaps more attention explored within

what we know about distance learning. This study sought to learn

more about commuting and distance education and it appears

that a student’s commute to campus (the longer the commute)

has an impact on their decision to choose a more blended offering

of course instruction. The higher number of hours a student

was employed through any given week in a semester was also a

significant factor in blended learning instruction versus a lack

of it. Flexibility and convenience was found to be a significant

predictor of blended learning while also found to impact a more

traditional face to face delivery (in a negative correlation). This

might suggest that convenience may have more of an impact with

blended learning rather than traditional face to face courses which

is consistent with the literature. A student’s motivation to take

more blended learning could be derived from the necessity of the

class itself. It appears that students who enrolled in the class as

an elective were more likely to consider more blended (70:30 or

30:70) options. This finding may have more to do with a student’s

perception of how important the course is and the priority it is

within a student’s liberal arts education within the institution

studied. These findings offer a glimpse into self-selecting into

an online learning environment. There are few studies that have

offered such an insight into selecting one instructional method

versus another and as such, more study is needed.

To Know more about Social Sciences & Management studies

Click here: https://juniperpublishers.com/asm/index.php

Click here: https://juniperpublishers.com/asm/index.php

To Know more about our Juniper Publishers

Click here: https://juniperpublishers.com/index.php

No comments:

Post a Comment