Reproductive Medicine - Juniper Publishers

Abstract

We describe collaboration between obstetrician

leaders in low resource countries and MFM specialists in promoting a

systematic approach to maternal mortality cases reviews and targeting

feasible quality improvement projects. This effort cumulated in the

presentation and reviews of representative cases of maternal mortality

by emerging obstetrician leaders from Ghana, Uganda, India and Haiti at

the Global Health Scientific Forum of Society of Maternal Fetal Medicine

Annual Meeting in 2012. In addition to large-scale initiatives, groups

of maternal healthcare providers can develop similar global partnership

that can facilitate the goal of reducing global maternal mortality.

Abbreviations:

MDG: Millennium Development Goals; ACOG: American college of

Obstetricians and Gynecology; US: United States; MFM:

Maternal-Fetal-Medicine; SMFM: Society of Maternal Fetal Medicine; RCA:

Root Cause Analysis

Introduction

Maternal mortality is defined as the death of a woman

while pregnant or within 365 days of the end of pregnancy, from any

cause related to or aggravated by the pregnancy or its management, but

not from accidental or incidental causes [1,2]. The Millennium

Development Goals (MDG) 5 signed by 189 heads of state, calls for a 75%

reduction in the global maternal mortality 1990 and 2015 [3]. In 2011,

the world maternal mortality was reported to have decreased from 409,100

in 1990 to 256,300 deaths, a 38% decrease, with only 13 countries noted

to be on track to achieve MDG5 [3]. Overall progress in decreasing

maternal mortality has been inadequate and inconsistent, especially in

low resourced countries. This has resulted in urgent efforts to tackle

maternal morality such as the United Nations Global Strategy for Women’s

and Children’s Health; Saving Mothers, which is a partnership between

American college of Obstetricians and Gynecology (ACOG), United States

(US) and Norwegian governments focusing on the critical 24 hours of

labor & delivery [4]. However, more interventions are needed by more

maternal health organizations, institutions and physicians’

stakeholders to decrease maternal mortality and achieve MDG5.

Purpose

The purpose of this report is to describe a

collaborative process between obstetrician leaders in low resource

countries

and US Maternal-Fetal-Medicine (MFM) specialists in promoting a

systematic approach to maternal mortality cases reviews, identifying

system issues that impact safe care, targeting feasible quality

improvement projects that may lead to a reduction of maternal mortality

in developing countries, and the presentation of representative cases of

maternal mortality for discussion and review at the Global Health

Scientific Forum of Society of Maternal Fetal Medicine Annual Meeting in

2012. Our goal was also to suggest feasible educational

programs based on our experiences that can be adopted by physicians in

resource-high countries who are interested in supporting and

collaborating with counterparts in low-resource countries in the effort

to develop a culture of safety, in-depth blame free maternal mortality

reviews and opportunities to improve the health care delivery system in

order to decrease maternal deaths.

Process

This program occurred as a result of the interest

and efforts of the members of the Society of Maternal Fetal Medicine

(SMFM) sub-committee on Global Health. This committee is committed to

improving the health of women and children in underserved international

communities. The purpose was to identify effective strategies to address

maternal mortality in underserved communities using the following

processes.

1) The first step required that MFM specialists interested in

global health identify and develop a professional, collaborative

and mentoring relationship with an emerging physician leader

from a facility in a low resource country.

2) The next step ensured that the MFM specialists sustain

and maintain an ongoing relationship with the low-resource

emerging leader through bilateral visits, consultations and

electronic teleconferences, emails and other communication

methods.

3) Best practice for root cause analysis (RCA) for maternal

mortality review was promoted. Root cause analysis (RCA)

is a structured method used to analyze serious adverse by

identifying underlying problems that increase the likelihood

of errors while avoiding the trap of focusing on mistakes by

individuals. The goal of RCA is to identify both active errors

(errors occurring at the point of interface between humans

and a complex system) and latent errors (the hidden problems

within health care systems that contribute to adverse events).

RCA generally involves a multidisciplinary team follow a

protocol that begins with data collection and reconstruction

of the event in question through record review and participant

interviews. The ultimate goal of RCA is to prevent future harm

by eliminating the latent errors that underlie adverse events

[5, 6].

4) The low-resource leaders were invited to an inaugural

scientific forum on Global Maternal Mortality at the annual

meeting of the Society for Maternal Fetal Medicine in February

2012. Each member presented a case history that was

representative of one of the key drivers of maternal mortality,

followed by root cause analyses with US MFM experts

facilitating discussions in a global context. The cases were

presented using the 3-delay model (delay in making decisions

to seek medical care, delay in reaching an appropriate facility,

delay in receiving appropriate care on reaching facility) [7],

which recognizes that timely and adequate treatment for

obstetric complications are major factors in reducing maternal

deaths.

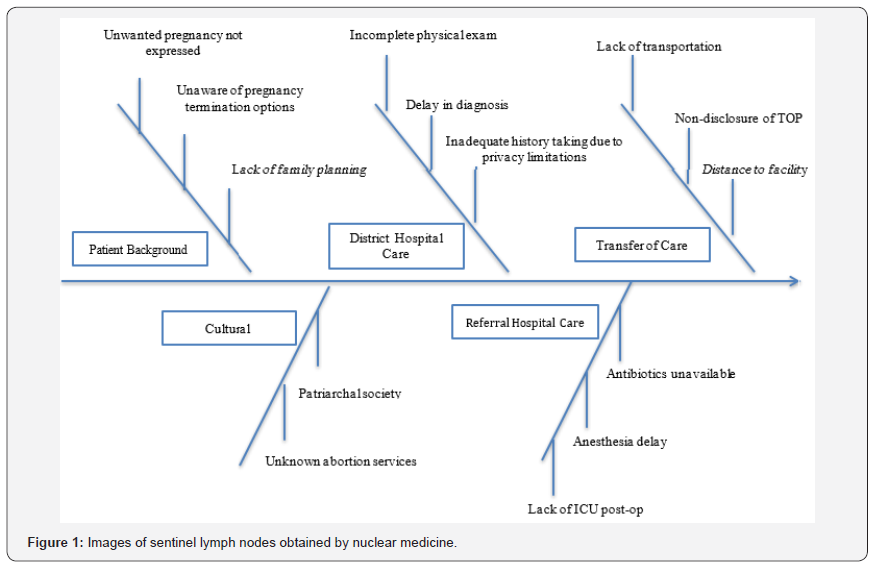

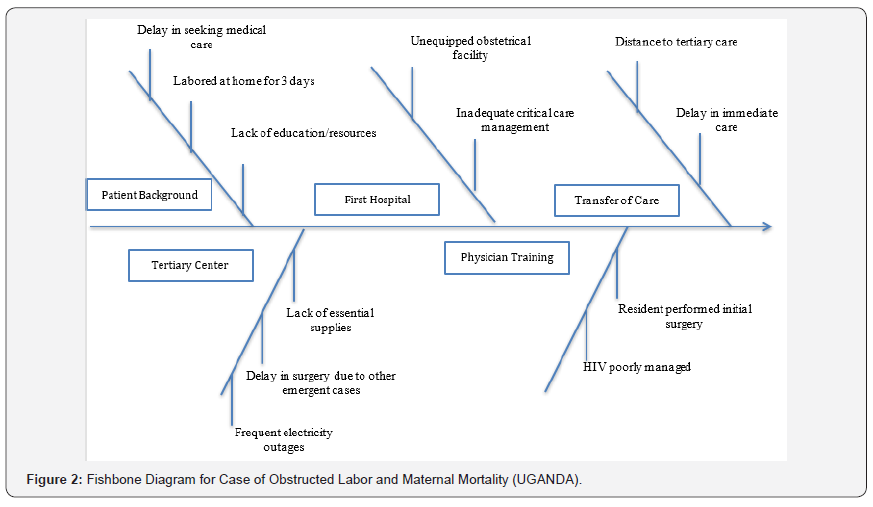

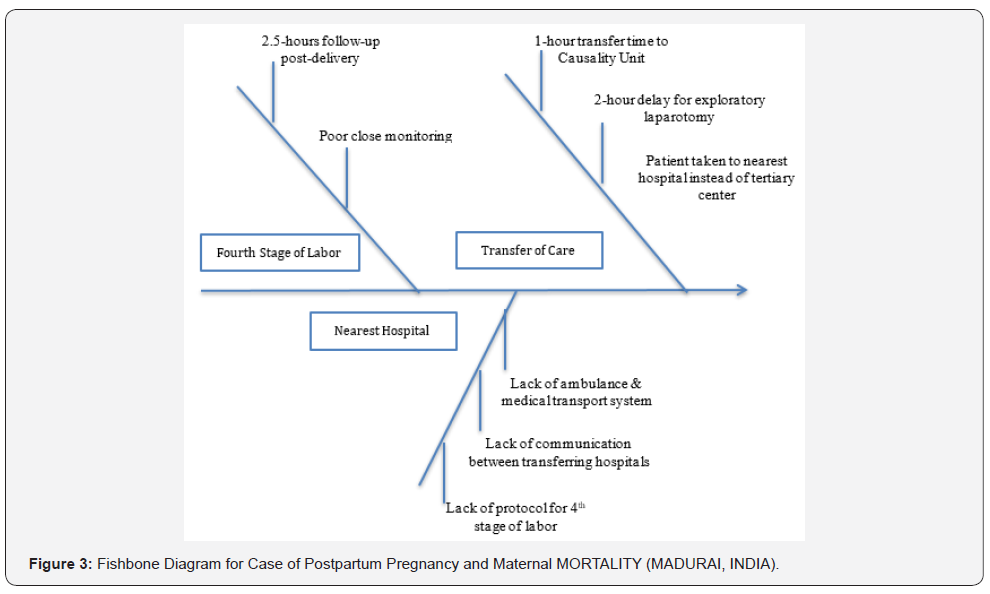

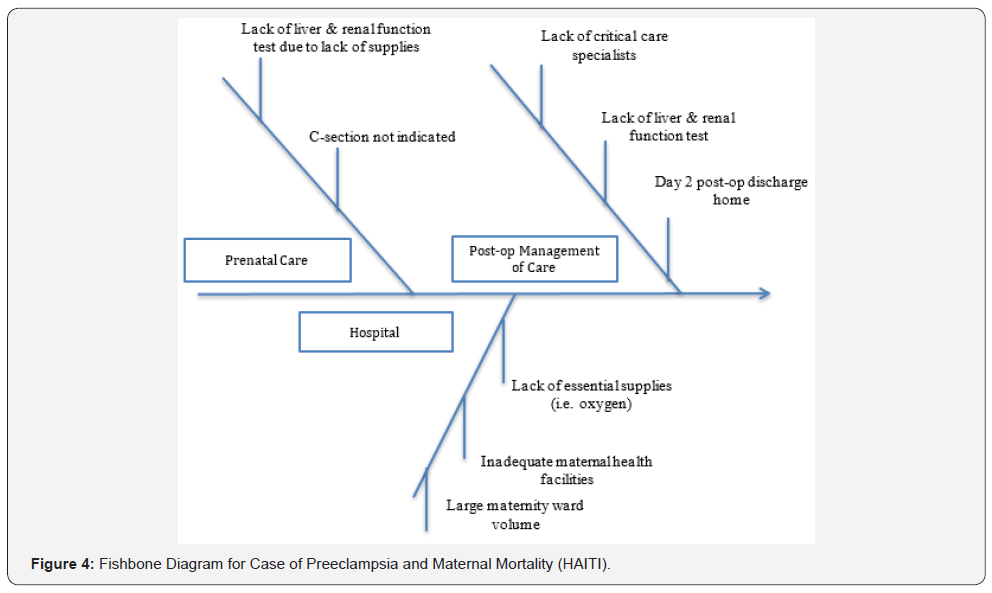

5) A fishbone analysis was also developed for each case

presented. A fishbone diagram, also called a cause and effect

diagram or Ishikawa diagram, is a visualization tool for

categorizing the potential causes of a problem in order to

identify its root causes [8,9].

6) Post-conference, MFM experts-maintained contact and

support with the low resource countries with continued

support for the confidential review system and a focus on

implementing feasible quality improvement projects that

could improve safe care and decrease maternal mortality.

Cases

The four emerging physician leaders were from Uganda, Ghana,

Haiti, and India. These were the countries that the MFM specialists

were able to develop sustainable professional relationships with

local physician leaders. These relationships had been ongoing for

approximately 2 years prior to the SMFM conference. The cases

presented at the Global Health Scientific Forum of the Society

of Maternal Fetal Medicine reflected the leading direct causes

of maternal death – septic abortion, obstetrical hemorrhage,

obstructed labor and preeclampsia.

Septic abortion, accra, ghana

A thirty-seven-year-old Para 5 with three months amenorrhea

procured herbal preparations from a street vendor to terminate

her pregnancy in secrecy. This was unsuccessful, so she obtained

an illicit pregnancy termination at an unidentified private clinic.

On post-operative day 4, she developed severe abdominal pain

and her husband took her to a district hospital. She did not

reveal any information about a pregnancy nor an unsafe abortion

attempt. She was evaluated, but a pelvic examination was not

done. She was admitted for presumed pneumonia with sepsis

and given antibiotics, fluids, and 1 unit of blood. On hospital day

3, she developed fever, productive cough with vaginal bleeding

and passage of tissue. A diagnosis of pelvic abscess was made;

patient had referred her to the tertiary hospital approximately 30

kilometers away by public transport.

Upon arrival, she was febrile, jaundiced, hypotensive and

anuric. She had bronchial breath sounds, tender and distended

abdomen, 12 weeks sized tender uterus, and dilated cervix with

offensive products of conception. The diagnosis was septicemia

secondary to septic incomplete abortion and pneumonia.

Confronted with the physical findings, patient revealed the

history. She did not volunteer information about her termination

previously because of the presence of her husband. She was

resuscitated with normal saline, oxygen and broad-spectrum

antibiotics. Eight hours later, she was taken to the operating room

for uterine evacuation. The cervix was edematous, friable with a

laceration but no evidence of uterine perforation. Very offensive

and copious placental tissue was removed.

Post-evacuation, she was critically ill with unstable blood

pressure, tachycardia and oliguria. Intravenous antibiotics and

blood transfusion were continued. Ten hours post-evacuation

she had a cardiac arrest but recovered after cardiopulmonary

resuscitation. She deteriorated and was declared clinically dead

about ninety-six minutes after the cardiac arrest. Postmortem

diagnosis was bilateral lobar pneumonia with septic abortion.

Septic abortion fishbone and root cause analysis: A fish

bone diagram Figure 1 highlights the problems identified during

the discussion that were considered potential root causes of her

death. These included unwanted pregnancy, inadequate access to

and knowledge about family planning services. By not disclosing

her attempts at pregnancy termination she contributed to a delay

in diagnosis, although an incomplete assessment was performed

at the district hospital. Once transferred to the referral hospital,

resources were limited. Lack of formal education and male dominance are also major factors in this case of mortality from the

complications of an unsafe abortion. At least one in five Ghanaian

women age 15-49 years have no formal education, compared to

one in eight for Ghanaian men.

The cultural issue of male dominance in the Ghanaian society

further widens the gap in equitable access to care [10,11].

Preventive processes that have been identified and implemented

include developing a feedback system, improving access to and

awareness of family planning services, and improve awareness of

Ghana’s abortion laws to health providers. Long-term projects that

involve government policy and major funding include increasing

the education of girls, and the empowerment of women politically

and economically. Also required are health care resources such as

ICU, availability of antibiotics and skilled health care providers.

Obstructed labor, Mbarara, Uganda

A 28-year-old primigravid HIV positive Rwandese refuge

was admitted following referral by a primary health facility for

obstructed labor with fetal death at 39 weeks of gestation. She was

not on antiretroviral medications and had an unknown CD4 count

and viral load. She had labored for three days at home. She started

pushing at home under the care of a traditional birth attendant

who sent her to the primary health facility because the baby had

“failed to come.” Subsequently, the primary health facility referred

her to the regional hospital, which was 40 kilometers away, at

which exploratory laparotomy revealed a lower segment uterine

rupture, massive hemo-pyo-peritonium with the placenta in the

abdominal cavity and extensive necrosis of the lower uterine

segment and pelvic fascia. A macerated male stillbirth of 3.9

kilograms was delivered and total hysterectomy with bilateral

internal iliac artery ligation done within 85 minutes of arrival. Four

units of whole blood were transfused during the operation. The

patient remained hypovolemic with tachycardia and poor tissue

perfusion post operatively. She developed signs of pulmonary

edema, had convulsions; deteriorated and expired on the fourth

day of management. Cause of death was cardiopulmonary failure

and septicemia resulting from ruptured uterus following neglected

obstructed labor in the community. No autopsy was done.

Obstructed labor Fishbone and Root Cause Analysis: Figure

2 shows the fish bone diagram that highlights the root causes of this

mortality. There was delay in making the decision to seek medical

care, since the patient labored at home for more than 3 days. There

was a crucial delay in reaching the appropriate facility because

the initial health center was not equipped for critical obstetrical

procedures and she had to be transported 40 kilometers to the

tertiary center. There was also a delay in receiving appropriate

management on arrival at tertiary center. A program implemented

in this institution is a maternal death confidential inquiry audit

which involves tracing all the way back to the deceased’s home

and holding discussions with all concerned.

Discussions are arranged with the health workers directly

involved in the management of the deceased mother, immediate

family members, and community leaders. The final audit and review

is utilized to recommend, advocate and implement programs

to reduce maternal mortality. This institution in collaboration

with counterparts from high resource institutions has initiated

achievable quality improvement projects as requirements for the

OBYN residents as a method to target systems deficits in care.

Peripartum hemorrhage, madurai, india

A multiparous 33-year-old, at 40 weeks of gestation with

uneventful antenatal course was admitted at a primary facility

in spontaneous labor and progressed well. She had a second

stage of approximately ninety minutes complicated by maternal

exhaustion and fetal bradycardia. Outlet forceps were applied

and a healthy female baby weighing 3.4kg was delivered. The

episiotomy wound was sutured, and the cervix and vagina explored

and found to be intact. There was no postpartum hemorrhage,

and she was transferred to the post-partum unit. Approximately

two-and-a-half hours later, patient was found unconscious by her

attendant and could not be aroused. Patient was resuscitated and

subsequently was referred to a tertiary care center for further

management. She was received 1-hour later in the Casualty unit of a regional

hospital because transporting taxi-driver felt that the patient was

deteriorating and would not make it to the designated tertiary

center. Her pulse was feeble, blood pressure un-recordable,

and patient was gasping. She was resuscitated with parenteral

fluids and intubated. On abdominal examination, uterus was 24

weeks size and pushed towards the right side by a boggy mass

extending from the bladder on the left side, halfway to the level of

the umbilicus. Vaginal exam revealed normal cervix and minimal

vaginal bleeding with fullness felt in the left fornix.

Ultrasound showed a suspected left side pelvic hematoma

close to the uterus with a possible ruptured uterus. Laboratory

results revealed bleeding coagulopathy with anemia, and

she was appropriately transfused with fresh frozen plasma

and packed red blood cells. Patient was taken for exploratory

laparotomy approximately one hour after arrival. Intraoperative

findings revealed a left broad ligament and a rupture of the left

lateral uterine wall. Total abdominal hysterectomy left salpingooophorectomy

and bilateral internal iliac artery ligation was

performed. Postoperatively, patient was transferred to ICU.

Packed cells, fresh frozen plasma and platelet transfusions were

continued. While the altered coagulation profile was corrected, the

hypotension persisted. Neurological evaluation revealed global

cerebral damage. Patient developed repeated episodes of cardiac

arrest and finally could not be revived. She expired approximately

24 hours after delivery.

Peripartum hemorrhage fishbone and root cause analysis:

A fish bone diagram Figure 3 highlights the problems identified

during the discussion that are considered potential root causes

of the maternal mortality. In this postpartum hemorrhage case,

there was no obvious external blood loss to alert the healthcare

providers instead a significant volume of blood loss occurred

intra-abdominally, leading to hemorrhagic shock and subsequent disseminated intravascular coagulation. There was inadequate

monitoring of the fourth stage of labor. It is likely that if the

pelvic hematoma was recognized earlier and appropriate surgical

treatment was done immediately, the patient’s life may have been

saved. During transport to a higher referral center, there was

a delay in reaching an appropriate facility, since a taxicab was

transporting the patient to a tertiary center, when she became

“moribund” and she was taken to a nearest hospital.

Preeclampsia, haiti

A 37-year-old, primigravida at 39 weeks of gestation was

referred because of new onset hypertension treated with

methyldopa. Blood pressure was 170/120. Ultrasound showed

a fetus, in cephalic presentation with estimated fetal weight less

than the 10th percentile, normal amniotic fluid, umbilical artery

Doppler with no end diastolic flow and the placenta had multiple

lacuna. Platelets, renal function tests and liver function tests were

not done because of a lack of reagents. A diagnosis of preeclampsia,

intrauterine growth restriction and suspected placenta abruption

was made. Blood pressure was controlled and stabilized with

intravenous Apresoline. An uncomplicated cesarean section was

performed because of the suspected abruption. She delivered

a healthy female baby, birth weight 2580 grams with a normal

placenta noted. Postpartum; her blood pressures stabilized to

140-130/80. She was asymptomatic with no complaints; renal

and liver function tests were not done. On postpartum day 2, her

blood pressure was 140/80, with normal clinical evaluation. She

was discharged home on Methyldopa.

She presented to the Emergency Room the next day

(postpartum day 3) with respiratory distress, epigastric pain,

cough productive of whitish sputum, blood pressure of 220/120

and crackles on both lungs. The differential diagnoses entertained

were pulmonary edema, pulmonary embolism and hepatic

rupture. She was treated with Magnesium sulfate and Apresoline

but died during resuscitation. An autopsy was not performed.

Preeclampsia fishbone and root cause analysis: A fish

bone diagram Figure 4 highlights the problems identified during

the discussion that are considered potential root causes of this

mortality. This case highlights the contribution of inadequate

management on arrival at a health facility to maternal mortality.

The only indication for cesarean delivery was the ultrasonic

abruption diagnosis. In this institution, patients with cesarean

section are discharged on the 3rd post-operative day but because

of high patient load and inadequate maternal care facilities,

this patient was discharge home on the 2nd post-operative day.

Liver and renal function tests that might have demonstrated

severe preeclampsia were not performed prior to discharge. RCA

highlighted lack of resources such as critical care specialists;

oxygen in the emergency room and laboratory test reagents.

Discussion

We have used four illustrative examples of maternal mortality

to make specific points about obstetrical care in different

international settings noting that these cases do not portend to

describe all the common problems at each site or country. The

death from unsafe abortion emphasizes the fact that despite

Ghana’s liberal abortion law, illicit abortion continues because

of lack of public education, and inadequate resources [11].

The death from obstructed labor from Uganda highlights the

pivotal role of traditional birth attendants and inadequate

transportation infrastructure [12]. The case of unapparent postpartum

hemorrhage from India; granted that this case may be

challenging in any high resource country nevertheless emphasizes

the importance of the fourth stage of labor and the need for close

monitoring of the immediate postpartum period. The maternal

mortality from severe preeclampsia from Haiti emphasizes

inadequate maternity health care facilities and lack of ancillary

resources.

Many of the drivers of maternal mortality such as

transportation, facilities, drugs, equipment, skilled health care

workers and cultural taboos are daunting and overwhelming in

scope and enormity. Successful interventions would require major

political will, policy changes, health-care infrastructure, largescale

funding and fundamental cultural changes [13]. Therefore

even though reviewing these maternal mortality cases may seem

to be “hand-wringing”, however our goal was to report feasible

projects that can be undertaken by individual or small groups

of obstetricians, MFM specialists or professional organization

committees in collaboration with physicians in low-resource

communities with the aim to reduce global maternal mortality.

The cases presented were based on professional mentoring

relationships developed over time with specific physician leaders

in the four countries. The MFM specialists were able to provide

training, promote the use of RCA, help categorize risk factors

associated with maternal mortality, and act as a resource. Most

importantly, the low resource physician leaders with support

from the MFM specialists were able to implement feasible and

achievable improvement projects derived from the systematic

maternal mortality review aimed at reducing maternal mortality

in their local environment. For example, the site in Ghana worked

on system to provide feedback to referring health centers, the care

team and the administrative staff. The Uganda site developed an

emergency cupboard for cesarean delivery supplies as a result

of the mortality, the site in India reviewed the process of close

monitoring of the 4th stage of labor and the Haiti site ensured that

wall oxygen was available in the maternity unit. Our experience can

be used to make some suggestions for international collaboration

to reduce maternal mortality as follows:

1) The first step requires that the physicians in high

resource communities interested in global health and maternal

mortality expand their knowledge on all aspects of maternal

mortality including global scope, systematic maternal

mortality reviews, root cause analysis process including fish

bone diagram analysis, standard protocols to obstetrical

emergencies, quality improvement projects implementation

and current initiatives. Maternal mortality is a complex

problem involving complex system problems; the motivated

physician may need to learn the LEAN or Kaizen principles.

The term ‘lean thinking or Kaizen principles’ is based on the

production philosophy, which evolved at Toyota to understand

processes in order to identify and analyze problems. Lean

thinking has been applied successfully in a wide variety of

healthcare settings. The four general components of lean

thinking in use are:

a. methods to understand processes in order to

identify and analyze problems

b. methods to organize more effective and/or

efficient processes

c. methods to improve error detection, relay information

to problem solvers, and prevent errors from causing harm

d. methods to manage change and solve problems

with a scientific approach [13].

2) The trained physicians can then identify a physician

leader in a low resource country to develop a professional

and cooperative relationship. Identifying a compatible global

physician partner can be challenging, and one may have to

access experienced global health researchers, institutional

and national programs.

3) Exchange visits are crucial to implementing a global

health initiative. Ideally this should be bilateral. The high

resource physician visits the low resource institution to get

a scope of the local culture and challenges and thus be in a

position to help train, guide and support maternal mortality

reviews and initiatives. It is also important that the global

health counterpart visit the high resource institution to learn,

experience and be motivated.

4) Professional organizations in high resource countries

should be encouraged to hold more global sessions to which

emerging leaders are invited and sponsored. This will greatly

increase motivation, mentoring and training of low resource

physicians; increase collaborations and the sustainability of

programs.

5) Constant and sustainable communication is the key to

successful global collaboration especially between visits. In

our programs we have used some form of telecommunication

to have a regular conference at regular intervals. Ideally audiovisual

telecommunications such as SKYPE, WEBEX are best,

but because of limited Internet capacities in some countries

we have had to depend on an audio only platform, which are

more stable. The high-resource may need to be on a “on-call”

schedule for access by phone or email in the advent of unusual

or catastrophic obstetrical emergencies in the low resource

country.

6) Finally, we believe that the collaboration should result in

the identification and implementation of “specific, quantifiable

and finite” quality improvement projects that can promote safe

care and reduce maternal morbidity and mortality in the local

region. Evidence shows the more specific the intervention as

compared to broad interventions, the stronger the evidence

that the intervention can help reduce maternal mortality [14].

In conclusion, we have shown that a group of MFM experts

interested in global health, can develop mentoring and professional

relationships with global counterparts that can facilitate systemic

reviews of maternal mortality, lead to an awareness of risk factors

and the implementation of preventive programs that can reduce

maternal morbidity and mortality. We believe that it is possible to

develop a group of specialists with a maternal health focus who

can support local capacity building to facilitate local maternal

mortality reviews and the implementation of appropriate

prevention program.

I like the content which was mentioned above. If any of the final year students are looking for the image processing final year projects

ReplyDelete