Archaeology & Anthropology - Juniper Publishers

Summary

From a graphic point of view, smiles are prior to

tears. While the smiles are documented in human graffiti from the

Paleolithic period (Middle Magdalenian), tears are documented much

later, in animals of post paleolithic periods. These data help us to

make a few reflections about our way of seeing art, which may be

influenced by our culture, too serious, for a few graphs that are not so

much.

Keywords: Smile; Laughter; Paleolithic art; Evolution

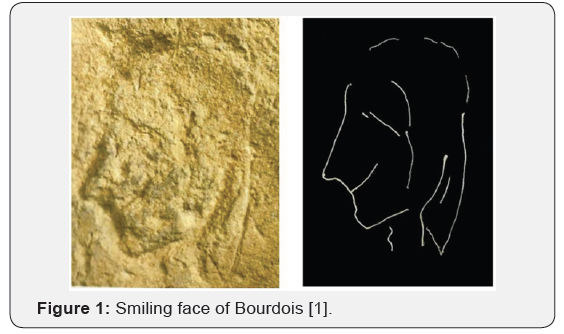

The smile of Bourdois

The figure reproduced below is a cave engraving of

the Bourdois shelter, located in the Vienne, France. They will agree

with me that at first glance it does not seem to have anything of

particular. It is a small human face endowed, of course, with a broad

smile [1]. But, if we consider that the spelling in question is 15,000

years old, the thing changes, and the impression that the smile produces

increases. Indeed, we are facing one of the first smiles in the History

of Art. The smile of Bourdois is not, far from it, as famous as that of

the Mona Lisa, and yet its transcendence is much greater. Even if only

because a smile from 15,000 years ago contains many more puzzles than

one of just four centuries. And if not, look closely at the face, is it

possible to look at this smiling face for a long time without smiling?

This reaction, almost instinctive, says a lot about the human species,

about who we are and why we are here (Figure 1).

This enigmatic fascination, which all attentive

observers share, is caused by the intimacy of a gesture of different and

partly undefined nuances. And is that every smile always harbors a

suspicion: the shadow of dissimulation. You can see in it the trace of

deceit, submission or fear. But, although the shadow

of a doubt looms over its inner light, the smile is, above all, an

expression of pleasure and happiness. For a smile manages to stay true

to itself and its own mystery. That is to say, what really hides is,

neither more nor less, than the secret of happiness.

On the other hand, the fascinating attraction that a

smile exerts can be understood as a power of seduction that, Freud did

not hesitate to describe as erotic [2]. And although the genius of

psychoanalysis was too often carried away by interpretations of a sexual

nature, it is quite possible that this time it was not misguided.

Almost all the specialists in gestural mimicry agree in affirming that

the smile has an erotic function. Even scholars of human behavior have

highlighted the erotic relationship of

the smile in current primitive peoples [3]. This relationship may be

very old, perhaps prehistoric. In paleolithic art we have four examples

in which the smile is associated with anthropomorphic figures with

upright sex [4]. These spellings seem to reflect a relationship between

happiness and sexual satisfaction.

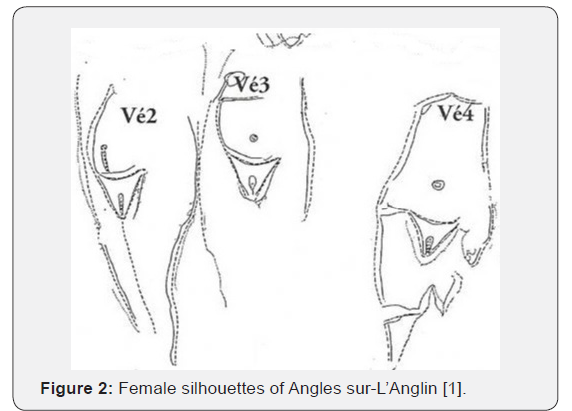

The female silhouettes of Angles-sur-l’Anglin

A few meters from the smiling face of Bourdois we

have, in the same frieze, four sculpted female silhouettes, in a

position that today we would not hesitate to describe as erotic. So much

so, that Guthrie has compared these paleolithic profiles with the

images of the Playboy. The comparison with current pornography deserves

to be criticized at least in two essential points. The first is that

porn is characterized by its seriousness, it is, in the words of

Braudillard, deadly serious [5]. Which means that there has been a

process of verification of the erotic in the pornographic, or, to put it

another way, the vital and joyful component of the erotic has been

eliminated, turning it into something mechanical and artificial, reduced

to an act highly stereotyped And secondly, the pornographic in Western

culture excludes the sacred, something that does not happen for example

in the East.

However, as can be seen in three of the graphs reproduced

below, the silhouettes of Angles-sur-l’Anglin, have an inescapable

erotic tone. The pose of naked bodies has a disconcerting effect.

It is almost impossible not to see in them the bodies of contemporary

models or sex symbols. What does not lead us to ask

the following question, what we see is conditioned by our pornographic

aesthetics or does it have some biological basis? Look

at the sinuous lines that frame the vulvas and delineate the hips

and part of the legs. These parts of the female body are erotic in

virtually all human cultures [6].

The reason why aesthetics uses these forms has a biological basis, that is, a “practical” sense. It is no coincidence that the beauty ideals of a tribe of Trobians and Westerners are so similar [7]. Nor that, apparently, these ideals, based on body proportions, have not changed over time. Well, they respond to a purpose, which is to stimulate reproduction, because according to certain studies, female hips and legs without visual indicators of women’s fertility. Furthermore, not only the silhouettes of Angles-sur-l’Anglin have that disconcertingly modern character; but there are other similar examples in the caves of Le Gabillou and La Magdeleine. The position of these female bodies, reminiscent of Goya’s Nude Maja, is eminently erotic. For example, the position of the arm behind the head in the bas-reliefs of La Magdeleine, is an expression of enjoyment that is also observed in sexual scenes from Roman times. In a painting of the House of the Restaurant of Pompeii (1st century), A woman bends her arm in this way while practicing sex with a man. The scene, of obvious interpretation in the Roman case, is not in the prehistoric. What is evoked in Paleolithic art is not the act itself, but something more complex whose final meaning escapes us. But what is interesting here is to point out that artists or paleolithic artists are the creators of a visual eroticism that is surely different from what we understand today. It was probably a happy and perhaps sacred eroticism, but the result of the complex world of seduction, the mystery of attraction, of creation and of life (Figure 2).

The reason why aesthetics uses these forms has a biological basis, that is, a “practical” sense. It is no coincidence that the beauty ideals of a tribe of Trobians and Westerners are so similar [7]. Nor that, apparently, these ideals, based on body proportions, have not changed over time. Well, they respond to a purpose, which is to stimulate reproduction, because according to certain studies, female hips and legs without visual indicators of women’s fertility. Furthermore, not only the silhouettes of Angles-sur-l’Anglin have that disconcertingly modern character; but there are other similar examples in the caves of Le Gabillou and La Magdeleine. The position of these female bodies, reminiscent of Goya’s Nude Maja, is eminently erotic. For example, the position of the arm behind the head in the bas-reliefs of La Magdeleine, is an expression of enjoyment that is also observed in sexual scenes from Roman times. In a painting of the House of the Restaurant of Pompeii (1st century), A woman bends her arm in this way while practicing sex with a man. The scene, of obvious interpretation in the Roman case, is not in the prehistoric. What is evoked in Paleolithic art is not the act itself, but something more complex whose final meaning escapes us. But what is interesting here is to point out that artists or paleolithic artists are the creators of a visual eroticism that is surely different from what we understand today. It was probably a happy and perhaps sacred eroticism, but the result of the complex world of seduction, the mystery of attraction, of creation and of life (Figure 2).

Prehistoric eroticism, and its Paleolithic graphic expression, have their roots in human evolution. Specifically, in the development of our particular mode of sexual reproduction. About two million years ago, our hominid relatives began a strategy of reproduction that we could describe as optimistic, since it consisted, mainly, of having sex a more or less constant pleasure. This fact was crucial in the evolution of our species. Our reproductive success (it is estimated that we are around 7,000 million people in the world) is unparalleled in the history of placental mammals. If we are a prolific species par excellence it is thanks to the intrinsic quality of our sex to provide us with pleasure at any time of the year. The other animal species either do not experience as much pleasure or are subject to short periods of heat. Human sexuality does not depend, like that of other mammals, on the olfactory stimuli and the hormonal chemistry of pheromones; but predominantly visual stimuli, based mainly on physical features and body proportions [7]. This explains, to a certain extent, the eroticism of artistic expressions. Today the pornographic market has reduced the erotic to its minimal expression. The most visited websites on the internet are, by far, pornographic. We are a species that we bet on the pleasure of reproduction. And natural selection has favored this optimistic strategy.

The Tears

From a graphic point of view, smiles are prior to tears. The

tears that appear on the faces of the Tassili cows, studied by Le

Quellec [8], seem to have a symbolic meaning. We have to go

back to the Egyptian period (2000 BC) to identify the tears, not

in a human, but in a cow again, which apparently cries because

they are going to sacrifice their bull in a relief of a sarcophagus

of Deir el- Bahari Are human feelings attributed or is it that these

feelings are not exclusively human? Are historical cultures more

pessimistic than prehistoric ones? About four million years ago,

the Mesopotamian civilization left us a magnificent example of

the existential pessimism that has developed in our culture in a

way surreptitious as a principle of unquestionable reality. Since

then, pessimism has slowly imposed itself, making us believe

that the human species is sinful by nature. That’s what researchers

think of the human imagination as Beltrán [9]. And it is that

the real, in our world, is the serious thing, that is, the drama of

life. In other words, more Freudian, our principle of reality is occupied

by the drama of the serious. This is an automatism that

operates mechanically in our culture without hardly questioning.

However, is optimism defining us as a species? The instinct

of reproduction is the means by which the organic announces

the joy of existence. Therefore, what we call optimism is the

force that animates existence and drives reproduction. We can

appreciate the laughter in the animals, the song of the birds, the

tail of the dog, the purring of the cats. Is the joy of existence the

engine of evolution? From this point of view, the upright position

of the sapiens animals, allows the face to be seen, which is fundamental

in the non-verbal communication of the smile. And besides,

the bipedal position exposes the sexual organs, “shames”

that all human cultures cover in some way. Shame is one of the

fundamental axes of laughter. This feeling has played an important

role in the development of human humor, in, for example, the

phallic exhibitions.

To Know more about Archaeology & Anthropology

Click here: https://juniperpublishers.com/gjaa/index.php

To Know more about our Juniper Publishers

Click here: https://juniperpublishers.com/index.php

Click here: https://juniperpublishers.com/gjaa/index.php

To Know more about our Juniper Publishers

Click here: https://juniperpublishers.com/index.php

No comments:

Post a Comment