Anatomy Physiology & Biochemistry International Journal

The association between periodontal disease and cardiovascular disease is based on the systemic inflammation which also involves the periodontopathogenic bacteria. Our research study investigated the prevalence of periodontal disease in a group of 20 patients with cardiovascular disease, divided into 2 groups according to the presence of periodontal disease, demographic and environmental factors. Periodontal and cardiovascular disease were established according to the current international classifications. The systemic inflammation was assessed by the following markers: leukocytes number, C-Reactive Protein, ESR and fibrinogen. The periodontal disease was assessed based on the bacterial plaque index, gingival bleeding index and clinical attachment loss.

Our results indicated that the prevalence of periodontal disease in patients with cardiovascular disease was 55%, and higher in females than males. Among patients with cardiovascular disease, those in the rural area had a poor oral hygiene. Patients with hypertension showed a higher number of teeth with periodontal pockets compared with patients with other cardiovascular diseases. There were no significant changes in systemic inflammatory markers related to the presence of periodontal disease.

Keywords: Periodontitis; Cardiovascular disease; Prevalence; Periodontal pockets; Systemic inflammatory markers

Abbrevations: AC: Anticoagulants; AHA: American Heart Organization; CAL: Clinical Attachment Loss; CHF: Chronic Heart Failure; CI: Calculus Index; CIHD: Chronic Ischemic Heart Disease; CRP - C Reactive Protein; CVD: Cardiovascular Disease; CVE: Cerebrovascular Event; DI: Debris Index; DSR: Digital Subtraction Radiography; ESR: Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate; GBI: Gingival Bleeding Index; GDPR: General Data Protection Regulation; HBP: High Blood Pressure; IL-1β: Interleukin -1 Beta; IHD: Ischemic Heart Disease; MI: Myocardial Infarction; OHI-S: Oral Hygiene Index-Simplified; PA: Platelet Antiaggregants; PD: Periodontal Disease; TNF-α: Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha; US: United States; WBC: Leukocyte; WHO: World Health Organization

Introduction

Periodontal disease (PD) is a chronic inflammation that occurs in response to the periodontopathogenic bacteria and causes the progressive and irreversible destruction of the periodontal tissues and eventually, leads to tooth loss [1]. Numerous studies have demonstrated the association between PD and CVDs [2] such as arteriosclerosis [3], dyslipidemia [4] and hypertension [5]. According to prospective observational studies, this association is based on the systemic inflammation initiated by the microorganisms in the biofilm on the dental surfaces. However, a clear link has not been yet established [6]. PD and heart disease could have simultaneous onset, but singularly, one disease cannot induce the another [7]. This blurring persisted for several decades until several important studies established the influence of periodontal disease treatment on cardiovascular disease outcomes [8]. Since periodontal disease does not induce pain in the early stages and has a slow evolution, it is often left untreated [9,10].

According to the WHO, cardiovascular diseases are the number one cause of death globally [11]. In 2012, there were 17.5 million deaths globally, accounting for 31% of the total deaths [12]. Among cardiovascular diseases, IHD and cerebrovascular disease are the most common causes of death worldwide. According to the AHA, 795,000 people suffer a stroke annually [13].

The oral cavity is a reflection of a patient’s overall health, harmful habits and nutritional status. It is the entry as well as the site of microbial infections that also alter the general health [14]. Several theories explain the link between periodontal disease and heart disease. One theory is that oral bacteria entering the blood stream could affect the heart by attaching to the atherosclerotic plaques in the coronary arteries and leading to clot formation. Coronary artery disease is characterized by thickening and hardening of the coronary arteries walls due to the formation of plaques. Blood clots may obstruct the normal blood flow, restricting the amount of nutrients and oxygen required for the heart to function properly. This may lead to heart attacks. Another possibility is that the systemic inflammation caused by periodontal disease increases plaque formation, which may contribute to inflammation of the arteries walls. Researchers have found that people with periodontal disease are almost twice as likely to suffer from coronary artery disease as those without periodontal disease [15].

The inflammatory potential of periodontal disease is manifested at macromolecular level through systemic dissemination of local mediators such as CRP, IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF-α. According to Chambers et al., this goal together with the increased number of inflammatory molecules could be involve in cardiovascular disease [16]. There is strong relationship between the periodontal and cardiovascular diseases and two directions have been the focus of delineating this relationship: bacteria from the oral cavity directly exacerbate cardiovascular disease or alter the systemic risk factors of cardiovascular disease; the chronic periodontal inflammation at the focus of infection increase circulating levels of inflammatory mediators, and/or bacteria disseminated into the circulation elicit elevations in systemic host inflammatory mediators that exacerbate cardiovascular disease directly or alter other systemic risk factors for cardiovascular disease [17].

The purpose of this study was to assess the prevalence of periodontal disease in a group of patients with cardiovascular disease and to establish the correlation between serum levels of inflammatory markers and periodontal status in these patients. The specific objectives of the present study were:

a. Evaluation of the prevalence of periodontal disease in a group of patients with cardiovascular disease.

b. Assessment of clinical parameters and severity of periodontal disease (bacterial plaque index, gingival bleeding index, clinical attachment loss) and the form of cardiovascular disease according to current international classifications.

c. Evaluation of systemic inflammatory markers (leukocytes, CRP, ESR, fibrinogen).

Materials and Methods

The study was conducted on 20 patients diagnosed with cardiovascular disease, 12 women and 8 men aged between 42 and 82 years, hospitalized in the Cardiology 1st Clinic, County Emergency Clinical Hospital Cluj-Napoca. All the patients signed the informed consent and the protection of personal data GDPR for participating to this study.

The patients were enrolled based on exclusion and inclusion criteria. The inclusion in the study was based on two criteria:

a. Minimum 6 teeth present in the oral cavity.

b. The diagnosis of cardiovascular disease.

The exclusion criteria were:

a. Complete edentation or presence of less than 5 teeth.

About half of all-American adults-117 million individuals— have one or more preventable chronic diseases, many of which are related to poor quality eating patterns and physical inactivity with more than two-thirds of adults and nearly one-third of children and youth being overweight or obese [8]. With the dietary link of diet and disease in mind, one must consider the application of diet upon biochemical processing overall and in particular for this work, with that of ADZ progression. Dietary demographics may play a pivotal role in the radically reduced rates of progression between the United States and that of other countries such as Singapore. It may be a point to consider that, although certain fish and shellfish contain greater levels of mercury content, they also contain essential fatty acids and are a rich protein resource that is needed to promote neuro-physiological processing through normal biochemical pathway processing [20,21].Research is now more than ever asking the question whether diet could play a substantial role in ADZ progression as well as many other dementias when considering the population demographics between East and West.

b. Severe general conditions that didn’t allow patient’s examination.

c. Other general diseases that could increase the levels of systemic inflammatory markers.

Using the Excel program, all data obtained in this study were organized in frequency tables, sectorial graphs (pie charts) and contingency tables. Information on the type of edentation according to the Kennedy classification, the appearance of the dental units, the presence of the dental fillings, their aspect and the material used, the aspect of the periodontium, the presence of gingival inflammation, bacterial plaque and tartar were recorded and compared. The major drawback in this study was the lack of periodontometry because this examination was performed in the hospital environment, not in the dental office. The periodontal clinical examination assessed the gingival bleeding, periodontal pockets depth, gingival retractions and tooth mobility.

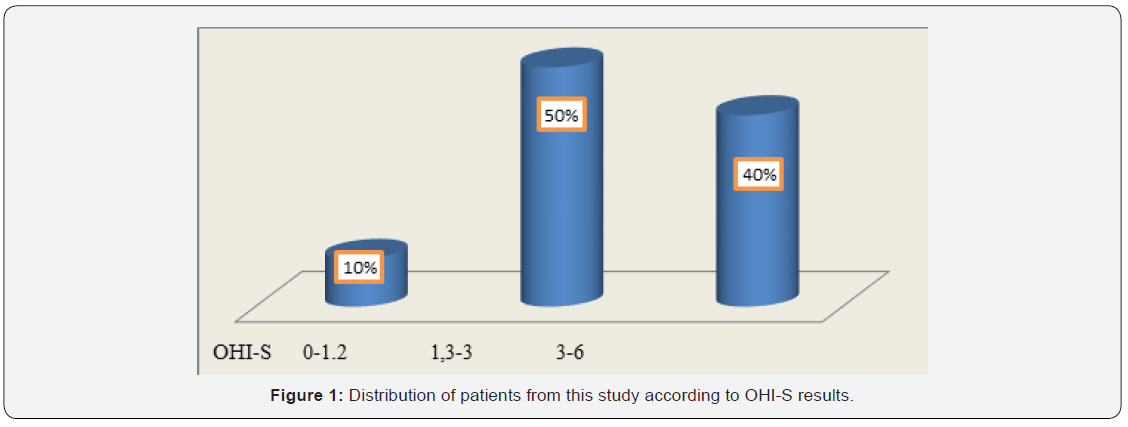

To evaluate oral hygiene, we calculated the OHI-S index (Greene and Vermillion, 1964) in patients with cardiovascular disease. Plaque examination was performed by inspection without staining solutions. The following dental surfaces were examined: the vestibular surface of teeth 1.6, 1.1, 2.6 and 3.1, and the lingual surfaces of teeth 3.6 and 4.6. The values of the debris index (DI) were registered as follows: 0 = absence of the bacterial plaque; 1 = supragingival plaque in the cervical 1/3 of the tooth, on the parcel; 2 = plaque in the middle 1/3 of the tooth; 3 = plaque in the occlusal or incisal 1/3 of the tooth. The values of the CI index were as follows: 0 = absence of the tartar; 1 = supragingival tartar in the cervical 1/3 of the crown; 2 = supragingival tartar in middle 1/3 of the crown and islands of subgingival tartar; 3 = tartar and in occlusal or incisal 1/3 of the tooth and a band of subgingival tartar. The values obtained in the assessment of the above areas were collected and divided by the total number of assessed areas for both DI and CI. Values obtained for DI and CI were collected and the OHI-S value was obtained. Interpretation of OHI-S index values was the following: between 0 and 1.2 = good oral hygiene; between 1.3 and 3 = satisfactory oral hygiene; between 3.1 and 6 = poor oral hygiene.

According to Maurizio S. Tonetti & al, understanding the periodontitis stages, as well as the correct treatment applied in each of these stages is crucial for an immediate treatment at these patients [18]. In order to assess the periodontal health status, we evaluated the GBI [19]. This is a reliable, easy-to-use indicator that reveals the presence or absence of gingival inflammation [20]. After about 10-15 seconds, the occurrence or absence of bleeding was recorded. The number of registered positive units was divided by the number of gingival margins examined and the result was multiplied by 100 for the expression of the percentage indicator. It was shown that scores obtained with this index were statistically correlated with those obtained from the application of the gingival index GI [21,22]. Several studies showed that the absence of gingival bleeding was a good indicator of the healthy marginal periodontium. Other studies demonstrated that the surfaces that bled upon probing did not show extensive tissue destruction in all cases. Moreover, this parameter is not correlated with the degree of gingival inflammation in smokers. The diagnosis of periodontal disease has been established based on the clinical criteria: multiple gingival attachment loss, grade 2 or 3 dental mobility with tooth malposition, bone resorption that could be clinically observed, gingival and periodontal pathological changes (presence of periodontal pockets, gingival bleeding, ulcers). Since the patients were hospitalized, the radiological examination could not be performed, in order to validate and complete the clinical diagnosis. The biochemical parameters assessed as markers of systemic inflammation included: WBC, CRP, Plasma fibrinogen and ESR.

Results

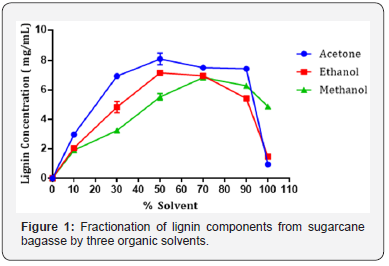

In this study, 20 patients were enrolled: 63% were women aged between 65 and 77 years and 37% men aged between 43 and 82 years. Among patients from the rural area, 73% were women and 27% were men. Among patients from the urban area, 55% were men. In this study group, 11 patients with CVD had PD (55% of which 35% were females and 20% were males). As represented in Figure 1, OHI-S indicated that 40% of all the patients achieved values ranging from 3 to 6, suggesting poor oral hygiene. Of these, 75% were females coming from rural areas. Among patients with both CVD and PD, 64% had a poor oral hygiene at the time of OHI-S assessment. These results suggested that in patients with CVD, the poor oral hygiene was correlated with the oral status and could be a risk factor for the occurrence and/or worsening of PD. The neglected oral hygiene observed in these patients might be the result of the associated general diseases.

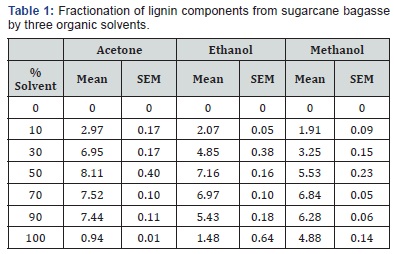

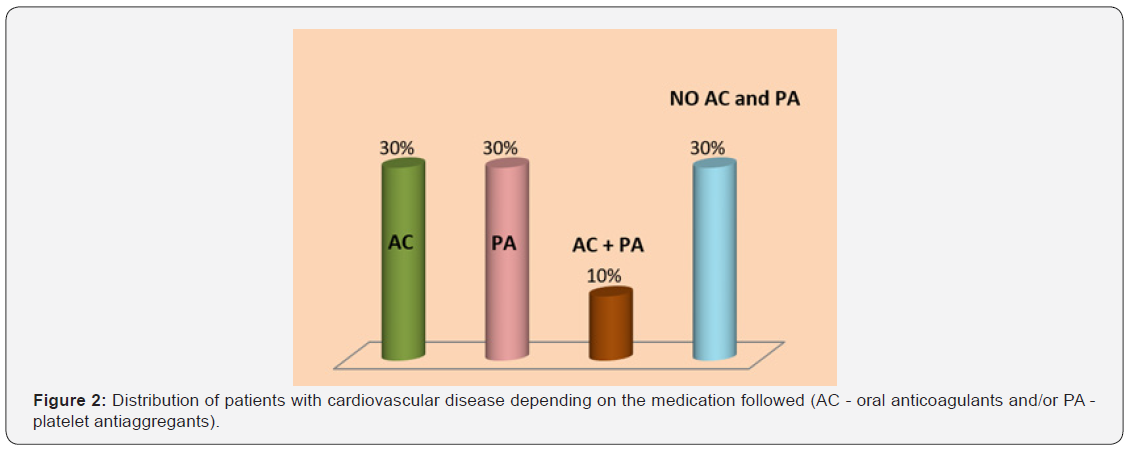

In Figure 2, 60% of patients with CVD were treated with AC (Acenocumarol or Apixaban) or PA (Acetylsalicylic acid, Clopidogrel or Ticagrelor) and 10% were administered drugs from both groups. This medication could be the explanation for the 85% of patients with CVD who experienced bleeding during periodontal examination.

Patients in this study presented different types of edentation according to the Kennedy classification. Most of the edentations were biterminal in both upper and lower jaws. Approximately 55% of the patients presented improper adaptation of prostheses on marginal profile, and 40% of them had no prosthetic crowns. Among patients with both PD and CVD, 45% had improper prostheses in terms of marginal closure, and the remaining 55% did not have prosthetic dentures. It is known that inappropriate prosthetic works are a local risk factor for PD, especially due to poor marginal adaptation that favors plaque retention on the prosthesis-tooth interface. Approximately 64% of patients with both CVD and PD had between 1 and 18 irrecoverable teeth that were either remnant roots or exhibited grade 2 or 3 dental mobility.

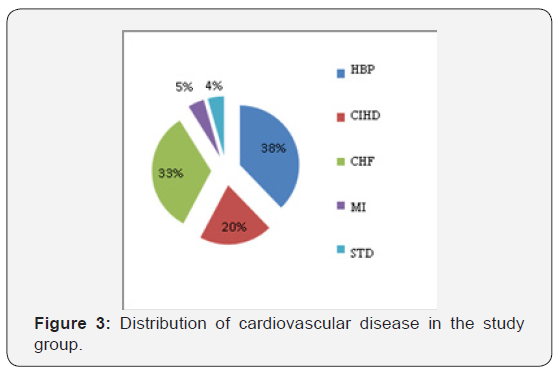

The CVDs diagnosed among the patients in this study included: HBP, CIHD, CHF, STD and MI (Figure 3). In patients with CVDs, the PD was found in 55% of patients with HBP, 40% in patients with CHF and 30% in patients with chronic CIHD.

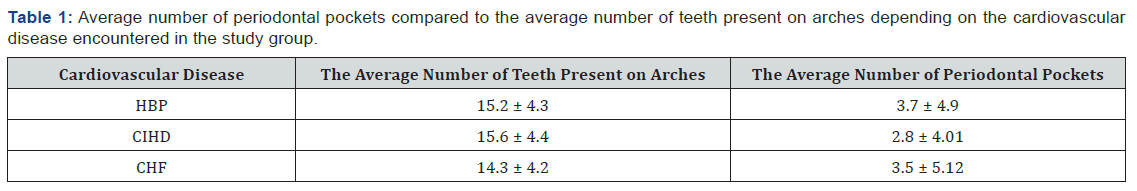

Among patients with CVD and PD, 73% had between 1 and 12 teeth with inactive periodontal pockets, most of them with a depth of 2 to 4mm. As seen in Table 1, the largest number of teeth with periodontal pockets compared with the total number of teeth has been found in patients with HBP.

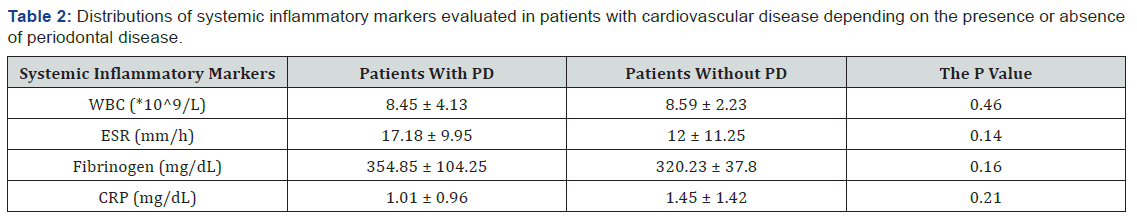

To evaluate the relationship between inflammatory markers and the presence of PD, the patients were divided into 2 groups. The first group included 11 patients with both CVD and PD, and the second group included 9 patients with CVD but without PD. There was no significant difference between the two groups regarding the inflammatory markers. However, as can be seen in Table 2, patients with both CVD and PD exhibited higher ESR and fibrinogen values compared with patients without PD.

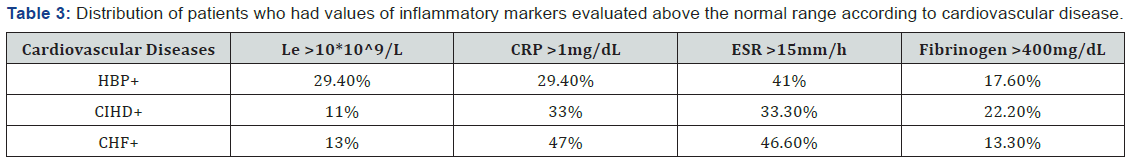

There was no clear evidence if inflammation manifested by leukocytosis was the cause or the effect of atherosclerosis. Among patients with HBP, approximately 30% had leukocytosis. In the Table 3 can be seen the distribution of patients who had values of inflammatory markers evaluated above the normal range according to cardiovascular disease.

Although a clear link between PD and CVDs has not been yet established, several studies focused on the analysis of the relationship between PD and HBP [5,23,24]. Numerous clinical and epidemiological studies reported that the leukocyte count is an independent risk factor for coronary heart disease. In our study, of patients with CIHD, only 11% had leukocytosis (Table 3). According to a study investigating the relationship between white blood cells counts and CIHD, increased leukocyte counts were associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in a group of undiagnosed patients. Leukocytosis influences the severity of coronary heart disease through multiple pathological mechanisms that mediate inflammation, causes the destruction of endothelial cells through oxidative stress and proteolysis, affects microcirculation by clogging the capillaries, arterioles and venules, induces hypercoagulability and contributes to the expansion of infarcted areas. Moreover, leukocytosis is a risk factor independent of atherosclerotic disease status [25]. Leukocytes play a pivotal role in normal host resistance at dental-plaque biofilm level and its dysfunctions are involved in periodontitis development [26].

Recently, numerous epidemiological studies confirmed that patients with elevated basal plasma levels of CRP have an increased risk of coronary artery disease and myocardial infarction. Prospective studies in the European and US countries have provided reliable data regarding the predictive value of CRP determinations on cardiovascular risk in both men and women. Thus, CRP is an indirect risk factor for coronary artery disease, and elevated levels may reflect some of the followings: inflammation of the coronary arteries in response to infectious agents; severity of inflammatory response in atherosclerotic vessels; extension of inflammation associated with myocardial ischemia; extension of inflammation associated with myocardial necrosis; the levels and activity of circulating proinflammatory cytokines.

There are two types of CRP tests: one of these has a measurable range that includes values obtained in patients with infectious or inflammatory processes (generally 0.3-20mg/dL) and the other can detect lower CRP levels (analytical sensitivity in around 0.01mg/dL) to estimate the risk of acute CVE. For this reason, the second test is termed CRP with high sensitivity (CRP ultrasensitive, “high-sensitive” CRP) [27]. At present, the value of the highly sensitive C-protein (hs-CRP) appears to be the most reliable predictor of acute CVE and is successfully used for the clinical assessment of patients with cardiovascular risk. Decision intervals for cardiovascular risk assessment are established according to the AHA: <0.1mg/dL - low risk; 0.1-0.3mg/dL - moderate risk; >0.3mg/dL - increased risk. For values higher than 1mg/dL, a non-cardiovascular cause should be considered.

Although there is clear evidence of the role of inflammation in coronary artery disease, the precise mechanism underlying the relationship between plasma CRP levels and the cardiovascular risk has not been yet established. It is still unclear whether increased CRP levels are the cause or the consequence of the disease or both. The inflammatory response associated with atheromatous lesions may trigger cytokine production in an amount sufficient to induce a measurable increase in plasma CRP. In turn, CRP, due to pro-inflammatory effects, may increase the formation of the dental plaque, or may have other effect that aggravate the PD.

In our study, 30% of the patients with CVD had CRP values ranging between 0.1 and 0.3mg/dL, which were associated with moderate cardiovascular risk. Among patients with chronic heart failure, 47% had CPR values higher than 1mg/dL. It has been reported that people with CRP serum levels that consistently exceed 1mg/dL had an increased risk of myocardial infarction. The following circumstances could influence the CRP values: pregnancy, obesity, the presence of an intrauterine contraceptive device, or the use of medications such as oral contraceptives, menopausal hormone replacement therapy, statins (drugs used to lower blood cholesterol), and anti-inflammatory drugs. The PD was present in 64% of rural patients and in 44% of urban patients. A recent transversal study based on the simple randomized method performed on 470 rural subjects, showed a 73.62% prevalence of PD [28]. These findings could be explained by the fact that the rural population neglects the oral health and is unaware of the seriousness of the oro-dental conditions, and also by the low accessibility to dental services.

Conclusion

Future studies should focus on a better understanding of the common pathogenic mechanisms and the interactions between cardiovascular disease and periodontal disease. In order to demonstrate the causal relationship between periodontal disease and cardiovascular disease, further studies should be performed on a large population to provide data enabling statistically significant correlations.

To Know More About Anatomy physiology & Biochemistry Journal Please click on: https://juniperpublishers.com/apbij/index.php