INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF PULMONARY & RESPIRATORY SCIENCES

Introduction

Bronchial Asthma is an airway disease with variable

degrees of bronchial mucosal inflammation and intermittent episodes of

airway obstruction and bronchial hyperesponsivness. That asthma is a

syndrome consisting of different phenotypes has been recognized for a

long time by clinicians [1]. New evidence indicates that the composition

of airway microbiota differs in states of health and disease. Different

chronic airway diseases had been related to changes in microbiota due

to various factors which could affect severity of symptoms and even

response to treatment [2]. Micro biome may be one of the protective

factors against asthma in early life [3].

What is Airway Microbiota

It a complex variety of microbes present intrachea

and different generations of the bronchi either on the mucus layer or

the epithelial surfaces or even both. These microbes include bacteria,

yeasts, viruses and bacteriophages. The bacterial part of microbiomeis

the most prevalent component with various genera: Prevotella,

Sphingomonas, Pseudomonas, Acinetobacter, Fusobacterium, Megasphaera,

Veillonella, Staphylococcus, and Streptococcus. The bronchial tree for

instance contains a mean of 2000 bacterial genomes per cm2 surface [4].

The mucosal surfaces in the human body are the home of 10-100 trillion

microbes with a diversity of greater than 1,000 species [5]. The highest

concentration of microbes is found in the GI tract, compared to those

found in the lower airways. Healthy human lungs are not sterile, as

previously believed, but it is unknown whether the microbes in the lungs

form a stable community or are a series of transient colonizers [6].

However, various theories about the origin of lower

airway microbiota in healthy individuals had been suggested. As it may

represent true colonization of the lower generations of bronchi, or it

is the result of turnover of the microbial community or it is just

contamination of oropharynx during lower airway

sampling or even linked potentially to those who are incorrectly

categorized as truly healthy [7].

Importance of microbiota

The commensal bacteria are nonpathogenic and defend our airways against the pathogens. There are several possible mechanisms:

- Commensals are the native competitors of pathogenic bacteria, because they occupy the same niche inside the human airways.

- They are able to produce antibacterial substances called bacteriocins which inhibit the growth of pathogens. Genera Bacillus, Lactobacillus, Lactococcus, Staphylococcus, Streptococcus, and Streptomyces are the main producers of bacteriocins in respiratory tract.

- Commensals are good inducers of anti allergic Th1 cascade with anti-inflammatory interleukin (IL)-10, FOXP3, and secretory immunoglobulin A (sIgA) production [7].

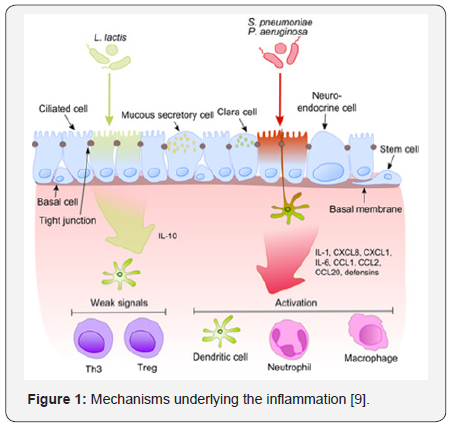

Airway epithelial cell and microbiota interaction

The airway epithelium together with alveolar

macrophages and dendritic cells collectively can recognize of bacterial

products trapped into the lower airways with the inhaled air. Some of

these products are can potentiate pro inflammatory stimuli. So it is a

challenging issue to distinguish between pathogens and commensals to

avoid development of constant or persistent inflammation and help to

develop tolerance against harmless microbiota [8].

Once pathogenic bacterium (e.g., S. pneumoniae,

P.aeruginosa) has been attached to activated pattern recognition

receptors located on/in bronchial epithelial cells, the proinflammatory

cytokines pathways are predominant via release of IL-1, IL-6 and IL-8

which induce neutrophils, dendritic cells and macrophages chemotaxis to

target cells (e.g., neutrophils, dendritic cells and macrophages.

Standard microbiota fail to induce strong signaling, thus aborting

inflammation. (Figure 1) [9].

This process becomes much more intriguing when taking into

account that commensals often share their surface molecules

with pathogens. Epithelial cells are equipped with very sensitive

recognition tools - toll like receptors (TLRs), NOD like receptors

(NLRs) and retinoic acid-inducible gene (RIG)-I-like receptors

(RLRs) which determine presence of non commensal bacteria

which activate cellular components of the adaptive and innate

immunity and recruit them to the infection site [7].

NF-κB is the principal regulators of different response to

harmful microbiota as it is become activated by a number of

stimuli as bacterial cell walls or inflammatory cytokines. This

results in its translocation from the cytoplasm into the nucleus to

activate epithelial cells pro-inflammatory genes. These specific

genes can recognize a particular nucleotide sequence (5’-GGG

ACT TTC T-3’) in upstream region of response genes. [10]. Inspite

of expressing express the same microbe-associated molecular

patterns (MAMPs), harmless bacteria fails to translocate NF-κB

into the nucleus thus preventing the inflammation. The balance

between pathogens and commensals is extremely important in

the maintenance of homeostasis in the respiratory tract [9].

Pediatric acterial airway microbiota in early life

A neonatal mouse exposed to a broad-spectrum antibiotic has

been shown to increase allergen-induced airway inflammation

susceptibility [4]. Germ-free mice also exhibit enhanced airway

inflammation upon allergen exposure [3], while colonizing

OF germ free mice with microbiota from conventional mice

decreased accumulation of natural killer T (NKT) cells in their

airways .This was only observed in neonates not in adult mice.

This highlights the importance of early life as a critical period for

intervention [11].

Absence of airway colonization during this critical

neonatal window resulted in sustained susceptibility to allergicinflammation through adulthood. This ensure long-term control

of allergic airway inflammation via controlling commensal

bacteria communities early in early life [12].

Microbiota and climax community

Climax community is defined as a microbial community that

has reached a final or “climax” steady state best adapted for

growth at that specific niche along the mucosa. However, this

climax community is dynamic and still exhibits both resistance

and resilience [13]. Evidence is now accumulating that longterm

dietary pressures , repeated antibiotic use, GI illnesses or

medications such as antacids, proton pump inhibitors, and nonsteroidal

anti-inflammatory drugs can break both the resistance

and resilience of a community and result in it re-assembling into

another climax community, although this may be accompanied

by detrimental changes in host mucosal immuno biology and

physiology. One mechanism underlying the activity of probiotic

microbes and prebiotic nutrients may be the ability to restructure

a climax community to improve host mucosal immuno biology

and physiology [14].

Microbiota (microflora) hypothesis

Several theories had been suggested to explain the increase

in the incidence of asthma and other allergic diseases over the

past 30 years and the discrepancy between the higher rates of

allergic disease among industrialized relative to developing

countries. One rising assumption is a lack of early microbial

stimulation which results in aberrant immune responses to

innocuous antigens later in life “hygiene hypothesis” [15].

Life style modifications and over use of broad spectrum

antibiotics raise the concept of disturbance of mechanisms of

mucosal immunologic tolerance due to changing diversity of

gastrointestinal (GI) microbiota composition in westernized

areas [16].

Epidemiologic and clinical data supporting this interpretation include

- a positive correlation between increasing risk for asthma/allergies and increasing use antibiotics in industrialized countries,

- Altered fecal microbiota composition had been correlated to different atopic diseases

- Oral probiotics orsignificant dietary changes lead to some successful prevention/reduction of severity of allergic diseases.

Experimental data in mice compared that immune response

generation and normal ones which showed numerous defects

in immune response [17]. Altogether, these experimental,

epidemiologic, and clinical observations support the hypothesis

that even minor changes in the quality or quantity of airway

microbiota can be one of the predisposing factors for allergic

disease [10].

Cross-talk between the gut and the lung

The existence of the gut–lung axis and its implications

for airway disease provide a portal for potential therapeutic

intervention in prevention or management of asthma [18].

Oral supplementation with probiotic strain of Bifidobacterium

and prebiotic non-digestible oligosaccharides reduced airway

IL6 and IL4 levels and protected against HDM-induced airway

inflammation. This suggest that some intestinal bacteria have

the capacity to suppress inflammation at a distal mucosal site

[19].

Oral tolerance and airway tolerance

Oral tolerance is defined as the propensity of ingested

antigens to abort subsequent systemic immune responses.

Gastrointestinal tract may be also involved in tolerance to inhaled

and ingested antigensvia CD4+ regulatory T cells (Tregs) that

produce immunosuppressive cytokines, IL-10 and TGFβ, in what

is termed “bystander suppression.” [19,20]. Mucosal signals,

such as those from the microbiota, keep resident dendritic cells

in an immature or non-inflammatory state [15].

Airway microbiata diversity in asthma

In asthmatic patients, certain airway microbial composition

was associated with airway eosinophilia and AHR to mannitol

but not airway neutrophilia. Comparing eosinophilic and

noneosinophilic asthmaas regards airway microbiome revealed

that Asthmatic patients with the lowest levels of eosinophils

had an altered bacterial microbial profile, with more Neisseria,

Bacteroides, and Rothia species and less Sphingomonas,

Halomonas, and Aeribacillus species compared with asthmatic

patients with high eosinophilia. This may invite furtherresearch

on effect of modulating diversity of microbiota to modulate

various asthma phenotypes [21].

Airway microbiota dysbiosis in asthma

Airway dysbiosis in patients with severe asthma appears to

differ from that observed in those with milder asthma. Specific

Bacterial communities as Proteobacteria were associated with

worsening ACQ scores and sputum total leukocyte values in

severe and poorly controlled asthma. Actinobacteria had been

associated with stable or even improving ACQ scores and can

predict steroid responsiveness [22].

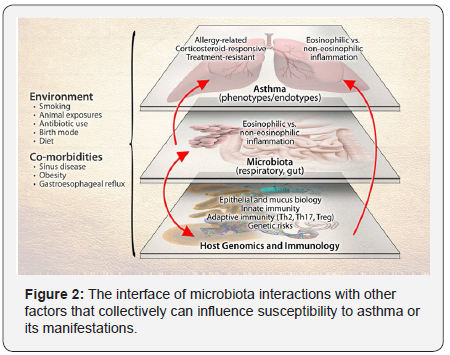

Airway microbiota and asthma heterogeneity

Dissecting the role of the microbiome in asthma is challenged

by the heterogeneity of the disease at multiple levels (Figure

2). These levels include asthma’s clinical and inflammatory

heterogeneity, genetic factors that contribute to asthma risk, and

the multiplicity of immune pathways involved in asthma. The

potential effects of environmental exposures on gene function,

immune responses, as well as microbiota composition add further

complexity. As with genetics, mechanistic consequences of the

altered microbiome may explain certain aspects or phenotypes

of asthma as the development of allergic or non-allergic asthma,and treatment-resistant asthma) [22] Components of the

depicted system-host genetics and immunology, microbiota,

environmental exposures, and the disease of asthma- are

themselves heterogeneous entities, presenting challenges to

more precisely dissect the role(s) of the microbiome in asthma.

Upper airway microbiota and asthma

Bisgaard et al. [23] demonstrated that the nasopharyngeal

microbiome composition was influenced by the early life

exposures, including attending day care, having siblings, and

taking antibiotics. Haemophilus, Streptococcus, Moraxella had

been previously associated with airway disease and increased

risk for asthma exacerbations. Early colonization with either

Moraxella, or Streptococcus was strongly associated with acute

lower respiratory viral infections. This colonization can be

predictor for asthma development later in life.

Thus, probiotic intervention studies of animals provide

encouraging evidence for intentional manipulation of the

intestinal microbiota as a strategy for asthma prevention and

management. A meta-analysis of a large number of randomized

trials of probiotic supplementation, on atopic sensitization

and asthma in children, however, shows that the success of

these interventions in mice does not translate easily to disease

prevention in humans. At a minimum, this highlights that

different probiotics may have distinct interactions with the host

microbiome and that some strains might be more specific for

modulating atopic inflammation but many other considerations,

such as diet, age of intervention, coincident environmental

exposures, length of supplementation period, and other as yet

unknown factors, are likely important [24].

Airway microbiota and severity of asthma

Relationships between the airway microbiome and disease

features have also been examined in patients with in severe

asthma. Different clinical phenotypes of severe asthma have

been described, suggesting the possible involvement of alternate

mechanistic pathways, as has been surmised for asthma in general. A preliminary analysis of the bronchial microbiome in

these subjects, poorly controlled despite high-dose ICS therapy,

noted significant relationships between different bacterial

community profiles and features such as body-mass index and

measures of asthma control [25]. A similar study of sputum

bacterial composition in 28 treatment-resistant asthmatics

found that the relative abundance of M. catarrhalis, Haemophilus,

or Streptococcus spp. correlated with worse lung function and

higher sputum neutrophil counts and IL-8 concentrations [19].

Microbiota and therapy of allergic disease

The composition of the microbiota can be manipulated by

combinations of antibiotics, probiotics, and dietary components

which may have direct growth promoting or inhibiting activity

for specific microbes. [26]. Certain types of fatty acids, phenolic

compounds, and carbohydrates may modulate these microbiota.

However, a single type of probiotic or dietary component will

not be efficacious in all individuals. This likely due to differences

in the types of microbial communities in different individuals.

The objective of the international Human Microbiome Project

is to characterize and define the human microbiome in states

of health and disease [10]. The challenge for future research is

to use this information to optimize probiotic/dietary therapy

to improve human health and prevent microbiota-associated

diseases, such as allergies .They are likely to include short chain

fatty acids and ionic polysaccharides [27] .

Microbiota and prevention of allergic disease

Probiotic intervention studies of animals provide

encouraging evidence for intentional manipulation of the

intestinal microbiota as a strategy for asthma prevention and

management. However, A large number of randomized trials on

the value of probiotic supplementation, on asthma incidence and

severity in children, could not show the same success of these

interventions as in mice [28-30]. This may be due to many other

considerations, such as diet, age of intervention, coincident

environmental exposures, length of supplementation period,

and other as yet unknown factors, are likely important [24,31-

34].

To Know More About International journal of pulmonary & Respiratory Sciences Please click on:

To Know More About Open Access Journals Please click on: ttps://juniperpublishers.com/index.php

No comments:

Post a Comment